In Eric’s recent article, “Olympus Camedia C2020Z – Vintage Digital/Antique Shop ‘Jankuary’ Find – 2MP from 1999″, about a camera that he had found in an antique shop there was a photo which showed the sales ticket with the note “sensitive to IR”. This immediately rang bells with me and my 25 year old Olympus C2000Z came out of the cupboard.

I have long been fascinated by infra red photography, using Rollei Infrared 400 film, digital and software manipulation. It was fortunate that when I bought my C2000Z new in 1999 I also bought the accessory lens adapter tube/stepping ring which allows for attaching lens accessories such as supplementaries, close up lenses or a lens hood. My IR filters will therefore fit to it with stepping rings.

It seemed reasonable to suppose that the sensor on my camera would be the same as the C2020Z and so it proved.

The main problem, however, was the same as Eric’s, namely how to get the files off the now defunct Smartmedia memory card and into the computer. My Microtech USB Cameramate reader would no longer work and the camera’s dedicated USB cable was lost some time ago so the solution was to buy a new, multi-type reader.

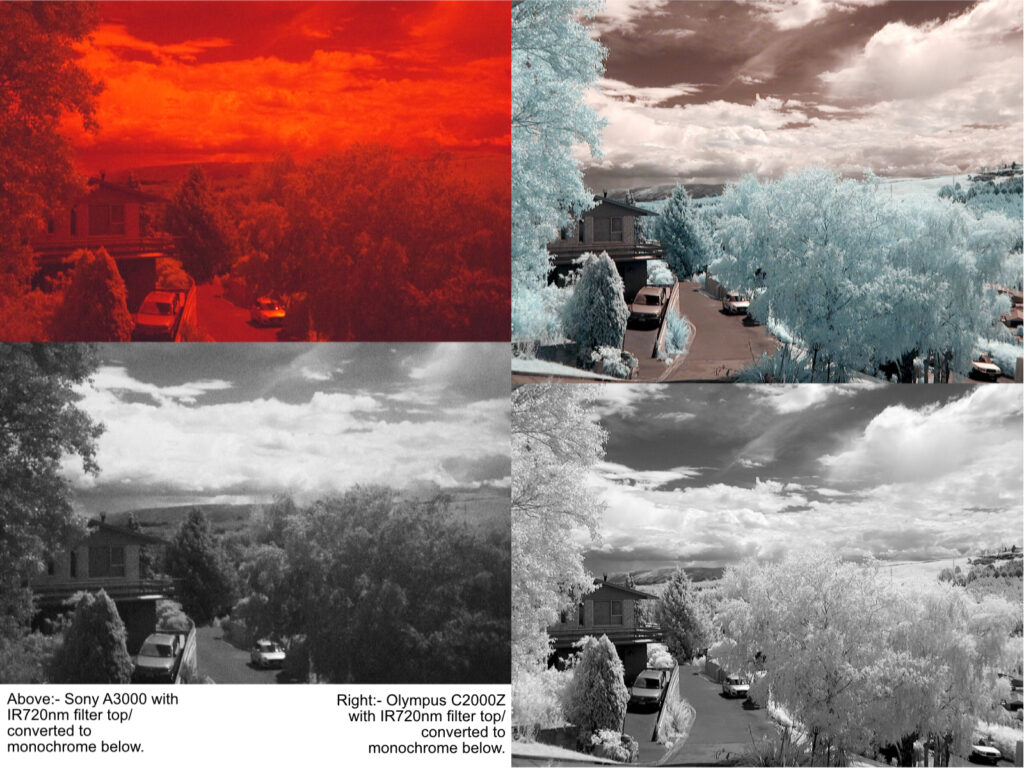

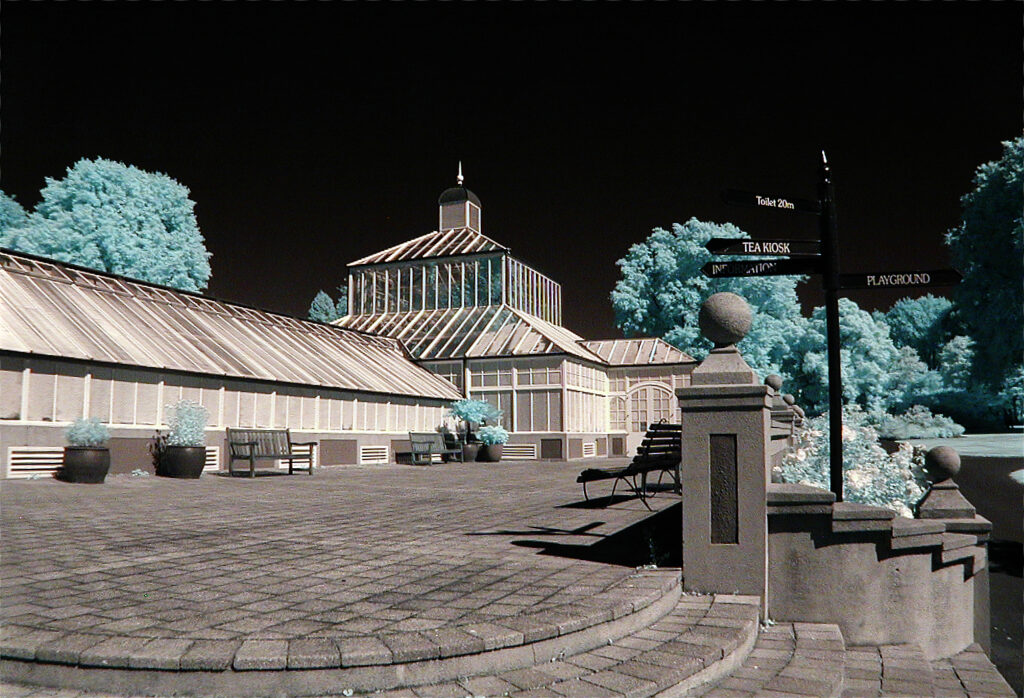

I had to wait a tantalising three weeks for this to arrive with the test images only visible on the camera’s rear screen, all 1.8” of it, but they were very encouraging, with pleasant colours. The same shots on my Sony A3000 required a longer exposure and are overall red because of the much stronger built-in IR filtration and really need to be converted to mono. The infrared effect is not as strong either even when in mono though I have produced some good results with it. The ones from the Olympus have pleasant, pastel colouring and some can stand as they are as well as in mono.

The Olympus C2000Z

The camera is a very capable device and when new was praised for its comprehensive controls, flexibility and compactness. At 300dpi though it would only print to 5”x4”, a drop in resolution was needed for anything larger. I seem to remember some software interpolation for larger prints was offered in the included software, also lost. Still, it taught me a great deal about the digital world and the size limits led me to learn even more about manually stitching images in software. Results in terms of sharpness and colour were very good, some of the best at the time, but the need to refine the design overtook it in mere months. In its very short day in the sun, though, it was up there with the best. Digital Photography Review’s web site has a comprehensive review of the model.

It has a 2.1Mp sensor and Program, Aperture and Shutter Priority modes with a panorama setting that needs the included Olympus card to work, something I never tried, and playback. Buttons are largely confined to menu and playback navigation on the small screen. Zooming is controlled with a stubby lever on the front edge of the top plate with the shutter release in its centre in front of the mode dial which has the on/off button in its centre. The finder zooms with the lens and has warning LEDs and a dioptre adjustment. These early cameras were really power hungry, especially using the rear screen. No doubt this was the reason Olympus provided the optical finder and small info screen on the top plate so the rear screen was needed less.

The menus are not up to today’s standards but the most annoying feature is the on/off button, located just where your finger naturally seems to rest. I lost so many shots through turning the camera off instead of pressing the shutter release and I still do it. Reviews also criticised this annoying feature and it was moved to a click stop position on the mode dial along with a few other tweaks just a few of months later when Eric’s C2020Z appeared to replace it.

Another niggle some reviewers complained about was the battery door which is without a doubt pretty hard to close. I find that pressing firmly where Olympus suggest, on a dimpled circle, is effective and not a problem.

Into the infrared

The reader having arrived and checks on the test images showing promise I set out to capture some more. This is easier than with the grainy, indistinct Sony screen or evf and, because an optical finder is not affected by the filter, is more like using IR film in my Retina IIc but with no need to adjust focus to an IR mark and with auto exposure. Back in the day I tended to use TIFF SHQ for maximum quality but I find that SHQ jpegs are hardly any different providing 32 frames instead of only five per 32Mb memory card. TIFF is always available if needed.

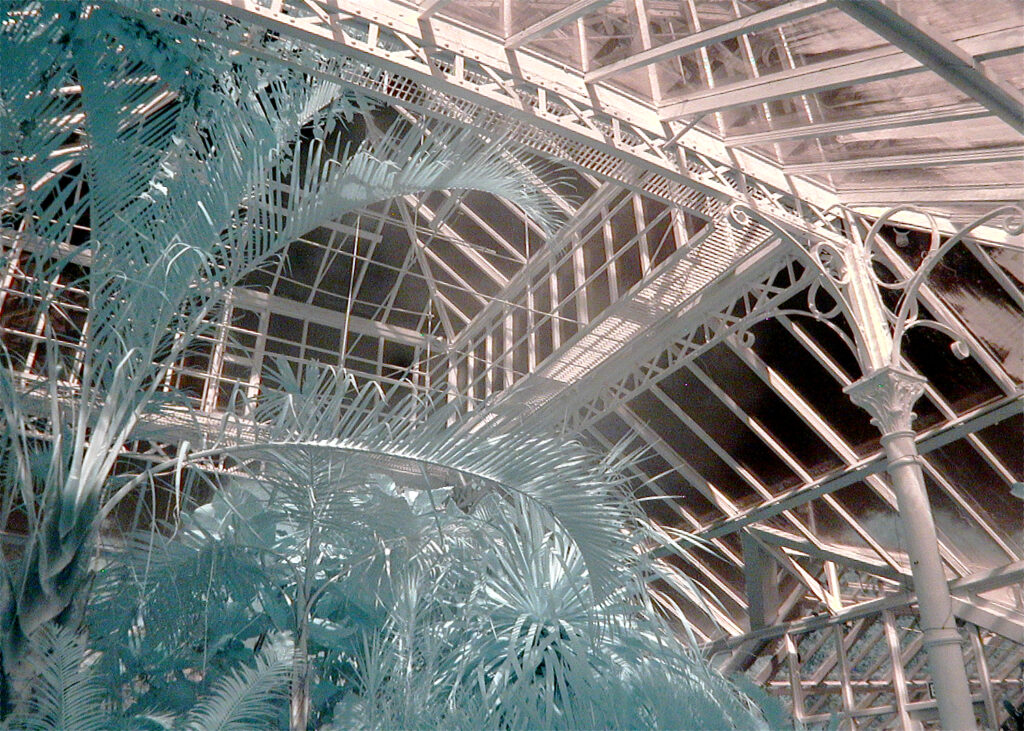

I still have a wide angle and a fisheye supplementary bought a while ago so I took a few frames with them. They both have 52mm male threads so I mounted them on top of the R720 filter preserving the IR capture ability. They take the edge off the definition but not to a disastrous degree. The wide angle shows just noticeable barrel distortion which requires only a small amount of correction.

Lessons learned

Going back more than 20 years was an eye opening experience I must say.

By far the biggest surprise came from how slow it all was back then. Writing a SHQ jpeg to the card seems to take an eternity though only 4 or 5 seconds. A TIFF on the other hand takes over 40 seconds which seems like forever. We are so spoiled nowadays aren’t we?

The next thing to strike home is the inaccuracy of the optical finder, its axis is several degrees off centre and includes far less of the image than is recorded. As a result I had to frame very tightly to make the most of the meagre 2.1 megapixels on offer and also aim slightly to the left. I noticed the fisheye images were not centred on the sensor as you would expect which may have something to do with the sensor and finder not being in sync.

And then there were the hot pixels I had completely forgotten about. It quickly came back to me, having to spot out these multi-coloured dots that would appear randomly anywhere in frame. Not many but usually noticeable.

But…

I was more than happy with the images, especially the “straight” ones without the supplementaries. I know that they are somewhat crippled by having such a small pixel count. But for on-screen use and small print sizes they are very acceptable. It almost makes me start looking for a Sigma SLR or an adapted modern digital. Will it ever end. I certainly hope not.

Share this post:

Comments

Uli Buechsenschuetz on Olympus C2000Z – A new life for an early digital compact

Comment posted: 12/04/2024

Comment posted: 12/04/2024

Geoff Chaplin on Olympus C2000Z – A new life for an early digital compact

Comment posted: 12/04/2024

Comment posted: 12/04/2024

Comment posted: 12/04/2024

Comment posted: 12/04/2024

Herb Kateley on Olympus C2000Z – A new life for an early digital compact

Comment posted: 12/04/2024

Comment posted: 12/04/2024

Comment posted: 12/04/2024

Gary Smith on Olympus C2000Z – A new life for an early digital compact

Comment posted: 12/04/2024

I love the shot called: "Cranwell churchyard in winter" as well as "Tropical House Botanic Gardens Dunedin with wide-angle supplementary". Some years ago I had my gx85 converted to 590nm IR but I never seem to take it out with me enough.

Comment posted: 12/04/2024

Ibraar Hussain on Olympus C2000Z – A new life for an early digital compact

Comment posted: 12/04/2024

Fantastic photographs from this little fellow!!

Thank you!

Comment posted: 12/04/2024

Wes Hall on Olympus C2000Z – A new life for an early digital compact

Comment posted: 13/04/2024

Comment posted: 13/04/2024

Roger on Olympus C2000Z – A new life for an early digital compact

Comment posted: 14/04/2024

My main question relates to exposure times. I understood that the reason why digital cameras had to be converted for IR was that they contained a filter that blocked out IR and UV light, meaning that if you filtered out all visible light, the result would be very long exposures. Were the exposure times similar to those using visible light or were they much longer, requiring a tripod?

Comment posted: 14/04/2024

Toki on Olympus C2000Z – A new life for an early digital compact

Comment posted: 10/05/2024

Comment posted: 10/05/2024

Adam on Olympus C2000Z – A new life for an early digital compact

Comment posted: 20/06/2025

I think I'll have to track down one of these cameras now :)

Could you please tell me how large the filter size goes up to on the adapter?

Thanks

Adam

Comment posted: 20/06/2025

Comment posted: 20/06/2025

Comment posted: 20/06/2025

Comment posted: 20/06/2025