I learned about Hydra during my university years. I was in a ‘Leonard Cohen phase’ and learned that he lived on the Greek island during an early phase of his life. Fast forward fifteen years and I was planning a trip to Greece. Scanning over a map, the name triggered the memory and I did some digging to learn more about it. Hydra is a small island a couple of hours boat ride south west from Athens. One of its claims to fame is that the island doesn’t allow motor vehicles on it. Instead, donkeys move the majority of cargo around the tight, narrow, and steep paths of the Hydra township.

I was shooting on an Olympus OM-1 with Portra 160 35mm film. With me were a trio of Olympus Zuiko lenses: the 50mm which I used the majority of the time; the wider 28mm which was especially useful when shooting within the tight corridors and paths of the township; and the softer 100mm which I used when up on the ridgeline of the island to compress buildings, trees, and rocky outcrops against the wider landscape.

Hydra is a small island. Just fifty square kilometres with an exacting hardrock spine that runs east-west across the island. Either side of the spine are imposing cliffs and gentler dirt slopes leading to the stoney beaches dotted around the coast. In the middle of the ridgeline sits Mt Eros at a height of 600 metres. Hydra township, the only town on the island, has two thousand residents and sits on the northern coast in the shadow of Mt Eros.

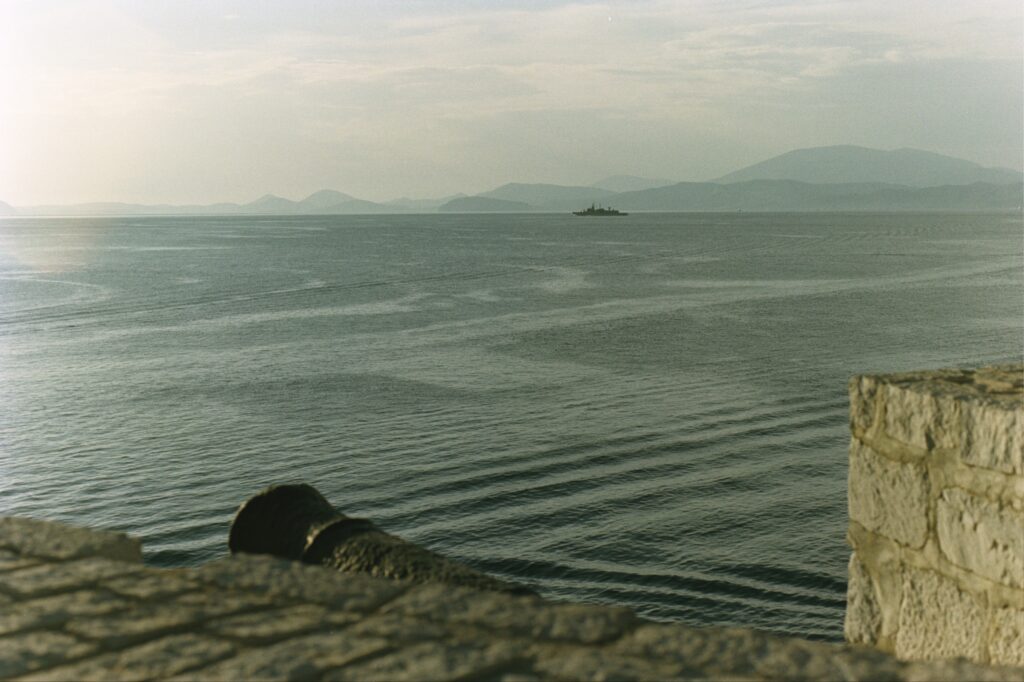

My explorations took me to the summit of Mt Eros. From Hydra township, a wide cobbled path zigzags its way up the dusty hill. The ascent is marked by the transition of white washed houses to ruined buildings where the town has receded, to small farm paddocks, through pine forest, and eventually to above the tree line on the island. After an hour of walking the path reveals its purpose – Prophet St Elias Monastery sits on a ridge overlooking the Peloponnese on the other side of the strait.

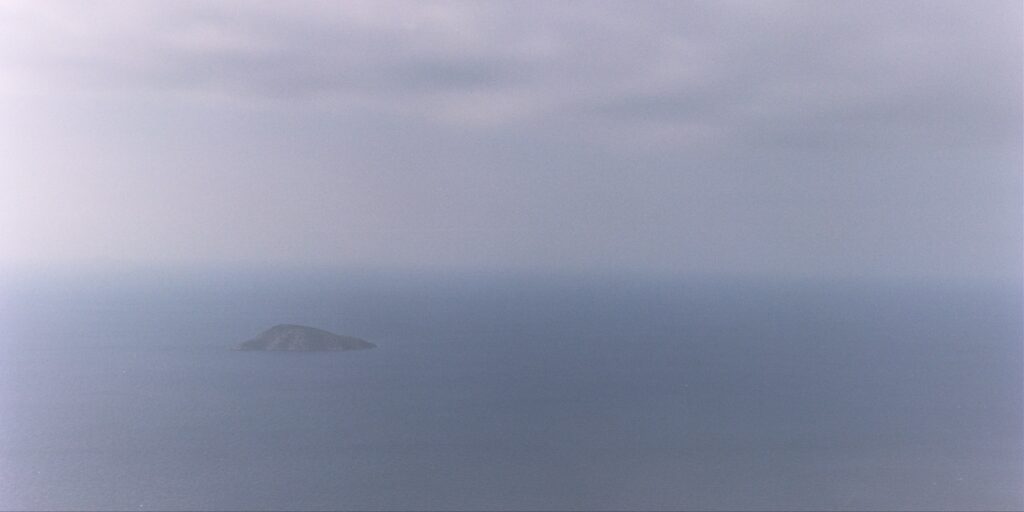

Another forty five minutes of ascent and one reaches the summit of Mt Eros which presents a complete view of the island and surrounding geography.

Descending the summit and walking west takes one along the ridgeline spine of the island. Great cliffs, gigantic rocks, and centuries old stone walls are set against the barren background of dust and pebble.

Up here, in the middle of nowhere, with no one about. Another church and a torn flag flying in the breeze.

The scrappy trail ends at Episkopi, just a handful of buildings forming what looked to me like an olive farm. Like the rest of the walk it was completely deserted. Then down a gentle farm road back to the northern coast, and another hour and a half east back to the Hydra township.

During my time on the island I shot seven rolls of Portra 160, about half of these were from the walk described above. Months after my trip, once I had scanned and processed the negatives, I saw that I had around sixty strong frames. No individual unicorn frames, but the sum of them all formed a cohesive representation of what I saw and felt while on Hydra. This was completely unexpected and new for me. Most of my trips usually yield up to a dozen strong frames which don’t carry a lot of consistency in colour, tone, or style across them.

I thought about creating a photobook, something I’d never done before. I printed out every usable image in postcard size and spent weeks playing around with the image selection and ordering to tell the narrative of the most meaningful part of the trip – the day walk across the island. Through photographs (no text), the book tells the story of a morning arrival in Hydra township, climbing the hill to the monastery, up to the summit of Mt Eros, along the ridgeline of the island, descending to the northern coast, and walking back to the Hydra township at dusk.

An eye-opening and engaging part of assembling the book was the interplay between two frames across a left and right page. Two independently strong images might look ‘bad’ when displayed across from each other. Whether complementary or contrasting, all of the colour, composition, leading lines, subject, and mood determined the pairing of any two images. A simple example of this is leading lines. If either image has strong leading lines then you want to order them so they lead into each other, not out of the book.

I didn’t set out to make a photo book, but in retrospect I can see that my time on Hydra had the right ingredients to make one. There’s the truism that travel inspires photography – indeed the land, language, and landscape were new to me. You’re exploring, your eyes see new scenes, and you want to capture them to revisit them later. Aside from that, I was travelling independently with a light kit. This enabled me to do the day walk around the island, but also seek and revisit places when the lighting was right. I found my time on Hydra compelling. At the time I felt that I was taking good photographs (something rare to me), and in seeing the negatives I was proud of what I’d created.

There’s a more travel, less photography focused write up of the Hydra trip on my blog. You can view a gallery of all images, or get the same photographs in the printed book €3.50 Red Wine by Glass.

Share this post:

Comments

Russell Rosener Jr on Hydra on 35mm

Comment posted: 04/12/2024

Then there is the mental odyssey AFTER the voyage. Fascinating that you hit on the concept of "sequencing" images. My Graduate degree in Photography was at The Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester NY. I studied with curator and artist Nathan Lyons. in 1974 or so, he published the first book using this method of arranging photographs which reinforced and played off each other. There were no words to explain the book. It was simply his observation of the American "Social Landscape" as he saw it reflected in public spaces. That first book was called "Notations in Passing" and I bet you would find it useful.

Bradley Newman on Hydra on 35mm

Comment posted: 04/12/2024

Jeffery Luhn on Hydra on 35mm

Comment posted: 04/12/2024

What a nice set of photos and commentary. Dramatic scenes! Sounds like a dry hike of contemplation.

I've been to lots of Greek islands, but not Hydra. So many islands were 'de-nuded.' Stripped of trees and ground vegetation for wood fires, grazing, and olive production. This caused the top soil to wash away, leaving a rocky desert where a sub-tropical island had been. Hydra supports a fraction of the population it did 1000 years ago. The further from the mainland, the less the impact.

Were the locals open to being photographed?

Jeffery

Comment posted: 04/12/2024

Steviemac on Hydra on 35mm

Comment posted: 04/12/2024

I'd be interested to know how you went about creating the book, is there a template online?

Comment posted: 04/12/2024

Louis Sousa on Hydra on 35mm

Comment posted: 04/12/2024

Paul Quellin on Hydra on 35mm

Comment posted: 04/12/2024

Philip on Hydra on 35mm

Comment posted: 07/12/2024

I’ve been all over the Cyclades and as far west as Corfu, but never did make it to Hydra. Perhaps that’ll be next…

Thanks for sharing and making me feel like I was there.

Christopher Deere on Hydra on 35mm

Comment posted: 09/12/2024

Comment posted: 09/12/2024