In early 2019, my interest in analogue photography was suddenly rekindled after a hiatus of a mere 35 years – as a teenager I had discovered my grandfather’s 6×6 folder and learnt photography using this 1940s camera, shooting in B&W and having prints made at the local photo shop. Alas, few of those pictures have survived my adult years. Thinking about it, it might actually be a good thing. You don’t know what I got up to back then!

I think that in the past couple of years I had got sick of taking thousands and thousands of digital photographs and relegating them to the confines of various external hard drives, some of which I can’t even access any longer due to their obsolete Firewire format. I wanted to make my snapshots count again, so I set out acquiring a small, yet comprehensive collection of cameras, helped by the fact that many classic cameras can be had for a song these days. The loot included a Contax IIa, a Rolleicord, an early Pentax Spotmatic and a Canon F1 (original), amongst others, as well as, most recently, a Rolleiflex SL35. (I’ve also set up a complete B&W darkroom, as I want to go the whole way in terms of “artistic control” – the images for this articles are, without exception, scanned from either RC or fibre-based prints.)

My version of the Rolleiflex SL35 is an early model, made in Singapore, without the complex electronics featured in later models such as the SL35 ME that gave the series a bad reputation due to reliability issues. The SL35 had been made in Germany for a couple of years after its release in 1970, but Rollei moved production to Singapore owing to the financial pressures incurred by having to compete in the crowded SLR market, led by Far Easterners Nikon and Canon. The German-made model is rather more collectible, although arguably identical to its immediate successor.

When the SL35 was released it was already an anachronism. While it had been designed completely from scratch (Rollei had little to no experience in the SLR field), technologically it was a throwback to at least a decade before – unlike its Japanese contemporaries, it had no open-aperture metering, only an old-fashioned TTL meter, neither was it a true professional “system” camera. It didn’t even come with a hot shoe! On the upside, a large number of top-quality lenses were made available in Rollei’s proprietary QBM bayonet mount, from the likes of Carl Zeiss and Schneider Kreuznach, as well as the cheaper Rolleinar lenses manufactured for Rollei by Mamiya. The normal lens supplied with the SL35 was the Carl-Zeiss-made f1.8/50mm Planar, which is the one that came with my Rollei.

Feature-wise the SL35 is nothing to write home about – one could say its feature set and layout were borrowed wholesale from Asahi Pentax’ early 1960s Spotmatic, with one odd exception: Where one would expect to find the shutter release on an SLR camera, there is a big black plastic button that triggers the TTL metering system. The shutter release is mounted on top of the combined shutter speed/film speed thumbwheel which lives in the usual place further towards the viewfinder. In practice, however, this has not posed a problem to me for very long. The lens can be switched from manual (M) to auto (A), with the latter setting allowing the user to meter with the chosen aperture value engaged. I tend to use the manual setting, since focussing through a dimmed-down lens is rather inconvenient. As I tend to use either Sunny 16 or an external light meter, the camera’s integrated metering system is a bonus for me at most.

In terms of handling, the SL35 compares favourable with my Pentax Spotmatic. It is surprisingly small and lightweight for a pro-level SLR, but feels very solidly built indeed. Shutter speeds range from B to 1000; ISO settings reach a whopping (for its time) 6400. The minimum focussing distance of the Planar lens is 0.45 m or just under 1.5 ft. The viewfinder is pretty bright, but not exceptionally so, with a grid imprinted into the glass for help with composition – a nice Rollei touch! The simplistic needle-match light meter does what it says on the tin, provided the correct 1.35v battery (hack) is inserted. The SL35 is fully mechanical, unlike its later versions; the battery is only required for powering the meter.

Its perfect handleability (if that’s a word) as well as the excellent Carl Zeiss Planar 50-millimeter lens with a maximum aperture of f/1.8 are what could easily make this camera my new favourite. The Planar renders images with very good sharpness, yet not clinically so. It has a lot of character at the same time, probably owing to its super-vintage heritage. The Planar was originally developed by Paul Rudolph for Carl Zeiss in 1896! Since I am mostly a nifty-fifty shooter, this lens doesn’t leave me wanting for much at all.

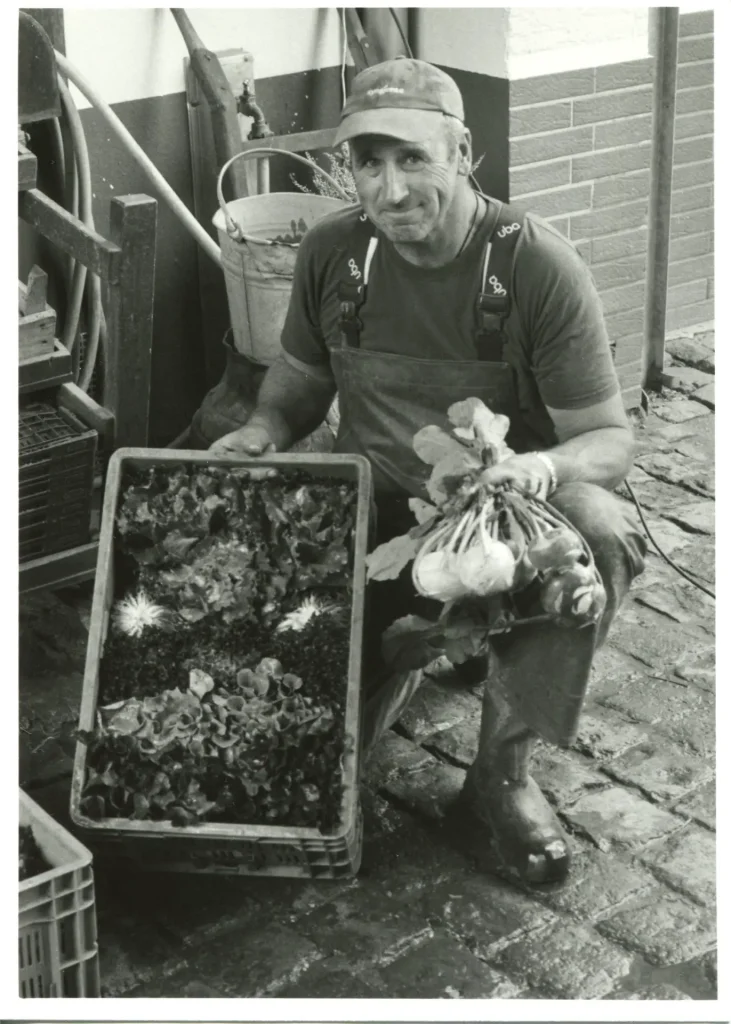

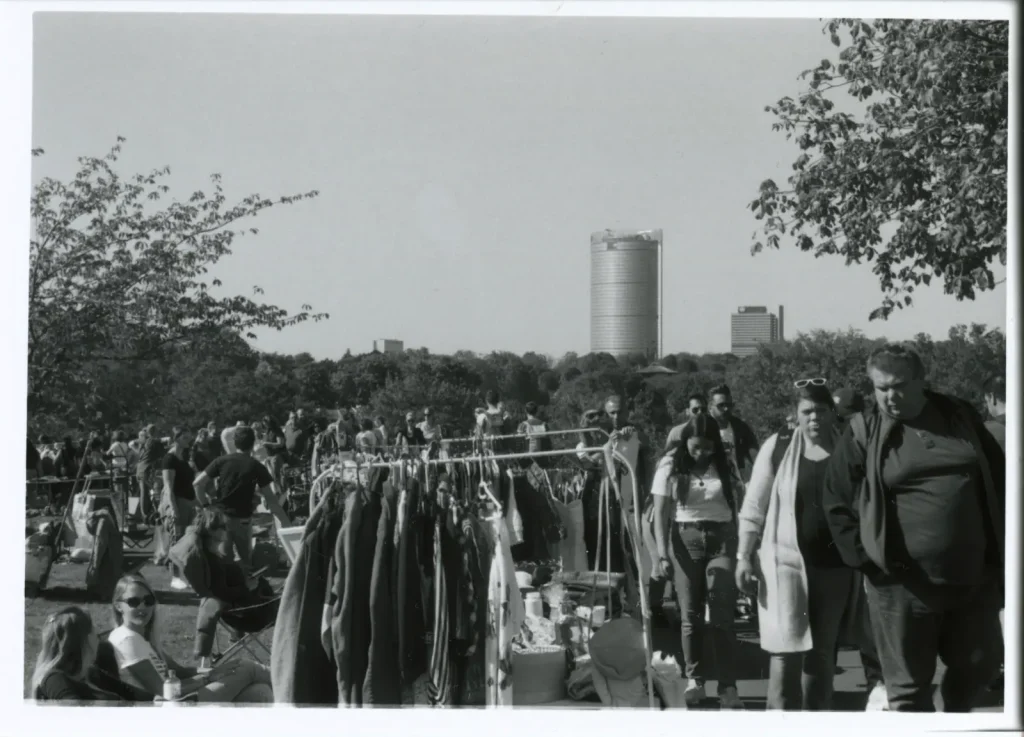

One major factor that has drawn me back into film photography is the somewhat stark look of the shots published by photojournalists and documentary photographers of the “Golden Era” from the 1940s to the 1970s. Ever since I started shooting film again, I have been on a mission to emulate that look, sometimes more, sometimes less successfully. I have interviewed old-timers about their photographic and darkroom work and have spent a lot of time experimenting in the darkroom myself.

However, that’s a topic for a whole other article. Suffice it to say that I gravitate towards the nicely old-fashioned Fomapan 100 and 400 emulsions which, despite what is propagated in many forums, look great even if pushed a couple of stops. These five frames were shot recently on Fomapan 100, some at box speed, dev’ed in Rodinal, others pushed to 200 and dev’ed in Atomal 49. They were printed on Foma RC or fibre-based papers at grade 2, i.e. neutral contrast. Therefore, all the contrast you see is from a combination of the Planar lens and the push development, where indicated.

If you have read this far, please accept my gratitude for sticking it out this long for my first ever piece on film photography!

Some of Recky’s images can be found on Instagram at @reckys_film_lab. As he prefers scanning prints rather than negatives, things evolve at a relatively slow pace.

Share this post:

Comments

Peter Grey on Rolleiflex SL35 mini-review- A Gorgeous Under-The-Radar SLR – By Recky Reck.

Comment posted: 08/11/2019

Comment posted: 08/11/2019

James Evidon on Rolleiflex SL35 mini-review- A Gorgeous Under-The-Radar SLR – By Recky Reck.

Comment posted: 08/11/2019

Comment posted: 08/11/2019

Dan Castelli on Rolleiflex SL35 mini-review- A Gorgeous Under-The-Radar SLR – By Recky Reck.

Comment posted: 09/11/2019

The 'old timers' loved the Rolleiflex as a fine piece of photo equipment. It shared shelf space w/Nikons, Leicas, Hasselblads, Rollei TLR's and large format gear. That was the heady group it hung out with. You've got a good piece of equipment.

One of the best comments from your article: (I’ve also set up a complete B&W darkroom, as I want to go the whole way in terms of “artistic control” – ) YES! I never gave up the darkroom. I call artistic control "the process."

I wish you continued success with the Rolleiflex and your darkroom.

Comment posted: 09/11/2019

Comment posted: 09/11/2019

Comment posted: 09/11/2019

Chris Gordon on Rolleiflex SL35 mini-review- A Gorgeous Under-The-Radar SLR – By Recky Reck.

Comment posted: 02/04/2020

Ibraar Hussain on Rolleiflex SL35 mini-review- A Gorgeous Under-The-Radar SLR – By Recky Reck.

Comment posted: 20/02/2023

I used to have a couple and sold them

Wrote a review on Steve huff site many years ago

https://www.stevehuffphoto.com/2012/09/03/film-the-west-german-rolleiflex-sl35-by-ibraar-hussain/

Since then I had another but ultimately sold it too as I found the Contax cameras and lenses to be so much better

Lyle Farmer on Rolleiflex SL35 mini-review- A Gorgeous Under-The-Radar SLR – By Recky Reck.

Comment posted: 07/07/2023

0

0

0