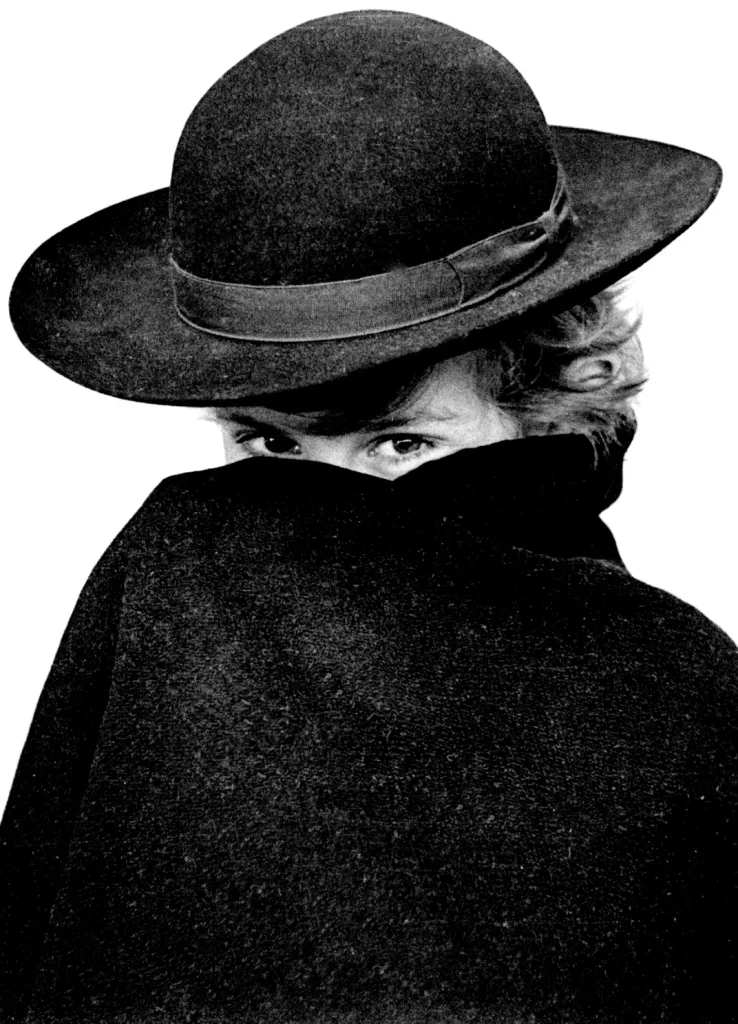

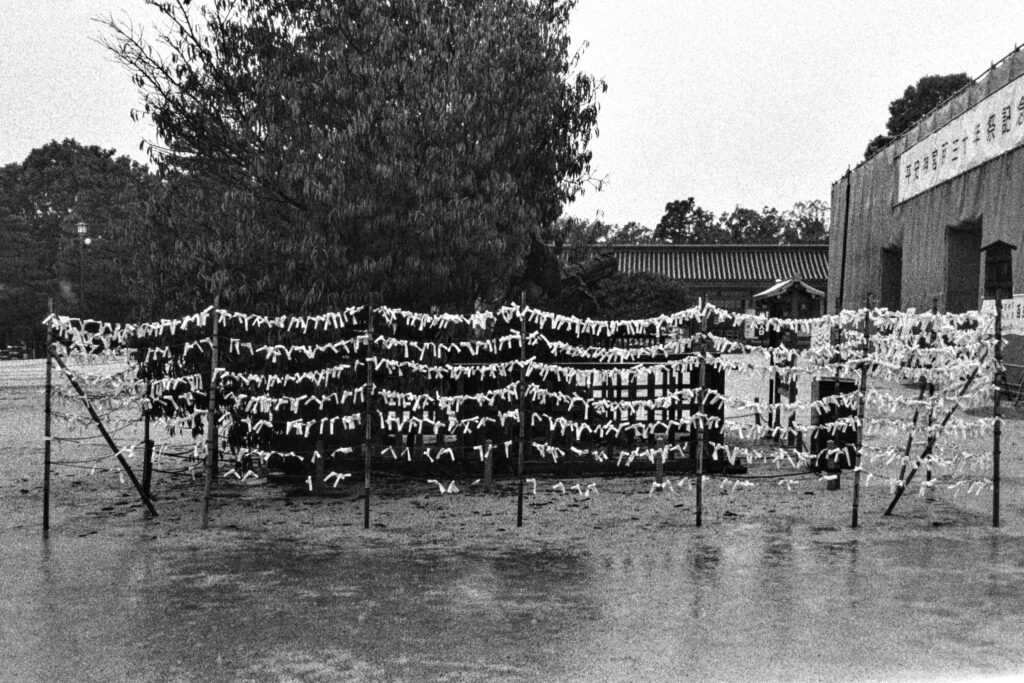

My analog gear has been sitting in a closet since I started experimenting with digital cameras. However, when looking for images and inspiration, I keep on visiting blogs and sites that showcase analog images – like the one you are reading now. Black and white, grainy, gritty images: who cares for color or the clinical precision of digital cameras…?

I like to think of myself as a guy with a camera, not a photographer. My taste is locked in the last century, my mindset still constrained to the 24/36 exposures limit. Taking a lot of images is expensive (I am not talking only about money) even in digital. I usually return home with no more than a handful of pictures.

When reviewing photos right after the fact, I always feel like they are “wasted pixels”. Cannot recall a time when I took a photo and had the feeling that it will be a keeper. Better to turn off automatic review and pretend that images must be developed later.

Assuming I’m talking to like-minded people – even though here little or no film is used – I would like to share my experience with what I call my Steampunk Photo Paper. Dull whites, low d-max, high price: too good to be true? The images that follow might convince you too.

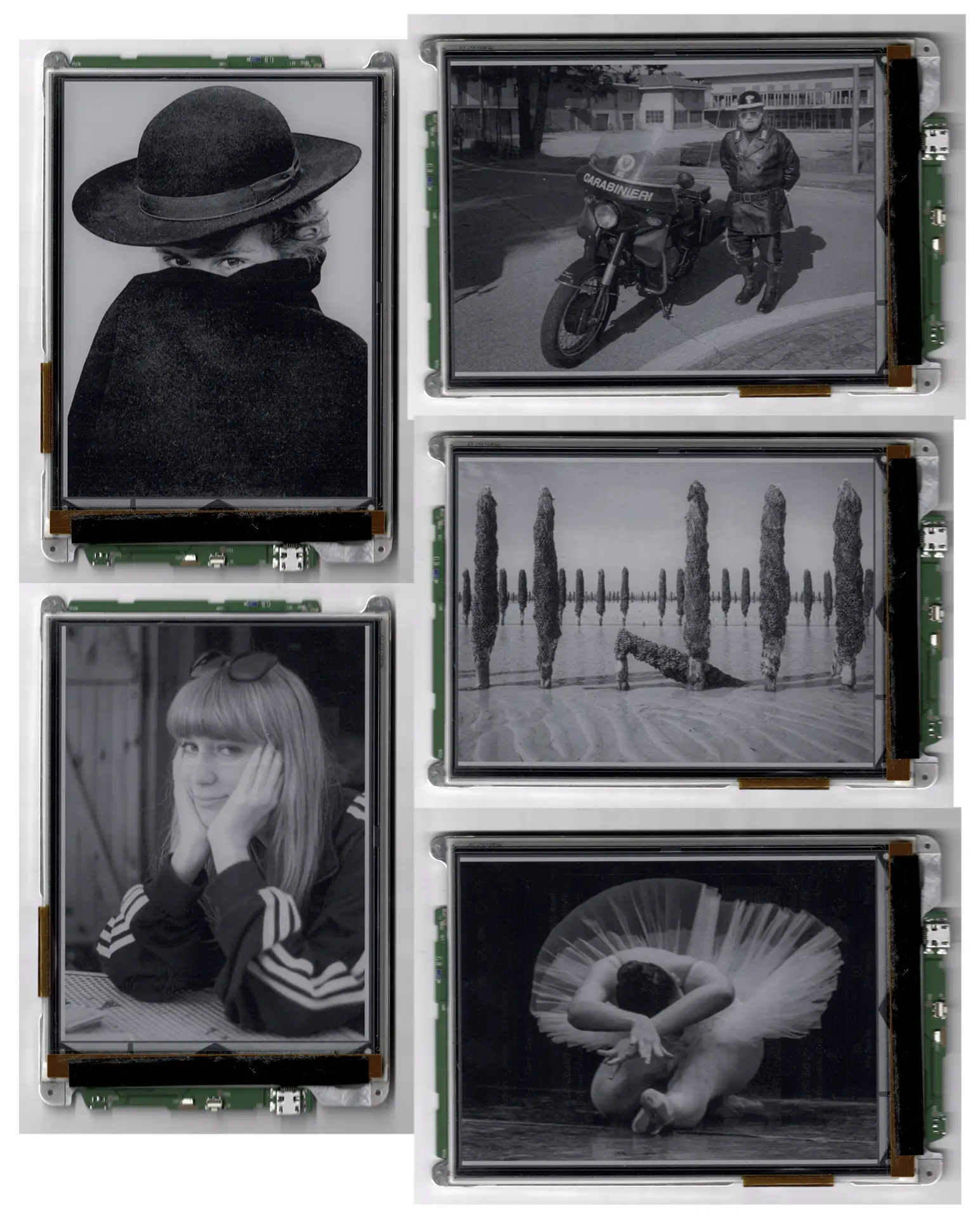

Jokes aside, the above images are down-ressed, down-sampled files ready to be displayed on e-paper screens. The idea is intriguing: infinitely reusable photo paper and no batteries needed after the image is “printed”.

Taking advantage of the Razor and blades business model, I realized that buying and hacking an ebook reader was cheaper than acquiring the needed parts separately: I guess that ebook companies try to lure you in their ecosystem to profit on digital content…?

With almost no software trickery and some bricolage, I assembled a small tabletop digital photo frame that most people cannot tell from a low-quality vintage silver print.

How-to

The ebook reader I used is a Kobo Clara. The screen is the same quality of the Kindle Paperwhite: the big difference is that the first keeps displaying the current read when shutdown, while the Kindle does not. The standard Kobo software offers an option to keep showing the book cover picture even when the battery is completely depleted.

I removed the device plastic housing, made some cardboard adapters and a mat to fit the device in a standard wooden picture frame.

The success made me think that it is just a matter of time for bigger and brighter epapers to appear at affordable prices. I was really excited when I discovered that there are battery-less epaper displays that wirelessly draw power and data from almost any recent smartphone (using NFC). Changing the picture is a matter of bringing the smartphone near the device and you’re done. Unfortunately, at the time these displays (mainly targeted at shop tags) are limited to black and white images and the resulting quality is much worse than the grayscale screen I used.

It seems that there is a limited market that pushes the evolution of epaper technology and applications. I am not aware of devices with more than 16 grey levels. Also, forget about color.

If you are interested in trying, the preparation of the files to be “printed” requires additional steps after you edited the image to your liking:

- Crop and resize to 1072×1488 pixels (the epaper resolution)

- If image is in landscape format, rotate 90 degrees (ebooks are usually set in portrait mode)

- Add a posterization layer with 16 grey levels (assuming you are using a 4-bit display)

At this point it is possible that these modifications introduced some artifact (like abrupt transitions in smooth gradients).

Images might then require further adjustments such as blurring and adding noise (to smooth the gradients when using fewer grey levels) to some areas or the entire image.

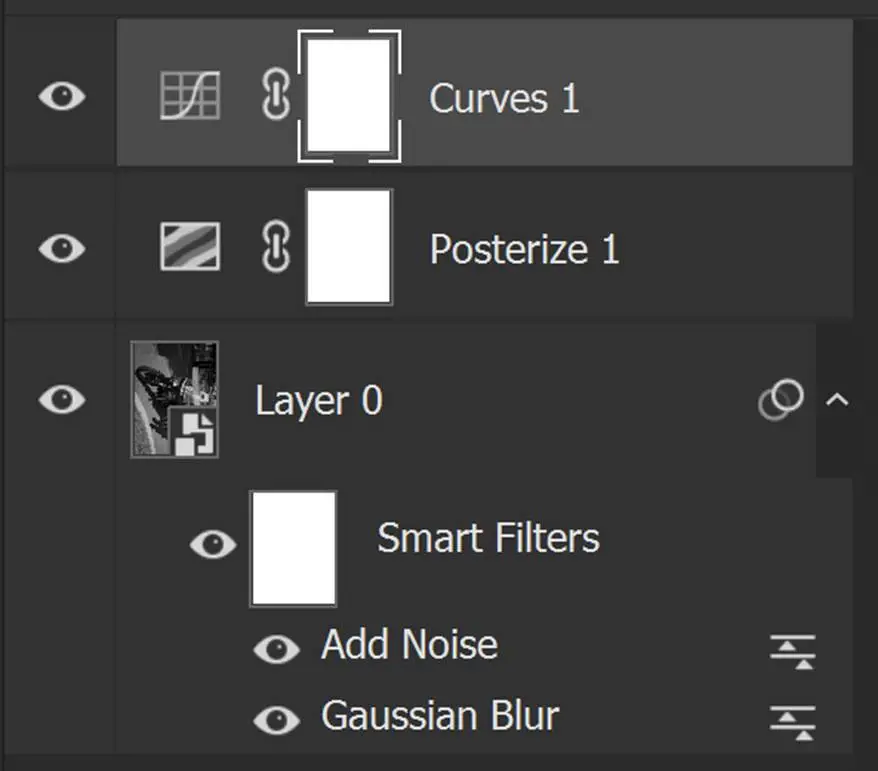

This is the Photoshop layer structure of the policeman image:

Without considering the different brightness levels of computer screens and epaper, this is sort of WYSIWYG because you are playing with the same pixels that will be printed. Getting a pleasant brightness (the curves layer above) is more trial and error.

Finally, image files are not ebooks: in addition to the standard ebook formats, some ereaders are able to show comic books. The CBZ (Comic Book Zipped) format is nothing but a renamed zip file that contains a cover and one or more jpg files. The first image in the file is the book cover and shown when the device is turned off (this option is configured in the settings page). A second jpg file is needed by the reader software to assume that there is something to show.

CBZ files can be transferred to epaper via USB cable. Alternatively, you can also transfer them by sending bytes all around the world using the ereader company cloud services and the WIFI connectivity of the device. Once the files are in the epaper storage, you select the one to be displayed as you would select an ebook to read, shutdown the device, close the enclosure and enjoy the result.

To give an idea of what to expect in terms of brightness and tonality, I scanned the prints with a flatbed scanner (they are prints, after all):

Thanks for reading my report and looking at the pictures.

Post Scriptum: of course, I am not the first or the only one that played with these things. You can also check:

- How to open Kobo ereader without destroying it (skip to 11:15) : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sxqVLnosNTI

- If you are interested in hacking the Kobo software: https://yingtongli.me/blog/2018/07/30/kobo-telnet.html

- If you want to leave the fun to someone else: https://framelabs.eu/en/

- If you want to do it the hard way: https://hackaday.com/2020/10/30/color-e-ink-display-photo-frame-pranks-mom/

- Ready to use true NFC epaper, unfortunately no grayscale (I do not have any relationship nor had bought anything from them, yet): https://www.waveshare.com/7.5inch-nfc-powered-e-paper.htm

Share this post:

Comments

prur on Epaper Photo Printing – My Steampunk Photo Paper – By Marco Dughera

Comment posted: 14/01/2021

Daniel on Epaper Photo Printing – My Steampunk Photo Paper – By Marco Dughera

Comment posted: 14/01/2021