It is certainly no exaggeration to say that film photography is coming back with a vengeance. Even the most die-hard celluloid sniffers had shelved or sold their analogue gear by the early 2000s; the stuff was, until recently, virtually being given away on eBay, at flea markets, or ended up in landfill. Film was dead.

Come 2019, and you suddenly see young urban people brandishing their Holgas or Prakticas (or sometimes proper cameras) left, right and centre; web platforms such as Flickr, Pinterest or Instagram are chocka full of images captured on film and scanned so as to be presented to an eager global audience. To some degree this might be viewed as a hipster fad, but it goes deeper than that. It’s a sign of the times that the choice of photographic films available in the marketplace is greater than it has been for decades. Prices for used cameras are rising constantly, camera techs (those who survived the digital revolution) are busier than ever, new businesses are cropping up that want to claim their stake in the new analogue world. Of course, this development is far from mainstream; it might be likened to the vinyl market – consumers stream their muzak, fans are buying records again.

What’s new about this reemergence of film photography is the fact that the vast majority of photographers combine the analogue with the digital, in that they scan their negatives, edit them on their computer screens and post them online. Actually printing their work, however, does not even enter the picture (silly pun intended). And this is where I would like to make a bold statement: Not committing your pics to paper in your own darkroom is a serious omission! It’s like playing a guitar with only two strings. It’s possible, but why do it?

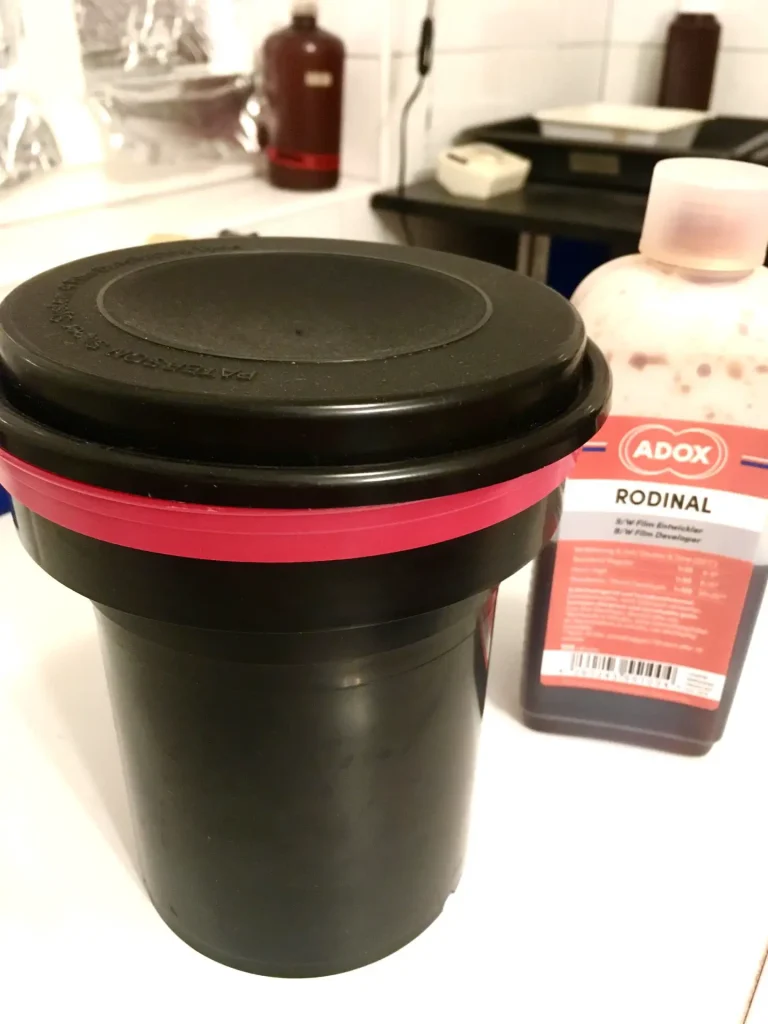

I truly believe that 75% of the artistic work entailed in making a great photo takes place in the darkroom. It starts with the development of the film and the whole alchemy/voodoo behind it. It’s at this point where you commit to the contrast range of your image, the “oomph” if you like. And it’s such a personal thing, I would hate to leave it to a lab that, necessarily, does a one-size-fits-all job. Only I know the lighting conditions in which my images were shot, only I know I have to give this particular roll a one-and-a-third-stop push in a speed-increasing developer, and this other roll, shot at box speed, I want to be developed in Rodinal for an increase in grain sharpness.

It doesn’t end there, of course. Now that you have your negs all dry and shiny, you want to view them as positives. Yes, you could throw ‘em on the scanner and be done with it, but in my opinion, you’d be missing out on the best bit!

Enter the darkroom, your artistic studio, where the magic happens! You start by printing a contact sheet of your negatives. How old-fashioned is that!? You put your negs on some photographic paper, under a sheet of glass, and expose the paper in such a way that you just about get maximum black from the unexposed bits of your negatives, i.e. the edges and gaps between the exposures. Why, you might ask? Why not go ahead and make real prints straight away? I’ll tell you why: A contact sheet tells you all you need

to know about the inherent contrast of your negs and the exposure levels of individual shots. What’s more, it also teaches you a great deal about the way you expose your films and how you should develop them. Do you constantly underexpose? You might want to look at how you meter your subjects. A contact sheet will also assist with estimating exposure times and contrast filter choices once you have got to know your specific enlarger like the back of your hand. Lastly, a contact will give you the opportunity to evaluate your shots without having to make individual prints of all of your exposures on that roll, because, as we all know, the number of exposures on a roll of film worth printing may actually be shockingly small.

I assume now you are dying to make a real print, so you stick your chosen negative in the enlarger’s negative holder, adjust your easel for the required paper size and focus your image. Viewing the enlarged negative reflection on your white base board will again provide important information about the print contrast required for that particular image, so you can take an educated guess at what filter to dial in or place in the filter holder, depending on your enlarger type. You could now make an exposure test on a strip of photo paper with incremental exposure times, or, if you’re well acquainted with your enlarger (and your negatives are exposed consistently thanks to what you have learnt from your contact sheets), simply do a single exposure on a test strip covering both highlights and deep shadows in your image at an estimated exposure time.

Develop, stop and fix your strip, wash it for a few seconds and turn the white light on: Is there any information in the shadows? Is the contrast how you like it – is the punch there like in the images of the old photojournos whose look you’re trying to emulate, or does it have the “glow” of Ansel Adams’ iconic photographs? Well, now is the time to adjust the settings on your enlarger and go for a proper print. Dev, stop, fix and wash. Admire your work of art. Frame it. Scan the print and release it into the World Wide Web. (For giggles, you might want to scan the negative, too, and compare it to the scan of the print. Be surprised at the tremendous difference in depth and grain structure in favour of the scanned print!)

Of course, you could say that all this creative work could easily be performed in Lightroom straight from your scanned negative, and apart from the different “look and feel” inherent in scanning a print rather than a neg, this is true. In fact, working in photo editing software can achieve so much more than darkroom work, which can give rise to sloppiness and carelessness when taking photographs, because “things can be fixed in the computer”. In that sense, darkroom work is also about limiting yourself to some degree, which, ideally, will get your creative juices flowing. The Beatles recorded “Sgt. Pepper’s” on a four-track tape machine; today, there is no limit to the number of tracks one can record on on a computer system. Yes, some good(-sounding) music is recorded today, but the sheer amount of great music that was recorded on supposedly primitive analogue equipment is mind-blowing compared to today’s high-tech output.

The personal, artistic satisfaction gained from making a tangible end product employing a range of time-honoured techniques and skills acquired over time should not be underestimated. Shooting on film and scanning your (perhaps lab-processed) negatives may be somewhat more involved than shooting digitally, but you still essentially bulk process all or most of your photographs and store them on a hard drive. As a darkroom printer, however, you tend to focus on your best work only, and since you spend so much time (relatively speaking) with individual images, you will fondly remember each one, even if it doesn’t make it to your dining room wall. Well, there’s always the good old-fashioned photo album. Remember those?

As a photographer I have only felt “complete” since I started developing my own films and printing my own images in the darkroom. It is so much part of my workflow now that I couldn’t do it any other way and still be happy with my images. My darkroom work has a profound influence on my photography and vice versa. At the end of the day, it’s about “taking back control”, to borrow a very tired, overused slogan.

Visit Recky on Instagram at reckys_film_lab

Share this post:

Comments

thorsten wulff on Why I Think You Should Print Your Black & White Negs In Your Own Darkroom – By Recky Reck

Comment posted: 11/12/2019

Bruno Chalifour on Why I Think You Should Print Your Black & White Negs In Your Own Darkroom – By Recky Reck

Comment posted: 11/12/2019

Because I started developing and printing my own film (bw and color, C-prints and Ciba/Ilfochrome included) and moved without regret to digital when it became superior and more convenient than analog black and white (control, D-max,...), there is no aura involved for me, just facts. If I may go back to my darkroom it is just because I have still got some frozen film left and film cameras that still do the job but to be honest, it is not my first choice anymore my main interest being more in the result (the print whether analog or digital) than the process. Thank you anyway for this eloquent testimony.

Zvonimir on Why I Think You Should Print Your Black & White Negs In Your Own Darkroom – By Recky Reck

Comment posted: 11/12/2019

Equipment-wise my chief hope is that someone starts building coldlight units for enlargers again. The pictures that these produce are far superior to those from diffusion or condenser units IMHO.

Comment posted: 11/12/2019

Daniel Conrad Sigg on Why I Think You Should Print Your Black & White Negs In Your Own Darkroom – By Recky Reck

Comment posted: 11/12/2019

Sincerely,

Daniel

David Cuttler on Why I Think You Should Print Your Black & White Negs In Your Own Darkroom – By Recky Reck

Comment posted: 11/12/2019

If you like the process then go ahead and invest in building a darkroom.

Comment posted: 11/12/2019

Charles Morgan on Why I Think You Should Print Your Black & White Negs In Your Own Darkroom – By Recky Reck

Comment posted: 11/12/2019

Daniel Castelli on Why I Think You Should Print Your Black & White Negs In Your Own Darkroom – By Recky Reck

Comment posted: 11/12/2019

Thanks for a timely article! People should go out and buy darkroom gear now before Christmas Day!

I'll toot my own horn...(because I don't know how to do the linky thing directing people to an article) I wrote an article on this self-same site on my darkroom. Go to Musing on the top, then Technical Knowhow and you'll find the article. Don't worry about my inability not to figure out how to link...when our daughter comes home for Christmas Holiday I'm going have her teach me how to do it.

Dan Castelli

Comment posted: 11/12/2019

Huss on Why I Think You Should Print Your Black & White Negs In Your Own Darkroom – By Recky Reck

Comment posted: 11/12/2019

And that is the beauty of the hybrid workflow - it is very democratizing. It allows people to shoot film, develop it, scan it, print it (albeit not in a darkroom) and just enjoy film. Without wondering where they would put a darkroom in their studio apartment!

Janne on Why I Think You Should Print Your Black & White Negs In Your Own Darkroom – By Recky Reck

Comment posted: 12/12/2019

But a darkroom with an enlarger is a whole different thing. Unless you live in your own house or large apartment it will be difficult to impossible to make a set-up that will actually work in practice. You could jury-rig some setup in a shower perhaps; dragging in a small table, taping up a light-proof curtain and so on, but really: a darkroom that needs hours of setup and tear-down every time is a darkroom that will go unused.

Scanning your film is a fine way to enjoy and share your images. You don't have to have the space and time for a darkroom to be a "real" film photographer.

Michael McDermott on Why I Think You Should Print Your Black & White Negs In Your Own Darkroom – By Recky Reck

Comment posted: 12/12/2019

Recky on Why I Think You Should Print Your Black & White Negs In Your Own Darkroom – By Recky Reck

Comment posted: 12/12/2019

As a B&W photographer you owe it to yourself to at least try printing your own negs!

Daniel S on Why I Think You Should Print Your Black & White Negs In Your Own Darkroom – By Recky Reck

Comment posted: 12/12/2019

Nick S on Why I Think You Should Print Your Black & White Negs In Your Own Darkroom – By Recky Reck

Comment posted: 13/12/2019

Comment posted: 13/12/2019

Rob Phillips on Why I Think You Should Print Your Black & White Negs In Your Own Darkroom – By Recky Reck

Comment posted: 02/01/2020