Regular readers of 35mmc know that I like to photograph urban (and rural) decay. Last December (2019), quite by chance, I found a treasure in Jackson, Mississippi. In the southeast part of town, which was formerly industrial, I saw a car at the old Morris Ice Company warehouse at 652 South Commerce Street. Next to the building, an old electric pump partly smothered with vines called out to be photographed. A young gent came by, looked at my Hasselblad camera with interest, and said he had recently bought the building along with four acres of land from the heirs of the Morris family.

I asked the proprietor if I could take some pictures inside, and he generously said I was free to take pictures for about a half hour. A movie group was already inside and had set up lights with colored gels. Someone was going to pose with grandma Morris’s 1962 Cadillac, which looked pretty good except for flat tyres. My favorite Panatomic-X film was in the film back of my Hasselblad 501CM. Being a slow film, most of my exposures inside were 1 sec at ƒ/5.6, but one exposure was 20 seconds. One of the cinematographers also admired my Hasselblad.

Ice Industry Background

During the mid-late 1800s, the ice trade was a major industry for many of the northern states of the USA. In winter, workmen sawed blocks of ice from frozen lakes and rivers. They stored the ice in specially constructed ice houses using sawdust for insulation. Led by the New England states, ice companies shipped ice around the world, sometimes as far as South America and even India. American ice was renowned for its purity. In the mid-West, ice companies shipped block ice from the Great Lakes and smaller bodies of water down the Mississippi River to St. Louis, Memphis, Baton Rouge, New Orleans, and innumerable smaller towns.

In the Civil War, the union armies used ice to reduce fever of wounded soldiers. After the war, cattle companies depended on ice to ship beef to stock-houses in Chicago and to ship finished meat products to eastern cities and even across the Atlantic Ocean to Great Britain. The major problem with block ice cut from frozen lakes was loss from melting, despite the best attempts at storage and insulation. By the 1880s, refrigeration machinery finally became reliable and capable of manufacturing bulk ice. Many southern cities installed ice plants because of the unreliability of natural ice in late summer. In the early years of the 20th century, refrigeration cooling systems and commercial ice plants rapidly supplanted the natural ice trade.

A Civil War veteran originally founded the Morris Ice Company in 1880. The original company sold ice that had been shipped down the Mississippi River from northern states but sometime around the turn of the century, began to manufacture ice. The ice factory at S. Commerce Street was in operation from the 1920s to 1988, during which it became one of the largest ice distributors in Mississippi. According to an article “Making Ice in Mississippi” by Elli Morris (the great-granddaughter of the founder):

“With the advent of inexpensive manufactured block ice, new businesses could operate year round in Mississippi, while others moved to the state for the first time. Dairy farming, concrete production, chicken processing plants, bakeries, and florists are a few types of industries that prospered using manufactured block ice. Two industries in particular, farm produce and seafood, grew hand-in-hand with the rise of manufactured block ice.”

In 1988, Mr. Morris sold his business to another Mississippi-based ice company. I do not know how long the factory on S. Commerce Street remained in production after that.

Interior Photographs

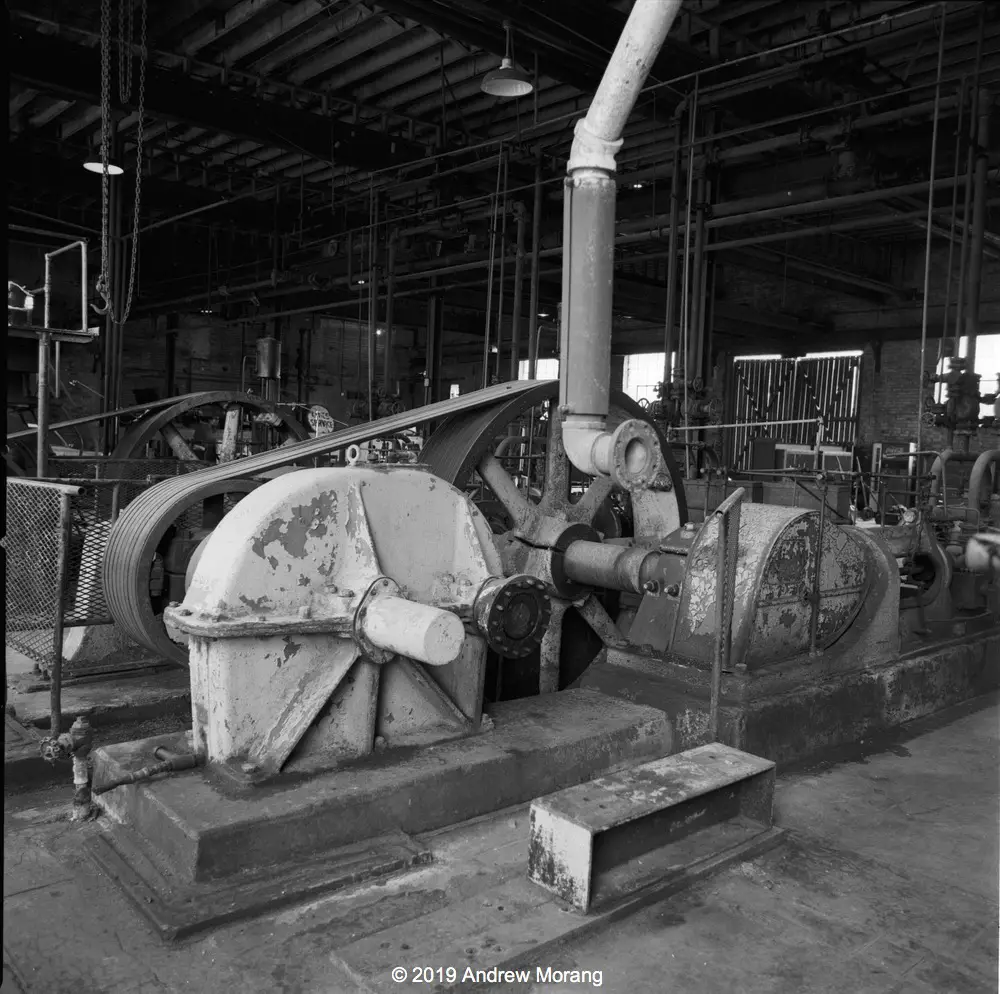

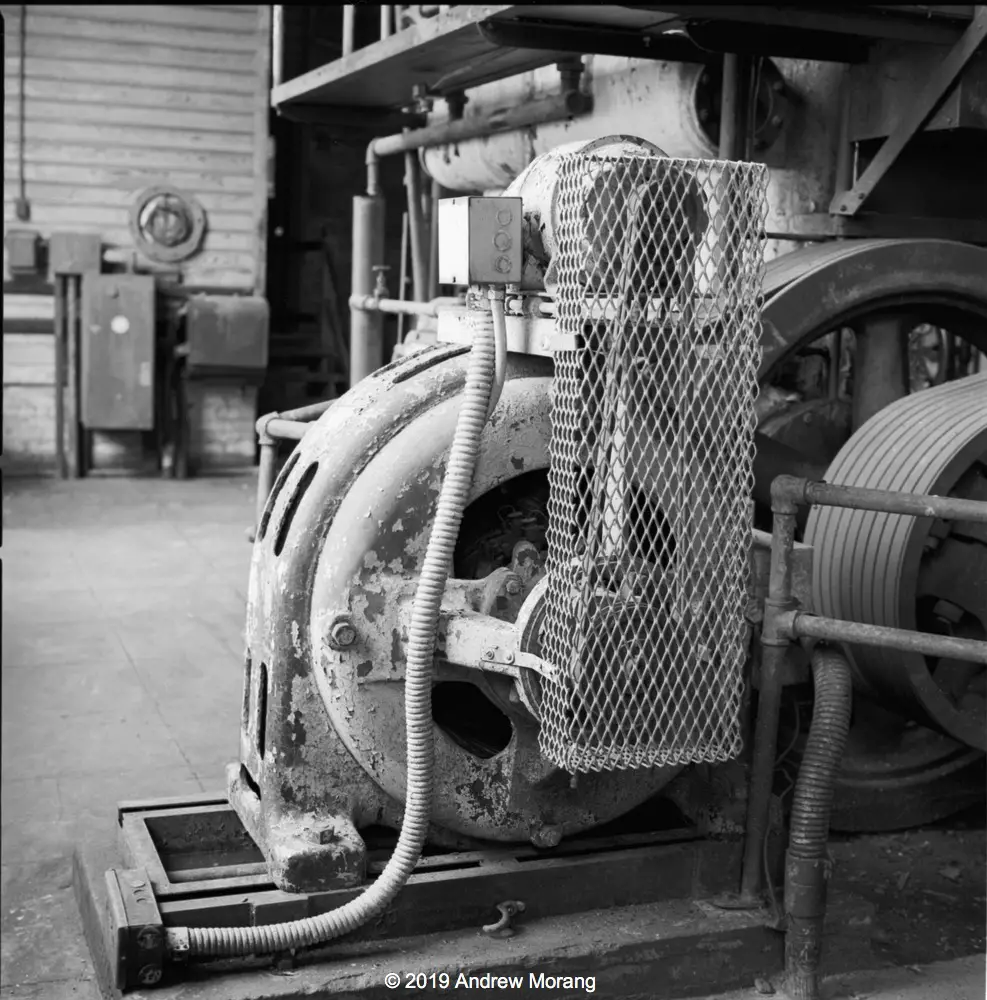

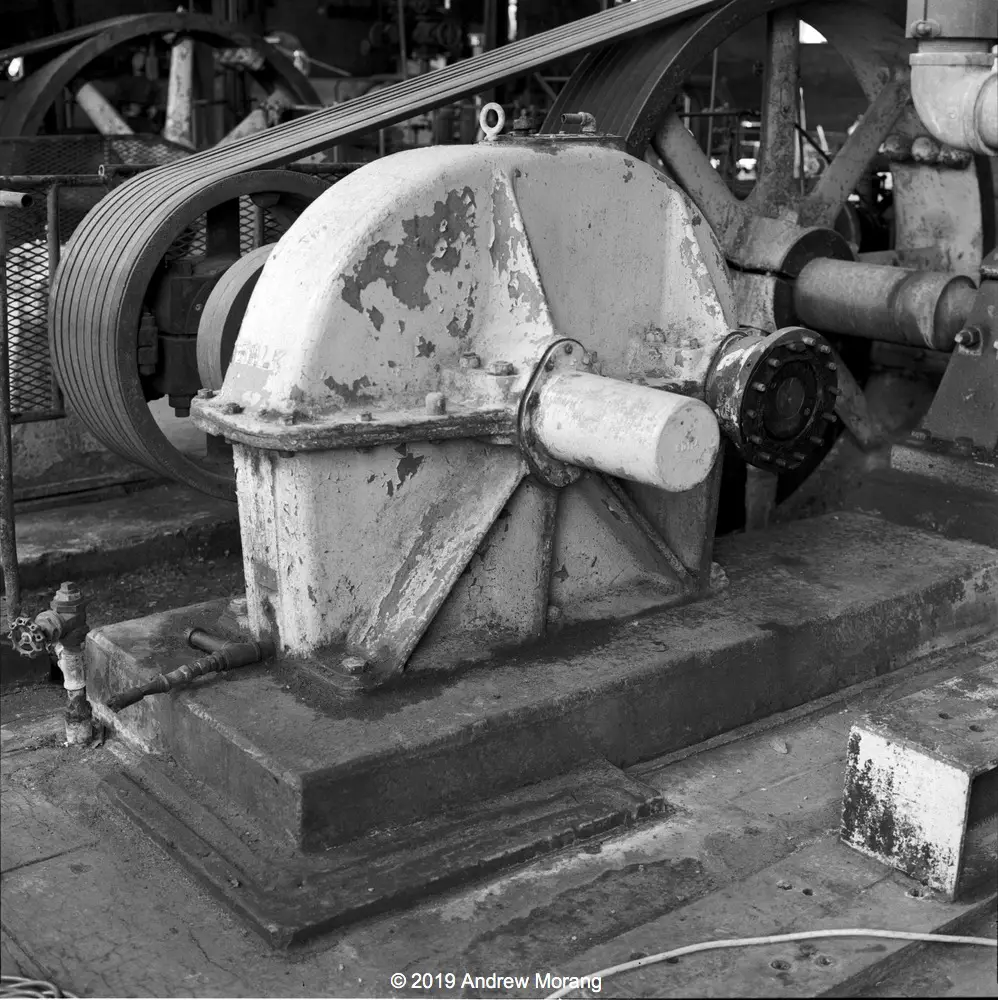

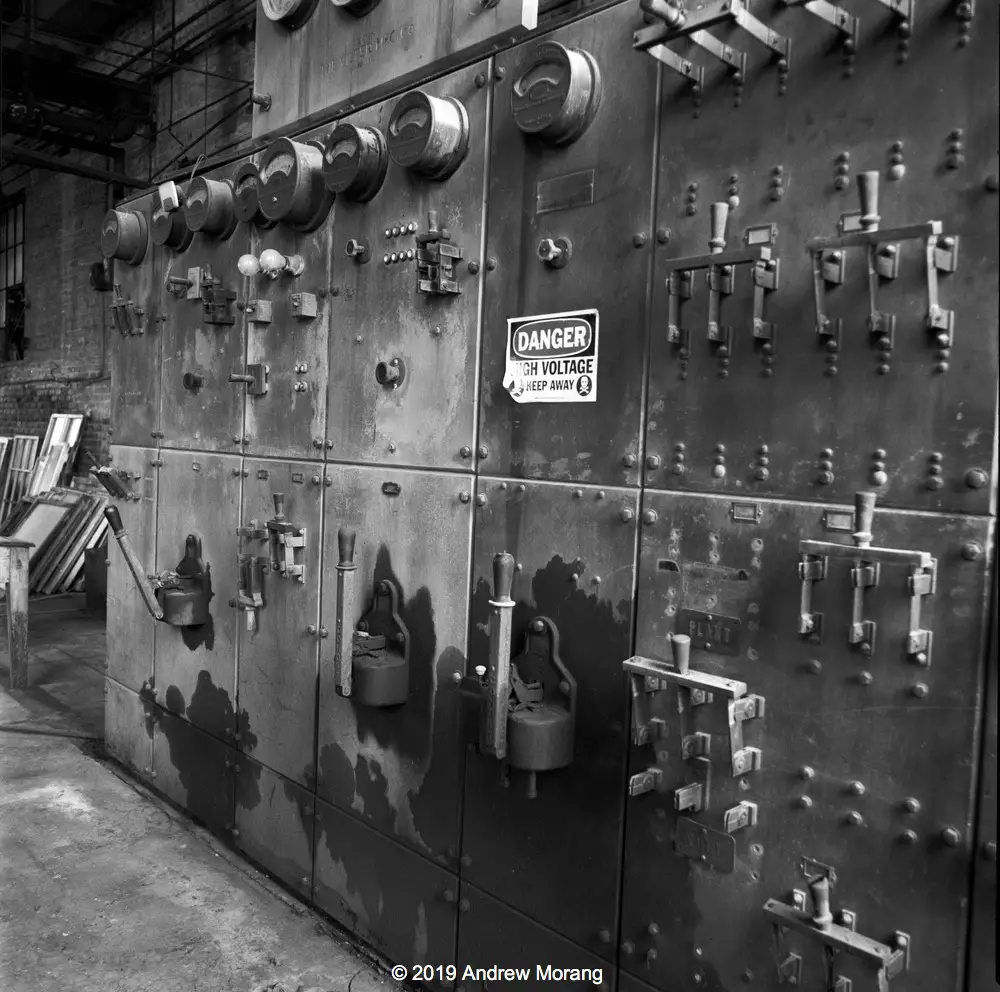

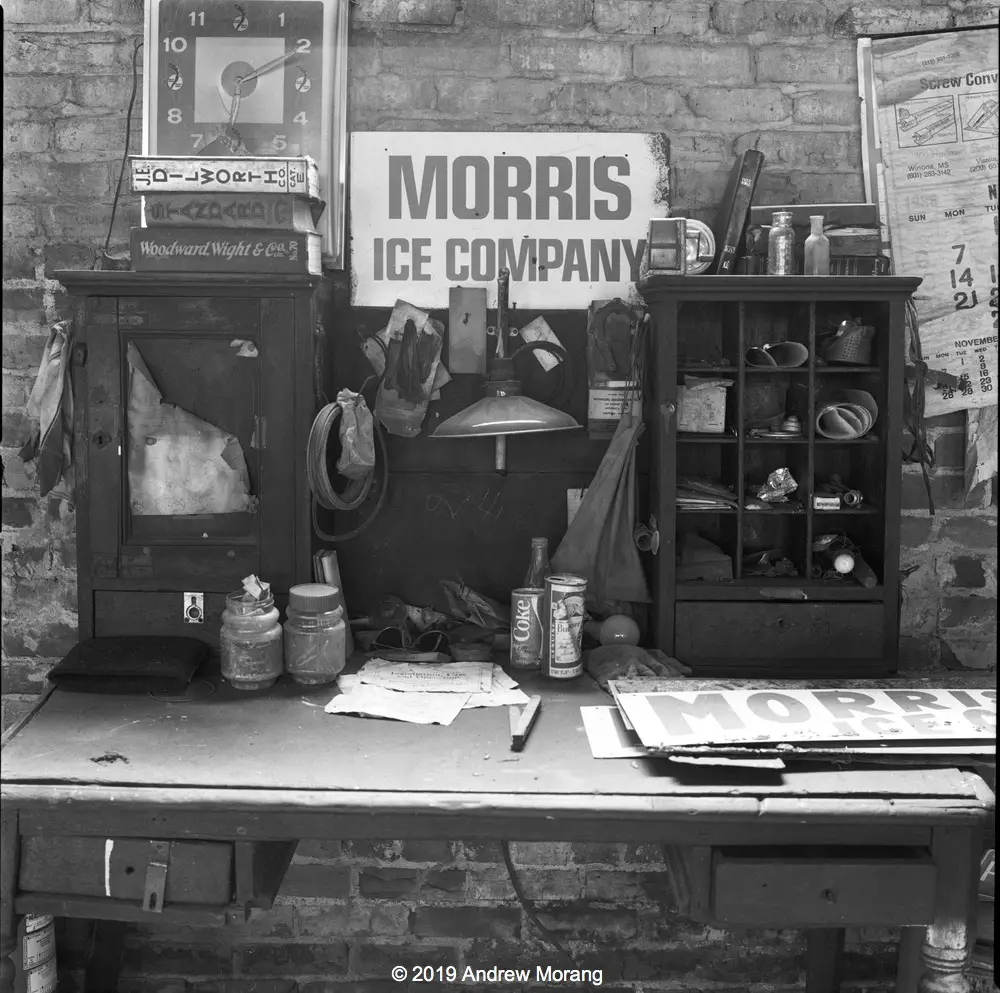

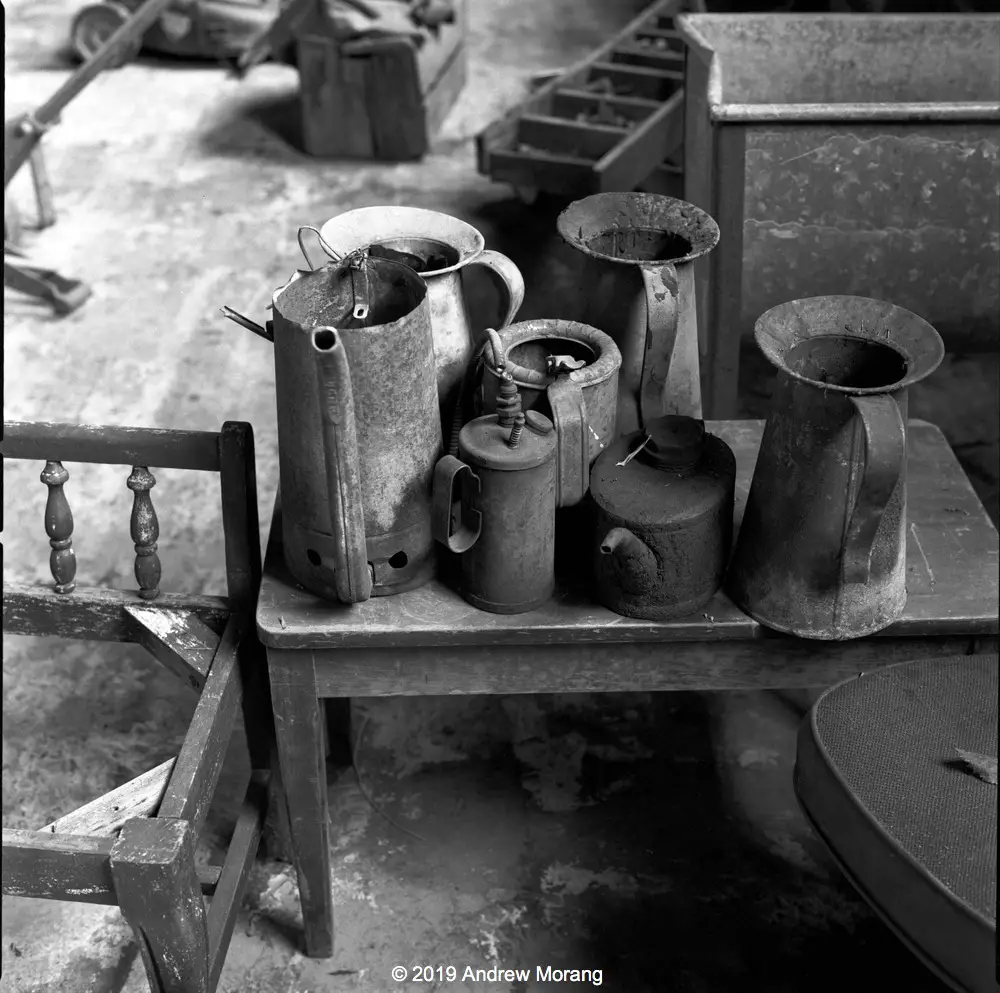

The inside of the Morris Ice Company is a amazing time capsule of early 20th century machinery. It is a spectacular setting of tubes, big machines, belts, tools, old shelves, chipping lead paint, and low-angle lighting.

These belt-driven compressors were for an ammonia cycle, where chilled ammonia circulated through pipes in salt water tanks. Rectangle steel molds made 300-lb ice blocks 1-foot thick and 4-feet tall. Trolleys ran on rails along the rafters to carry the ice blocks to waiting rail cars or trucks. Unfortunately, I did not see any of the trolleys and assume they have been removed. Railroad tracks still run down these streets but are no longer usable.

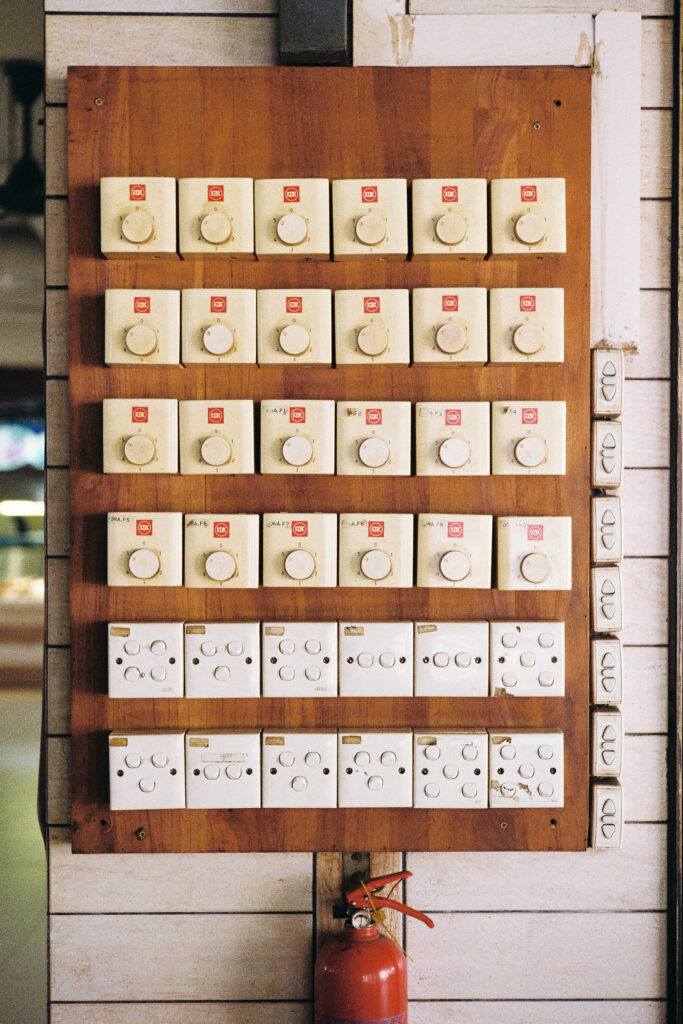

The Morris company had its own electricity plant and during its early years sold excess electricity the City of Jackson. The electric pump outside (see photograph no. 2) was for the former well, which tapped an aquifer 600 ft below. All the levers with their bakelite handles and fuses on the electric control panel were mounted on slate panels. This had been a totally manual, old-fashioned operation. I thought it was amazing that the electrical panel had survived the decades.

This large old diesel engine would turn a pulley. Some of the compressors were turned by electric motors, but possibly this was a backup in case the electrical power failed.

The desk contained time booklets for all employees back to the 1960s. There was no computer technology here.

This is a collection of oil cans from the old days. I am sure there was a significant oil consumption keeping the many bearings lubricated.

When the movie crew started, we walked outside and around to the back lot to meet a photographer. This gent lives in a garage apartment. He also commented on the Hasselblad. He said he had just given the new owner of the site one of his Nikkormat cameras and was going to teach him how to do film photography. I told them my first serious camera was a Nikkormat that I bought in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The photographer said he knew the place because he graduated from Boston University in the late 1960s. Come to find out, we both used to visit the same camera stores in Harvard Square back in the day. He also used Panatomic-X years ago. Small world.

All photographs except the first are medium format Panatomic-X film from a Hasselblad 501CM camera. As I noted above, most were 1 or ½ sec. exposures, and I used a tripod to stabilize the camera for all photographs. I specifically scanned at low contrast to show all the texture and detail of the machines. When the virus restrictions are finally over, I will ask Mr. Pickering (the owner) if I can return with my 4×5″ camera and record some more of the textures and patterns. I might even try one of my 1960s GAF film packs.

Thank you for riding along the Urban Decay train. You can see more of my explorations at https://worldofdecay.blogspot.com.

Share this post:

Comments

Peter on Exploring an Ice Factory in Mississippi with Panatomic-X Film in a Hasselblad – by Andrew Morang

Comment posted: 09/11/2020

Ken Rowin on Exploring an Ice Factory in Mississippi with Panatomic-X Film in a Hasselblad – by Andrew Morang

Comment posted: 09/11/2020

Comment posted: 09/11/2020

Castelli Daniel on Exploring an Ice Factory in Mississippi with Panatomic-X Film in a Hasselblad – by Andrew Morang

Comment posted: 10/11/2020

BTW, are you familiar with the work of the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER?) look for a book titled “Industrial Eye” by Jet Lowe. Your work bears a strong resemblance to his industrial photography done for HAER. It’s a program connected to the Library of Congress. You might find it interesting.

I really look forward to your postings; always good photos and insightful back stories.

Comment posted: 10/11/2020

Christian Schroeder on Exploring an Ice Factory in Mississippi with Panatomic-X Film in a Hasselblad – by Andrew Morang

Comment posted: 11/11/2020

Comment posted: 11/11/2020

Scott Gitlin on Exploring an Ice Factory in Mississippi with Panatomic-X Film in a Hasselblad – by Andrew Morang

Comment posted: 11/11/2020

Comment posted: 11/11/2020

Michael Bresler on Exploring an Ice Factory in Mississippi with Panatomic-X Film in a Hasselblad – by Andrew Morang

Comment posted: 12/11/2020

Aloy Anderson on Exploring an Ice Factory in Mississippi with Panatomic-X Film in a Hasselblad – by Andrew Morang

Comment posted: 15/11/2020

Comment posted: 15/11/2020