In the great British tradition of “Keep calm and muddle through”, during WW2, British official war photographers had used a whole hodge podge of assorted cameras, ranging from large format 5″ x 4″ plate cameras from Houghton Butcher in the UK and Graflex in the USA down to 35mm cameras from Leica, Contax, Kodak and others.

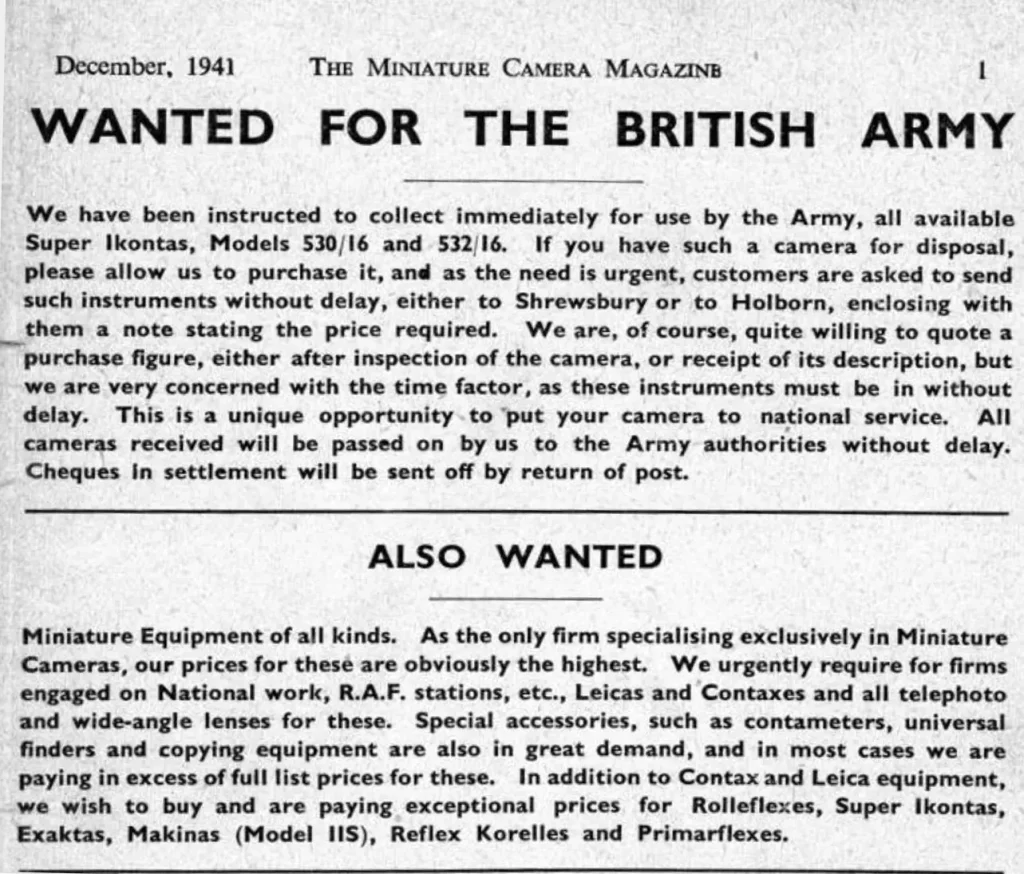

The preferred format at the beginning of the war was probably 120 film, seen as a reasonable compromise between the plate cameras, with their impracticability in a modern fast moving fluid war and the 35mm, whose negative size and quality was seen to be a limitation. There was such a shortage of cameras that an appeal was put out to UK photographers asking them to sell their cameras to the UK military: See an example of such an advert here:

At the end of the war, Leica was in the British control zone of Germany. The UK intelligence services sent a team to Leica in 1946, to investigate their products, with a view to specifying a standard camera for the UK military. Wartime development of film technology, had now made 35mm a practical proposition to use as a standard negative size, with a good compromise between film speed and grain.

As a result of the London Agreement of 1945/46, all German patents were ruled to be invalid and open for free copy. The intelligence service left Leica with a complete set of microfilm plans for the pre-war IIIB and post war IIIC. These cameras are functionally identical but the IIIC is slightly larger, uses some more readily available raw materials and simplified production methods.

The contract to produce the camera for the UK military was awarded to Reid and Sigrist, one of the UK’s top precision aircraft instrument makers. The UK’s own camera industry was not seen as being capable of making the cameras to the required standards. Ilford for example also used an instrument maker, Peto Scott, to make their Leica competitor, the Witness.

Reid and Sigrist converted all the metric measurements into imperial, other than the 39mm lens mount (albeit even Leica use imperial for the thread pitch at 26 tpi). Presumably this is because all Reid’s machine tools were graduated in imperial. Reid decided that they would make their version of the pre-war IIIB, as they felt with its better materials and production methods, this would result in a more reliable and robust camera for use in a military environment.

They also took the opportunity to improve the tolerances, fit and finish to the standards they were used to from aircraft instruments and gyroscopes. The end result is the best built and finished of all LTM type cameras. They were not cheap. For example in 1954, a Reid and Sigrist model 3 with the standard and very good Taylor, Taylor and Hobson collapsible 2 inch f2 lens was £145, equivalent to £3500 in today’s money.

They were slightly more expensive than a Leica IIIF with a collapsible Summicron, which including import duty, was £135. Total production of the Reid model 3 was around 1600 civilian models and 700 military. They also made a model 2 with no slow speeds and a model 1 with no rangefinder but these are even rarer than the model 3. If you compare this with Leica, who made well over half a million of their LTM cameras, you can see why the Reid and Sigrist are rare and sought after.

Why were so few Reids sold? A number of reasons. They were slightly more expensive than the equivalent Leica. Leica was German and had 20+ years reputation of making very fine cameras, so erroneously it was perceived to be better than the Reid. R&S took a long time to get into proper production and the civilian model cameras mainly arrived after the military order was fulfilled. Therefore by the time the improved Model III Type 2 was available, the Leica M3 with bayonet mounted lenses, lever wind and most importantly, a vastly better combined viewfinder and rangefinder, had arrived.

Share this post:

Comments

Terry B on A brief history of Reid & Sigrist – Guest post by Wilson Laidlaw

Comment posted: 01/10/2016

This is the one missed camera purchase opportunity that still haunts me to this day so, thank you Wilson for opening the wound. :D)

For anyone wishing to know more about this fascinating camera and company, try this link:

http://www.l39sm.co.uk/about_reid.php

Comment posted: 01/10/2016

Kevin on A brief history of Reid & Sigrist – Guest post by Wilson Laidlaw

Comment posted: 01/10/2016

jeremy north on A brief history of Reid & Sigrist – Guest post by Wilson Laidlaw

Comment posted: 02/10/2016

Comment posted: 02/10/2016

Benjamin on A brief history of Reid & Sigrist – Guest post by Wilson Laidlaw

Comment posted: 03/10/2016

Bravo pour ce blog, réellement passionnant et enthousiasmant.

Benjamin, from south of France.

Wilson Laidlaw on A brief history of Reid & Sigrist – Guest post by Wilson Laidlaw

Comment posted: 03/10/2016

It has a very nice feature on the shutter release, in that it has a shutter cocked indicator, which appears in one of the windows on the shutter button shroud. A standard Leica LTM cable or delayed release will fit inside the shroud, so it does not have to be removed (and lost!) like the Leica one does, to fit a cable or delayed release. In fact it does not remove at all.

I have been very busy lately, so just coming to the end of the first roll now and will send for processing. I don't process myself anymore, due to many years of not bothering with gloves or proper ventilation and sensitising myself to most photo chemicals - be warned. I am not using the lens I expect to be using mostly on this camera, a 1999 Leica Special Edition Chrome Type V 50mm Summicron f2 LTM, which is currently being pushed through Heathrow customs by an arthritic snail with a Zimmer frame. I am using a Canon 5cm f1.9, which is not a bad lens but has very noticeable spherical aberration in the corners from f2.8 wider and also has quite cool rendering, when used for colour (on my Leica SL). Probably a 1B Skylight filter would do no harm but finding one with 40.5mm x 0.5mm pitch thread is easier said than done. When I go through the mountain of post waiting for me, I should find a new wind on knob to replace the one with damaged chrome.

Comment posted: 03/10/2016

Wilson Laidlaw on A brief history of Reid & Sigrist – Guest post by Wilson Laidlaw

Comment posted: 04/10/2016

Wilson

Comment posted: 04/10/2016

George Appletre on A brief history of Reid & Sigrist – Guest post by Wilson Laidlaw

Comment posted: 04/10/2016

Comment posted: 04/10/2016

Comment posted: 04/10/2016

Wilson Laidlaw on A brief history of Reid & Sigrist – Guest post by Wilson Laidlaw

Comment posted: 06/10/2016

Comment posted: 06/10/2016

Comment posted: 06/10/2016

Comment posted: 06/10/2016

Comment posted: 06/10/2016

Comment posted: 06/10/2016

George Appletre on A brief history of Reid & Sigrist – Guest post by Wilson Laidlaw

Comment posted: 07/10/2016

Wilson Laidlaw on A brief history of Reid & Sigrist – Guest post by Wilson Laidlaw

Comment posted: 08/10/2016

Whether Leica specifies the specific characteristics of the glass they want in their blanks from Schott or picks glass from no doubt the wide range that Schott offer, I doubt if we will ever find out, as I would guess it is a deadly trade secret. When Leica design a new lens, it would very much be a chicken and egg situation, do they design the best lens they can and then tell Zeiss what they need in the way of refractive indices and for some elements, anomalous dispersion or start the design knowing what characteristics of glass Zeiss can offer "off the shelf".

Wilson

Wilson Laidlaw on A brief history of Reid & Sigrist – Guest post by Wilson Laidlaw

Comment posted: 08/10/2016