In 2016 I travelled to Rohingya refugee camps in Burma and Bangladesh to shoot portraits of the people living there with a Fujifilm GA645. I was interested in the plight of the Rohingya, an ethnic and religious group referred to as ‘the most persecuted people on earth’.

Little was reported in the media in 2016, and I had no idea that the situation would escalate so dramatically only a year later, when nearly a million people flee from what is now widely regarded as a genocide.

My first stop was Rakhine state, in western Myanmar (Burma). Here, I was granted access by the local military commander to enter what are termed Internally Displaced Peoples (IDP) camps.

In 2012, tens of thousands of Rohingya had been forcibly displaced from their homes and interned in such camps, where there was a lack of electricity and running water, and open sewers.

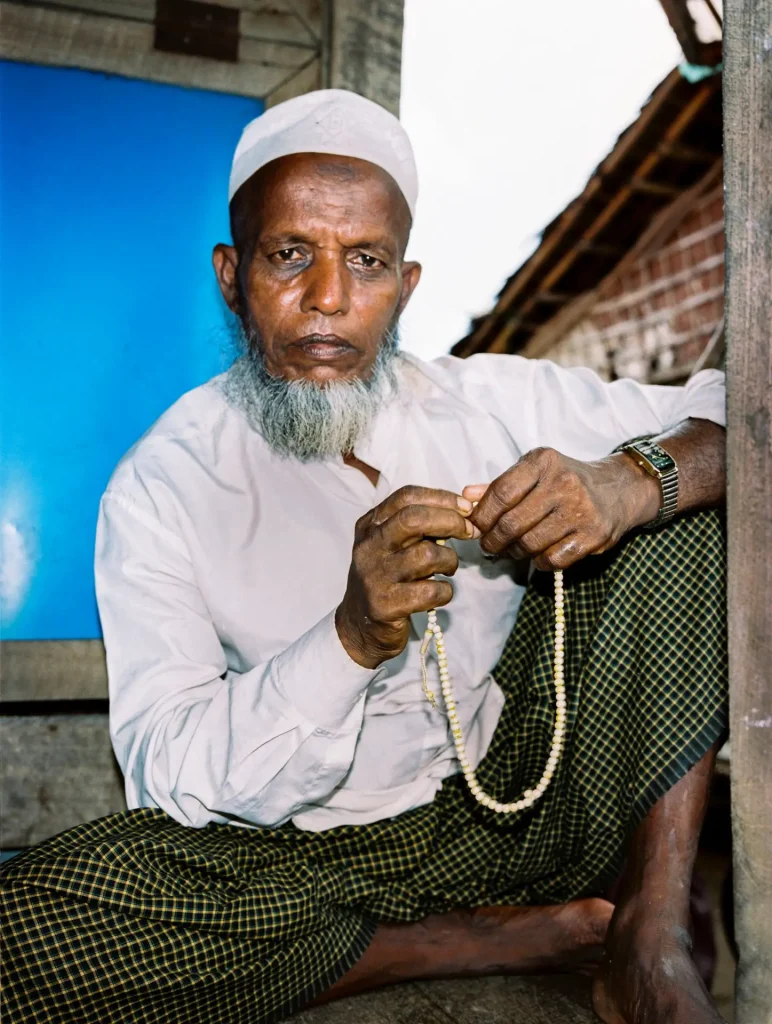

The Rohingya I met and photographed told me about the severe repression their communities had already been experiencing at the hands of the Myanmar government over many decades. This included a denial of citizenship, restricted movement, arbitrary imprisonment, torture, and even killings.

Photographing in this environment proved challenging, especially on film.

The monsoon rains and the crowds of people meant that even something as simple as changing a roll of film became an anxious process.

Fortunately, a Burmese friend of mine was able to translate for me and was invaluable in the process.

I also managed to speak with Rohingya people in a countryside village. Here also, they spoke of the hardship they endured, including discrimination, political exclusion and restricted movement. The villagers also told me how Burmese Buddhists would attack the village, set fire to their houses, beat the men and rape the women.

It was a confronting situation, and I felt awkward asking for photographs. However, the Rohingya people were generous in this, and on both occasions, I managed to shoot a few portraits with my Fujifilm.

The next stage of my journey was to travel to Teknaf, in southern Bangladesh where a quarter of a million Rohingya had already been living in refugee camps from a previous mass exodus in 1991 and 1992. Here, my luck did not hold out and I was arrested, detained and questioned at length by the Bangladeshi Army (who threatened a lengthy prison term) after only shooting a handful of photos.

I eventually made it back to Australia where the photographs would be featured in a number of media outlets, including The Guardian and SBS.

The photos also become a touring exhibition titled Rohingya: Refugee Crisis in Colour.

Although the trip had personal risks for me, the photographs ended up being a valuable educative insight into the Rohingya people and the ongoing persecution they face. This was especially so given western Myanmar became closed to foreigners in 2017, and remains so.

As part of the exhibition I also engaged a local Rohingya group in my home city of Melbourne to speak at openings and related events.

This was vital in ensuring that the Rohingya were involved in the project and that the photographs served to advocate on behalf of their community. Through this process we were able to raise vital funds for medical and education aid.

Despite the poor living conditions in both Burma and Bangladesh, I found the Rohingya people to be proud and resilient, a quality I wanted to capture in my photographs.

While using medium format film proved a challenge under the circumstances, I feel that the quality of the photos gave an added presence to the portraits.

While admittedly very simple photographs, I believe the humanity, strength and resilience of the Rohingya shines through – not due to my photographic skills, but because of the essence of the people.

‘Rohingya Sorrow’ Short Documentary Screening

As part of this project, I have been working with a young Rohingya refugee to produce a short documentary titled ‘Rohingya Sorrow’.

Shot on a cheap mobile phone, film maker Mohammed Aziz provides a glimpse into everyday life in a refugee camp – the world he was born into and the only home he has ever known.

Please join me on Monday May 3 for the online premier of Rohingya Sorrow and a presentation about my 2016 photograph series.

To register by donation, follow the links below. All proceeds go to a school in a Rohingya refugee camp.

Monday 10 May: 8pm Melbourne time zone – register here

Monday 10 May: 8pm New York time zone – register here

You can view more of my work at www.alimc.com.au and follow me on IG @alimcphotos

Share this post:

Comments

Michael J on Shooting Medium Format Film in Rohingya Refugee Camps (and Getting Arrested in the Process) – By Ali MC

Comment posted: 03/05/2021

However have you ever felt, or felt others' judgement, that shooting film in such a front-line photojournalism project is a bit perverse? One imagines it's quite high risk- you can upload or bank digital images via cellphone and they're out of the reach of a bad-tempered guy with a uniform and a gun who could wreak havoc on a load of exposed and unprocessed film in a matter of seconds... I'm glad you've found widespread interest in running the pics.

Ali MC on Shooting Medium Format Film in Rohingya Refugee Camps (and Getting Arrested in the Process) – By Ali MC

Comment posted: 04/05/2021