(Featured image; Photograph taken by friend; all rights transferred to User:Mdd4696, CC BY-SA 2.5 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5>, via Wikimedia Commons)

Whenever we use a camera to record a scene, we are transforming analog signals. Each element introduces yet another error, albeit small.

The perfect is the enemy of the good

It’s an apt saying. The followup is

What is good enough in a complex system?

Errors propagate in complex systems. Redundancy has its benefits. It’s natural. And there are optimal settings to achieve reasonably accurate results.

Errors and more errors

We are carbon-based life-forms. Our body continually produces copies of DNA – almost perfect copies. But not quite. That’s why… Let’s not get morbid.

Scanning film results in an imperfect copy. Even just making an image on digital sensor (or film) is imperfect. By its very nature a digital sensor samples the image producing a fixed number of pixels at each scanning resolution. And there are limits beyond which higher resolutions will degrade the image (think lenses and stopping down further and further). There are sweet spots.

The sweet spot – an example

The only digital camera I have is an iPhone. But I can demonstrate the sweet spot easily using a digital scan.

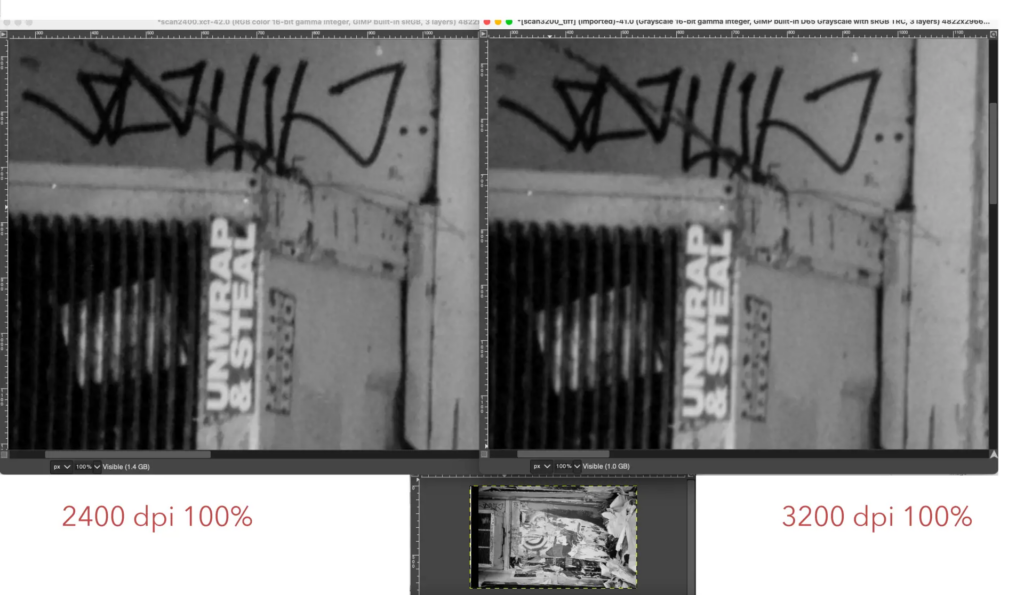

The next two images are closeups of the result of scanning a b/w negative at the maximum resolution [3200dpi] and one at a lower resolution [2400dpi] both scans include a portion of the unexposed portion of the film, with parts devoid of film markings. While negatives were converted to positives and “colour corrected”, there was no sharpening. The scans were output as RAW 16 bit greyscale. The colour correction included removing the affect of the colour cast of the film base, inversion, cropping to the expose portion and then adjusting levels so that the brightest potion of the image was white (255) and the darkest was black (0).

And zooming in, it is clear that the 2400dpi scan is slightly sharper than the one at 3200dpi. This is expected and documented in many places on the web.

So more pixels is not necessarily better – when by “better” we mean “sharper” and by sharper more line pairs per mm. The question really is how sharp does the image have to be? That depends on the output medium and the intent. After all a photograph is an interpretation of a scene. In Ansel Adams’ words

“The negative is the equivalent of the composer’s score, and the print the performance.” Ansel Adams

Two other examples demonstrate the problems in “capturing” an object with a “camera”. These examples that are relevant to using a digital camera to create images either in the digital (digital camera) or analogue realm (film camera), as well as to scanners.

Photocopying

Photocopying is not perfect. Photocopy a letter, photocopy the photocopy and repeat. Eventually the text in letter will be a blur. Reason: errors propagate. But they even propagate within a system.

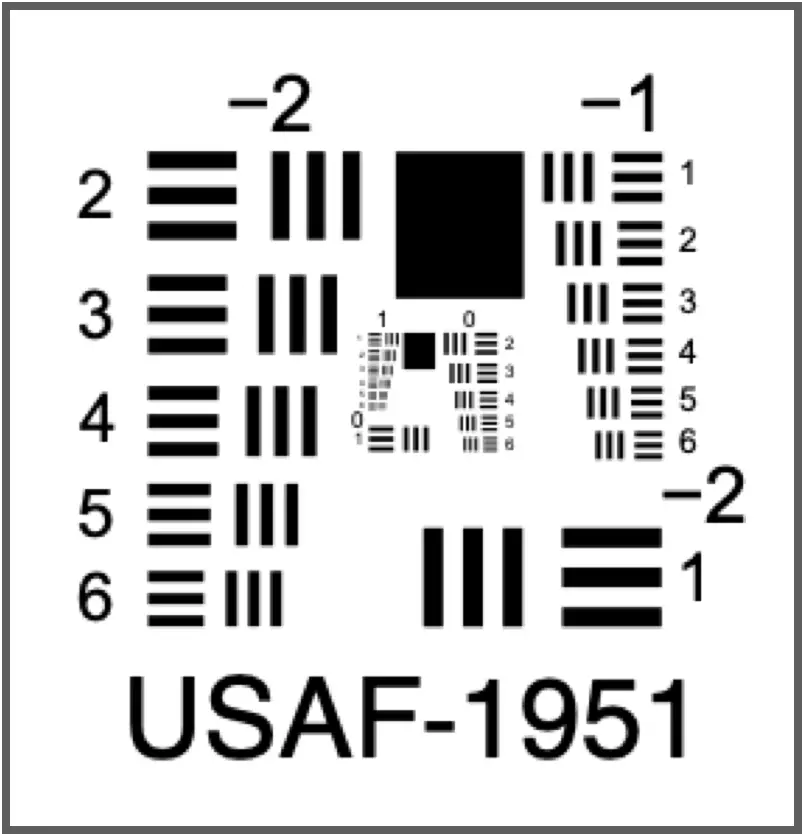

Consider, photocopying a page in a book. How and where the book is placed matters when copying a particular page:

- Noise. If the scanner glass has dust or fingerprints in the area being scanned, they will affect the photocopy.

- Out of focus. If the page does not lie flat on the scanner glass, parts of the page will be out of focus and darker (underexposed).

- Missing data: If vital parts are too close to the edge, they may not appear in the photocopy. If the page is not positioned properly on the scanner glass, the photocopy may be missing parts of the page.

- Skewed. If the book is crooked, the copy will be crooked.

- Light pollution – Since the cover cannot be closed all the way, light will be scattered and, as a result, interfere with the “rendering”, resulting in a muddied copy. A grey background rather than a white one.

- Blurring. Movement before or during the scan. If the cover is held down by hand, the book may move before or during copying, resulting in a skewed copy or even one that is blurred.

And so on …

Slide copying

In the past, slides were copied with cameras. This is highly relevant to digitising negs. In fact it is a precedent. It was a laborious process.

The equipment:

- Film camera.

- A macro lens capable of 1:1 rendering.

- Slide reproduction film.

- Slide returned from a lab in its holder

- Copy stand for holding the camera above the slide to ensure that the film plane and slide are parallel

- Holder for the slide to keep the slide square and the film flat,

- Light source to illuminate the slide evenly at the proper colour temperature.

- Fairly dark space to eliminate stray light from interfering with the illuminated image.

And then the operator will have to focus the camera precisely.

And then there’s dust. Dust in the air. On the slides. In the lens.

For slide copying the variables are: resolution and colour fidelity of the film, the aperture setting to optimise resolution, the fidelity of the light source, (even and correct colour temperature), the precise focusing, the lens, vibration, the skill of the operator. It was complicated. Each element introduced an error. And errors propagated, becoming worse with each succeeding step.

The connection to digitising negs is obvious. Best practises for slide copying have their equivalent in digitising negs and also in photographing small objects at life-size or larger and other subjects.

Resolution

That camera may have 50 mega-pixels but that is the optimal, theoretical number, which is dependent on the other elements being perfect, introducing no errors. But they will, of course.

Would you rather buy something that you can use out-of-the-box or would you prefer to construct it out of elements that you choose, knowing that each element will need to be properly vetted? Think of the time and the agony of choosing. And the regret. Buyer’s remorse. That certainly applies to a digital scanning setup. But it also applies to ordinary in-the-field photography. Think lens, camera, sensor/film.

How can we evaluate how good even the camera can be?

So the stated resolution is 50 mega-pixels. But that’s only one element in the chain of error propagation. Lens, filter, sensor, image processing system, storage device. In that closed system. It is a theoretical upper bound, the most/best one can expect. After the camera lens does its number, it is less. After the camera corrects for the fact that each pixel only registers red, green, or blue, it is even less, for example, during a process known as demosaicing or even with less error-prone pixel-shifting.

Line pairs per mm [lp/mm]

One measure of image resolution is the number of line pairs per mm, that is to say the number of lines that can be distinguished from each other, rather than melding into a blur.

The actual resolution of 35mm original camera negatives is the subject of much debate. Measured resolutions of negative film have ranged from 25–200 LP/mm, which equates to a range of 325 lines for 2-perf, to (theoretically) over 2300 lines for 4-perf shot on T-Max 100 Kodak states that 35 mm film has the equivalent of 6K resolution horizontally according to a Senior Vice President of IMAX

The sensor/film

So if we knew the resolution of the sensor with a perfect lens and used the line pair metric, we would still only know the upper bound. But that would not be what we observed.

And doubling the number of pixels, does not double the resolution, instead it is less than 1,5x [hint square root of 2, 1,416…]. To double the resolution, the number of pixels has to be quadrupled. So to have twice the resolution of a 25 mega-pixel sensor will require a 100 mega-pixel sensor. Pricey. And to what end?

What is the true resolution of that digital camera? How many line pairs can it distinguish? Or does it anti-alias to eliminate the artefacts of demosaicing, effectively reducing the resolution of line pairs per mm? Do we have to look under the hood?

The measures of resolution

- Number of pixels – a rather crude measure which reveals very little about the acutance of the recorded image. Pixels per mm or inch will be a measure of how precise it is but it is only a crude measure. It won’t account for common anomalies like smearing, colour shifts, colour fringing etc.

- Spectral resolution – the ICC profile or colour space these are device/media dependent. It is actually considerably more complex and includes way of mapping from one space [display] to another (e.g. printing on a specific paper).

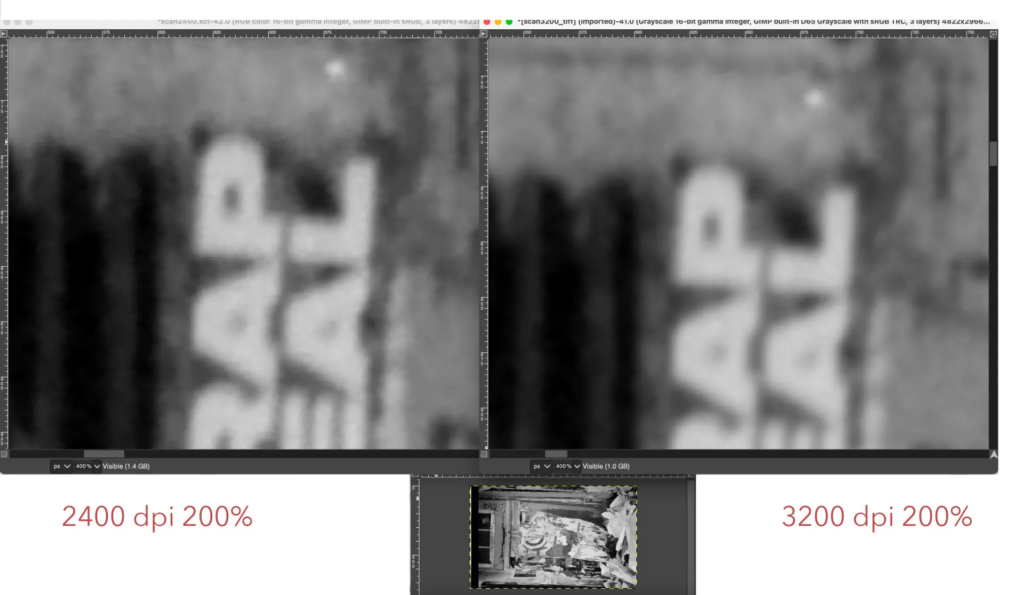

- Spatial resolution – in general this is the distance between independent measurements, For images this is the “resolving” power of the medium. It is usually expressed in terms of line pairs per mm. This means the number of lines in a millimetre that can be distinguished from one another, usually measured with a target like this.

-

Remix of Setreset, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons At some point the line pairs dissolve into a blob, since they can no longer be distinguished. Just like photocopying a photocopy and then photocopying the result ad nauseam. Copies of this target are available in transparency or on paper that can be scanned as a film negative, scanned as a reflective document or reproduced using a lens to determine the accuracy (spatial resolution) of the lens/film/sensor. There are other ways of measuring this, for example, using a Modulation transfer function (MTF) which is less reliant on the visual perception of the observer and the contrast of the media.

- Colour depth – number of bits per colour channel, in RGB space for displays/sensors and some variant of CYMK space for printed output. For digital cameras and scanners, the maximum colour depth for greyscale is 8 bits per channel (16 bits if there is an IR (infrared) channel) and for colour 48 bits (64 bits if there is an IR channel). JPG files have at most 8 bits per channel or 8 bits in grey scale and 24 in colour

The lens

But there’s a wrinkle – a lens does not have the same acutance over the entire sensor/film. So it depends on where you measure the line pairs/mm.

There are other considerations even with perfect lenses. For example, how will the output be viewed. And from what distance and under what lighting conditions. Perhaps upping the resolution will have no effect on the final image. Then you’ll be spending for more resolution that you won’t necessarily use. Add in the variability of the human visual processing system and… you get the idea.

This is tedious. So many questions. They keep popping up. Like the heads of a hydra.

My Solution to all this

Just pointing out the issues. Doesn’t mean I’ve solved them. Or necessarily made peace with them. I’ve taken another route. Having spent so much time working with computers – graphics, quality assurance, user experience, and more – I prefer the analogue approach, the slow contemplative nature of film, the wabi sabi. But I do tweak the images with computer programs. I’m not that much of a Luddite. And yes, I have made darkroom prints and still develop b&w at home. But I much prefer the digital print-room to the wet-darkroom. The noxious fumes. The setup. It seems so crude to me now. And other impediments. While the computer provides more tools to manipulate images, I prefer to use as few of them as possible: curves, spotting/healing, cloning etc. I do not want to be stuck in the endless hole of just one more fix until the image becomes soulless and inert.

Share this post:

Comments

Richard Politowski on “Digitalitis” and the Folly of the Pursuit for Perfection

Comment posted: 02/06/2023

The other scanner issue has to do with fine dust and grime on the scanner bar, lenses, and mirrors in the path of the imaging. Over time, all of these accumulate the finest patina of dust, invisible at a glance, but enough to trace one's initials in under the right lighting. Some of these may be easy and obvious to clean but others are internal and would be riskier to disassemble to reach. The blur caused by this "dust of ages" would affect the finest details at the highest contrast and thus wouldn't really show up, say, in the smooth surfaces of a face. Turns out the resolution targets would be sensitive to it and decrease the numbers obtained from them, particularly true in a transparency/negative scan and less so in a reflective scan. And we make the most use of higher resolutions in film scanning where we need it the most.

Of course, if there is no scanner bar involved, then the resolution gets down to the chip and lens involved which each have its own practical limitations. But using a lens cleaner to be absolutely sure they don't exhibit the slightest amount of haziness, some of it barely visible, is important at the highest contrasts of highest resolution imaging.

And finally, flare. Stray light from the edges of objects being scanned as well as from internal reflections in the scanner can destroy apparent resolution. Black tape, black paper, etc., can be employed to reduce the internal flare level dramatically. It matters.

Comment posted: 02/06/2023

Richard Noll on “Digitalitis” and the Folly of the Pursuit for Perfection

Comment posted: 02/06/2023

I see your points as a technician or a scientist but not as an artist. You alluded to the concept at the beginning qouting AA. The fact that the performance can establish a perfect, desirable quality that the copy of the source fails at should be embraced. Syntactical analysis of books disregards many mundane statistics of the work, yet analogue copies of them containing many errors have little effect on people appreciating and coveting them.

Comment posted: 02/06/2023

Geoff Chaplin on “Digitalitis” and the Folly of the Pursuit for Perfection

Comment posted: 03/06/2023

Interesting article, thanks.

Jeremy on “Digitalitis” and the Folly of the Pursuit for Perfection

Comment posted: 03/06/2023

1. You can get 80mp out of 35mm if you use the proper taking lens, emulsion, and conversion. That's about the limit (currently). To achieve that, you'll need a Sigma 40mm Art or 105mm Art, film such as Adox CMS 20 II (TMX 100/Acros II/Delta 100 come close), and then for digitization, a Sony A7R4(or R5), or a Fuji GFX 100, with native modern glass (100 and 120mm respectively). Pixel Shift hi-res must be used. This will yield 60mp of real resolution. There is more there, this transfer appears to incur maybe a 50% data loss. Printing in the darkroom and then scanning the darkroom print on a v850 gets you to 80mp of real resolution.

2. My Epson v850 gets ~2700ppi, averaged across horizontal and vertical. From a quality perspective, mine works better scanning 3200 then downscaling vs scanning at 2400 then upscaling. Results can vary wildly on flatbeds, so this may not hold true for others.

3. The dynamic range is superior using either the A7R or GFX as the converter vs. PIE XAs or V850, but only by a hair, and it's very scene/emulsion dependent.

4. The grain structure is superior on traditional scanners due to the color filter on the cameras (when not using pixel shift). If you use hi-res sensor shift composite, then the de-mosaic due to the composite mostly mitigates the grain distortion.

5. The Primefilm XA Super has superior resolution vs. Coolscan 5000, but *only* if you use manual focus and tune it. Tuned, you get ~4300ppi out of it, which equates to ~24mp. However, the XAS is a fragile POS, I don't recommend it, I'm on my 3rd now and it just broke again. I am now waiting for the pending "XE Plus" model release, which I intend to use instead, since it will supposedly scan much faster and have updated dynamic range. I also tried the XE Super, which gets about the same as resolution as the Coolscan, but the XEs gets less dynamic range vs Coolscan.

6. The Olympus EM-5mk2 is a fantastic cheap option for digital conversion, paired with the 40mm F2.8 TTArtisan 1:1 macro. It yields 64mp 4:3 raw files with a real resolution of ~40mp from a 645 frame. I found this combination limited in terms of dynamic range though after using it extensively and comparing to the XAs, Epson, and K70.

7. Pentax bodies that support pixel shift are a fantastic option for conversion workflows. They work some serious magic in their compositing. They have *better* dynamic range than the A7R composites, better than the GFX single-frame, and they have zero distortion in the grain structure. That being said, they're crap for tethered shooting. I own the K70, but I'm going to assume it only gets better with newer bodies.

8. The Plustek 8300i I tested was good, but inferior to the XE Super in both resolution and DR. They scanned about the same speed.

After all this, you may wonder what my workflow is? I kept shooting medium format, as the emulsion and workflow requirements to get medium format resolution out of 135 were severe. These days for 35mm I use the K70 as primary conversion device with a Valoi holder on a mk1 Negative Supply copy stand and a 95CRI light source. I pass the film through a Kinetronics Staticvac prior to it passing through the Valoi, and dust is practically non-existent. I use the same setup for 120. I use NegMaster BR for the initial inversion and finish in DxO Photolab, so I have no monthly Adobe tax.

I fall back to the V850 or the Primefilm when I have A) damaged film where ICE helps, B) need more medium format resolution, or C) I think it may look better using trad scanning. I get ~32mp out of 645 and ~55mp out of 6x8 when using the Epson. I may eliminate keeping a 135 dedicated film scanner now that my XA Super died again. I really haven't used it that much now that I got the Staticvac K70.

Cheers.

Bill Brown on “Digitalitis” and the Folly of the Pursuit for Perfection

Comment posted: 03/06/2023

I'm still quite active in print finishing and digital darkroom methodology and my clients hire me specifically because I have made much effort in understanding how to reduce or overcome specific issues related to scanning, file manipulation and printing. I say being a professional is as much about knowing how to fix problems or mistakes as it is about knowing how to work with ideal conditions. To be able to serve my clients best and to help them achieve all they desire for a specific image I must understand as much as possible about the methods involved in the process. I must also know how to separate actual from theoretical detriments when it comes to real world situations and viewing environments. I am one who has disassembled a scanner to clean the inside and the results were certainly worth the effort. As much as I am a technician I am also an artist and this blend certainly impacts my processes. Craftsmanship as a technician and craftsmanship as an artist can certainly look totally different. My job is to figure out how to merge the two in a way that is beneficial in the everyday world of print production.

All the minutiae that you mention in your article are real issues but ultimately what methods are employed to offset these issues is where the art happens. Hopefully, each performance is nuanced so as not to induce the boredom of redundancy.

Thanks for the thought provoking words.