‘It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.’

The opening sentence of George Orwell’s ‘Nineteen Eighty-four’ is, like the man himself, enigmatic and disorientating. Both ‘Nineteen Eighty-four’ and ‘Animal Farm’ have long been permanent fixtures in school and examination board syllabuses. So long have they been there that for the English-speaking speaking world to have ‘done them’ at school is to have ‘done’ Orwell. There is, however, much more to Orwell than these two old warhorses.

An imperial policeman who rejected imperialism. An Old Etonian who actively sought the company of tramps and underdogs. A veteran of the Spanish Civil War yet a pacifist by inclination if not in practice. An intellectual who was happy running a village shop and small-holding. A man who liked his pint and chatting to locals but was frustrated by their political naivety. And above all, one who considered himself a socialist yet vacillated between left-wing factions, critical of each of them. Orwell was all of these and all of these are represented in his other novels and more particularly in his essays, letters and war-time diaries.

A heavy-weight peg of an introduction on which to hang my lightly written tale.

Crooms Hill runs from Watling Street, the old Roman Road north of Blackheath, down the west side of Greenwich Park into Greenwich itself. First recorded in the 10th century it is possibly the oldest named street in London. In the wake of royal patronage of Greenwich courtiers and civil servants anxious to be at the centre of power built houses for themselves along its length. Eager to impress, their houses became in the words of that doyen of architectural historians, Nikolaus Pevsner, ‘the pride of domestic architecture in Greenwich.’ He continues enthusiastically ‘there are not many streets near London that give so good and sustained an idea of the well-to-do private house from the c17 to c19.’ To put it more succinctly, then as now it’s posh. In particular Pevsner singles out out No. 24 as being ‘especially pretty, with central bow and main doorway in it’.

And it was here at No. 24, overlooking the park, that Laurence O’Shaughnessy the surgeon brother of Orwell’s first wife lived. Orwell never legally adopted his pseudonym, to family and close friends he was always Eric Blair. So it was in this persona that Eric and Eileen would stay with with Laurence and his wife Gwen, notably after Orwell’s return wounded from the Spanish Civil War in 1937 and when convalescing from TB treatment in 1939. Orwell’s, or perhaps Blair’s, subtle distinction in referring to these stays as being ‘at Crooms Hill’ rather than ‘at Greenwich’ is telling.

It was after the outbreak of WW2 that the comfortable bolt-hole at Crooms Hill came into its own. Ambivalent as ever, Orwell’s letters to friends in early 1939 express strong anti-war sentiments yet by 1940 he was writing an essay, ‘My Country Left or Right’, in which he sets out his reasons for supporting the war. Easier said than done for a man of Orwell’s poor state of health. Efforts to do his bit in an active capacity proved frustratingly fruitless. ‘The govt won’t use me in any capacity, not even a clerk and I have failed to get into the army because of my lungs. It is a terrible thing to feel useless….’ he writes in a letter, 6th July 1940.

A recurrent theme of his letters and diary entries of this period is along the line of ‘I have practically given up writing…. I cannot write with this business going on.’ He was in fact doing some journalism and reviewing ‘which help keep the wolf from the backdoor’ but it brought in practically nothing. Eileen secured a post in the Censorship Department of the Ministry of Information which, while no doubt helping their financial situation, meant that she stayed with Gwen at Crooms Hill. As Laurence had joined the Royal Army Medical Corps and was serving in France she was also company for Gwen.

After spending most of January and February 1940 at Crooms Hill Orwell kicked his heels in Hertfordshire at Wallingford, whiling away time on the small-holding. ‘I am busy getting our garden dug & am going to try & raise ½ ton of potatoes this year, as it wouldn’t surprise me to see a food shortage next year’, he writes in a letter , 3rd April 1940 in which he also speculates on breeding more hens and going in for rabbits but ends, ‘Eileen would send her love if she was here.’ The effect of the wartime separation of families was making itself felt on the Orwells. In another letter of April 1940 he laments, ‘I am here alone, Eileen coming down at weekends when she can.’

To break out of the stagnation of his personal Phoney War Orwell sub-let the village store and small-holding at Wallington, moved to a flat near Regents Park and joined the local Home Guard. Then came the news that Laurence was missing during the retreat to Dunkirk and Orwell was tasked by Gwen and Eileen with haunting the London railway stations seeking information from returning RAMC units. Confirmation of the death of Major O’Shaughnessy on 27th May 1940 at Dunkirk was received in early June whereupon Eileen returned to Crooms Hill.

Situated so close to the park this was no place to escape the war. Orwell’s diary entry of 20th March 1941 reads, ‘Fairly heavy raids last night….A lot of bombs at Greenwich, one while I was talking to E[ileen] over the telephone. A sudden pause and a tinkling sound.’ Asking what it was he received the reply, ‘Only the windows falling in.’ A bomb had ‘dropped in the park opposite the house, broke the cable of a barrage balloon and wounded one of the barrage balloon men and a Home Guard.’

Greenwich Park overlooking the Thames on the approach to London’s docks was the site of barrage balloon emplacements and anti-aircraft guns. An area of open flat ground bordering on Crooms Hill may have been the position of one or the other.

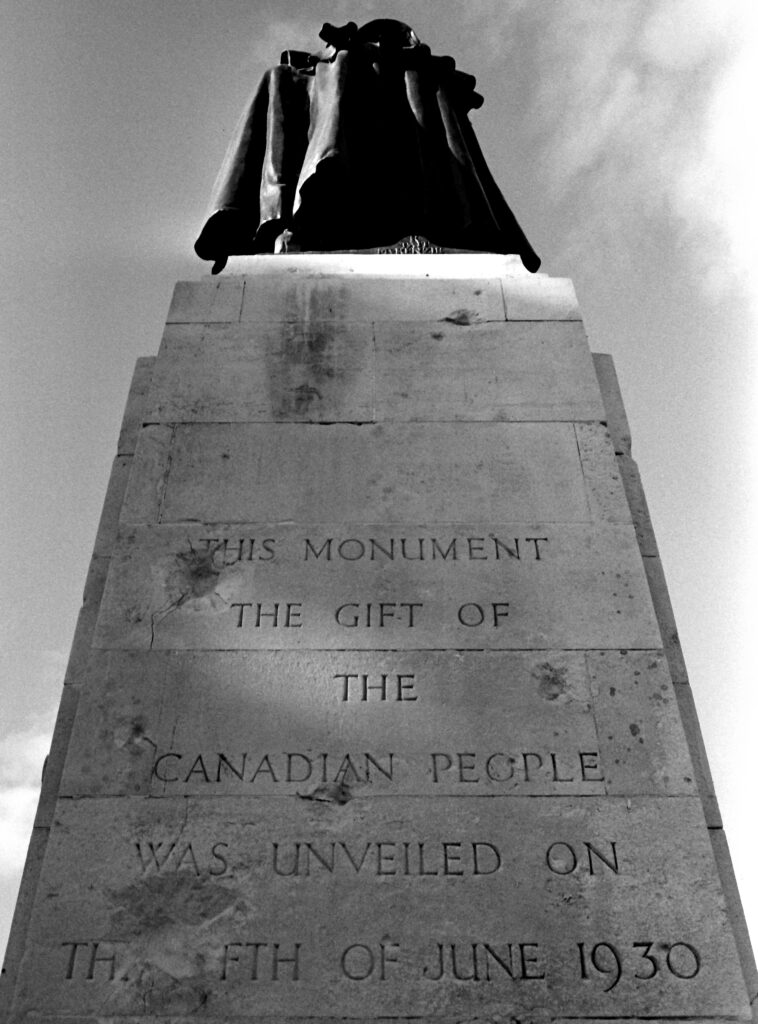

Its now has a Henry Moore sculpture which at least allows me to make the tenuous connection that at this time Moore would have been engaged on his series of drawings depicting people sheltering in the London Underground. A little further into the park and the plinth of the statue to General Wolfe still shows evidence of the damage caused when the nearby Royal Observatory was hit. Orwell considered the Observatory ‘the ugliest building in the world’ so may not have grieved had it have been destroyed.

Orwell had undertaken to write a regular ‘London Letter’ for ‘Partisan Review’, a left wing American publication. These letters were to take the form of an assessment of British morale, particularly that of ordinary people. By this time he had been spending more and more time at Crooms Hill to keep Eileen and Gwen company. Both women had taken Laurence’s loss badly so it must have been a sombre household and it might have been with a sense of relief to leave the house in order to conduct research for his letters. Chatting and listening to regulars in a local pub was his usual ploy and to do this he would only have had to walk a couple of hundred yards to the bottom of Crooms Hill.

It wasn’t always successful for his purposes. ‘People talk a little more of the war, but a very little. Last night E[ileen] and I went to the pub to hear the 9 o’clock news. The barmaid was not going to have turned it on if we had not asked her, and to all appearances nobody listened.’ reads a diary entry of the period. If Ye Olde Rose and Crown drew a blank there was always The Mitre. A little further into Greenwich along Stockwell Street, where Pevsner’s ‘shabby houses’ have been replaced by buildings in the modern idiom, it nestles beside St Alfege Church.

Both it and St Alfege were severely damaged by incendiary bombs in the same raid that blew in the windows at Crooms Hill as Orwell’ diary relates. ‘Greenwich church was on fire and the people still sheltering in the crypt with the fire burning overhead and water flowing down, making no move to get out till made to do so by the wardens.’ Orwell had previously paid a fact finding visit to the shelter in the crypt on 2nd March 1941. ‘Last night with G[wen] to see the shelter in the crypt under Greenwich church. The usual wooden and sacking bunks (no doubt lousy when it gets warmer), ill-lighted and smelly….G and the others insisted that I had not seen it at its worst because on nights when it is crowded (about 250 people) the stench in insupportable. I stuck to it, however, though none of the others would agree with me that it is far worse for children to be playing among the vaults full of corpses than that they should have to put up with a certain amount of human smell.’ After the fire, which destroyed the roof and gutted most of the interior, the church was restored.

Not that St Alfege was a stranger to re-emerging from ruins. The original medieval church collapsed in 1710. its foundations having been undermined by burials. It was rebuilt 1712-1714. A tower, in a variety of styles, was added in 1730 and encases remnants of the medieval building. Ironically, in view of its wartime use, the crypt was originally designed as a public space. The two churchyards were closed to burials in 1853 and the larger of these laid out as a garden and recreational space shortly afterwards. Renamed St Alfege Park it is accessed by a passage by the side of the church called, unsurprisingly, St Alfege Passage which has a fine terrace of Georgian houses uncharacteristically overlooked by Pevsner.

Given Orwell’s objection to children playing among the the vaults in the crypt I wonder what he would have thought of the park. Old gravestones are still stacked against the perimeter wall among the bushes.

But more than that, they are neatly lined up in the children’s playground. On the other hand, if the playing children and perambulating mothers had, as in so many parks, been supplanted by Dig for Victory allotments Orwell may scarcely have noticed.

The strain of living at Crooms Hill and holding down a more than full-time job began to tell on Eileen, ‘They are working her to death in that office,’ wrote Orwell in an earlier letter. On the verge of a nervous breakdown resigned in April 1941 and moved with Orwell to flat in St Johns Wood. As for Orwell himself, although he saw through establishment propaganda and resented having to toe the official line he joined the BBC in August as Talks Assistant, later Talks Producer, in the Indian Section of the Eastern Service. After four years of being a prominent feature of his life, Crooms Hill lost its importance.

There are two blue plaques in Crooms Hill commemorating notable residents. One next door to No 24 across the path to Gloucester Circus on the austere looking No 26 is for Benjamin Waugh, founder of the National Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Children. He didn’t actually live there though. Since his time the houses have been renumbered, what was his No 26 is now No 62.

The second one is down the hill at No 6 and is for the poet Cecil Day Lewis who lived there from the middle fifties. A man whose name Orwell included on a tongue in cheek list of crypto-communists he would have been encountered by both Orwell and Eileen during the wartime years. As he was Publications Editor at the MOI Eileen would have reported to him and Orwell’s journalism, particularly his London Letters, would have had to pass his scrutiny. There is no record of him using a bicycle although Orwell did when at Wallington.

There is no plaque, blue or otherwise, on No 24 to commemorate Orwell’s four year association with it. His official blue plaque is in Kentish Town on a house where lodged for a mere five months in the thirties and there are various non-official ones in London and other towns. Notably peripatetic as he was it is doubtful if Orwell would have been much concerned with bricks and mortar epitaphs. His work was all in all to to him and there must have been bitter-sweet satisfaction that his last two novels, coloured as they are by this period of personal tribulation and political exigencies, brought him acclaim and wide recognition. He knew his Dickens and may have wryly reflected on the opening line of a novel depicting an earlier era of social and political upheaval:

‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times….’

Primary Sources:

The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell. Volume 1, An Age Like This, 1920-1940. (Penguin Books, 1970)

The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell. Volume 2, My Country Right or Left, 1940-1943. (Penguin Books, 1970)

Orwell, The Authorised Biography. Michael Sheldon (Heinemann, 1991)

Secondary Sources:

The Buildings of England, London (Except the Cities of London and Westminster). Nikolaus Pevsner (Penguin Books, 1952)

St Alfege. A Memoir of the Restoration. Anon (Greenwich Parish Church, 1953)

Friends of Greenwich Park (www.friendsofgreenwichpark.org.uk)

Friends of St Alfege (www.st-alfege.org.uk)

Photographic Notes:

Minolta SRT101b, Minolta XD7

Vivitar 24mm f2.8, Rokkors 28mm f3.5 / 35mm f2.8 / 55mm f1.7

Ilford FP4+ / Rodinal 1:50 Semi Stand

Share this post:

Comments

Andrew Thompson on Orwell’s Greenwich – A Photo Essay

Comment posted: 05/01/2025

Wonderful supporting photographs. The one of St Alfege Passage is lovely.

Lived in London for many years, some of it just up the road in Bow so many visits to Greenwich.

Thank you.

Comment posted: 05/01/2025

Bob Janes on Orwell’s Greenwich – A Photo Essay

Comment posted: 05/01/2025

As a local lad, I'm slightly shame-faced at reading so much stuff that I hadn't been aware of..

Comment posted: 05/01/2025

Nick Lyle on Orwell’s Greenwich – A Photo Essay

Comment posted: 05/01/2025

Comment posted: 05/01/2025

Bill Brown on Orwell’s Greenwich – A Photo Essay

Comment posted: 05/01/2025

Comment posted: 05/01/2025

David Pauley on Orwell’s Greenwich – A Photo Essay

Comment posted: 05/01/2025

Comment posted: 05/01/2025

Jeffery Luhn on Orwell’s Greenwich – A Photo Essay

Comment posted: 05/01/2025

What a great essay supported with exceptional photos! Very high quality!

Of course I read Orwell in college, as millions of others have. It would have been a wonderful thing to have had your piece back then to understand his time and context. I'm sure Orwell, his family, and millions of his countrymen felt that despair and destruction might prevail, but they soldiered on. 'The Greatest Generation' is a well deserved moniker.

In northern California we have nothing of enduring historical significance like you do on your side of the pond. In my area there's Mark Twain's cabin and the hotel where the present owners claimed he shared a room with the famous singer, Jenny Lind. False. She never visited California. Anything that's 100 years old is extremely rare here. I'm inspired to take another trip to the UK!

Thanks for your photo essay!

Jeffery

Comment posted: 05/01/2025

Geoff Chaplin on Orwell’s Greenwich – A Photo Essay

Comment posted: 06/01/2025

The article is a serious piece of research, well written and illustrated, thanks again.

Comment posted: 06/01/2025

Russ Rosener on Orwell’s Greenwich – A Photo Essay

Comment posted: 06/01/2025

Comment posted: 06/01/2025

Leon on Orwell’s Greenwich – A Photo Essay

Comment posted: 06/01/2025

Comment posted: 06/01/2025

Stefan Wilde on Orwell’s Greenwich – A Photo Essay

Comment posted: 06/01/2025

what a wonderful and personal insight into the connection between Greenwich and Orwell! I am, as always, very impressed by your work!

I, too have a local historischen project ongoing about the year 1939. But so far, it lacks a personal angle - your piece certainly doesn't.

Can't wait for your next post!