The 35mmc site mostly concerns gear and experiences, and I admit to having collected way too many lenses myself. It would take a heart of stone to spend as much time with cameras and lenses as we do, and not develop some attachment to them. But there comes a time to think about photography in its own terms as a fine art, and I find it equally impossible to spend years with a camera and not also think about light and dark, background and foreground, orientation and disorientation, even symbolism and metaphor; and all the other qualities that are fair game for the arts.

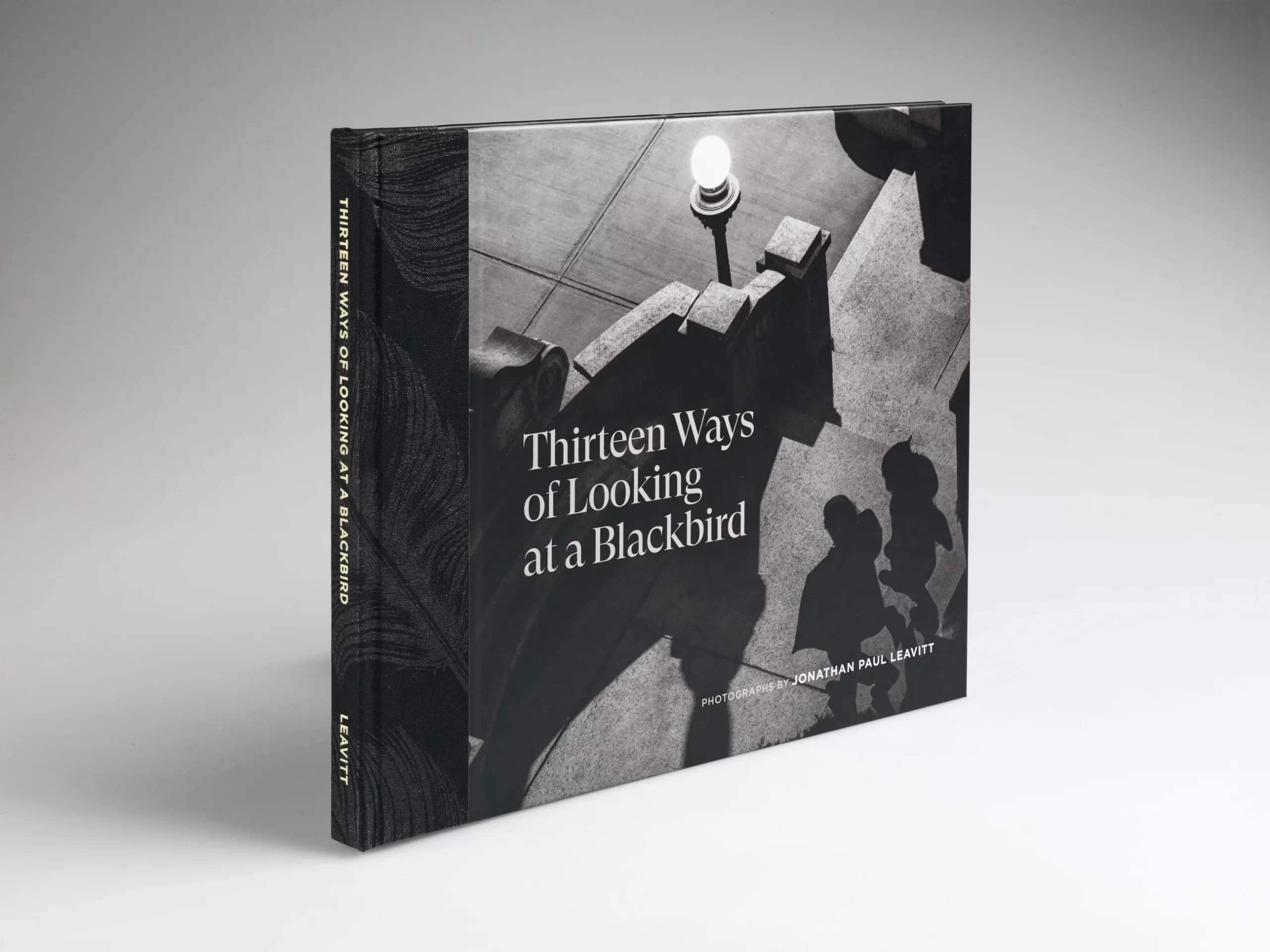

This post discusses these artistic issues using examples from my new book, Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird, a photo essay based on the poem by Wallace Stevens. The poem consists of thirteen epigrams, each interpreting the idea of a blackbird in a different and very original sense. The book contains no photographs of blackbirds, except for a cameo appearance in the credits, because it is not a literal representation of the poem. Rather it represents a series of further thoughts as extensions of Stevens’ imagery. For example, where one line spoke of “the shadow of a blackbird“ to symbolize doom and foreboding, I asked myself what other images might amplify those sentiments, while still recalling the idea of a blackbird.

So let’s discuss two stanzas and see how this goes. First comes the opening:

Among twenty snowy mountains

The only moving thing

Was the eye of the blackbird.

Stevens depicts the blackbird as an all-seeing presence, perhaps even a deity. It seems to supervise vast territories, presumably from a high perch in the mountains. The poem does not actually say the blackbird occupies a high perch. For all we know it could be burrowed in a cave, but it seems to represent something supernatural or mystical in nature. So what can we contribute towards this idea using photographs?

It starts with the line “Among twenty snowy mountains”. What is a snowy mountain? A photograph from an airplane flying over the Alps at sunset would be a straightforward illustration, like a children’s book. We have all seen beautiful aerial photography, and these days it is better than ever, but our goal is to focus on something beyond that. To what else can “twenty snowy mountains“ refer? I spent some time looking at rooms full of elderly people with white hair, and produced at least two candidate images involving their “snowy mountains“. Ultimately, I settled on this photograph of white plaster busts stored in a museum. One reason is that they bridge to the next line of the poem, and from there to the concluding line.

The next line is “The only moving thing”. Plaster busts are not real people; they are not moving things. The same is true of the white marble statues forming the façade of the cathedral, but on a larger scale. I chose an image taken at night, the time of greatest stillness, in which the white heads of statues form a snowy mountain of religious imagery. I chose a lens with spherical aberration, which renders greater sharpness in the center and visible fall off towards the corners, emphasizing the optical quality of eyesight that interposes itself between reality and the viewer, perhaps suggesting that the scene is perceived through the eye of the blackbird.

By using pictures of a cathedral with Jesus or the Virgin Mary at the center, we have now alluded to religion and God, taking us further in the direction of Wallace Stevens’s hint that the blackbird is a nature deity. We have populated the page with snowy white objects that do not move, and which represent the holiness and sacred things surrounding God.

Now comes one of the hardest photos. The next line is “the eye of the blackbird“ and for our purposes it basically refers to the eye of God, or some all-seeing nature deity. What further images spring to mind? Fortunately, the answer came in a dream, of a person running in his sleep, viewed from above in bed, with the lines he impressed in the sheets radiating outward like rays of light. I rented a studio and hired a model, and was pleased to discover that the model, who has a white hair, resembles a prophet or holy man himself. And so there he is, the eye of the blackbird, with a head like a snowy mountain.

Now let’s jump to the fourth stanza:

A man and a woman.

Are one.

A man and a woman and a blackbird

Are one.

We all know what Stevens alludes to when a man and a woman become one. But that union does not remain pure. Other characters come into play, and they are blackbirds, foreign to the relationship, and dark things too. They are not bluebirds.

There is plenty of sexy photography out there, some more prurient than others, illustrating the beauty of a man and a woman in various stages of becoming one. I resolved not to go in that direction. It’s been done before, to say the least, but more important it would be a literal representation of the text, rather than a further thought beyond the text.

So we begin with a grab shot of a man and a woman making their way through an art exhibit. While holding onto each other, they are looking and pulling in different directions, and behind them appears a painting of a woman with multiple faces and multiple eyes. The man and the women are together as a couple, but they have not yet become one. They are distracted by the world, and the paintings that distract them are also paintings that deal with the subject of distraction or fragmentation.

The next photograph (Plate 10) corresponds to the line “are one“. It depicts that memorable turning point on a date when the man ventures to touch the woman deliberately, and she accepts it. This is actually the moment they become one, not later in the evening when they take their clothes off. This this was a difficult shot, literally under the table in a jazz club by the light of a single candle at F1.0.

In Plate 11, corresponding to “a man and a woman and a blackbird”, we see a couple in silhouette, their images black like a blackbird, and next to them stands the upside down shadow cast by a streetlight. It seems counterintuitive that an illuminated sphere would cast a shadow, and this sets a surreal tone and a sense of spatial disorientation. Also the streetlight looks vaguely like a human head, so there are now three silhouettes, one of which is upside down and foreboding, ironically the shadow cast by a light. A blackbird has arrived in the relationship, but the man and the woman are still together. The blackbird is not yet one with the couple.

In the final photograph, corresponding to the line “are one“, a giant shadow, larger than both people , larger than the frame of the photograph, divides the frame into two areas. The couple are now moving in opposite directions, both engaged in the same occupation of beachcombing, but divided by the shadow. It is a moment of divorce. Now the blackbird, in the form of the great shadow, dominates the relationship. Anyone who has been in an unhappy relationship will recognize this moment.

One of the hardest subjects to talk about is taste, but one cannot understand art on its own terms without some reference to it. In this series, you have seen a couple on the beach at dawn, another couple holding hands, and an architectural photograph of a cathedral, which are potentially banal or trite subjects. It is critical to the nature of this project that we extend the readers appreciation for what kinds of images are relevant to the poem, without resorting to cliché. This was certainly Wallace Stevens’ view of poetry. He viewed metaphor as a means to escape the cliché of daily life.

What distinguishes Plate 12, a couple on the beach at dawn, from just another stock beach image? Although taken at dawn, the sun is not visible, nor even the sky. The only clue that it’s dawn, or possibly sunset, is the length of the shadow in the foreground. Also, the horizon is not visible. If it were visible, it would exert a powerful influence that converted the image into a landscape photograph. Instead, the sand and water form a backdrop or aquarium against which two figures stand out. The fact that they are both walking in the same posture when they cannot see each other, perhaps suggests they are executing a subconscious dance, still entangled without being aware of it. They are still a couple, even when moving in opposite directions.

A couple holding hands in Plate 10 is another potentially trite scene. What helps ward off the sense of cliché is partly a degree of spatial ambiguity that results from excluding any entourage such as furniture or the even table top. But what also helps is the slight edge of danger in witnessing such an intimate moment. Though not pornographic in the slightest, it is truly the moment when this couple became one.

In an argument with Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens is reported to have said, “the trouble with you, Robert, is that you write about things“. This little album of photographs is not intended to be about subject matter; not intended to be about things. Its goal is to transcend literal subject matter, to move past familiar images and to search through our perceptions for those rare moments when the world arranges itself into a poem.

The book is available here from Brilliant Editions. There is also an interview here.

by Jonathan Leavitt

Share this post:

Comments

Geoff Chaplin on Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird

Comment posted: 10/02/2024

Thanks for an inspiring post! We can only hope we have the imagination to do something similar.

Gary Smith on Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird

Comment posted: 10/02/2024