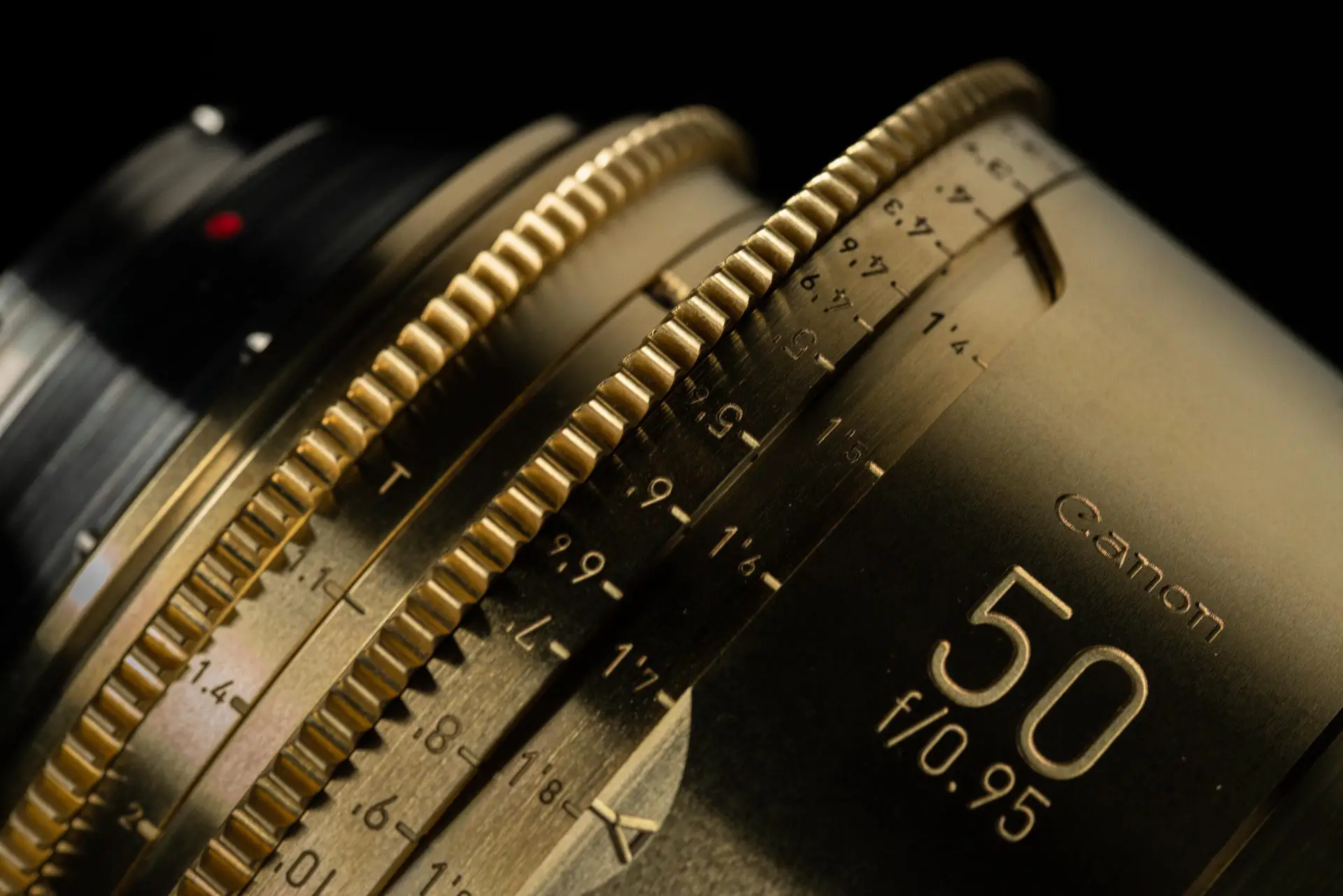

Not so long ago, Kosmo Foto reported on the fact that the latest Zack Snyder film, ‘Army of the Dead’ had been entirely shot with Canon 50mm 0.95 “dream” lenses. Reading that article triggered something in my memory. Sometime in 2019 I travelled down to London to catch up with Alex Nelson from Zero Optik. He was over from California for an event, and after becoming pally through chatting on instagram we had decided to take the opportunity to meet up.

Over coffee, Alex had told me about one of his clients – a Hollywood Director – who he had recently worked on a series of these Canon lenses for. I couldn’t remember if he had told me who the director was, but reading the article made me wonder if it had been Zack Snyder and this new film.

Later that day, I dropped Alex a message on Facebook and after a bit of a chat about lenses and working with Zack, I decided it might be interesting to interview him for 35mmc about the work he does and some of the differences between the cinema and stills photography worlds when it comes to the use of vintage glass. The following is a slightly edited transcript of the email conversation that followed.

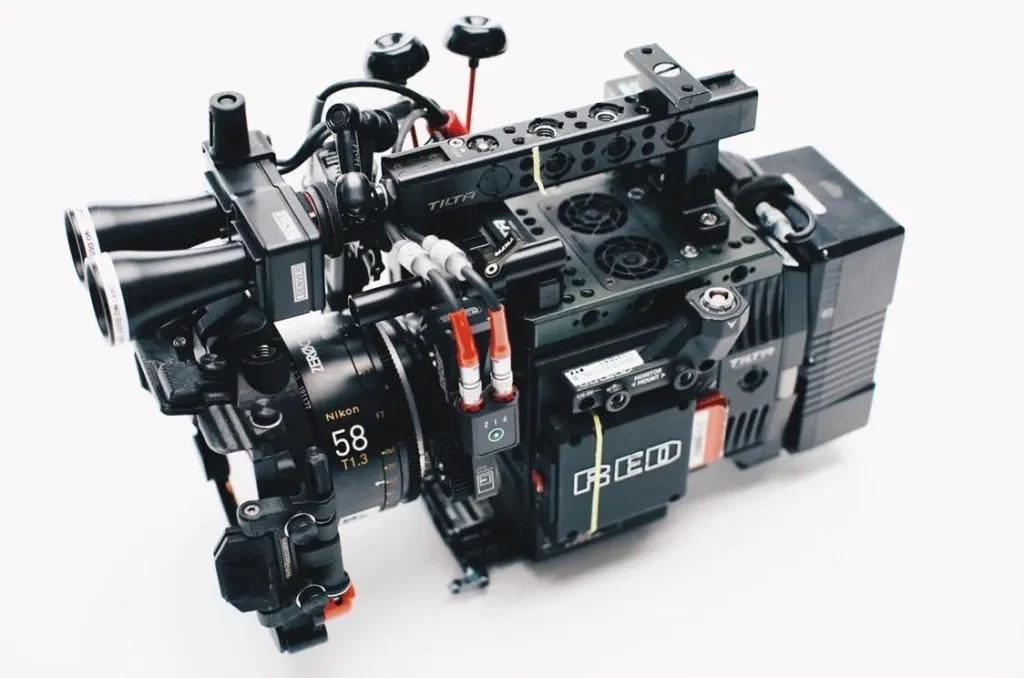

H: So, Alex, let’s start with a bit of background for those reading this who don’t know who you are or what you do. In my head, you’re still the guy who made the cinema-spec pinhole lenses (hence Zero Optik?), but that was a long time ago now though, right? I can’t even see them on the website anymore. What I can see is a lot of conversions of lenses my readers might recognise that have been shoehorned into housing that are probably almost unrecognisable to most photographers. What’s the deal here, what exactly is it that you do?

A: It’s a great question and something I think even many of my clients would struggle to answer fully. We’re one of about half a dozen companies worldwide that specifically adapt vintage lenses for cinematography.

The cost and degree of effort involved varies widely from one company to the next, but our approach is to use as little of the original lens as possible (besides the optics themselves, obviously). The reason for that is based on the extreme precision cinematographers require of the lenses they use. Focus has to be repeatable within a fraction of a degree, same for aperture scales, and performance has to be as consistent as possible from one set to the next.

We work with lenses that can be almost a century old and rebuild the optics into new mechanical housings that have 320 degrees of focus throw, accurate T-stops (as opposed to f-stops), and all of the features needed to interface with accessories like matte boxes and remote-focus motors. It’s like building Rolexes from vintage lens parts and provides a creative option to filmmakers who aren’t interested in using the more modern glass that’s available off-the-shelf.

H: Ok, so I think I know the answer to this question, but why? What’s the attraction, why are people like Zack Snyder interested in using this old glass when so much exceptional new glass exists?

A: Zack, in particular, is a great camera and photography aficionado, so his interest in shooting with 1960’s Canon rangefinder glass was well-researched. Generally, though, our clients have two main goals when they work with us: they want lens options that are more interesting and unusual than what’s available from traditional manufacturers and they want a unique edge over other cinematographers who all have access to the same cameras and filtration options. There is a high degree of filmmakers searching for a sort of “secret sauce” that they can call their own.

Vintage lenses also allow cinematographers to meet the rigorous technical requirements that studios like Netflix mandate (4k deliverables, for example) without the images looking too sharp or sterile. There is a strong correlation between the exponential improvement in sensor technology and demand for our products.

H: So there is almost a rebellion against objective quality then? I’m interested to know how accepted this sort of approach is in cinematography? I feel like in stills photography the idea of choosing the perfect lens is more often than not boiled down to the objectively “best” lens. I, as you know, have different ideas about what makes the perfect lens, but I feel like those of us who use imperfect, vintage, characterful (choose your own adjective) lenses in stills photography are often seen as the odd ones. Is that the same in cinema, or is the world of cinema more open to less-than-perfect optics, would you say?

A: It is extraordinarily common, especially relative to the still-photo community. In stills, particularly in the realm of digital photography, there is a widespread pursuit of technical perfection and unrelenting pixel-peeping. Cinematographers, by contrast, have almost the opposite compulsion.

Part of it, I think, comes from the fact that photographers are allowed to develop a style and approach of their own while cinematographers are constantly being asked to develop unique aesthetic treatments for each and every project they shoot.

Some, such as Roger Deakins, consistently shoot with the same high-performance lenses and use lighting or post processes to achieve that goal. Many others, though, see each project as a chance to explore new tools and methods, and that’s our market. A period film, for example, may be shot with soft vintage Cookes from the 1920’s or 30’s to give an ethereal glow and lower-contrast look than would otherwise be possible with filters or software. Given the almost limitless range of narratives to be told, there is enormous demand for lens choices that are nearly as varied in character.

H: Ok, but that’s in the world of Hollywood, or at least bigger-production film making. What I find interesting is that even in the hobbyist world, flare, lower contrast etc seem more accepted in moving pictures than they do in the stills world.

I wonder if this is simply down to the fact that pixel peeping is not really an option or that viewing distances are more established in moving pictures? Or perhaps it’s simply down to the fact that subjective “quality” is just based on a different set creative goals. Do you have any thoughts?

A: I think it’s the result of diverging goals between photography and narrative cinematography. With a few exceptions, still photographers have always placed a premium on removing as many technical barriers as possible from capturing scenes as faithfully as possible. There are certainly plenty of examples of photographers deliberately shooting with vintage lenses or unusual optics, but those are almost always presented as experimental outliers.

Narrative filmmaking, on the other hand, places a premium on capturing scenes in a way that feels complementary to the story being told. That gives filmmakers license to explore the full spectrum of lenses and filtration so that no single aesthetic is seen as a radical departure from how films are “normally” recorded.

H: So what about Zack and these 50mm 0.95 dream lenses then? He shot some of Army of the Dead handheld himself didn’t he? He was the director and cinematographer then? Is he cut from a slightly different cloth again? Is he a particularly creative director, or are there others like him?

A: Zack is definitely cut from a different cloth in that he’s embracing a kind of auteur approach that only a handful of other directors even attempt. Among his many other roles, he was both the cinematographer and one of the camera operators on ‘Army of the Dead’ and those Canon 50mm f/0.95 Dream Lenses were integral to his vision for the movie.

That said, there are a lot of directors who take a specific interest in the lenses used on their projects, even if they’re not also the cinematographer. I think those tend to be the kind of creatives who gravitate to us because we specialize in unique and unusual optics that will influence things like blocking and shot design more than the average high-performance cinema primes.

H: Interesting, so when Zack came to you, was the conversation about converting the canon specifically, or is there some conversation about lenses that might help achieve a look he has in mind? To what level do you have those conversations about how to achieve a look?

A: Zack was already committed to using the Canon 50mm f/0.95 and 35mm f/1.5 rangefinder lenses, so the discussion was more about how to meet the extraordinarily short timeline we had before production began that Summer. Zack had already thoroughly researched and tested dozens of lenses prior to landing on these, so his mind was made up by the time we were tasked with making the Canons set-ready.

In fact, most of our clients have a similar process whereby they conduct their own tests and market research to see what will best suit their project or (in the case of rental companies) their clientele. It’s our job to pay attention to the demand for specific lines of vintage lenses and to offer an easy way to accommodate lenses we don’t already have designs for. It’s rare that a cinematographer reaches out to ask about achieving a particular look rather than working with a predetermined set of lenses.

H: Ok, so what about the sourcing of the lenses themselves. Do you help source the glass? I seem to remember you talking before about a cinematographer who had come to you with a lens that wasn’t in great condition, but that the poor condition was actually something that added to, not subtracted from the look as far as they were concerned. Is it part of your work to help these guys find glass, and how is that process specified?

A: We get a lot of inquiries about turnkey sets or sourcing lenses, but the bandwidth required to source, inspect, and refurbish vintage primes on speculation is not insignificant. We do, however, try to guide our clients on best practices for buying and evaluating optics. There have been instances where clients actually want haze, fungus, or coating damage and that plays into the widespread interest in finding a “special look” that is unique to a particular filmmaker or cinematographer.

H: It’s interesting isn’t it. In photography, even in the search for classic lenses, the goal is often to get the “best” copy. I have found myself enthralled by the new Meyer lenses recently as they offer something of a classic feel to the rendering without the pitfalls of having to search for a lens that doesn’t have fungus, haze, separation, etc. But really, there’s no reason that something horrible in the glass can’t add rather than subtract when the goal is to create something unique in terms of image quality. For all that though, do you ever wonder if this is a trend that’s self-destructing if that’s what these folks are resorting to?

A: If you’re asking whether the interest in repurposing vintage still-photo lenses for cinematography is self-destructing, I’m inclined to say “no”. I think it has fostered a widespread appreciation of what makes individual lenses or manufacturers unique and that is actually feeding an interest in the role that optics actually play in making images.

I think photographers are, as you said, interested in acquiring the “best” equipment. That can mean having the highest-resolution sensor, the sharpest lenses, or even vintage lenses in immaculate condition. The goal in all of those scenarios is to have gear that imposes as little as possible outside of the anticipated on the images one is creating.

For the cinematography community that goal is reversed. There are scores of “perfect” lenses available for rental on every continent, and those do get plenty of work still, but they are often seen as boring or unimaginative. Filmmakers have a greater interest in making the quirks of their capture medium made apparent to viewers than many photographers might.

H: So maybe photography has lost its way then? Is the never ending cycle of bigger, better, faster, sharper from the large majority of manufacturers damaging creativity in the world of photography, do you think? Is cinematography inherently more creative, or perhaps more ahead of the curve when it comes to creativity do you think?

A: I don’t believe one medium is more or less creative than the other. Cinematography is inherently dynamic and can therefore play freely with subjects falling in and out of focus or a light flaring the lens for a moment. No single frame of a movie has to stand up to technical scrutiny because when the credits roll you’re left with the sum total of hundreds of thousands of frames. Those frames are also elevated by sound and given purpose by the writing, acting, and editing, whereas a photograph must stand on its own and present a coherent artistic vision in one silent image. I don’t think that makes photography a less creative endeavor, just one bound by different rules and expectations.

H: Great answer, I enjoy your personal photography a lot, so I had a feeling you might have a good answer to that!

Ok, so what are you working on now? Anything cool you can tell us about? Or are your clients quite secretive?

A: We have a very aggressive development schedule mapped out for the next two years, but we’re forced to be secretive to avoid tipping off the competition. What’s most exciting to me, though, is the growing slate of film and television projects to which we’ve contributed releasing in the next several months and over the course of the next year. The work we do at Zero Optik merely paves the way for filmmakers to realize their own, more public vision. It’s thrilling to be able to facilitate that vision and the alchemy that occurs when talented artists are given the tools they need to explore the limits of their creativity.

H: Ha, thanks Alex, a very diplomatic way of saying “I aint telling nuttin that’s gonna be published”… and fair enough too! You’ll just have to keep me in the loop about the lenses that are about to rocket in value, right?!

Joking aside, this has been really interesting, thank you! Care to share some links for how people can read more about what you do?

A: It’s been an honor and a pleasure, Hamish! Our Instagram feed is probably the most dynamic way to explore more of our work and get some insight into the process, but we’re also re-tooling our website (www.zerooptik.com) to offer a broader array of technical information and articles to help demystify how our lenses are designed and built. Of course, I’m always thrilled to come back and chat more with you, as well!

Share this post:

Comments

Troy Phillips on Vintage Lenses in Cinema vs. Photography – Finding that “Secret Source”

Comment posted: 02/08/2021

I can push and pull on things a bit more even at higher iso numbers. And many of these old lenses are sharper than you’d think .

I’ve been shooting wild mushrooms and flowers with them for a couple of years and you get that ethereal look and I like it . I tend to shoot them wide open up to f/4 a lot .

I also shoot live music videos and do not like the stark high resolution look everyone does. I use them mixed in with high resolution lenses . We want a cinematic look and feel to our work . We work at drawing the viewer in and creating an in your head experience as though you are at the concert live and how your mind works at the show . We don’t want that in your seat one perspective feel that distant and unconnected that many live shows give you .

Michael J on Vintage Lenses in Cinema vs. Photography – Finding that “Secret Source”

Comment posted: 03/08/2021

Donato Rondinelli on Vintage Lenses in Cinema vs. Photography – Finding that “Secret Source”

Comment posted: 03/08/2021

Bud Sisti on Vintage Lenses in Cinema vs. Photography – Finding that “Secret Source”

Comment posted: 04/08/2021