Sometimes in life, we may be fortunate enough to stumble upon a place which delights the senses, quickens our imagination, and yet soothes the soul at the same time. One such a place I have found is the church and churchyard of St John the Baptist in the hamlet of Hope Bagot, Shropshire. Nestling in a small steep valley which in turn rises up to the top of Clee Hill where, as the song says, ‘On a clear day, you can see forever.’

This church is small, simple and somewhat humble. It is mercifully unburdened with gothic excess, yet with the evidence of centuries of use pervading every stone of it’s ancient walls. Dating from the 12th century, it has been in constant use with minor alteration ever since. It has seen the Catholic priest become Protestant parson through the Reformation, and weathered the societal changes and upheavals of the Civil War. It is an exemplar of an England that once was, and is yet, it’s presence providing a continuity in the face of the modernity of the world in which we live today. The immediate environment of this sheltered valley has changed little over the centuries, and would be recognisable today to peoples who lived here in centuries past. Generations of people were born, lived and died here, unknown now, their existence only marked by gravestones and fading records in the church register.

This church is small, simple and somewhat humble. It is mercifully unburdened with gothic excess, yet with the evidence of centuries of use pervading every stone of it’s ancient walls. Dating from the 12th century, it has been in constant use with minor alteration ever since. It has seen the Catholic priest become Protestant parson through the Reformation, and weathered the societal changes and upheavals of the Civil War. It is an exemplar of an England that once was, and is yet, it’s presence providing a continuity in the face of the modernity of the world in which we live today. The immediate environment of this sheltered valley has changed little over the centuries, and would be recognisable today to peoples who lived here in centuries past. Generations of people were born, lived and died here, unknown now, their existence only marked by gravestones and fading records in the church register.

I had visited this church on two occasions previously, and while I was much taken with it and it’s setting, my visits had been necessarily brief. When I had the opportunity to visit again earlier this year, I determined that I was going to photograph the place in a slow and casual manner. I had set aside a couple of hours to wander around a place which encompasses an area of about a quarter of an acre. There is little I enjoy more than slowly exploring a place in this manner. Walking this way and that, retracing my steps, and looking at a place from different perspectives. Standing and staring, watching the changing light as the clouds come and go. Such behaviour is a peculiarity it may be said, if not necessarily the preserve, of a photographer. It is something which I like to do alone. Not out of any sense of being unsociable, but for the sheer enjoyment of being left to my own devices and not having to concern myself with the wishes and imperatives of someone else.

I had visited this church on two occasions previously, and while I was much taken with it and it’s setting, my visits had been necessarily brief. When I had the opportunity to visit again earlier this year, I determined that I was going to photograph the place in a slow and casual manner. I had set aside a couple of hours to wander around a place which encompasses an area of about a quarter of an acre. There is little I enjoy more than slowly exploring a place in this manner. Walking this way and that, retracing my steps, and looking at a place from different perspectives. Standing and staring, watching the changing light as the clouds come and go. Such behaviour is a peculiarity it may be said, if not necessarily the preserve, of a photographer. It is something which I like to do alone. Not out of any sense of being unsociable, but for the sheer enjoyment of being left to my own devices and not having to concern myself with the wishes and imperatives of someone else.

I had decided to use my Minolta X300, a simple camera of which I’m particularly fond, coupled with a Rokkor 45mm f/2 lens, which I love for being that little bit wider than the more usual 50mm, and for the results it provides. Such a combination is the essence of the idea of keeping it simple. The Minolta X300 requires only that I chose my desired aperture, set the correct shutter speed, and focus properly. This combination is an ideal lightweight pairing for a relaxing photo walk, not that I’d be walking that far on this day. The only accessories I used were a yellow filter and a basic tripod for use whilst inside the church sanctuary. The film was Ilford FP4, which, along with Ilford Delta 100, are my favourite monochrome films.

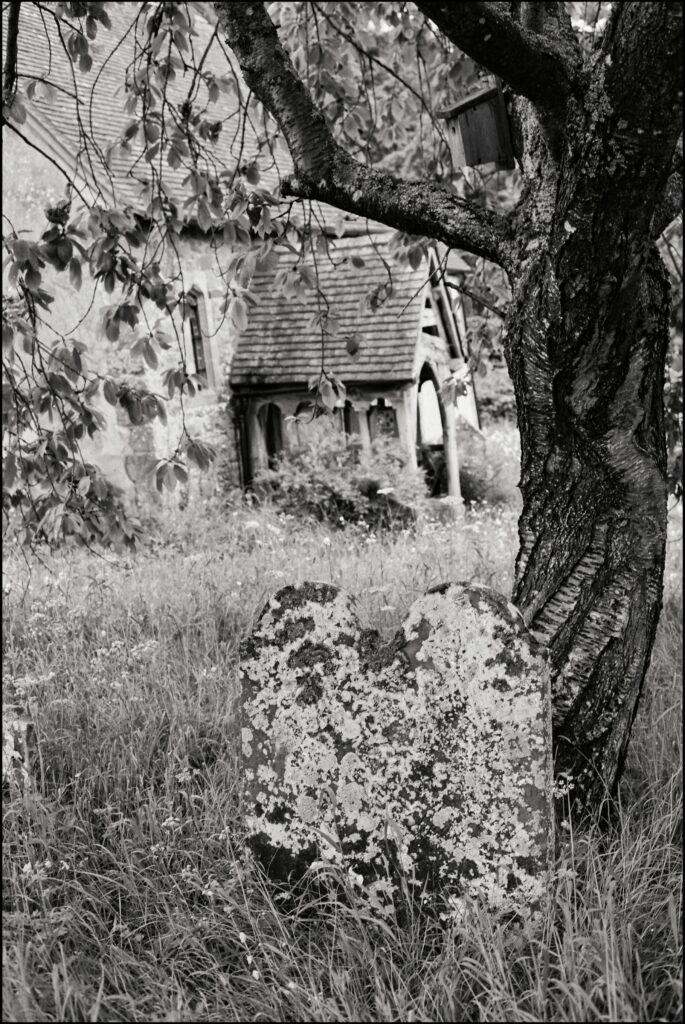

At first glance, the churchyard at St John the Baptist looks to be overgrown, however this is by design rather than neglect. It is maintained by an organisation called Caring for God’s Acre. They have a mission whereby they encourage the proliferation of wild flowers and grasses, cutting them in the autumn, in the manner which meadows were once tended in a time before silage and modern farming methods. I understand that they cut in the traditional manner using a scythe. These ancient churchyards provide little oases of wildness amongst the soil designated for agriculture.

Of course this is a boon for the photographer in search of the bucolic idyll, and the pathos of the overgrown and neglected. There had been rain prior to my arrival, and the trees and grass were gently dripping still. The sun was appearing and then disappearing between moving clouds, and the air was fresh after the rain, with the smell of the damp earth and herbage prevalent. My boots and the lower half of my trouser legs were soon wet and plastered with tiny seeds as I made my way through the grass which was knee height. It was one of those times when it felt good to be alive and alert to such elemental stimuli . Throughout my time there, the constant sound was the background hum of bees and other insects as they busied themselves amongst the wild flowers which grew in profusion. The sky seemed to be full of swifts and swallows, with the occasional buzzard or red kite and their plaintive calls. I couldn’t help but reflect on the poet William Butler Yeats and these lines from his poem The Lake Isle of Innisfree;

‘And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have peace there, for peace comes dropping slow.’

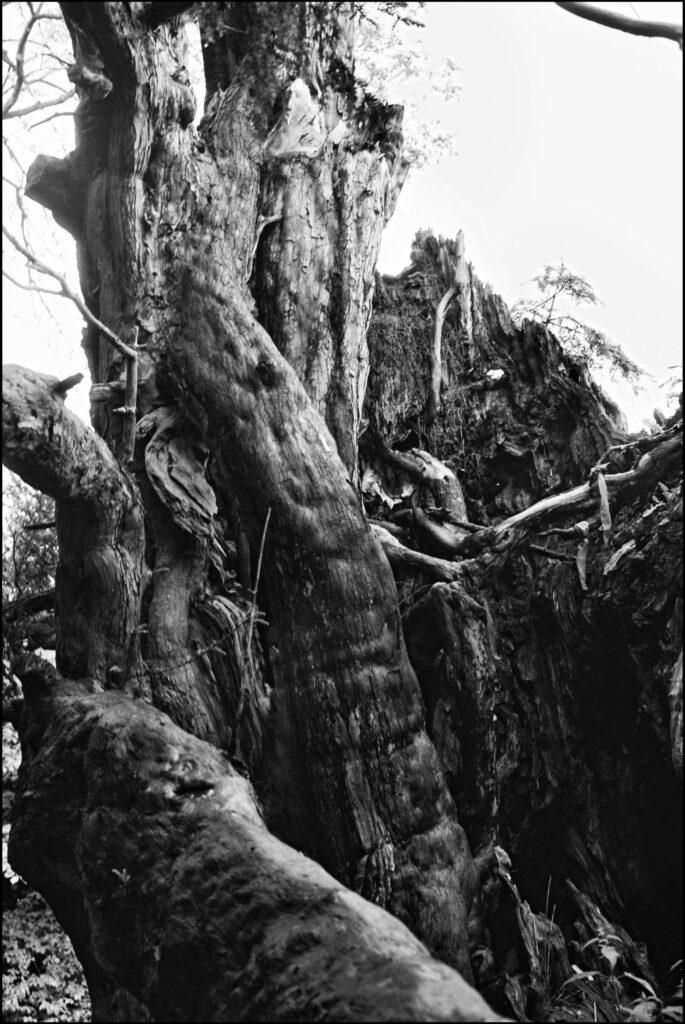

Within the churchyard, towards the back and surrounded by mature trees is a magnificent yew tree. It is reputed to be over a thousand years old. Yew trees are very much a characteristic of old churches throughout Britain, and many provided the wood for the longbows with which the archers fought in France in the medieval wars, and in the Middle East in the time of the Crusades . The example here had recently suffered damage during a storm, and has a shattered aspect with huge fallen boughs which had been piled up against and under the trunk. It reminded me of an old prize fighter, gnarled, battered and yet defiant.

Within the churchyard, towards the back and surrounded by mature trees is a magnificent yew tree. It is reputed to be over a thousand years old. Yew trees are very much a characteristic of old churches throughout Britain, and many provided the wood for the longbows with which the archers fought in France in the medieval wars, and in the Middle East in the time of the Crusades . The example here had recently suffered damage during a storm, and has a shattered aspect with huge fallen boughs which had been piled up against and under the trunk. It reminded me of an old prize fighter, gnarled, battered and yet defiant.

All the gravestones were covered in the subtle colours of the many varieties of lichen which give a camouflaged appearance and which has obscured many of the names which were carved into them. There are a pair of simple wooden gates which allowed access on foot to and from the road and some nearby fields. These gates had the shape and proportion of the work of an artist, with gently rising cross beams, diagonal reinforcing struts, and vertical slats finished with a spear point and a hole bored through the point. They were covered in the inevitable lichen, apart from where many hands had opened and closed them. They showed that their maker had taken time to craft them to be beautiful as well as practical, and age had rendered them more beautiful still. A rustic wooden bench under the shade of a mature hazel, was situated at the highest point within the churchyard, giving an opportunity to sit quietly and overlook the church and the surrounding valley.

Sitting on the bench, which was still slightly damp, I could view the majority of the ancient graves, bringing to mind a stanza from Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, by William Grey;

Beneath those rugged elms, that yew-tree’s shade,

Where heaves the turf in many mould’ring heap,

Each in his narrow cell for ever laid,

The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep.

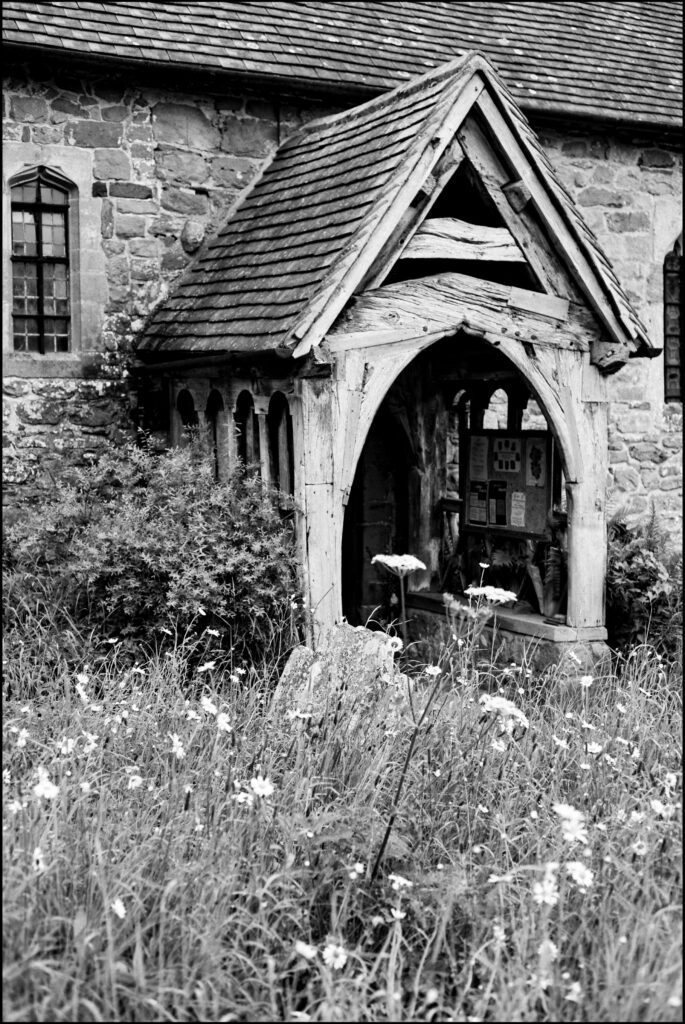

At the entrance to the church is the most wonderful oak porch. It has turned a beautiful silver grey, fissured with cracks and shakes and yet still standing proud, if ever so slightly askew. The mortice and tenon construction of the crucks and beams with their oak dowels show how this method of building allows for the variations in the weather and temperature, being able to swell and contract accordingly. It is roofed with hand cut stone tiles, and it was pleasing to the touch as well as to the eye.

At the entrance to the church is the most wonderful oak porch. It has turned a beautiful silver grey, fissured with cracks and shakes and yet still standing proud, if ever so slightly askew. The mortice and tenon construction of the crucks and beams with their oak dowels show how this method of building allows for the variations in the weather and temperature, being able to swell and contract accordingly. It is roofed with hand cut stone tiles, and it was pleasing to the touch as well as to the eye.

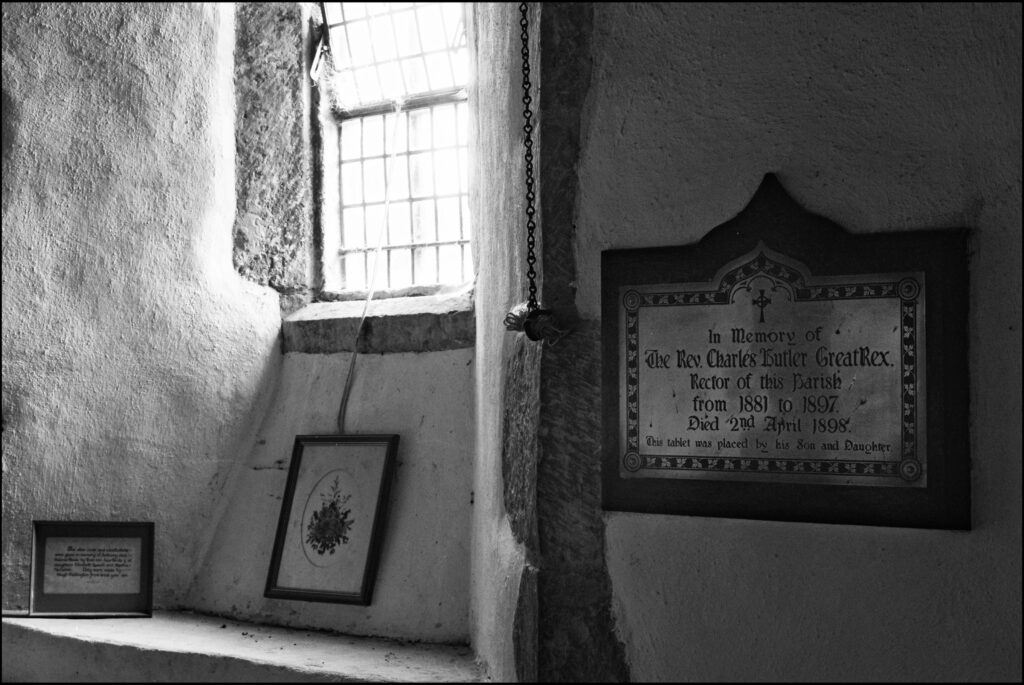

Entering the church via it’s venerable solid door, I passed into the stillness and silence that typifies ancient places of worship. The solidity of the stone walls, plastered and plainly painted, and the relatively small windows provided a coolness coupled with a filtered light. The alter, font and pulpit gave witness to the age of the church, yet there was no sense of this being a museum. The fresh flowers in vases, hand written parish notices and rotas for cleaning showed that this was a current place of worship which had meaning and importance to people. I took a number of images using the natural light, aided by the tripod. I set the camera to aperture priority, and used the self timer to fire the shutter. The Minolta’s light metering is good I have found, and gives a well balanced result in a place of contrasting shadows and light.

I returned outside of the church, the heavy thud and low metallic click of the door and it’s massive latch echoing behind me. There was a light breeze blowing and I felt pleasure of standing once more in the open. My home is in suburbia, north of where I was standing, and I reflected once again on the stillness mingled with soft noises which weren’t the sound of traffic and mankind. The light was beginning to gently fade as I walked back through the churchyard and out through the more modern, but still old lychgate and on to a narrow lane edged with high trees and dense undergrowth. Life was busy everywhere I looked. I had taken my many images, and thoroughly enjoyed the process. Another poet came to mind, a contemporary of Yeats by the name of William Henry Davies, who in his poem, Leisure, began and ended with the lines;

I returned outside of the church, the heavy thud and low metallic click of the door and it’s massive latch echoing behind me. There was a light breeze blowing and I felt pleasure of standing once more in the open. My home is in suburbia, north of where I was standing, and I reflected once again on the stillness mingled with soft noises which weren’t the sound of traffic and mankind. The light was beginning to gently fade as I walked back through the churchyard and out through the more modern, but still old lychgate and on to a narrow lane edged with high trees and dense undergrowth. Life was busy everywhere I looked. I had taken my many images, and thoroughly enjoyed the process. Another poet came to mind, a contemporary of Yeats by the name of William Henry Davies, who in his poem, Leisure, began and ended with the lines;

‘What is this life if, full of care,

We have no time to stop and stare,

…..

‘A poor life this if, full of care,

We have no time to stop and stare.’

My thoughts turned to that evening’s meal, of companionship and an eclectic library of books. Following a fine meal of roast chicken, I stood on the front porch at dusk, and looked out over the valley. With a smile to myself, I realised that it wasn’t all peace and solitude. The sheep were voluble, and cattle even more so. The nearby rookery was a cacophony of sound as the residents returned to their nests, whilst a neighbour’s Guineafowl seemed to take a screeching exception to my presence.

My thoughts turned to that evening’s meal, of companionship and an eclectic library of books. Following a fine meal of roast chicken, I stood on the front porch at dusk, and looked out over the valley. With a smile to myself, I realised that it wasn’t all peace and solitude. The sheep were voluble, and cattle even more so. The nearby rookery was a cacophony of sound as the residents returned to their nests, whilst a neighbour’s Guineafowl seemed to take a screeching exception to my presence.

While some of this narrative may seem to strike a note of melancholia, it was actually far from being such. The sheer life and vitality abundant in the churchyard meant it was impossible to feel such a negative emotion. The somewhat ironic fact that a place of burial was so teeming with life wasn’t lost on me. What I was left with was a sense of privilege at having had the opportunity to spend a couple of hours uninterrupted in a very extraordinary and yet apparently ordinary place. There are churches like this up and down the length of Britain, providing a refuge in the manner that they have always done. My overriding sensation was that of peace and contentment, with maybe just smallest sense of wistfulness that I was unlikely to ever be able to live in such a place as this.

So Mr Davies, I stood and I stared, and I agree with you wholeheartedly.

So Mr Davies, I stood and I stared, and I agree with you wholeheartedly.

Coda; All three of the poems I made reference to are in the public domain, and can be easily found online. All are wonderful, but ‘Elegy’ particularly so.

Coda; All three of the poems I made reference to are in the public domain, and can be easily found online. All are wonderful, but ‘Elegy’ particularly so.

Share this post:

Comments

Keith Drysdale on Elegy in a Country Churchyard

Comment posted: 05/10/2024