About a year ago, some Austrian friends handed me a Zeiss Ikon Contaflex Super B that they brought with them to America after World War II. They said it no longer worked, and if I got it going again, I could keep it.

Anyone who’s ever held a Contaflex knows it’s a gorgeous— but heavy– little machine. It’s also so complicated that most repair shops won’t touch one today. So… hey… why not take a stab myself? What could possibly go wrong?

Actually, nothing… I got off easy on this one!

Oh Nooooooooo…Fungus!

I first burned a roll of Fujicolor 200 to test the camera and its Pro-Tessar 35mm f/3.2, 50mm f/2.8, and 115mm f/4 “supplementary” lenses.

NOTE: They may look and feel like “real” lenses, but these “supplementaries” are lens elements that bayonet-mount in front of additional elements that are built into the camera. This approach let Zeiss create a between-the-lens leaf-shuttered SLR. But the split-lens design also makes it effectively impossible to adapt Contaflex “lenses” for use on today’s digital cameras.

Sadly, the 35mm “front element” had languished for years in a humid Florida basement… and suffered from serious fungus:

And the fungus could infect other cameras that came anywhere near it. So I’ve put the 35mm element into isolation until I figure out how to disassemble and clean it (a procedure that isn’t at all obvious). If it turns out that I can’t, I’ll reluctantly trash it. But even if I succeed, its internal elements may be so badly etched that they’ll never again achieve sharp focus. (I’d keep it, though, as an artistic soft-focus element.) Fortunately, the camera– and its 50mm and 115mm fronts– didn’t suffer the same fate.

A Strange Test Roll

I brought my test roll to Walgreens (along with a roll from a Yashica T4 yard-sale find). It had been a while since I’d used drugstore developing, and I assumed that I’d get negatives in return. Foolish me. The drugstore’s laboratoire du jour sent back a Photo CD of scans.

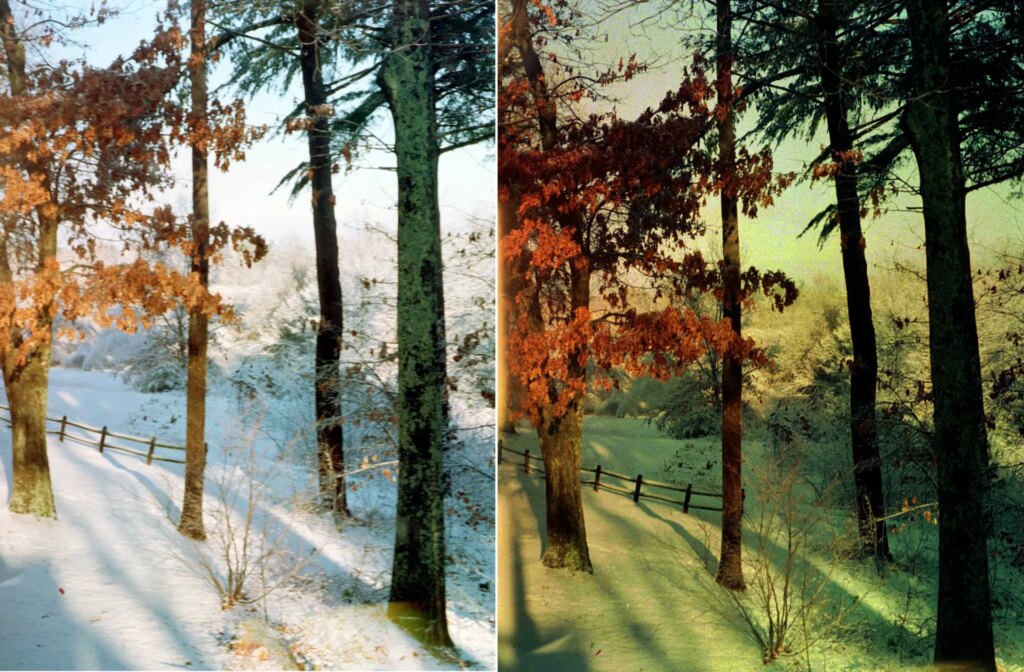

The Yashica photos were beautiful (I’ll write about them too). But the Contaflex images were so strange, that I doubted the lab was responsible. Over and over, one shot would look great, while the very next frame (taken of the same view immediately after the first) was surreal. Like this pair:

If that had happened with a digital camera, I’d throw it out. But the Contaflex is a jewel-like marvel, and I decided to examine it more closely.

Some Surprising Engineering

Removing the 50mm element from the bayonet mount revealed an element behind it in the camera’s throat:

Unscrewing the conical cowling and its attached glass, I could see five shutter blades poking slightly into the cavity in front of yet another element:

I watched this shutter through several activations, and every time I wound on and pressed the shutter button, the blades didn’t move. But every time, a second set of blades (hidden behind these frozen ones) quickly closed down and then popped back open. But they never closed completely.

It was a surprise, and I surmised that the moving blades were the camera’s aperture iris— which fully opens for focusing, and quickly snaps back to the preset aperture for exposing film. It participates in a complex mechanical ballet with the frozen shutter and a reflex mirror in the film chamber (as described as follows on this web page):

“When the Contaflex SLR takes a picture, a number of things have to happen perfectly. The shutter must close before the mirror swings up. Then the aperture must close before the shutter opens and then the shutter must open and close. There are a large number of very precise complex parts provided to accomplish all of this complex synchronization.”

And the nonfunctional shutter must therefore control exposure times. But since it’s currently frozen open and the aperture iris never fully closes, the film behind them was probably being “flashed” by incoming light. The extent of this flashing would vary with the preset aperture, and I think this might have caused the bizarre coloration of the camera’s alternating shots. (Not sure how that would actually work, but it’s my theory for now.)

And a Surprisingly Easy Fix!

Then, to see if anything would happen, I very gently touched one of the frozen shutter blades with a toothpick… and all five blades briskly snapped shut. Dust may have actually locked them open for years! And when I shot a second roll, the camera behaved itself nicely:

Epilogue

I told our Austrian friends that as far as I knew, their Contaflex was working again (though its meter may not be accurate). I also offered to return it. After all, they had given the camera to themselves as a gift– after surviving Nazi refugee camps during the war. But they graciously declined to take the camera back, and wished me happy days with it.

Sometimes, a camera’s story is greater than the device itself. I’ll continue to use their lovely Contaflex until it– or I– pass on. It wouldn’t feel right to do otherwise.

FINAL NOTE: I did not process the Contaflex photos beyond slight cropping.

Share this post:

Comments

Terry B on Fixing an Ailing Zeiss Ikon Contaflex Super B SLR – By Dave Powell

Comment posted: 09/11/2022

Your camera was made from 1962/3 so whilst a nice story, the 17 years since the end of WWII seems to me to be just a little long for the association that it was brought to America after WWII.

Comment posted: 09/11/2022

Comment posted: 09/11/2022

Tim Bradshaw on Fixing an Ailing Zeiss Ikon Contaflex Super B SLR – By Dave Powell

Comment posted: 09/11/2022

The reason I think this is that if the shutter was not closing the only thing protecting the film from the light is the mirror. And the mirror on those cameras stays up until you cock the shutter next time. So unless there is some secondary focal-plane shutter which I don't think there is (but its possible, given the rather heroic engineering of these things), then once it's up, and if the shutter doesn't close, the film is seeing light until you cock the shutter again, which is probably at least several tenths of a second: you'd get pictures which were catastrophically overexposed.

Much more likely is that it was just really sticky, I think, although the exposure mechanism of these things must be pretty hairy (shutter-priority automatic exposure ... with no battery), so I'm not sure.

In any case this was really interesting, and these are lovely cameras though I've never really got on eith mine (too big, I think).

Comment posted: 09/11/2022

Comment posted: 09/11/2022

Comment posted: 09/11/2022

Comment posted: 09/11/2022

Comment posted: 09/11/2022

Comment posted: 09/11/2022

Jens on Fixing an Ailing Zeiss Ikon Contaflex Super B SLR – By Dave Powell

Comment posted: 09/11/2022

Alone, the Carl Zeiss Tessar 50mm is able to produce marvellous pics, both with b&w or coloured film.

Comment posted: 09/11/2022

Dan Castelli on Fixing an Ailing Zeiss Ikon Contaflex Super B SLR – By Dave Powell

Comment posted: 10/11/2022

Comment posted: 10/11/2022

Gil Aegerter on Fixing an Ailing Zeiss Ikon Contaflex Super B SLR – By Dave Powell

Comment posted: 14/11/2022

Comment posted: 14/11/2022

Fixing an Ailing Zeiss Ikon Contaflex Super B SLR – By Dave Powell - Everybod Loves Celluloid on Fixing an Ailing Zeiss Ikon Contaflex Super B SLR – By Dave Powell

Comment posted: 17/12/2022

Brett Rogers on Fixing an Ailing Zeiss Ikon Contaflex Super B SLR – By Dave Powell

Comment posted: 03/01/2023

The installation may be less conventional than other types of camera, but the Synchro-Compur shutters fitted to these are not so very different to non-reflex versions. Granted, they have automatic aperture stop down. But that doesn't add a lot of extra complexity in itself, and most—not all—of the internal components are identical to those found in rangefinder or scale focus designs using the same size and class of shutter.

There were many iterations of Contaflex from the earliest Contaflex (retrospectively the Contaflex I) through to the last S variants. Not to mention those cheaper Pantar lens models equipped with Prontor reflex shutters (or the 126 Contaflex). Working on each type has its own variations. Timing the shutter/aperture/meter/ASA calibration on the original Super model is arguably one of the most tedious processes. By comparison, shutter work on the Super B, auto aperture notwithstanding, is generally less trying, because uncoupling/coupling the shutter to the camera body uses a more modular approach than the gear mesh EV arrangement the first Super was fitted with.

The Super B is a reasonably reliable camera. I say "reasonably" because, whilst there are certainly still examples that may be found with 100% working, accurate, meters—it's not surprising that some selenium cells may no longer be fully functional. The problem all these SLRs have (Bessamatics, Retina Reflexes, Contaflexes) is everyone talks about how complicated they are; but nobody—almost, anyway—actually services them, fully. Thus, shutters stick, focus jams, etc and they're written off as "unreliable". I don't think they are that bad to work on *mostly*. When a Contaflex has actually received a similar level of attention more frequently bestowed on Eg a Leica, Rollei, Canon, Nikon et al from the same period—it will work very reliably for a long time. Unfortunately, that does take a bit more than twitching the shutter blades with a toothpick—but good on you Dave, for at least, taking a look. It's further than most owners will dare to venture. ;)

Best Regards,

Brett Rogers

Comment posted: 03/01/2023