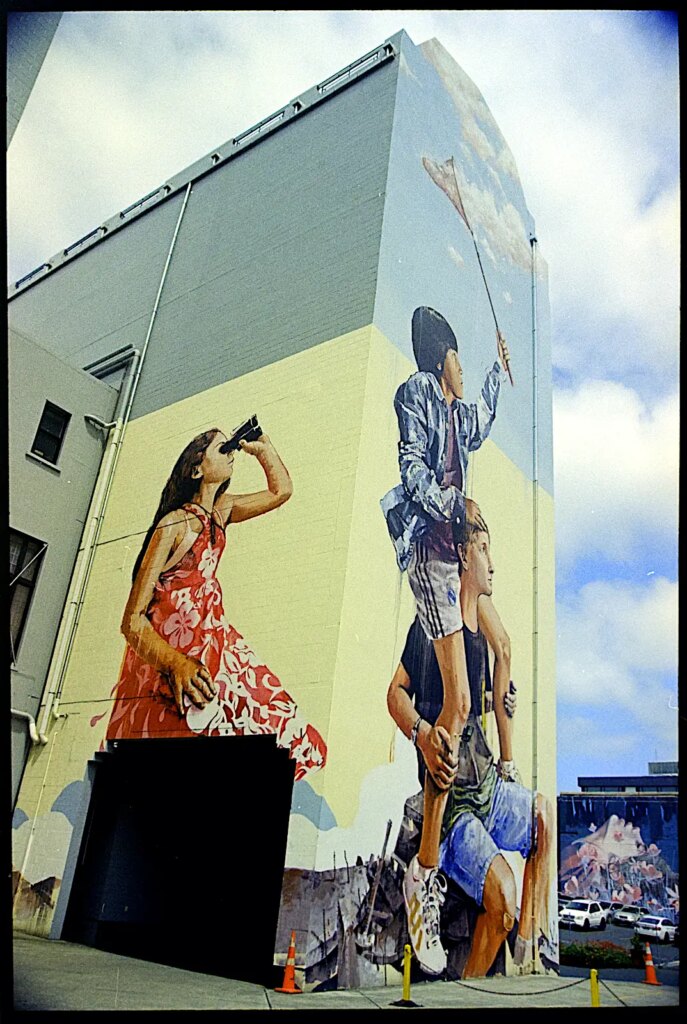

I recently had some disappointing results while trying out a colour negative film in a Retina IIc. I was shooting the urban art (and some graffiti) that has been created here in Dunedin, and some shots of the rhododendrons in the Botanic Gardens. Many of the frames are distinctly soft in places whilst others are bitingly sharp, despite careful focussing with a well adjusted, rangefinder camera.

Tests of lenses often warn about using smaller apertures because of the effects of diffraction, especially beyond f11 which seems to be the smallest recommended opening, with 35mm film and equivalent formats, at least. There is a trend with many modern camera lenses to design them to have ever larger maximum apertures, so much emphasis being placed on bokeh these days. Resolution will inevitably suffer at smaller apertures, both from diffraction but also to a degree because the optical design is optimised for the larger apertures.

So what causes diffraction?

When light passes through the iris opening in a lens, the rays close to the edge of the blades are ‘bent’ slightly, causing blurring. With a larger aperture this has little or no effect, the blurred area being only a small fraction of the overall image. With a small aperture, f/16 and smaller, the blurring affects a much larger proportion of the opening on most smaller format lenses.

If there is no important fine detail needing to be recorded, architectural subjects for example, small apertures can enhance the apparent sharpness overall. But where fine detail is important, this must be taken into account.

Using a Nikon F801 SLR I usually work in aperture priority auto, the camera’s shutter speed range (up to 1/8000) accommodating the brightest light at quite large apertures. As a result, I am able to keep my aperture settings to the optimum. My Retina in comparison only goes to 1/500, four stops slower. This top speed is probably a little slow with a camera of this age too, even though CLA’d, and so to be as close to the marked speed as possible I tend to use 1/250. The largest aperture I could use in similar conditions would be f/11 at 1/500, so at 1/250 I have to use f/16, exactly where diffraction can become a problem.

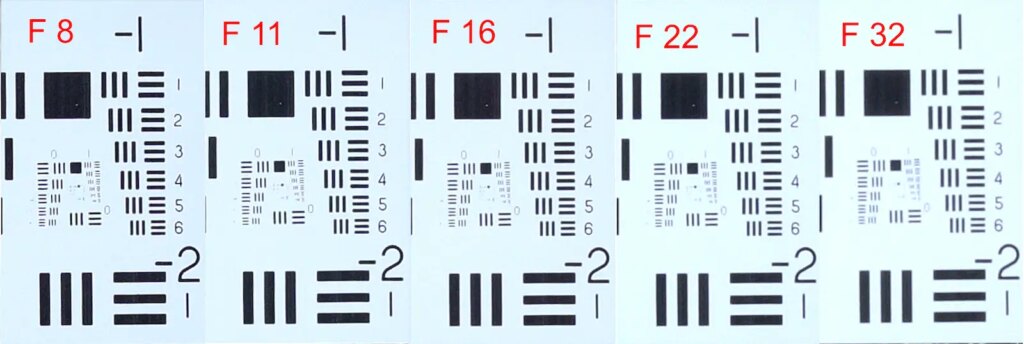

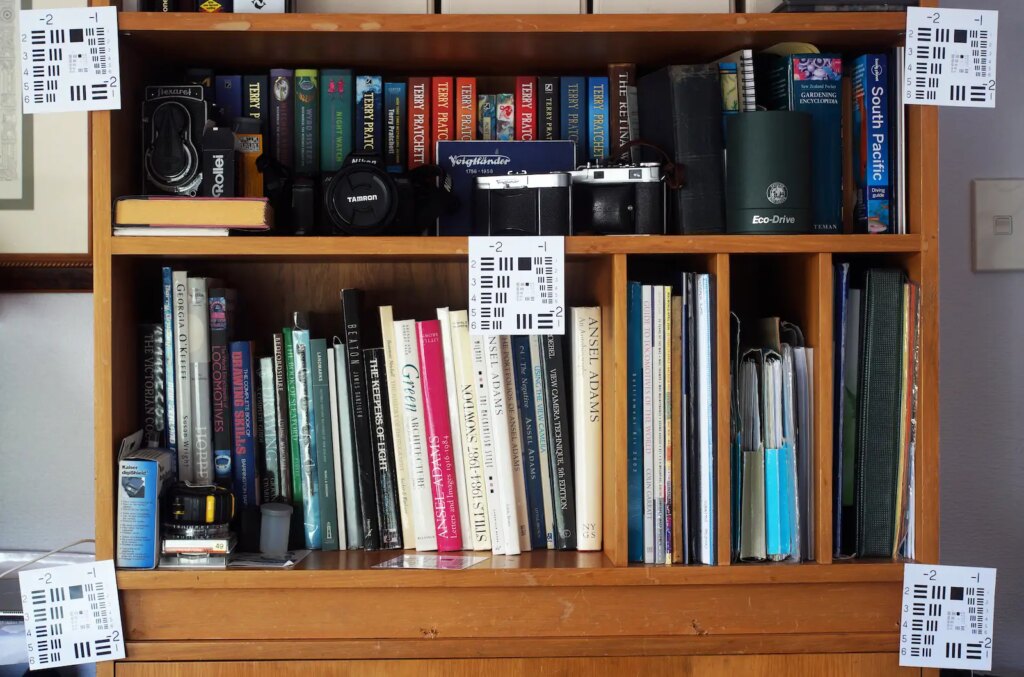

I tested this by shooting the set up shown at all the apertures on my 55mm Micro Nikkor. The fine spacings start to soften at f16 and are really soft by f32. The larger patterns aren’t too badly affected and could be sharpened in post whereas the finer ones couldn’t be brought back much at all. The composite is from screen shots of raw files in Affinity from the central target without any processing.

Whilst aperture has most effect, lens design may also have a part to play, especially in my case. The Xenon lens on the IIc is the same 6-element design as the f2 of the Retina IIIc but with a reduced maximum aperture of f2.8. Having been designed as an f2 lens, it may be computed to favour better resolution at the larger apertures, a feature of such lenses. After all, there is no point in paying a higher price for a fast lens if it doesn’t perform well at the largest apertures.

And finally, the film grain will impose a limit on detail resolution, in turn affected by contrast in the image.

All things to bear in mind when approaching your subject.

This is particularly applicable to smaller formats where shorter focal lengths are used and higher magnification of the image. Diffraction, and grain too, is less of a problem as the camera format size increases. Medium and large formats suffer less from these effects, their lenses and aperture openings being physically larger than 35mm or smaller digital formats and results needing less enlargement. So if you are working in fields requiring the finest detail, size really does matter. For most of us, though, simply matching aperture choice to subject will suffice. And, of course, with digital, focus stacking is always an option for static subjects such as record or landscape when any aperture can be used but maximum sharpness and depth of field retained.

With a camera like the Retina or any camera/lens with small iris openings, using slower emulsions and possibly neutral density filters are essential for some subjects to avoid stopping down too far. Extended depth of field looks to be ruled out in some cases too. All part of the challenge I guess.

(Digitised copies of negatives are produced with a Sony A3000 with an AI’d 55mm Micro Nikkor and adapters processed in Affinity Photo.)

Share this post:

Comments

Nikojorj on Diffraction and its Impact on Sharpness – By Tony Warren

Comment posted: 01/03/2023

Note that in digital, some sharpening is often enough to mitigate most of the effects of diffraction.

Comment posted: 01/03/2023

Ken Rowin on Diffraction and its Impact on Sharpness – By Tony Warren

Comment posted: 01/03/2023

Thanks again.

Comment posted: 01/03/2023

Davcid Hill on Diffraction and its Impact on Sharpness – By Tony Warren

Comment posted: 01/03/2023

Comment posted: 01/03/2023

Gil Aegerter on Diffraction and its Impact on Sharpness – By Tony Warren

Comment posted: 01/03/2023

Comment posted: 01/03/2023

Comment posted: 01/03/2023

Ibraar Hussain on Diffraction and its Impact on Sharpness – By Tony Warren

Comment posted: 01/03/2023

And the chart comparing the levels of diffraction for given F stops is excellent!

I once read an article by ken Rockwell about this and since then I haven’t shot anything smaller than f11 that’s when I want max dof but often enough f8 is sharper and does the job.

Wouter Willemse on Diffraction and its Impact on Sharpness – By Tony Warren

Comment posted: 02/03/2023

On my DSLR, I avoid going beyond f/8 and try to keep f/5.6 as the go-to aperture; on my film cameras (including a well working rangefinder with bitingly sharp Voigtlander Ultron 35mm) I do frequently use f/11.

Since I never really felt that "having everything sharp" helped images look any nicer, f/16 was never the place to be for me. But for macro work, diffraction can really get in the way.

Ultimately, as nice as it is to get everything technically as good as possible, the first thing is always getting the image right - the composition and desired look of the result comes first. Even if that means using a less-desirable aperture.

Comment posted: 02/03/2023

Tony Warren on Diffraction and its Impact on Sharpness – By Tony Warren

Comment posted: 03/03/2023