Our senses are heightened when we travel. Everything is new—the mist enveloping the mountains, the cow meandering among the cars, the woman in the striking dress—and we want to save every moment. So we take out the camera and read the scene like a lion on the hunt, looking at light and shadow, textures and angles, shapes and colors. And by doing so we have decided, whether by conscious choice or not, to risk the enjoyment of the moment now for a snapshot that will last forever.

But this, I have found, is the antithesis of travel. The traveler’s job is to enjoy the destination, to engage with what’s in front of them, to understand and learn from a people different than them. I want to embrace the place with my full attention, not with a mind busy calculating a scene. But photography requires the opposite modus operandi. First, composing a picture encourages abstraction. We push unusable elements out of the frame, and avoid unnecessary details. We abstract away the world into blobs. Second, exposing a picture encourages calculation. We turn mechanical, engaging our mental energy into making sure that our subject is in focus, that the three variables of exposure are properly set to produce the desired effect. This mindset, when repeated at every new moment (of which there are many in travel), hinders our ability to travel well.

The drastic solution, of course, is to not bring the camera. But I’ve discovered a different way: engage the world through other means.

The Artist Mindset

The camera is a rather blunt instrument. With the press of a button the entire scene is captured and finalized, imprinted into the film or sensor. The pencil, however, is an instrument of infinite precision. A sketch artist must pay attention to every detail, decide upon an interpretation of every point, and employ all skill and effort into every movement of the hand.

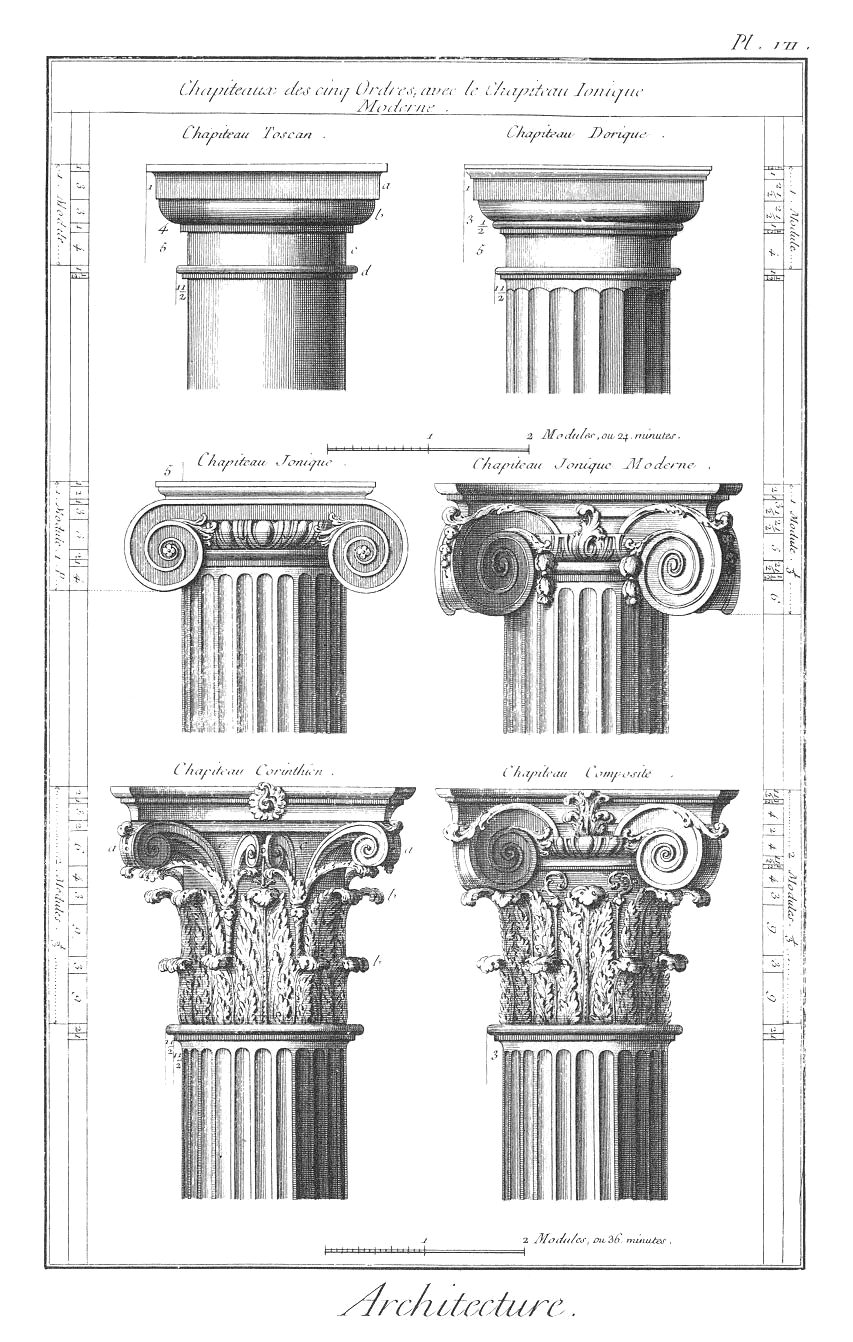

This precise form of observation, I have found, is a powerful antidote to my camera-wielding mindset. My wife and I had spent a hot day walking around the ancient agora in Athens. Tired and frankly done with old rocks, we hid in the shade in front of the Temple of Hephaestus. I took my notebook and decided that I would try to draw the damn temple. I started with a couple of lines, outlining the the overall shape of the temple. Then I had to count the number of columns making the facade, then the number of visible fluting on each column. Then there was the problem of figuring out the shaft and entasis, and the roof and its detailed frieze. Not to mention the steps leading to the temple, the adjacent facades, the rocks and bushes and trees.

It was a bad drawing, and I may have missed a column or two, but I did learn patience. I didn’t have the instant gratification of a camera. If I wanted a temple, I had to draw a temple. It was this embarrassing, painstaking labor that forced me to really know my subject, to see details that I would have ignored with a camera, to sit still and enjoy the place for what it is, not for the photograph I can get out of it.

The Writer Mindset

Another remedy is to write. We went to the Italian town of Vernazza for our honeymoon. The locals would come out of hiding at night, when the cruise ship crowds had dissipated. The streets and patios would be filled with beautiful people talking and laughing, drinking wine and smoking cigarettes. But there was one young man, no older than nineteen, that I would find every night walking the town in circles, back and forth, from the cliffs through the alleyways towards the cove, again and again, wearing the same scratchy sweater, sweating in the warm Italian night. His shoulders drooped, but he walked quickly and with meaning, as if he was in a hurry to go somewhere. His face spoke of sadness, of longing, of unrequited love.

I wanted to talk to him, to ask him what was burning through his mind during those long walks. But how could I interrupt that overwhelming sadness? So I picked up a pen and wrote a story. About a man with a long face that paced the town every night, spiraling deeper and deeper into darkness. It was my way of capturing that moment, of getting to know this young man. A photograph would not have done him justice. It would not have told the story.

Unlike a photograph, which represents a fixed point in time, a story flows through time. I realized that I could take a character—the rambunctious family next door, the old widow crossing the plaza, the restless young man—and peer into their future. I could turn my protagonist into a hero or into despair. I wasn’t writing for some audience—I wrote for me. If drawing is observation at its most precise form, then writing is communication at its most precise form. Writing brings your ideas out to battle on paper. It sharpens them. It brings clarity to muddy thoughts. And most importantly for me as a traveler, writing brings me closer to my subjects in a way that photography cannot.

Simplifying the camera

My parents shot film but I came-of-age in the midst of the digital revolution. It was all about megapixels, sensor size, maximum ISO, post-processing, pixel-peeping. But the more I travelled, the more I realized that I needed to minimize the amount of time spent in the photographer mindset. I needed to get out of the mire. It was then that I discovered film photography. So I picked up an Olympus Stylus Epic and focused on the basics. Composition, lighting, subject.

The plastic Olympus has a good lens, it’s portable, and it gets out of the way. The only thing I can do with it is compose and shoot. As Hamish points out, the lure of the uncomplicated camera is that it provides “clarity of function.” I’m no longer fiddling around with settings, retaking the same shot over and over, staring at the back of an LCD screen making sure everything was perfect. When I see something compelling I compose, press the shutter, and move on. I only have to turn on my photographer’s mindset for a moment, and I can instantly be a traveler again. I can quickly re-engage with the world. And when I find myself too-focused on the camera, I take out some paper and a pencil. And I draw, or write. Because as much as I love travel photography, I’ve found that travel is even better.

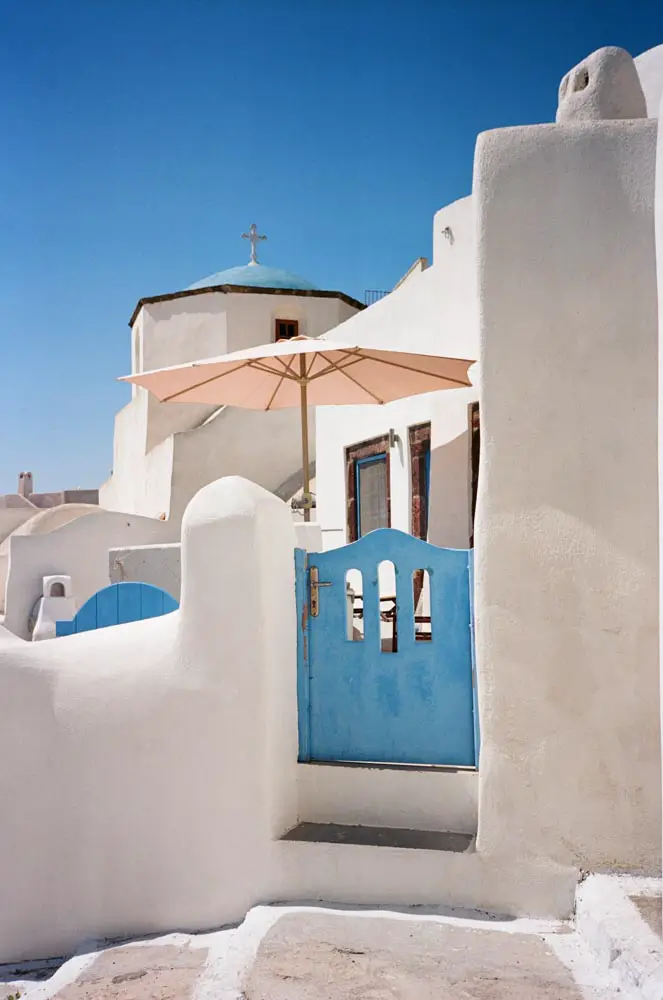

All photos shot on the Olympus Stylus Epic:

Share this post:

Comments

Ryan on How to Travel Without a Camera – By Elben Shira

Comment posted: 01/08/2018

I first thought I'd buy a Fuji XE3 but then I'd be taking thousands of pics instead of just enjoying the actual travel. Perhaps I'll just stick to my F100, a 35mm lens and a handful of Portra 400 so that I can better enjoy the trip rather than obscess over silly details that would detract from the experience.

Thanks for posting this, it's quite well written and may just help me enjoy my honeymoon even more!

Comment posted: 01/08/2018

Derek on How to Travel Without a Camera – By Elben Shira

Comment posted: 01/08/2018

Dominique Pierre-Nina on How to Travel Without a Camera – By Elben Shira

Comment posted: 02/08/2018

Thanks,

Dominique.

Comment posted: 02/08/2018

Marco Andres on How to Travel Without a Camera – By Elben Shira

Comment posted: 02/08/2018

It’s even worse when pixel peeking, or peeking and then selfishly dragging a companion out of their moment to look at the screen or even worse asking them to strike a pose.

And then move on to the next documented position. It’s difficult to photograph a famous place without being banal. Consider going where the locals go and photographing there…The trip isn’t about the camera equipment. Or pack lightly with one light camera and one prime, avoiding the tyranny of choice.

Shoot don’t spray. Set and forget (fix the ISO) and preset the focus. . It’s not high art. Or for a travel spread/website/…it’s meant for friends.

Observe. Experience the place.

Dan Castelli on How to Travel Without a Camera – By Elben Shira

Comment posted: 02/08/2018

Well, you're correct. But, I would like to offer the following: A good photographer should try and impose order out of a chaotic scene. We do this by lens selection, by our position relative to the subject, etc. The best photos are the ones that have stripped away everything in the scene that does not contribute to the subject. We do that on the scene, or in a darkroom or on a computer monitor. An artist has the luxury of editing in real time, drawing only what they want. I know from personal experience: our daughter is a professionally trained artist. This is how she makes a living. She just returned from Ireland with a sketchbook full of great drawings (well, I AM her father.) My wife & I will be going to Ireland in about 8 weeks and I'll be packing my rangefinder and a28mm lens & HP-5. When we return, daughter & father will combine images into a book. It'll be fun to see identical scenes through the eyes of artist and photographer.

On another point, I carry a journal that I make notes as I go along. I've always done this; it never occurred to me not to take notes. The weather, street smells, camera settings...my wife is like an archivist: she save every piece of paper that we accumulate on our travels, newspapers, receipts, food labels & whatever. She makes wonderful scrapbooks. It's funny but I just always thought this is how you should travel, immerse yourself in the place.

I enjoyed your article and your photos. Hope to hear more from you.

Mike Gayler on How to Travel Without a Camera – By Elben Shira

Comment posted: 02/08/2018

I have come late to photography - and still consider myself a snapper, not a photographer. However, I've been sketching (mainly pen & ink, sometimes in watercolour) for many years and have built up a number of journals covering the years while my children were growing up, and they, as adults, still look at them and say "I remember that holiday". All the digital photos are lost.

Sketching and photography are very different disciplines. Sketching requires you (me) to slow down to a glacial pace, and really observe things about places that you'd miss in the blink of an eye, or the click of a shutter. You might notice them later in the photo you've made, but you will have lost that connection in time and place.

Photography on the other hand allows you to capture fleeting moments, to capture the things that you (I) can't draw - people for example, and to get that colour just as the light changes, or to hold in a moment the shadows of evening on a beach, or to see forever one of your grandchildren on that day when they are between child and adult.

Both sketch artists and photographers obsess about their gear - the right paper, the right ink, the right brush; or the right film, the right lens, or the right camera - but it's the hand holding the brush or the camera, and the skill in moving from eye to object that we all strive for.

Neil on How to Travel Without a Camera – By Elben Shira

Comment posted: 02/08/2018

Tobias Eriksson on How to Travel Without a Camera – By Elben Shira

Comment posted: 02/08/2018

I do have some comments, though. One is: There are different ways of photographing. There is of course the cliché tourist-through-the-lens-watch-when-back-home phenomenon. I would argue that many (amateur) photographers make their photographs by "immersion". That is - staying in a 'scene'/site long enough to capture its essence from her/his point of view. That's the way of the conscious photographer who knows that photography is both placing the subject in the viewfinder but also placing yourself in the scene to make a good photograph. Eduardo Pavez Goye is an inspiration in this sense - watch his videos!

Since I am also a keen (but not prolific) sketch artist myself I definitely see your point in this article. And I strongly support your approach(es) to traveling. However in the light of things not having to be mentioned so obvious they are we must limit our air travel to near zero, these ways of immersion (drawing, writing, photographing) are important if we're to not be mere tourists but experience new places in a more mindful way.

I wish to conclude with recommending the books of sketch artist Danny Gregory - particularly The Creative License and Everyday Matters a Memoir.

Dave on How to Travel Without a Camera – By Elben Shira

Comment posted: 04/08/2018

Comment posted: 04/08/2018