I recently took two tours that revealed different philosophies about how we look at the world around us. At the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, there are no title cards for the art on the walls. At the Woolworth Building in New York City, the guide scolded me for being too enthusiastic about taking photos without having listened to his explanation of the corbels and other features. I am not sure which is the better approach: to look at something as a subject for photography as simply that or to see it within a story. Perhaps as with much else, it simply depends.

The contrast prompts me to consider whether we need more than what the eye can see and the camera can document. At both destinations, I had my Contax G2, with a 45mm Zeiss Planar lens, loaded with Ilford HP5 set to ISO 1600, and a Lumix G8, with the 35-100mm (70-200mm FF equivalent) zoom. At each, I finished a roll of film, and I filled half an SD card. Although most of the frames are my excerpts of someone else’s art and architecture, a few contain people. The humans are the background rather than foreground. The places had in common the rich range of subject matter. Even someone willfully inattentive would feel sensory overload.

The irony, for a place that stands against the sharing of context in favor of a pure experience of seeing, is that the Barnes Foundation has its own engrossing backstory. A summary cannot do it justice. Albert Barnes was a physician turned businessman, who made his fortune on an eye treatment. He then became an art collector whose Parisian spending single-handedly set market prices for impressionists, post-impressionists, and early modernists. He believed it was possible to analyze his purchases objectively; for example, how was light treated, what were the lines, colors, spaces, textures, and so on. A friend of educational theorist John Dewey, Barnes opened the doors of his suburban facility in 1922 to teach his method, not as a conventional museum but as an educational institution — his employees were treated to daily seminars along the lines he had laid out.

Even today, the Barnes offers a certificate following its namesake’s curriculum, handed down strictly from generation to generation, as well as a single day session on “decoding” his ensembles, which include wall decorations and fireplace andirons interspersed among the canvases. Decades of litigation resulted in the original institution, associated with a historically black college, being moved downtown, at the insistence of civic leaders in the city of brotherly love. The new location duplicates the layout of the old location.

Yet consistent with Barnes’s wishes, you cannot discern from the usual placard anything about who created a work, the individual’s biography, or the social circumstances. The omission is deliberate. You are supposed to engage with the painting as a painting, in and of itself. It used to be that nothing could be loaned to other museums. It also was the rule that no photographs could be taken, then that only black and white reproductions were allowed. The enterprise having relented to contemporary demands, there is a digital archive available online for free. Photos are permitted, with the usual “no flash” constraint.

When I went, with a dear friend who earned a doctorate studying the Barnes, as well as the credentials bestowed by the place, the crowds were being led around by docents who delivered the narration the curious public expects. My shepherd was able to add the insights of the Barnes pedagogy. His arrangements were made according to principles. They have been preserved exactly. Some rooms have portraits who appear to stare across space at their counterparts indifferent to the crowd. They are silent, but they speak to one another — and thus to the spectator — and have for decades, such that inanimate representations can be imagined to have a life.

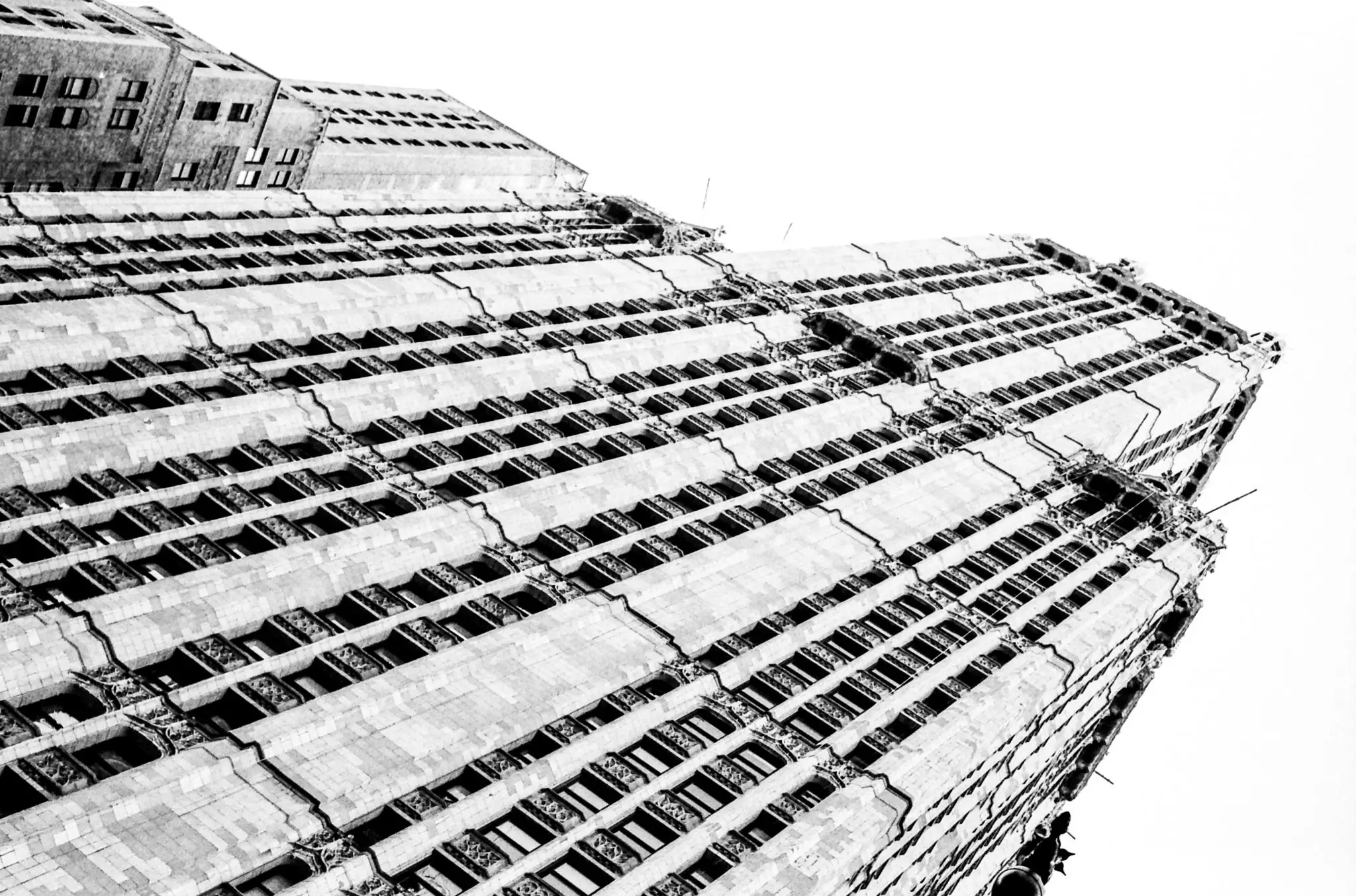

A Neo-Gothic “cathedral of commerce,” the Woolworth Building was once the tallest anywhere on the face of the globe, and it is still a sight worth seeing, as it is renovated to contain luxury condominiums. The “five and dime” department store, so-called because every item was available at one of those two price points, was once ubiquitous from coast to coast and on other continents that didn’t even have the same measures of currency, and Frank Woolworth, founder of the most famous chain of this type, made his fortune a penny at a time.

He put up his magnificent edifice between 1910 and 1913 on Broadway. Designed by Cass Gilbert, it was resplendent in white terra cotta over a steel skeleton, gleaming especially when President Woodrow Wilson ordered the light bulbs — then a luxury — be fired up for a grand opening dinner attended by, among others, Thomas Edison, who had to supervise the illumination ceremony. It has stayed in use. Woolworth himself occupied very few floors. He made additional profit as a landlord. Businesses continue to rent (though there was never a five and dime on the premises, since that was not quite appropriate for the high-rent district).

For the centenary celebration, tours were organized by the architect’s great-granddaughter. They proved so popular that they have become a regular feature, in multiple versions depending on how much time one would like to devote to admiring Tiffany elevators with an initial “W” on the frieze over each set of doors advertising, if anyone had forgotten for even a moment, who was responsible for entrepreneurial innovation well before Wal-Mart and Amazon. Review websites accord the tours the highest ratings. There probably are few if any excursions within a skyscraper, right down to the basement that had entrances to the subway and a German beer hall back in the day, that cover as much detail. Anyone with the least interest in such matters would be educated and entertained.

I learned a new word, for example: corbel, a decorative piece tucked within the interstices of wall and ceiling, helping support the structure. The corbels — to be distinguished from gargoyles — here are caricatures of a dozen individuals associated with the enterprise, from the construction supervisor to the property manager to the financier to Woolworth himself. A few figures also are “inside jokes,” some of which are obscure, others of which are easy to figure out, such as George Washington. I enjoyed the spectacle, and my pleasure was enhanced, as it is for those of us who carry around a camera, by the opportunity to record the memory. I took no offense at being chastised for my obsessive snapping of the shutter — apparently there was a special tour option labeled as emphasizing photography. The suggestion it would be useful to have information about what I was focusing on made me wonder whether that is so. (There is another issue, of course, of whether using a camera while interacting with others who are not posing for their picture is rude.)

The afternoons at the Barnes and the Woolworth were worthwhile. There was such a contrast between these two episodes. I want to lead a life in which I learn constantly. My mind is constantly hungry for more data.

Nonetheless, I am not sure which was more meaningful for me as a photographer, or which generated the photos that are more significant for an observer, who is further removed. Other than abstractions, there is the reality, then the art, finally the photo (and, as a supplement, this writing). Or perhaps the art and the photo each can be regarded in its own right, without reference to the reality. Photography is part of how we process the world. There is much to be seen; there is much to be read.

Share this post:

Comments

Kara Woodward on Do We Need to Know What We’re Looking At? – By Frank H. Wu

Comment posted: 10/01/2019