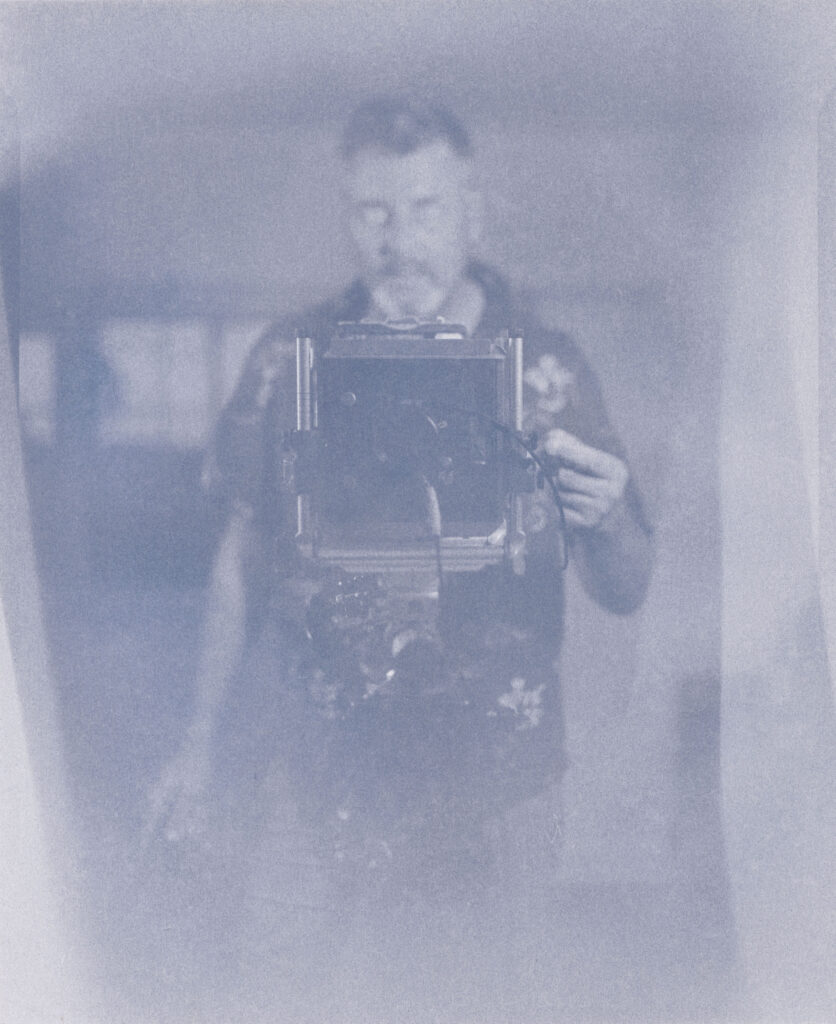

For the past few years, I’ve been exploring large-format paper negatives which has been a transformative journey that has reshaped both my creativity and my sense of wellbeing. This traditional method, steeped in the history of early photography, connects me to a slower, more deliberate process that encourages mindfulness and experimentation.

Paper negatives are taken on photo sensitive paper instead of film. Photo paper is much less sensitive to light than film so images require longer exposures or strong flash. Each exposure is hand developed in the darkroom, producing a negative on the paper.

Here’s what I’ve discovered along the way.

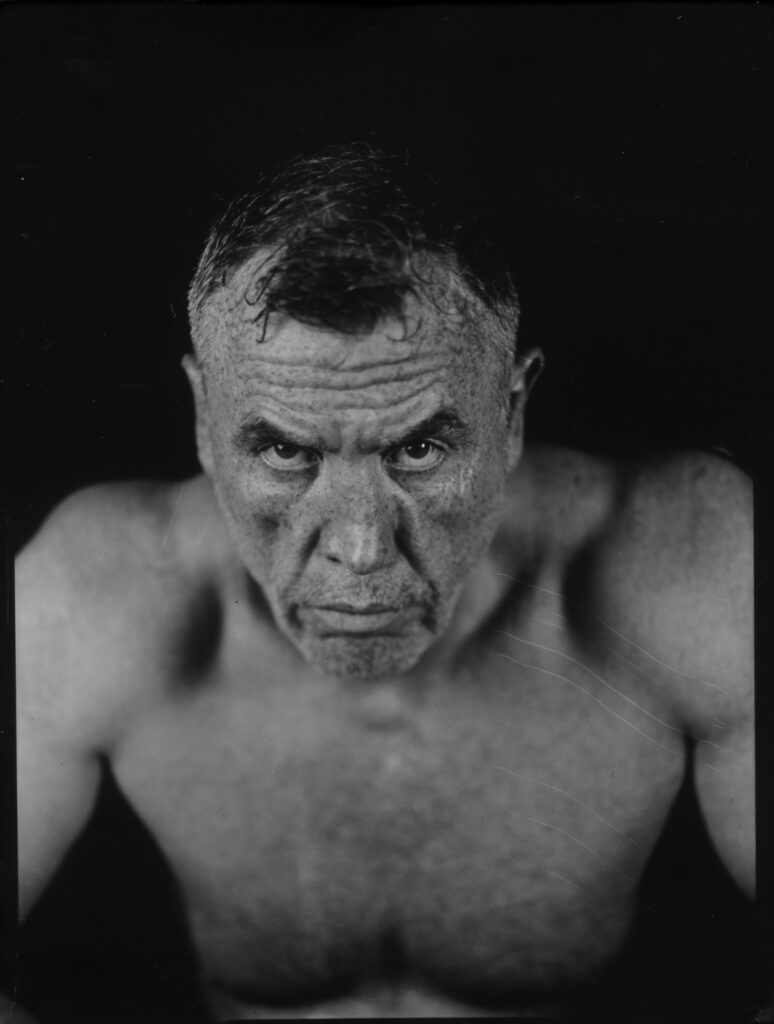

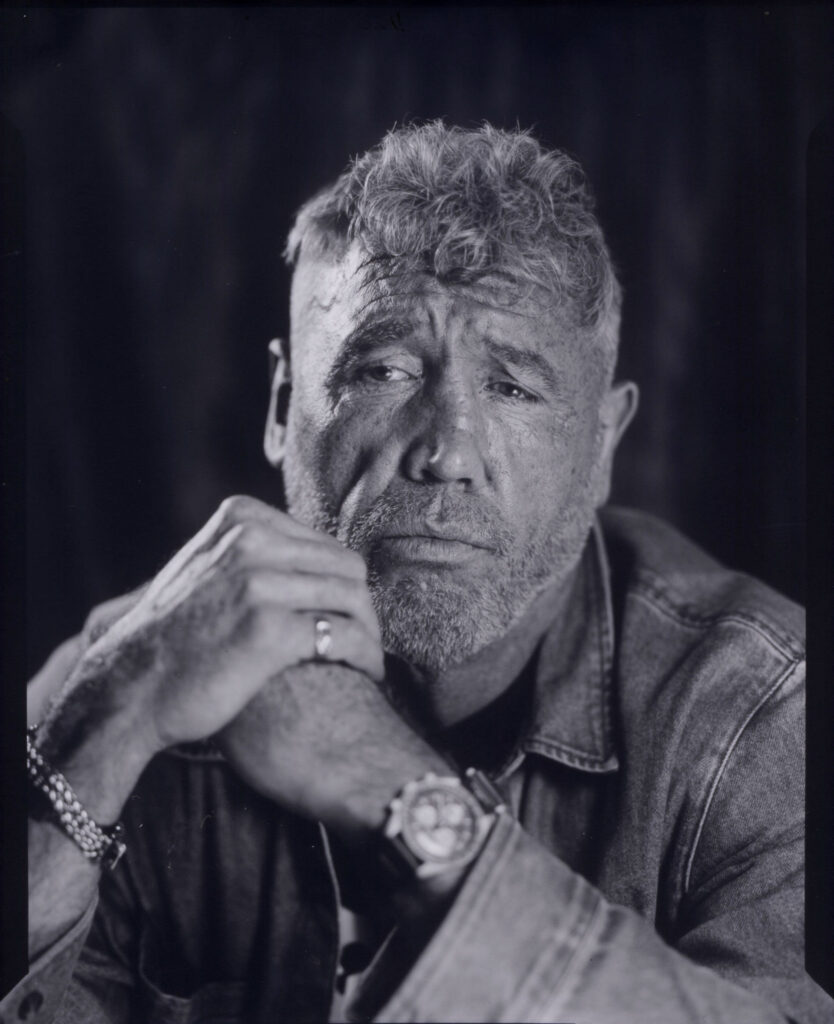

Embracing Imperfections

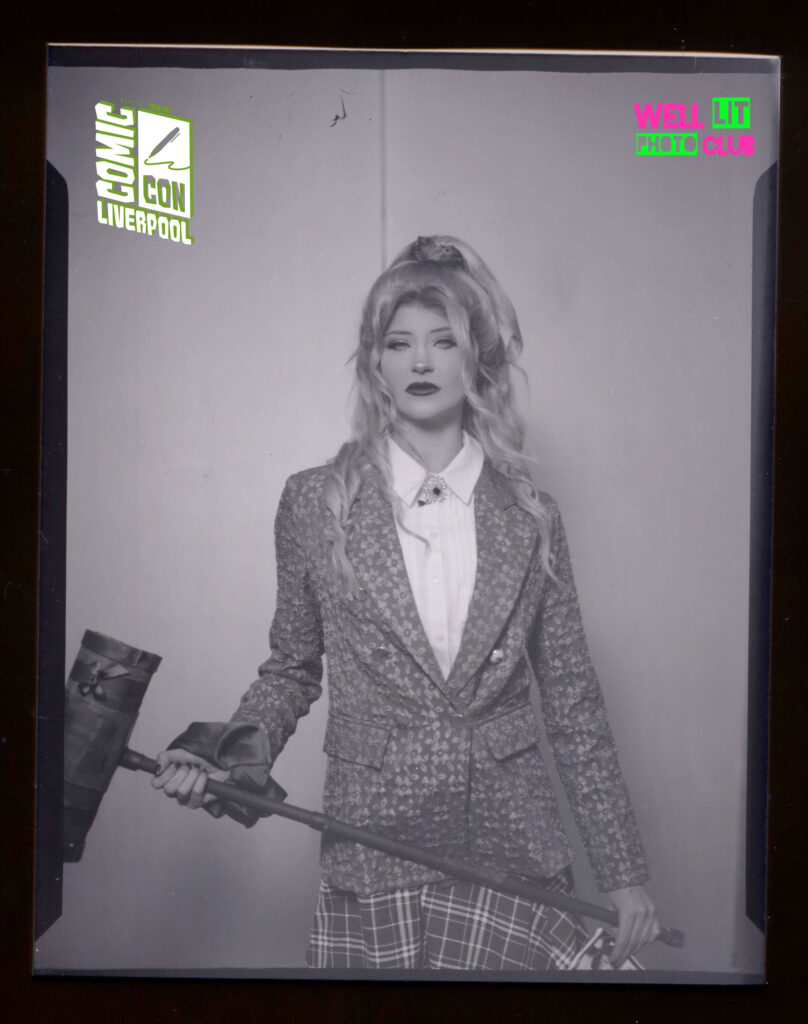

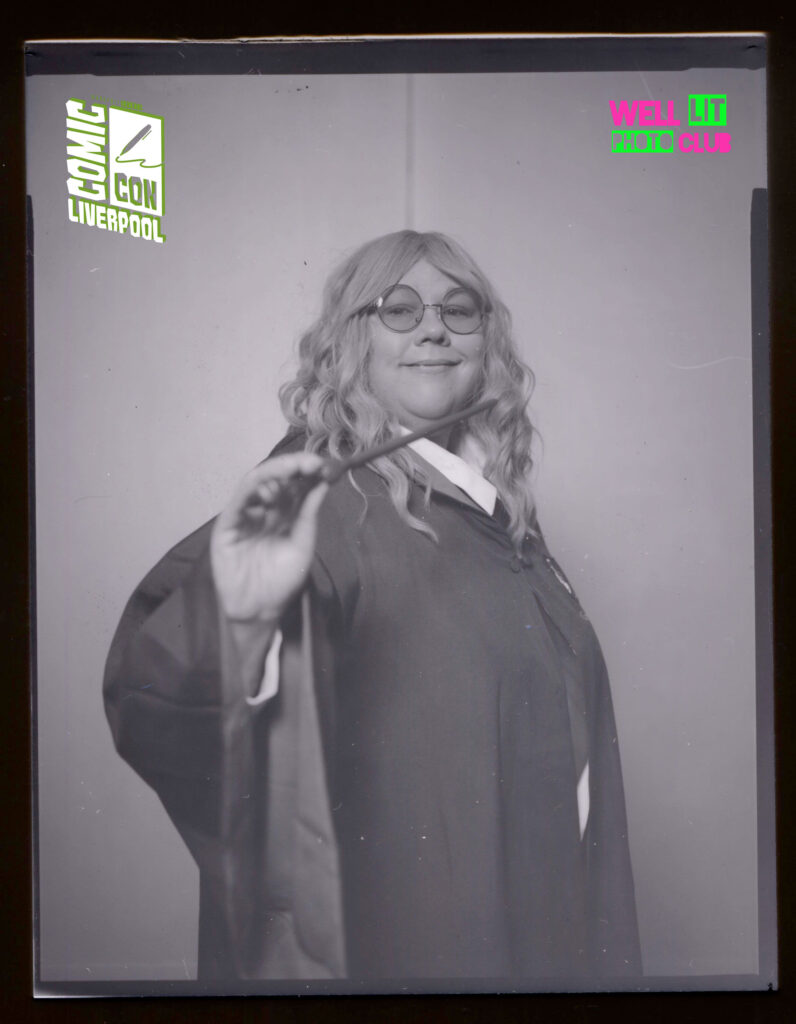

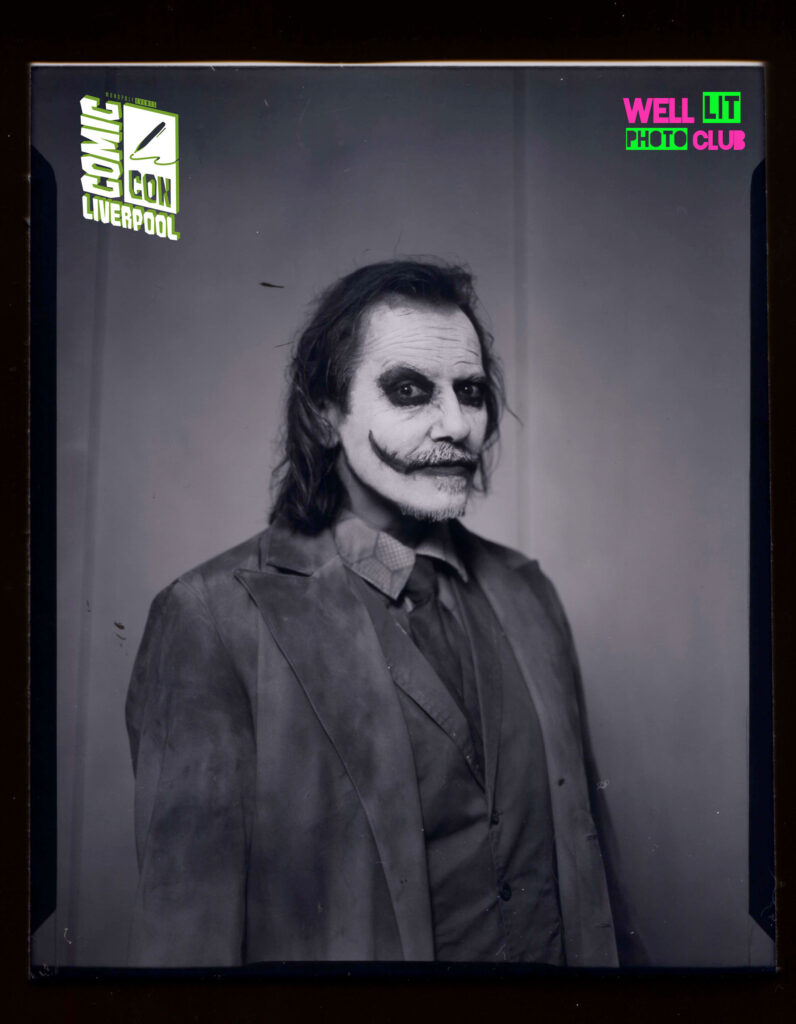

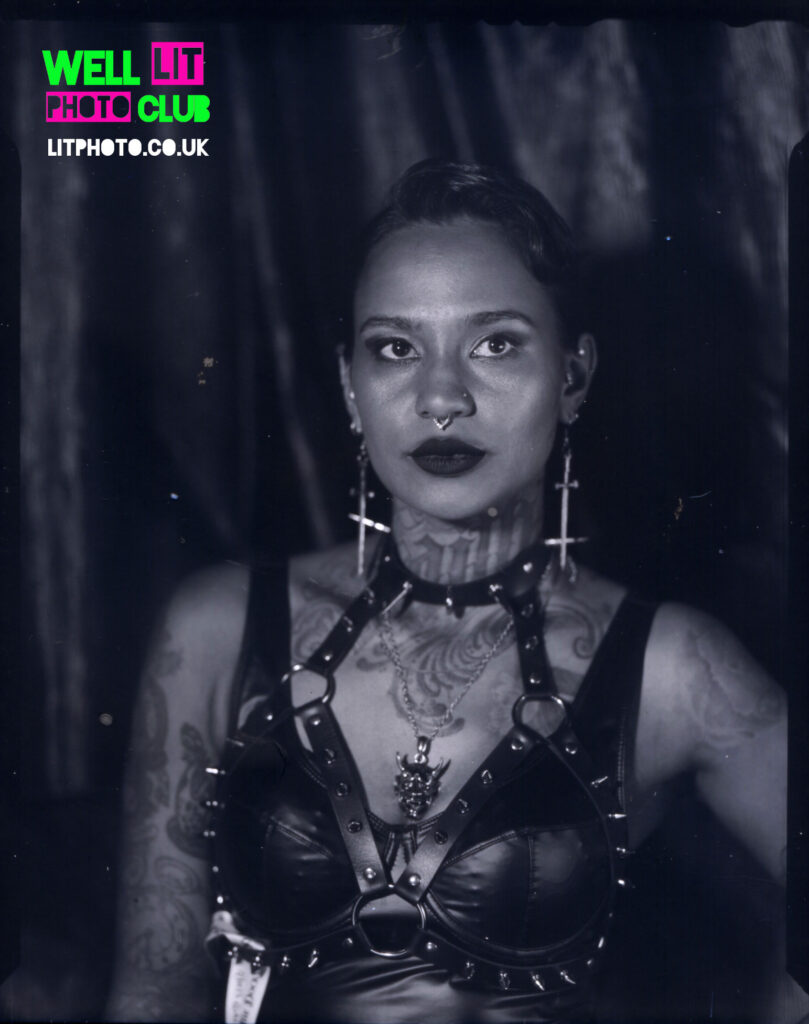

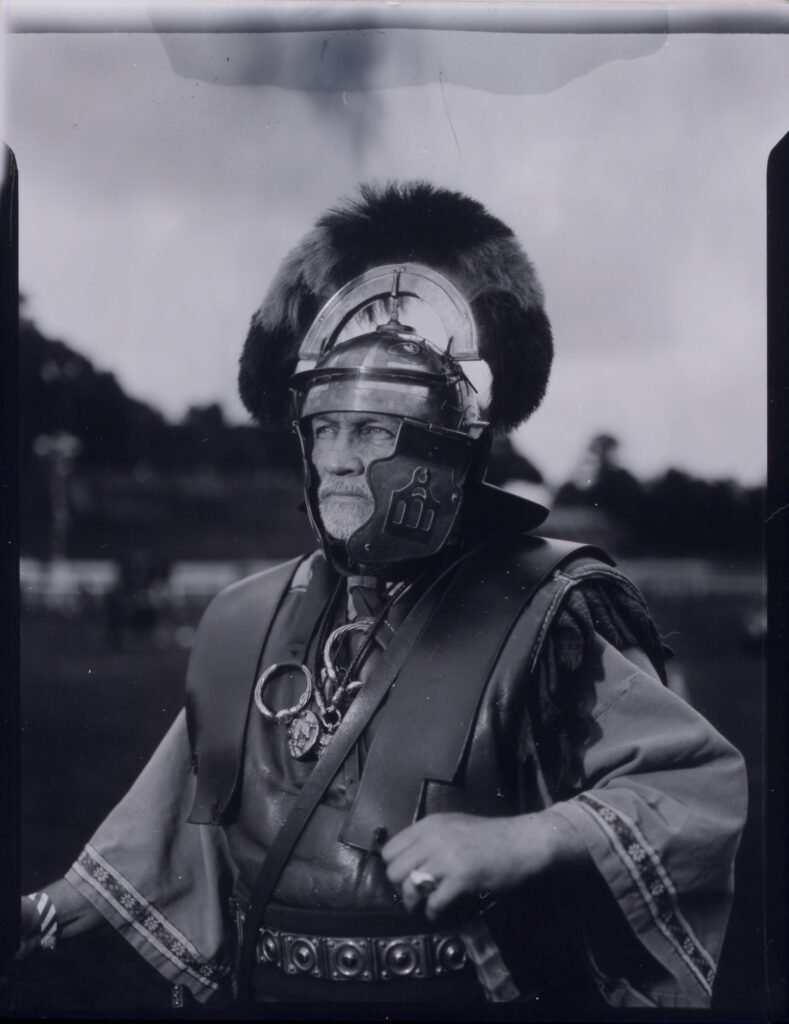

The pursuit of a flawless paper negative can feel at odds with the organic, tactile nature of this medium. Some of my favourite images are far from technically pristine; they’re riddled with scuffs, fingerprints, or feature blown-out edges from half-exposed sheets. These visual quirks bring a raw, unpredictable character to the images that are always beyond my control.

Historically, photographic paper was one of the earliest tools used to capture light. Long before film became the dominant medium, photographers used salted paper and albumen prints to document life. William Henry Fox Talbot invented the paper negative process in 1840, which he called the calotype, or sometimes the talbotype. Talbot’s process involved treating high-quality writing paper with a solution of silver nitrate and potassium iodide. The paper was then dried and could be stored indefinitely in the dark. Before exposing the paper in a camera, Talbot would sensitise it with a solution of silver nitrate, acetic acid, and gallic acid. After exposure, Talbot would develop the image with a similar solution and fix it with potassium bromide or sodium thiosulphate. The final negative was usually waxed to make it translucent.

Today, there are countless varieties of photographic paper, each with its own texture, contrast, and tone. Also factoring in that most of the photo paper available is vintage then these unique qualities turn every shoot into an experiment. I find it liberating as photography becomes more about the medium and the magic of the paper and less about me.

Shooting on paper also negates the pressure of technical perfection. Unlike film, where exposure must be spot-on, paper negatives are developed by eye under the red glow of the darkroom, you stop the process when the image feels right, creating a fluid, intuitive experience.

Shooting on paper is also one of the most cost-effective ways to practice traditional photography. Photo paper is affordable, easy to source, and my first paper negatives were developed using nothing more than plastic takeaway trays and taken on a homemade pinhole camera.

The ISO Sweet Spot

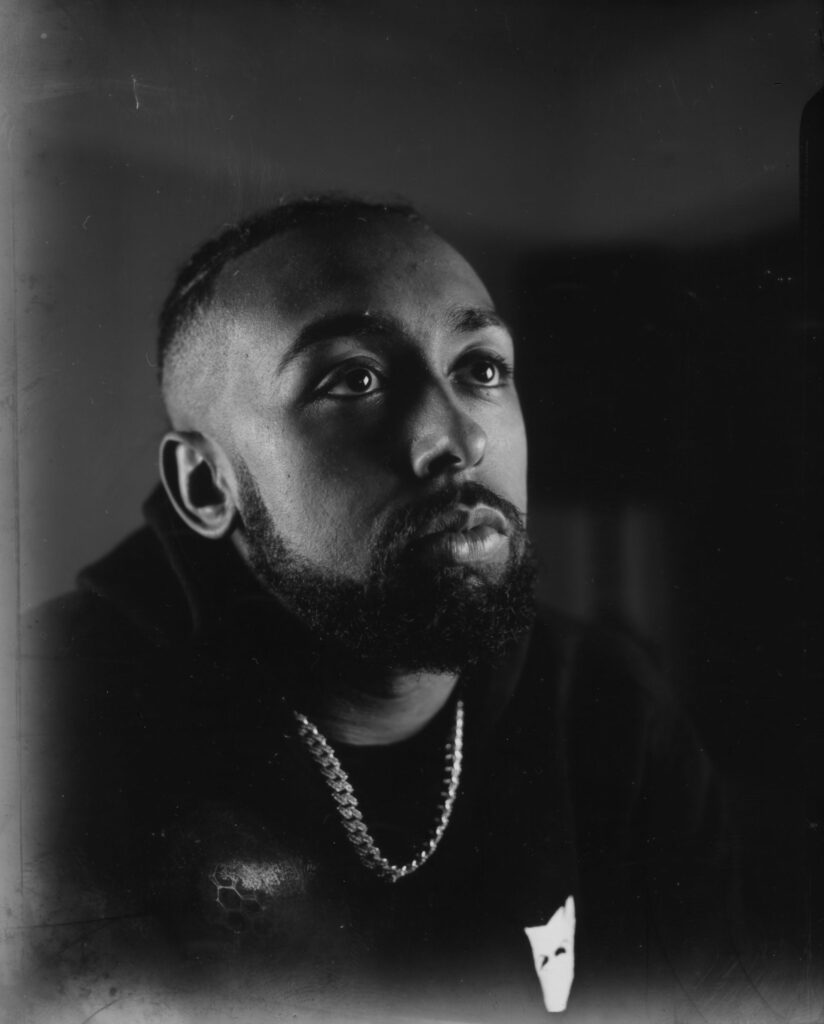

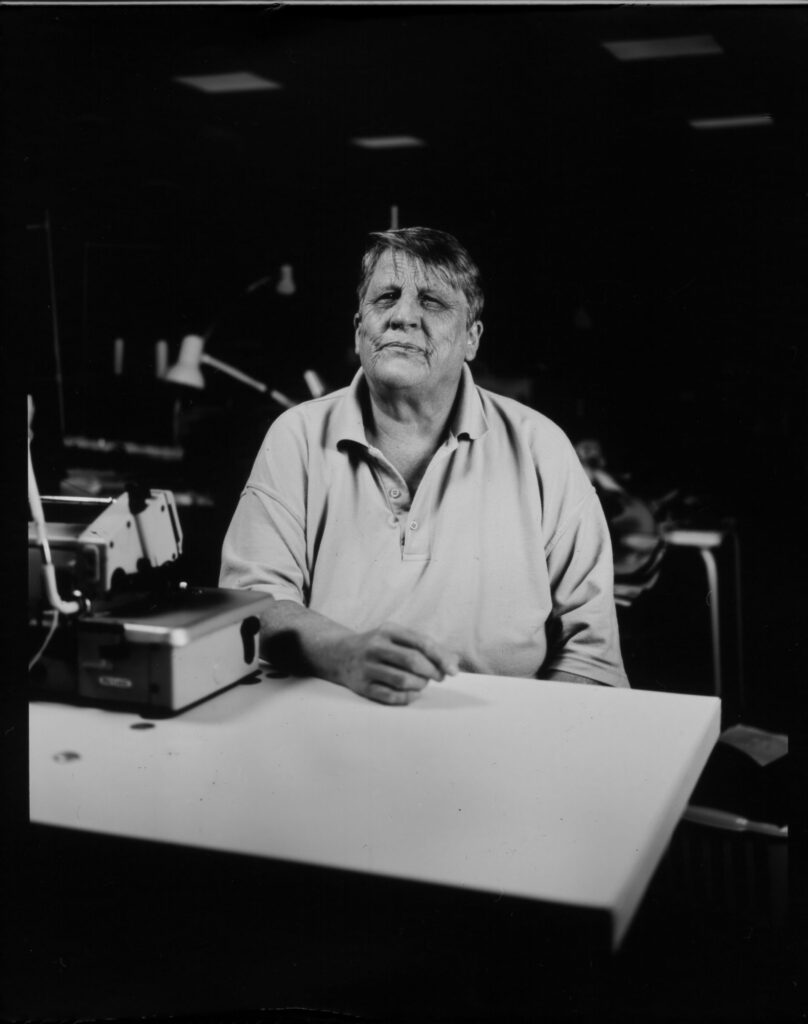

One of the most fascinating aspects of paper negatives is their tonal depth and texture, especially in portraiture. With an average ISO of around 4, photographic paper renders skin tones with a rich, treacle-like quality, reminiscent of 19th-century tintypes and wet plate photography.

More than Black and White

It wasn’t until my third or fourth shoot that I discovered the magic of scanning these paper negatives in colour instead of just black and white. The results revealed subtle hues unique to each paper; from deep warm sepia tones to cool silvers and blues. When combined with the natural textures of some of the fibre-based papers, these hues and inherent grain can give some images a painterly quality.

The Drama of Development

There’s an undeniable thrill in watching a negative come to life in the darkroom. The image appears gradually, ghost-like, in the developing tray; a process that feels as much alchemy as art. Deciding when to stop development is a creative act in itself, imbuing each image with a sense of spontaneity and individuality. This tactile, immersive process offers a dopamine hit unlike any other. Each image I develop provides a fresh opportunity for discovery, and I often find myself losing hours in the darkroom, absorbed by this act of creation. It’s meditative and rewarding.

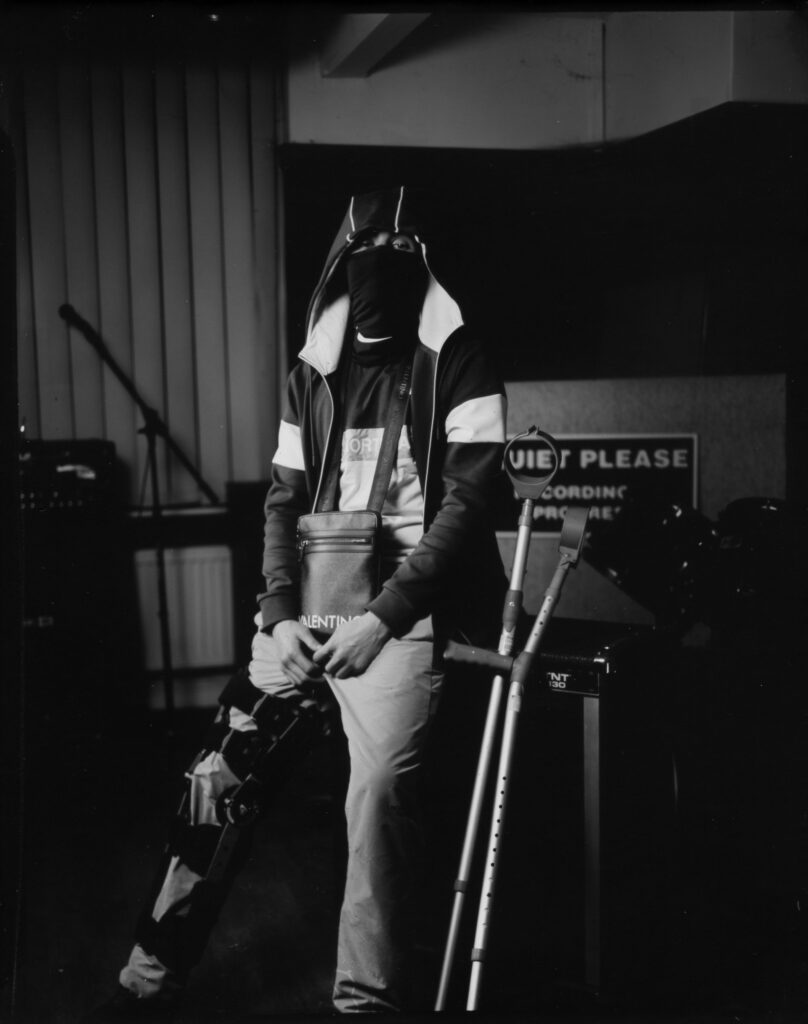

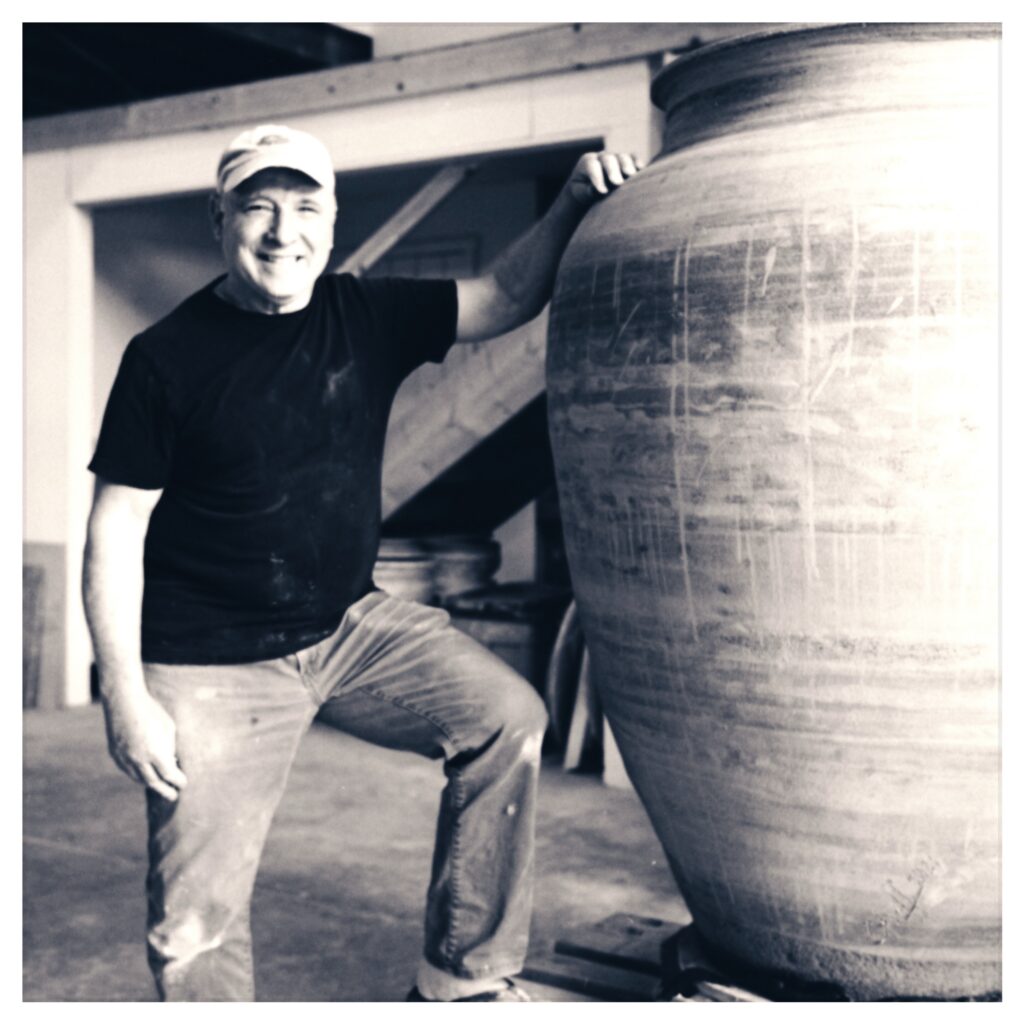

Large-format paper negatives demand a slower pace, which has been a welcome shift for me. The heavy equipment, precise framing, and longer exposures naturally encourage patience. Every step; from focusing to composing the shot requires intentionality, slowing me down in a way that feels restorative.

This slower pace extends to my interactions with subjects as well, which leads to more meaningful interactions with people. Strangers are often intrigued by the vintage camera and the hands-on process. This has inspired me to run heritage projects sharing portraiture and pinhole photography with support from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, as well as running pop up portraiture at events such as Comic Con Liverpool, Tattoo Festival Liverpool, Chester Heritage Festival at Chester Races. I feel like it’s my responsibility to capture people on paper and to share this traditional process.

Ian Gamester is a film maker, photographer, college lecturer and social entrepreneur. As a film maker Ian has shot over 100 music videos for artists all over the globe, as a college lecturer and social entrepreneur Ian has delivered training and ran creative projects all over the UK supported by agencies such as Comic Relief, National Lottery, Arts Council, etc.

Share this post:

Comments

Gary Smith on What I Love About Paper Negatives

Comment posted: 11/02/2025

Comment posted: 11/02/2025

Geoff Chaplin on What I Love About Paper Negatives

Comment posted: 12/02/2025

Comment posted: 12/02/2025

Jeffery Luhn on What I Love About Paper Negatives

Comment posted: 13/02/2025

Absolutely love what you're doing! Your results are stellar! The shallow depth of field indicates that you're interaction with subjects is a challenge that you've conquered. I imagine scanning these images is instrumental is preserving sharpness and rich tonal range. Great.

When I was a photo student in the 1970s we had assignments to shoot 8x10 paper and make contact prints. The 'face-to-face' contact prints were not nearly as sharp as yours. I often wondered why my various instructors assigned oddball projects including use of glass plates, micro film, and the most outrageously time consuming of all: color dye transfer printing! What a nightmare.

Now that I see your results from scanning, I can see the value in reviving that process. The detail has the potential to be even sharper that shooting negative film because it's down to just one step. Great article! I'd like to read about your equipment, daylight exposures, lenses, etc.

Jeffery

Comment posted: 13/02/2025