A recent auction job lot turned up a working Richomatic 35, a camera I vaguely remember for its very modern design for its day but not one I had taken much interest in. A great deal of thought must have been invested in its design I discovered, including features not usually found on such a basic camera at that time.

It dates from the early 1960s when simplification of camera operation was being sought by many manufacturers, led, of course by Kodak. Their entry level 126 and later 110 cameras dumbed things down to a very basic level indeed with drop-in film cartridges, fixed shutter speed and focus, and plug-in bulb flash devices and, later, built-in electronic units. Other manufacturers followed suit, their ranges including the option of more advanced versions but still aiming for simpler operation. These usually offered a good lens with rangefinder focus and a coupled meter to appeal to a more experienced photographer.

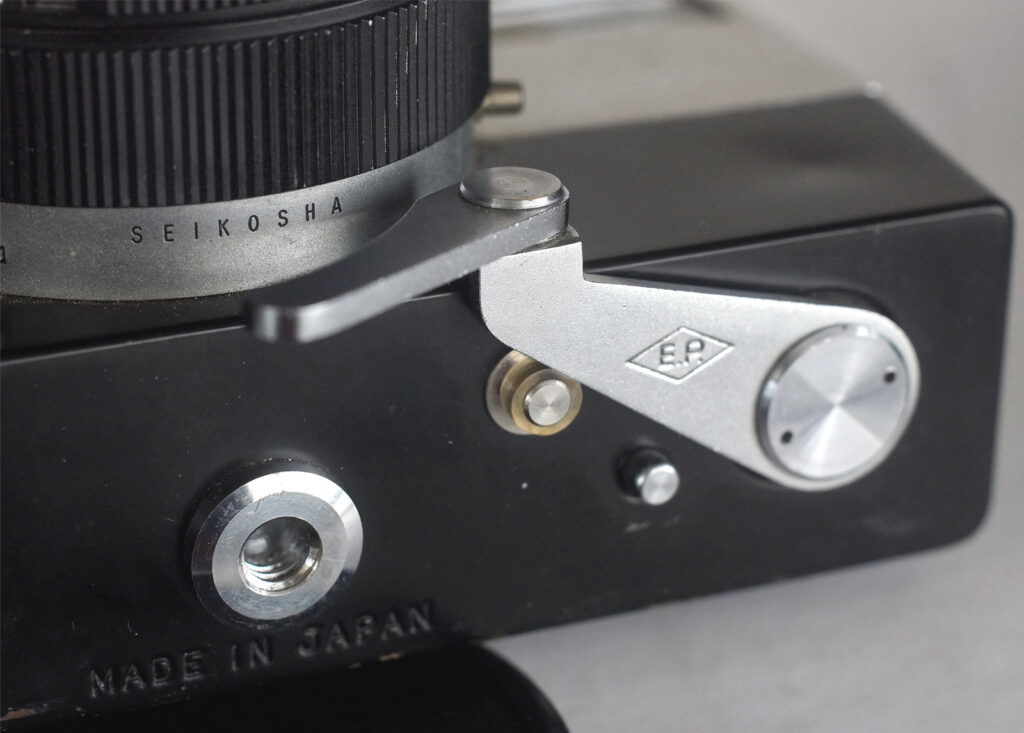

I was so impressed with the Richomatic 35, when another example came up a little later on which looked in much better shape cosmetically at a reasonable price so I bought it also. This one was not stamped on the rewind lever with the US forces ‘EP’ mark (EP for Exchange Post) like the first and looked to have led a less active life, accounting for its less worn look. But all that glistens….

The cameras

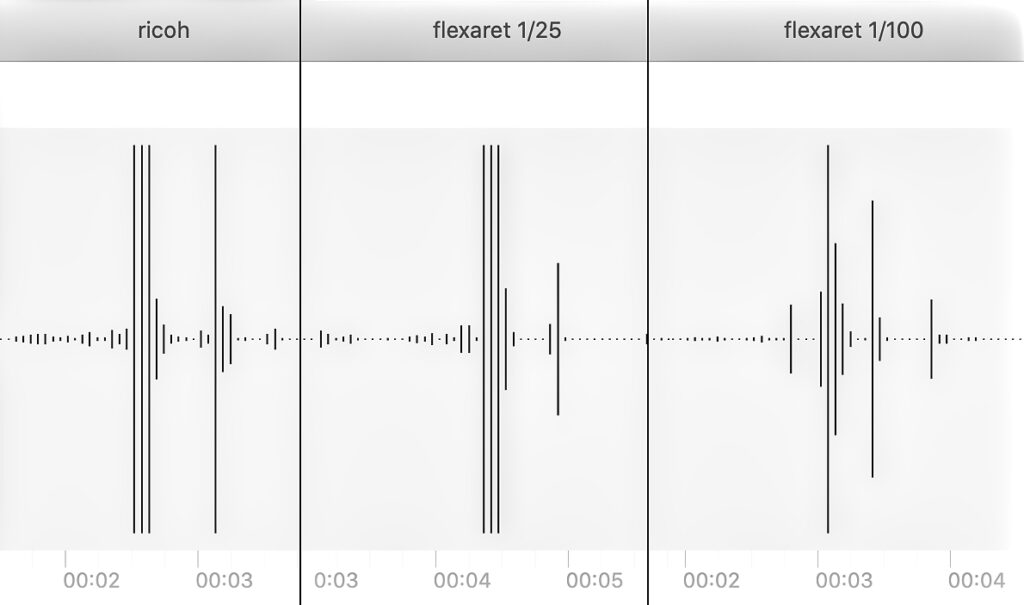

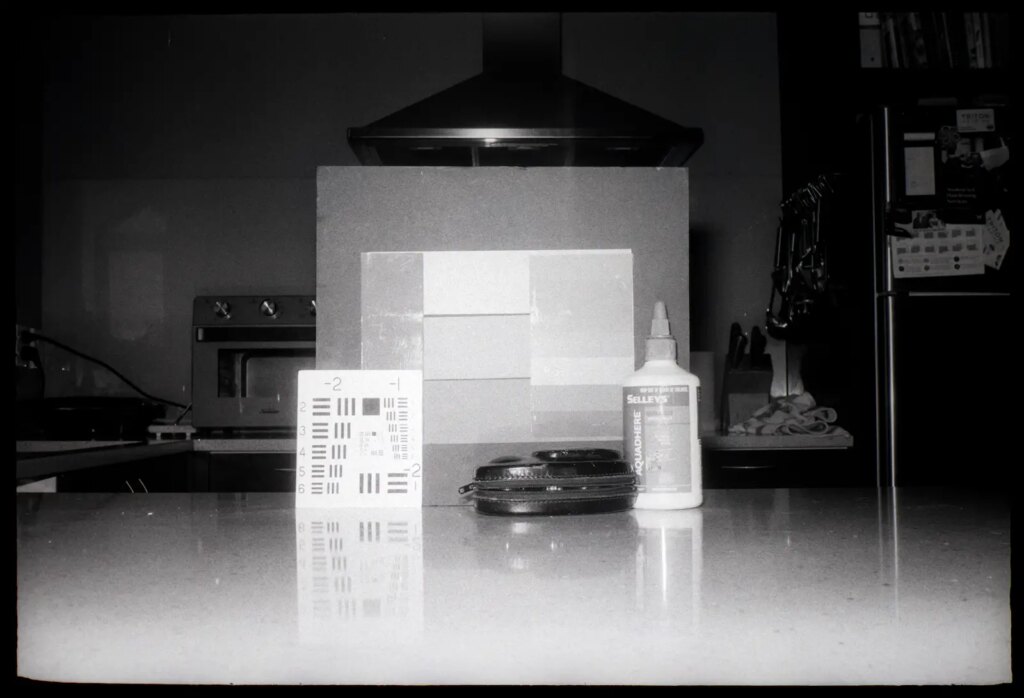

The Richomatic 35 is designed to take standard loading 35mm cassettes, with a good rangefinder focussing, f2.8 lens and a coupled selenium exposure meter which automatically traps the aperture against a fixed shutter speed as the release is pressed. Shutter priority automatic in effect but at only a single speed plus delayed action which still works if a little hesitantly with the both examples. The speed is generally taken to be around 1/125sec and appears to be the case for the first example. My first film in the second camera was heavily overexposed so I assumed it was running slow. Checking it against my other cameras it is not much more than 1/25sec judging by their respective sound traces using the voice memo app on my Macbook. Photographing my speed tester later showed it to be 1/26sec.

The shutter is marked Seikosha, a quality Japanese maker. An advert from Dec. 26, 1962 suggests it has a range of speeds but that is the only reference I have found that mentions anything other than the single speed of these examples. Even McKeowns seems confused, saying it has shutter speeds ‘up to 200’. In fact it is the film speed scale that goes up to 200, ASA that is. The descriptions in the advert could be swapped over apart from reference to the rangefinder which the Auto 35 never possessed.

The Richomatic 35 lens is a 4 element f2.8, marked Ricoh Kominar, so not apparently made by Ricoh. Kominar produced lenses for other manufacturers. The lens is surrounded by an annular selenium meter cell with a ring to set the film speed rating in ASA and DIN between 10 and 200 ASA and DIN equivalents. It has a 52mm filter thread, the filter covering the meter cell and therefore compensating for it automatically.

The finder is placed at the left hand end seen from the back so your nose doesn’t get in the way if you are a right eye type and brings the eyepiece closer to the eye. This is a big help wearing glasses, greatly reducing the eye point, but is less convenient if your left eye is dominant, but still not an arrangement normally seen. The Leica M models come to mind and Fujifilm X mirrorless, rangefinder style digitals nowadays for example.

The Richomatic 35 is very well made cameras of all metal construction and high quality castings and assembly. Heavy in the hand but quite small with all the controls well placed if a little unconventional.

Wind on is by a fold-out, base-mounted lever similar to the one used by Canon in some of its earlier models, allowing quite rapid film transport with the left hand and reversing the usual left to right film transport direction. The large shutter release lever is concentric with the lens rather than mounted in the top plate and falls readily under the fingers of the right hand. Focus is conventionally operated. Unless flash is being used, that is all that is needed from the photographer. The old pressman’s three Fs – focus, frame, fire – after f8 and be there of course.

There is a hot shoe for a dedicated bulb flash, quite an advanced feature for the time not becoming common until the ’70s, as well as a standard co-ax flash cable socket. The manual says electronic can be used which I assume is not using the hot shoe because of the different timings between bulb and electronic. Bulb flash needs 18-20 milliseconds or 1/50sec or so to reach maximum output and would fire before the shutter opens at any faster speed. Possibly it was expected that the co-ax would normally be used to connect electronic units and an internal variation is provided to allow for the different timings required. Not having a bulb flash I am unable to test this theory but an M/X lever is more commonly used. There is a small circular window marked ‘Flash’ on the lens mount which changes colour according to distance as the lens is focussed. Also, there is a needle in the finder that moves across the base of the bright frame indicating, when it enters a red section, that flash is needed. In that event the coloured indicator on the lens comes into play.

On the Richomatic 35 back is a circular calculator for flash settings and a lever on the lens that is marked A for automatic available light photography and with three flash settings, 1, 2 or 3. The guide number of the unit in use is first set on the dial and the colour shown on the lens mount indicates a number on the rear calculator. This number is then transferred to the lever on the lens mount, setting the correct aperture for the distance and flash guide number. Quicker to do than describe.

Rewind is by a fold-out crank which is much easier to use than the more usual rewind knobs of this period. A small pin is depressed when the lever is folded out that engages a clutch. When the lever isn’t pressed onto this pin and folded away the drive disconnects allowing the film to be wound on. The more usual rewind knob will turn in reverse indicating film is wound on, which doesn’t require such complexity and usefully indicates film is winding ok.

To disengage the take-up spool there is the usual, seperate button which has to be held in whilst rewinding.

Finally, the cases are of exceptional quality and still in very good condition considering they must be around 60 years old. The strap, which attaches to the camera, has a novel means of attachment, a kind of bayonet arrangement which is very secure but simple to attach/detach. Its only problem is that it rotates freely and the strap eventually can become very twisted.

Ricoh designers were ahead of the game in some areas and definitely marched to their own drum.

Shooting the Richomatic 35

On the first one the eye-piece is a little grubby and the rangefinder patch tricky to get aligned, needing careful eye positioning but fairly average for the time and accurate. Focus and film speed setting rings are quite stiff but still useable. The second one is smoother and has clearly had less use but the meter is completely unresponsive. It can still be used manually by using the flash settings for apertures. My tests suggest that these are ‘A’= f2.8 when the needle is fixed in the red, ‘1’ f4.5, ‘2’ F11 and ‘3’ F22. The two stop spacing distributes the flash exposures for best effect utilising film’s exposure latitude, part of the colour-coded simplification approach. By using filters I can vary these exposures further.

The Richomatic 35 shutter release is similar to but a little firmer than the models of the Agfa Silettes and Optimas and can help with a smooth release. The Agfa version fitted to my Super Silette Automatic is feather light by comparison, not needing to move the aperture limiter.

The unusual wind-on allows a fairly fast firing rate if needed.

For normal shooting the lever on the lens mount is left on ‘A’ giving automatic available light exposures, the meter controlling how far the aperture is stopped down as the shutter release is pressed.

So, basically, a point and shoot with shutter priority automation plus accurate focus by rangefinder.

Richomatic 35 Results

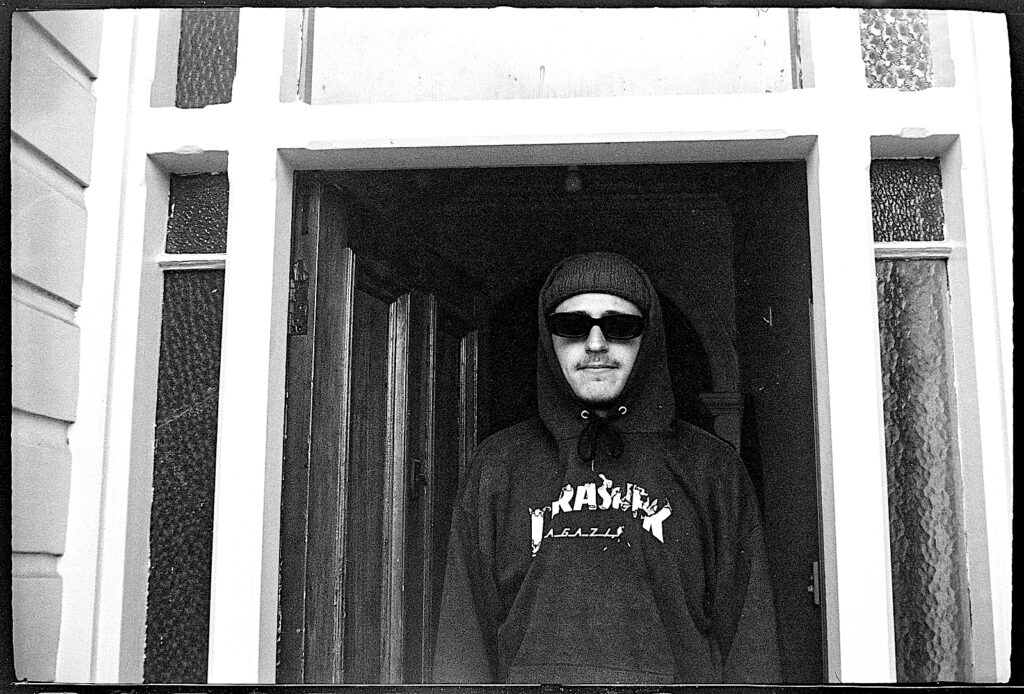

By coincidence, my grandson Harry wanted to try a film camera. He has used a digital mirrorless for some time and a disposable film camera recently and quite keen, so I gave him this to use. It seemed a good way to test the ease of use claims of a camera that is intended for someone with a little experience rather than a raw beginner. The second one I used myself.

He had been sold a roll of Ilford XP2+ which produced a couple of problems. First, the film speeds on the camera only go up to ASA/ISO 200 – XP2 is 400 – and second, it is intended for C41 colour processing. Thinking positively, this gave me the opportunity to try stand processing the film in 1:100 Rodinal, something I had read favourable reports about online. According to the Massive Development Chart web site, a further advantage is that this method of processing gives an effective film speed of ISO 200, matching the highest speed able to be set on the camera. Other than having a purplish colour and more than usual base fog the negatives turned out well, suggesting that the meter and shutter are still working fairly accurately. Selenium meters can be very durable if they are not exposed to light for long periods so this one must have been kept in its case all its life. I was unlucky with the second one.

I decided on FP4+ for the second camera, a film I am very familiar with, also processed in Rodinal but at 1:50 and conventional agitation. As mentioned, the shutter speed is running slow so my first film was overexposed but the second one was much better.

These examples come from both cameras as noted. The results are good considering the varied lighting conditions Harry tackled just using the camera’s meter. I had to juggle filters and flash settings to match my Sekonic meter’s readings.

Richomatic 35 Conclusion

I am taken with the little Richomatic which, despite its apparent simplicity, is very capable. It is very similar to some Adox Golf models introduced a few years later and the near identical Zorki 10 from the Russian manufacturer Kraznagorsk/KMZ. Perhaps they were all influenced in some way by the minimalist Werra from Carl Zeiss Jena which came on the scene in the mid 50s.

Despite lacking variable speeds (or even a working meter), it can deal with most subjects and a flash unit extends its range. Only having to focus and frame in natural light makes taking a photo very spontaneous, the object of the exercise after all for this type of camera. Flash is a little more complicated but a novel and not too difficult solution.

Harry says he enjoys his camera and once he had the hang of the unusual shutter release and wind, and the rangefinder all went well. So he is going to keep using it. I can echo that having tried the second example, they are a pleasure to use.

They were certainly quality products in all respects, fairly complex but innovative in many areas and simple in others, a quirky but capable product of the period. These two also highlight the ups and downs of using old cameras and makes the point that older, mechanical cameras are meant to be used and will suffer from inactivity. The more heavily used example here is still firing on all cylinders compared to the better looking one that has had less regular use. Either way, it is quite a testament to the skill of the people who designed and made them that they still function as well as they do.

Share this post:

Comments

Paul Quellin on Richomatic 35 – Two Contrasting Examples of a 1960s Quality Point & Shoot Camera.

Comment posted: 11/03/2024

Comment posted: 11/03/2024

Comment posted: 11/03/2024

Gary Smith on Richomatic 35 – Two Contrasting Examples of a 1960s Quality Point & Shoot Camera.

Comment posted: 11/03/2024

Comment posted: 11/03/2024

grain_frame on Richomatic 35 – Two Contrasting Examples of a 1960s Quality Point & Shoot Camera.

Comment posted: 11/03/2024

Comment posted: 11/03/2024

Joe Van Cleave on Richomatic 35 – Two Contrasting Examples of a 1960s Quality Point & Shoot Camera.

Comment posted: 12/03/2024

Comment posted: 12/03/2024

Bob Janes on Richomatic 35 – Two Contrasting Examples of a 1960s Quality Point & Shoot Camera.

Comment posted: 12/03/2024

Comment posted: 12/03/2024

Comment posted: 12/03/2024

Comment posted: 12/03/2024