Film photography is often regarded as more difficult than digital. A large percentage of this likely comes down to the lack of the ability to check results in those first seconds after the button has been pressed. The result of this is that it’s harder to diagnose problems, especially problems with exposure, specifically if you’re unsure of what poor exposure looks like in the end results.

The interesting thing about negative film photography is that poor exposure doesn’t always result in a poor outcome. In fact, with some films, a touch of overexposure not only doesn’t do any harm, but it can actually help ensure good results.

It is from this fact that the oft-repeated mantras of “expose for the shadows”, “shoot half box speed” and “err on the side of overexposure” come from – all of these mantras point toward some degree of over exposure!

There is good reason for this too, it is in fact underexposure that is the main cause of slightly shitty looking murky results. Aiming for some degree of overexposure is a great way to avoid that problem – especially when you’re new to film photography.

But to what degree is over exposure of negative film ok? Well, the answer to that question is as deep as it is long, and as such is way beyond my desire (or knowledge) to cover in its entirety. What I do want to talk about is my personal experiences of overexposure of film, how I’ve used that experience to completely remove the problem of accidental underexposure and murky unattractive photos. Finally, I also want to make the point that I made it so easy for myself that it felt like cheating. So much so that I am now purposefully making it harder for myself – which ain’t a bad problem to have!

Before I get into this, let me just point out that this article assumes you are shooting film and either digitally scanning your negatives or having them scanned by a lab. This is what I do, and it is within the scope of that practice that I am writing.

I also want to emphasise the point that this isn’t a post about best practice – this is a post about what many photographers would consider cheating. “Perfect” exposure will always result in the best results. This is more about getting closer to the best results without necessarily being a technically perfect photographer. It is also worth noting that this doesn’t work with all film. The films I talk about within, it does; beyond that, it’s up to you to experiment…

My perfectly exposed (looking) photos

First I want to share two interesting facts about my negative film photography. The first is that in the last year I have used a light meter less than I have before. The second is that in the last year I have taken fewer accidentally underexposed film photos than I have ever before – in fact 9 rolls out of 10 I don’t get a single murky underexposed frame on a roll at all, and when I do, it’s not unexpected.

As an example, I recently went out taking photos with a friend. He’s a good photographer, he knows what he’s doing and was shooting with his super-duper-top-flight-Canon autoexposure film camera. I had my Leica M-A, a meterless manual camera. Every single one of my photos came out perfectly, whereas at least a couple of his results were murky from underexposure. So what? I’m saying I’m a better judge of light than a very expensive camera, right? No, not at all! What I’m actually saying is that at that point in time I was just a bit better at cheating with my Leica M-A than my mate was with his fancy-pants Canon.

The reality is, if you looked at my mates negatives alone you would judge him a much better photographer than me. All 36 of his frames would have been fairly consistent in their density. That is to say that if you held the negatives up to the light they would look evenly exposed across the roll. Yes he suffered a couple of thin, slightly underexposed negatives that resulted in a murky scan. But this was likely because the light he was photographing tricked the meter of his camera into slightly overestimating the amount of light. But that was just a couple of frames. Overall, his negatives would have been pretty accurately exposed, and more importantly – even taking into account the couple of slightly under shots – they would have been fairly evenly exposed across the extent of the film.

My negatives on the other hand varied wildly in their density. Some were quite close to accurately exposed, but many were massively overexposed, very dense, thick, dark negatives. There’s very good reason for this too. Whilst he was changing his settings on a shot by shot basis, I hardly ever changed my settings with regard to the light. In fact, almost regardless of light, indoors, in shade or outside I just shot my camera at pretty much the settings I fancied, only taking the minimum of care. Yet despite this, the outcome was that the scanned negatives look pretty damn good. They look like they were all exposed accurately, when actually the exposure varied a great deal.

The reason for this is quite simple. Firstly the huge overexposure latitude of the film I chose to shoot gave me massive room for error. Secondly, I know that any “mistakes” I make in exposure will be compensated for when the film is scanned. And thirdly, through experimentation, I now have the experience and understanding of the length, breadth and width of the room for error the combination of latitude and mistake-compensation the scanner gives me to know what I can get away with in what light. Let me explain…

Choice of film

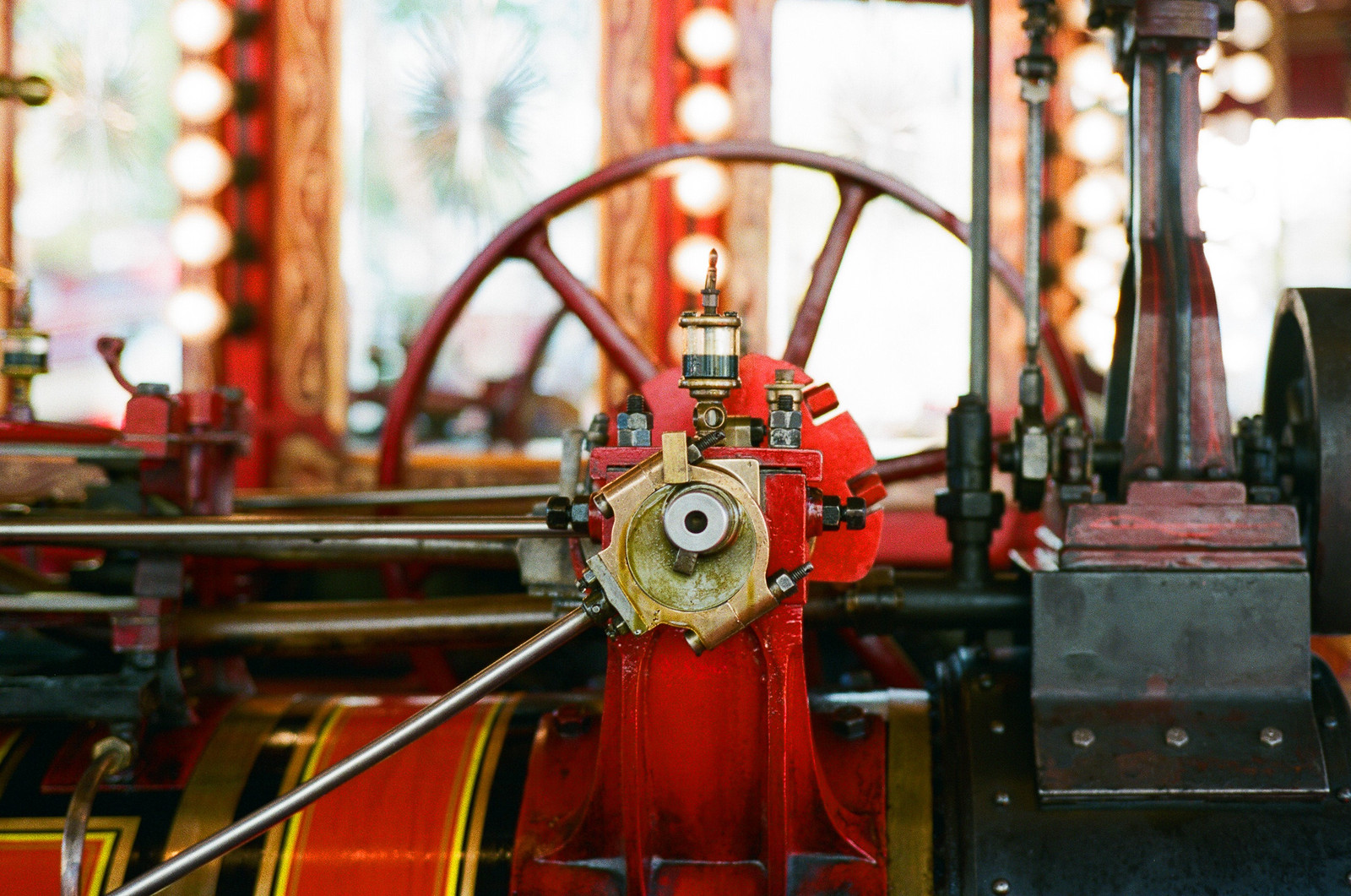

The films I choose to shoot are Portra 400 and Ilford HP5+. I shoot these films primarily because I like the look of the results. Additionally to this though, I shoot them because they’re incredibly forgiving. Portra 400 is especially impressive as not only does it allow lots of overexposure, it does it without introducing too much in the way of undesirable changes in colours. It’s no exaggeration to say that I have had useable photos shooting Portra 400 overexposed by what I’d guess was about 9 stops. This photo was shot at f/1.5 at 1/60th of a second in bright sunlight (I know it’s not perfect, but I’ll come to that in a mo).

Overexposure latitude – it’s not a myth!

I’d been told this sort of overexposure was ok with Portra 400 a few times, but it wasn’t until I tried it for myself that I really believed it. It just doesn’t seem to make sense that it would be possible to overexpose to this sort of degree and still get a perfectly usable photo. If you tried this with a digital camera the out of camera shot would be white. You might – if you shot RAW with a really fancy modern digital camera – be able to pull something back, but I’d bet it wouldn’t be much good.

Yet with the likes of Portra 400 this is abundantly possible. The reasons for this are its very broad overexposure latitude and the simple way negative film works. In very much layman’s terms (because that’s about the most of it I understand) the more light that hits the negative – albeit to an ever decreasing degree – the more chemical reaction occurs in the film’s emulsion. The more the chemical reaction occurs the thicker, or more dense, the negative gets. Hold a developed overexposed negative up to the light and it will look darker than a normally exposed one. The darker the negative the more the chemicals have reacted to the light. Inversely, very underexposed developed negatives will have areas which are completely clear. Where the negative is clear, no chemical reaction has occurred.

The importance of avoiding underexposure

This is of course why it’s so important to avoid underexposure, and ultimately the basis of where all the aforementioned mantras come from. In an underexposed negative there is less or indeed no chemical reaction, and where there is no chemical reaction there is no picture to scan.

Density correction in the scan

The next step is extracting that picture from the negative. Negative film is, of course, negative, so where the negative is highly exposed it is dark, but the end result of that part of the photo will be light once it has been inverted into a positive image. With films with as broad a latitude as Portra 400, to get a positive photo out of a highly exposed, very dark or dense negative you simply need to shine a brighter light through it. The more dense, the brighter the light required.

With Portra 400, it almost doesn’t matter how overexposed or dense the negative is, it is still theoretically possible to obtain a potentially usable image. Taking image quality concerns out of the equation for a second, it’s quite safe to say that as long as the chemical reaction has happened, there will be a picture on the negative. Inversely of course – as mentioned – where there is no chemical reaction there is no picture. You can’t shine less light through something that’s completely clear and expect to see a picture if there’s no picture to be seen.

This variation in brightness of light is what happens when my massively varied negatives go through a scanner. The really thick dense overexposed photos get a bright light shone through them, and the “better” exposed ones get a less bright light shone through them. This process is called density correction and is what results in all of my wildly differently exposed negatives all looking evenly exposed in the final scanned images.

Understanding of the room for manoeuvre

What’s important in this process is having a good idea of the scale of the room for error. The size of the room for error is – at least for the sake of this post – determined by the exposure latitude of the film and the capability and quality of the scanner used to scan the negatives. As mentioned I use Portra 400 film. Alongside the use of this film I use a commercial Noritsu scanner. Up until recently I was outsourcing my scanning, though since I’ve just bought a Noritsu of my own, I shall soon be scanning my own negatives. That said, regardless of by whom and where my negatives are scanned, through experimentation I have found the limitations of the scanner and film.

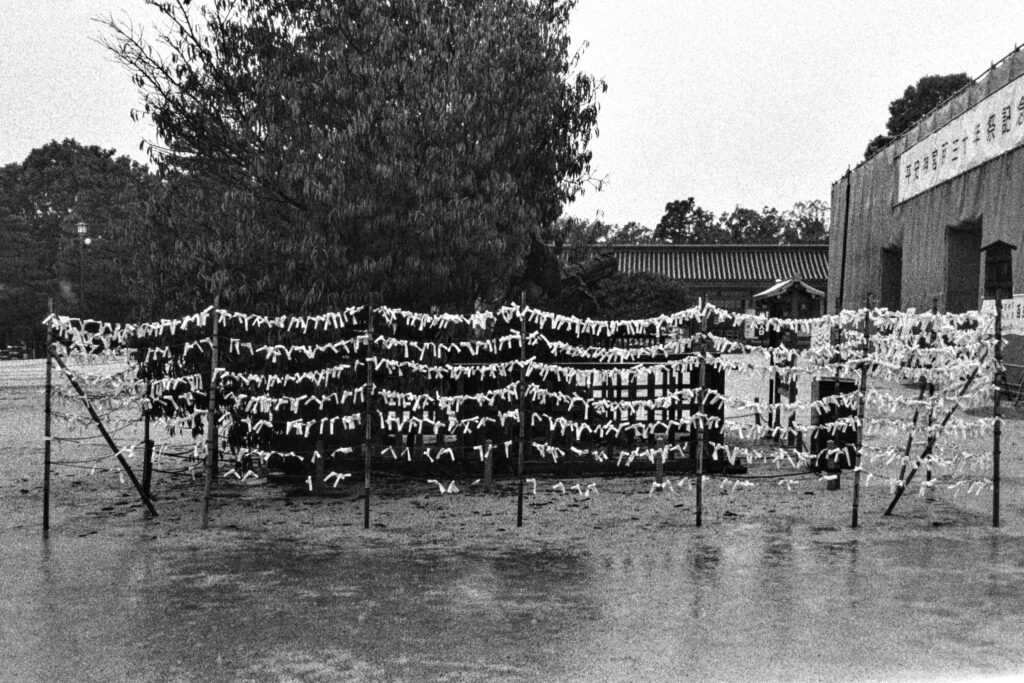

At the overexposure end of the scale, please refer again to my very overexposed photo above. As you will see, it doesn’t quite have the colour contrast and brightness of some of the other photos I took on that same day. (Such as the image at the top, or this next one)

I can’t find another example – I don’t publish or indeed keep many of my experiments – but over time I’ve exposed a few negatives like this and found this drop in contrast always there. What I determined is that what I was seeing in images like this was either the technical limitation of the scanner or the film. I’m not sure which, but actually in practice, it doesn’t really matter what causes the limitation. What matters is that within the film and scanner I’d chosen, I found the upper limit for overexposure before my photos start coming back lacking a bit of contrast. Actually in practise I decided that my absolute limit should be around 7 stops of overexposure – I mean how much overexposure does one really need…?

I then based my underexposure limit on where I found the line between a murky and non-murky photo coming back. In practice I found that if I underexposed by any more than about 1 stop, I risked getting murky scans. That 1 stop plus my other 7 gives me a maximum of 8 stops of room for error, which if you think about, is huge!

Practical implications

The practical implications of this are obvious. For a start, it puts an end to all that nonsense about the 1/1000 max shutter speed of a Leica film camera being an issue. It also helps with compact and more basic cameras that have even slower maximum speeds. My Voigtlander Vito B has a top speed of 1/200. But this isn’t limited to older film cameras. Cameras like the Konica Hexar AF for example only have top speeds of 1/250th. This is often stated as a disadvantage or limitation, but really – at least in terms of exposure – this can be solved with what I’m talking about in this post.

It also opens up the possibility of more easily shooting narrow depth of field or slower shutter speed photography in brighter light without the use of any neutral density filters. Which if like me you have some sort of built in hatred of filters, is definitely a bonus!

More than this though it allows – should you choose to embrace it – a very simple approach to shooting some types of negative film. My anecdotal tale of going up against a mates all-singling-all-dancing Canon was not a one off. In fact more often than not over the last year I have abused the latitude of my film in this way. Really – I’m almost ashamed to say – just because it makes life profoundly easier. In fact as I alluded to at the beginning of the post I’d go as far to say that I’ve become a little lazy (more on that later).

Back to my 8 stops room for error for a moment. Taking in to account that there is only 7 stops difference between f/1.4 and f/16. This means that using the sunny 16 rule as a starting point, on a bright sunny day if I set my hypothetical camera to 1/400 with 400iso film I should need to set the aperture to f/16. In practice because of my room for error I could actually take photos at f/1.4 in the same bright sunshine and still get a photo that – once density is corrected in the scan – looks like it was normally exposed. Of course this is a little extreme, but the fact that it’s possible certainly open up a certain level of freedom within your shooting disciplines.

Achieving this for yourself

The beauty of all this is that unlike most of my posts where I’m extolling the virtues of x-camera or y-lens – or something else that can involve considerable investment on your part – in this case the only investment I’m recommending is in film and time. You don’t even need to change the film you shoot, or even the scanner you use.

Yes, you could go out and buy a load of Portra 400 and get it Noritsu scanned by AG or Richard Photo Lab or Mein film lab or whoever else has a Noritsu. If you don’t give them instructions to the contrary, shoot your Portra 400 photos within that 8 stop range and your photos will likely come back density corrected to look like normally exposed photos.

But why follow my path? I’ve chosen the path I have as I just happen to like what overexposed Porta 400 looks like when it’s Noritsu scanned specifically by AG. You might not. That being the case, you just need to experiment with the film/films that you do like. Try overexposing. Shoot a film a different levels of under and overexposure and see what results come back when you either send your scans off or try and scan them yourselves.

I’ve found that Portra 400 gets more colour-contrasty when it’s overexposed. Colours become more vibrant and in my mind very pretty, especially with a Noritsu scanner which in itself natively produces warmer more contrasty results.

Fuji 400h seems to get less vibrant, and actually in my experience doesn’t give such broad room for manoeuvre. These are both professional grade films, but there are stacks of consumer films that will likely give a vast range of different outcomes.

The point I’m trying to make is that experimentation and finding what film and level of overexposure right for you is key. Most would recommend as a general rule keeping it within about 3-4 stops of overexposure. I say they are probably right, but really, what harm is there in experimenting?

Beyond that, it’s just a case of finding a scanner, or someone to scan your negatives in a way that you like the look of. As a general rule, cheap mini lab scanners can’t cope as well with over exposure. The same can be said for cheap home scanners. But go to a pro lab or buy a good scanner and you should find your room for error in exposure increases.

The problems with density correction

Of course all of this does bring up the question of how to under or overexpose your photo for effect. What if you want your photo to be really bright or indeed really low key? If density correction always returns a negative film photo to the point of looking normally exposed, how do you either under or overexpose on purpose and see the result in your photos?

Quite simply this comes down to your chosen approach to scanning. If you scan at home, you can choose the exposure of the scan in the process of scanning yourself – this is of course the main virtue of home scanning touted by those who do it (it’s also my main motivation for buying my own Noritsu, but that’s story for another day).

The problem with sending your photos away for develop and scan is that you’re effectively leaving the decision about what each frame should look like in the hands of the computer or person operating the scanner. This basically puts a big chunk of your creative process into the hands of someone or something else. This is something that many people find a hard pill to swallow, despite the fact the getting your negs scanned professionally almost always results, objectively speaking, in high quality images. Fortunately, there are a few ways to retain that creative control.

Obtaining a “look” from a lab

To make things slightly more complicated, different pro labs seem to have different looks, not to mention different scanners. Some will tell you about how they try to capture the native look of the film, some will tell you they can make your photos look pretty much how you want them to look, and some like AG will just send you scans that they have deemed look right with little input from you. None of these ways is necessarily right or wrong, but again, there are plenty of companies to try, its just a case of experimenting and finding what suits you best. What is consistent to all pro labs is that they will all tell you that for best results from you negative film to aim for some level of overexposure. From that point its just a case of finding the lab that makes your photos look how you want them to look!

Retaining creative control when using a lab

There are a few possible solutions to the problem of having someone else scan your film. The first is as simple as having a good relationship with the company you use. Talk to them, tell them your expectations and desires from your scans – some companies will be more accommodating to this than other. Some companies actually offer it as a service. UK film lab and Richard photo lab come to mind as two companies that offer a custom service that maps your desires to their process on an ongoing basis. There are many photographers that are quite vocal in their praise of such services.

But actually it doesn’t need to be as complicated or in depth as that. Some other companies like Carmencita offer simpler approach. As part of the ordering process with them, you make some basic specifications about colour, contrast and brightness which they work to when they process your film.

There is a third, and in my opinion even more simple approach to outsourced scanning. Or at least there is an approach that I’ve found suits me best. What I’ve found is that if I have my scans returned to me in TIFF format they give me just enough room to adjust the exposure to taste in post. TIFF files have per-pixel data, they are not compressed like JPEG files where the compression allocates single colours to whole areas of adjoining pixels. What this means is that within reason, your TIFF files can be adjusted to taste in your own post process software without too much degradation to the image.

What’s important here is that once again there are options. Whichever path suits you best will come down to your own experimentation. Try having a conversation with a company like UK Film Lab, try using the Carmencita ordering system, and try using someone like AG to get your scans back as TIFF files so you can process them a bit if you feel the need. It’s your photography, you have to make it work for you in a way that feels most comfortable to you!

Caveat emptor

Before I conclude this post, I just want to touch on something I’ve mentioned a couple of times in the post: my laziness. In practice, just because you can shoot Portra at EI 1.6 doesn’t mean you should.

Many would also argue that shooting film like this is shooting it well outside of how it is designed to be used. In many people’s opinion, shooting like this results in technically worse image quality. I am sure they are right too – but really, if you are happy with the results shooting this way, who’s to argue with you??

That being said, this massive room for manoeuvre can – as it has in me on more than one occasion – led to laziness. Not needing to think about anything other than framing, focusing and setting the aperture to suit is a wonderful thing, but after the novelty wears off it’s hard to avoid the feeling that one is somehow cheating. This sense of feeling like I’m cheating has on occasion led me to feel less fulfilled by the process, and feeling less fulfilled by photography is something that I feel quite strongly about avoiding.

This is exactly why I have spent the last year also trying to find myself a light meter that works to subtly rein me in a bit without impacting too much on the speed I am able to work – I’ve now found one, in fact it was finding a light meter that suited me that inspired this post – but more on that another day.

What I’ve found is that I’ve got to a point in my film photography where I feel like I’ve learned the rules. I’ve then learned how to break the rules with some pretty outrageous abuse of latitude. I’m now learning to get the same consistently good results as quickly as I have been, but without taking the abuse of the latitude so far – the journey never ends does it?!

So to conclude

Fundamentally, all this should be about advancing your skills and quality of photography – and despite the title of this post – not about finding a way to cheat or bluff your way to good results. With the right film and scanning process you can abuse the hell out of the latitude, and actually it’s a lot of fun doing it as part of the process of learning to obtain great results more consistently. But ultimately it shouldn’t be about the abuse of latitude, it should be about the well considered good use of it instead.

Ultimately, some negative film has lot of overexposure latitude, you’ll either be well aware of this and be in on the trick, or you won’t. If you’re not, you really must give this sort of experimentation a go. It will help you understand the properties of negative film better, open up some creative possibilities and methods of shooting that give a sense of freedom like little other. But more than anything else – as it has in me – it should help you find a path to consistently better results in your negative film photography.

Cheers for reading,

Hamish

Some interesting links:

Film stock overexposure comparisons – UK Film Lab

A scanner comparison – Carmencita

Share this post:

Comments

Stephen on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

I wish you had made this post a week ago Hamish... I have been using an M2 for the past year, I have tried various light meters, including the MR (which I couldn't read... old eyes), the Lumu (too much messing around), and a couple of iPhone apps, the best one being Pocket Light Meter (Nuwaste).

Nevertheless, I was still getting too many poor results, so I thought I would go for the built in jobby... I have bought an M6 on Saturday morning. I did go for the .85 viewfinder, so all is not lost, and it is an M6, so it can be used without a battery... But imagine if had bought an MP, or worse an M7, when what I really needed was this most valuable and very late lesson in film latitude.

The answer seems to be, learn the sunny 16 rule and then overexpose righteously. OK I'll give it a go. :)

As far as processing goes, I have always processed my own black and white and in the last couple of months, having been badly disappointed by the performance of the labs that I chose... Mentioned in an earlier comment... no names no pack drill. I have discovered that colour processing is even easier than black and white. I scan with a Nikon Super Coolscan 4000ED with its own software, and an old PowerMac Quad with Leopard.

Incidentally, there is a great portrait photographer and latterly film director called Anton Corbijn... He has been saying for years that he never goes faster than 1/30 and he prefers 1/15, in order to get movement, so he must have been doing what you are suggesting, just not explaining it in the same way.

He makes good films too!

Anyway thanks for the lesson, even if it is a little bit late, what's another camera between friends?

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Terry B on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

David Askins-Gast on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

JKLPHOTO on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Regarding color film (or colour if you prefer) Portra does seem to love "overexposure", although I would say exposing for shadow detail is just proper technique (since it is a negative film). Pro labs always advised us against "gross overexposure" for two reasons: color-crossover and extended print times. The latter was mostly a production-speed issue as a "bullet-proof" negatives take much longer to print. Since they were both density correcting as well as color correcting, gross overexposure could lead to some funky color crossover, especially in shadows.

What are your thoughts/experiences with exposing B&W films? Do you use the same process?

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Vernon L Szalacha on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

I do have a question about the post processing aspect. When shooting Portra 400, with a roll that has varying degrees of overexposure, is it best adjust the scan for each negative and tweak it slightly on the computer or scan the whole roll and deal with the TIFFs later?

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Aukje on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Marco C on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

I should find a way to force my old scanner to do some sort of density correction, or buy some white leds and do it manually ;-)

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

walker on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

Comment posted: 02/05/2016

kievm on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 03/05/2016

Comment posted: 03/05/2016

Comment posted: 03/05/2016

Frank Lehnen on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 03/05/2016

Well the negatives are dense, but the scans come out very well.

Of course with those cameras I don't really have the choice concerning exposure...

Comment posted: 03/05/2016

Ken Hindle-May on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 03/05/2016

I might have to give overexposure a try. A couple of months ago I spotted a rather lovely Yashica Lynx 5000 at a tabletop sale and immediately fell in love with the look, feel and build of the thing. Unfortunately, a dicky light meter meant I've been forced to use a handheld meter while shooting and to be perfectly honest, I hate it. I've benefitted from being 'slowed down' by film, but this is a step too far. If I can just take one reading when I take the Lynx out of the bag, dial in a 2-3 stops of overexposure and then get going then it might be worth keeping after all.

I might have to experiment with Superia 400 to see how much overexposure that will take, as it's cheaper than Portra and in my experience, a bit less sensetive in terms of storage. I've had good results with it in my Holga even on days that are really too sunny for 400 film.

Comment posted: 03/05/2016

Comment posted: 03/05/2016

Comment posted: 03/05/2016

Ric Capucho on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 03/05/2016

When I first got my Leica M6 I well remember chasing the exposure arrows around the viewfinder, and worrying if I'd got it just so. Coupled with the focus chasing I used to do, I missed shot after shot. Daft really, in hindsight. Now an f/8 and be there kind of chap.

More recently, when my (first, an SE) Rollei 35 arrived, I shot off 2-3 rolls before realising I'd totally ignored the light meter, and just did my own thing. Snowy days, overcast and misty, ISO 400 film (HP5 ) so it got the f/8 and 1/125 treatment... and all was well. Recently, using the replacement 35S I did something similar, and shot off two rolls walking through shadowy/bright streets, and never changing the exposure even once. Sod it. All shots were useable, which leaves me with a thought:

About time I returned to the streets with my M6. Hyperfocus, and exposure set exactly and only once by smelling the air, and I reckon the experience will be very different. Can concentrate on pointing the camera in the right direction and pressing the shutter.

Ric

Comment posted: 03/05/2016

Martin Hugh Henley on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 03/05/2016

A related question for everyone: Is Portra 800 shot at iso400 preferable to Portra 400 shot at iso400?

Comment posted: 03/05/2016

Comment posted: 03/05/2016

Cheyenne Morrison on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 04/05/2016

I had a Minolta and we would put this in the back of the film door as a guide to refer to easily. Here is a good one ....

http://bit.ly/26Rfb0T

Nick Thompson on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 04/05/2016

If not should I keep the film at 400 and adjust the exposure manually with the shutter speed to get the equivalent 1 stop?

Thanks

Nick

Comment posted: 04/05/2016

Leo on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 04/05/2016

Thank you for the excellent advice. I shot two rolls of Portra 400 metered at 200 and will see what happens. By the way, how would you overexpose pushed film, say HP5 400 to 1600 during daylight? Thanks!

Comment posted: 04/05/2016

Eddy on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 05/05/2016

Comment posted: 05/05/2016

ehpem on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 06/05/2016

UK Film labs have a couple of useful blogs about overexposure with numerous examples at different /- EV values from Portra 160, 400 and 800, Fuji 400H and Tri-X 400. This link shows the various posts http://ukfilmlab.com/?s=exposure test

Ant Lockyer on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 07/05/2016

Comment posted: 07/05/2016

Comment posted: 07/05/2016

KJ Vogelius on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 12/05/2016

Great write up as usual Hamish!

Comment posted: 12/05/2016

Nuno Cruz on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 21/05/2016

Comment posted: 21/05/2016

Comment posted: 21/05/2016

Comment posted: 21/05/2016

Neil Woodman on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 01/09/2016

Comment posted: 01/09/2016

Comment posted: 01/09/2016

Comment posted: 01/09/2016

Comment posted: 01/09/2016

Comment posted: 01/09/2016

Comment posted: 01/09/2016

Comment posted: 01/09/2016

Terry B on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 12/09/2016

As you do your own scanning, have you ever considered that there is the possibility that your scanner could be contributing to the issues you are having with grain? I have two scanners, an old Minolta Dimage Elite Scan II, of 2001 vintage, and a Canon 9000F flatbed that can scan film up to 5x4. The old Minolta is a dedicated 35mm film scanner and produces visibly sharper results, but at the expense of grain. The Canon produces almost grain free results but, in comparison, produces noticeably softer results with 35mm. For a reason I can't fathom, the Canon performs much better with medium format negs. In Lightroom, do you have a grain reduction function? This may help.

Michael on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 15/09/2016

How are you liking your Noritsu scanner? Which model did you get? I'm in the market for one as consumer grade scanners I'm having difficulty with and love scans I get from the lab with the Noritsu. Did you have to get any special software for it, or did it come with it? I'm having a terribly difficult time finding good information on the internet with people who have Noritsu scanners at home. Thanks!

Mike

Comment posted: 15/09/2016

Comment posted: 15/09/2016

Tina Kino on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 04/11/2016

Comment posted: 04/11/2016

Neil Woodman on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 12/06/2017

Nick on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 13/06/2017

Comment posted: 13/06/2017

zoran vaskic on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 05/05/2018

But of course my big concern in venturing into film apart from creative composition, is exposure. Your article is a big help. A couple of years ago I wasnt interested enough to want understand the point you are making here Hamish. But today I wanted to understand and you made a great, simple, informative point. Point taken and thanks again. I've finally made plans for purchase of home developing supplies, a competent (so to speak relatively speaking) scanner, and a new computer unit. Decided it was time to act. When i got drawn back into photography three years ago I never knew film would draw me though I've been slow to respond. The whole photography thing began from a recognition of a love of still images, especially colour in my case though I appreciate the amazing black and white people that people create. Theres a lot to wade thru to try to understand getting into photography let alone film photography for a novice. But your overposure explanation is already making me feel a whole lot better about my prospects. I plan to definitely implement it in practice.

Comment posted: 05/05/2018

zoran vaskic on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 07/05/2018

I found, accidentally, this quote a few days ago, and I thought it to be very true. I know this is straying into philosophy and one wonders, how does it connect to overexposing colour film? But I think it does, maybe someone will read and see, yeah, it may connect to overexposing colour film after all.....

" There is only you and your camera. The limitations in your photography are in yourself, for what we see is what we are." Ernest Haas

Some people will brush this off. I happen to believe its very true though and not just 'deep' jargon with no connection to reality. Things in life...photography....are not hard, but rather the things we deal with internally sometimes overwhelm us, and then we dont have the energy, the wherewithal to handle photography or much else in life. But if we say, this is too hard, that is too hard....photography is too hard....I think its actually a mistaken and misleading assessment.

Comment posted: 07/05/2018

RicD on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 14/05/2018

A few of my cameras (50 and more years old) their shutter speeds were actually one or more stops slower, never faster. After the CLA I saw a difference in negitive density. Shutter testers can be purchased online. If you see your shutter is off then a tech should make the repairs, or compensate from there, now you are working from accurate values.

You mentioned light meters, my two are the Sekonic L-358 and the Lumu that plugs into the iPhone headphone jack. Yes, the Lumu is as accurate as the L-358, and very small. In use the Lumu is too futzy. Connect it to the iPhone headphone jack, turn on the iPhone, open the Lumu app, take readings. The Sekonic, turn it on take a reading. Down side of the L-358 is its size in the pocket, that is where the Lumu wins. The Sekonic can be used onehanded, the getting the Lumu ready requires two hands. To effectively use the lumu on site it is best to leave it connected to the iPhone and the iPhone set to not turn off, otherwise when you need to use the Lumu you will need to login to the iPhone. The process of getting to the Lumu app is slow, the L-358 it is consideribly quicker.

On a side note: in your article there are misspellings, i.e. there a few you that should be your or you’re, same with the word to, that should be too.

Very much I appreciate your article and the folks that responed with their input. Thank you

Comment posted: 14/05/2018

Comment posted: 14/05/2018

Francis on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 16/06/2018

BTW here's a YouTube clip illustrating the latitude of Portra.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T3OIzjhu9eo

Understanding Shutter Speed, Aperture, Film Speed (ISO) & The Relationship Between Them - 35mmc on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 25/02/2019

Learning the basics of color print film photography – James Li on Overexposure latitude or: how to cheat your way to perfect film photography

Comment posted: 06/01/2023