Over the past five years or so I have been delving deeper and deeper into subminiature formats, 110 in particular. This has aways been an area of photography that I had sidelined as snap-shooter territory but which has become a near obsession as I discovered the wide range of options available. I have discovered that the cameras combined with modern emulsions and digital post-processing could produce amazing image quality for their size and the cameras themselves are a pleasure to use with a charm all of their own.

Putting this into context, the compilation of negatives shows hw small these formats are to be able to produce creditable images.

An introduction to 110

The 110 camera system was introduced by Kodak in 1972 and has seen an increasing revival of interest lately. The main stumbling blocks have been film and batteries (when needed). Lomography to their credit have solved the film issue at the commercial level and the now banned or obsolete batteries can be worked around in most cases so the format is still a viable option.

Batteries are needed for the more advanced models with exposure metering and/or motor drive, but some will operate in manual mode. Mine vary across the board from the Minolta 460 Tx that works fully manually to the Minox 110S which will not work at all without power even though it may seem to be working. The shutter fires but is capped until power is available to set the speed established by the meter.

The film

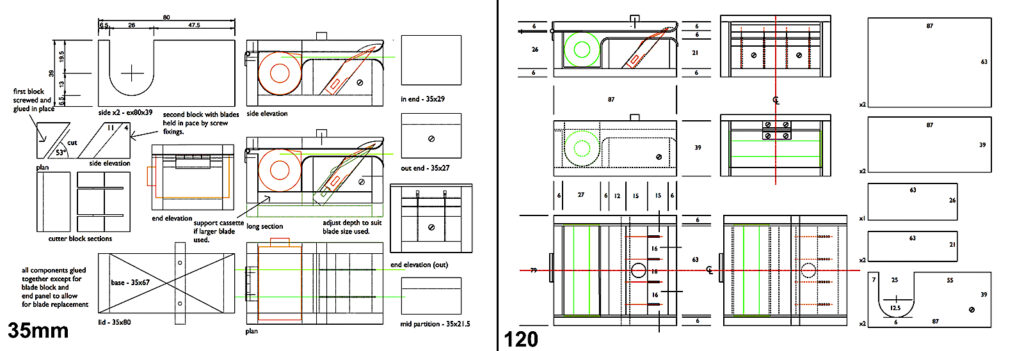

Negatives from these tiny cameras are very small of course, the standard, commercial 110 frame measuring 13 x17 mm, 1/4 the area of 35mm, similar to Micro 4/3, pushing film resolution and grain to the limit. There are many monochrome films available these days though which are based on surveillance originals that offer very fine grain and sharpness and offer an alternative to commercial 110. But to use them it is necessary to slit strips 16mm wide from 120 or 35mm stock. Suitable devices are available commercially or can be made if you are fairly handy. I will supply drawings for my 35mm or 120 DIY versions if anyone wants to try their hand. The 120 version shown does not need a donor body like my original one.

The camera too has a part to play, the feeler that springs into the single perforation of commercial film to control spacing is often used to interlock with the shutter or other functions. Some models will simply not work at all with anything other than a dedicated 110 film in place. In general terms, if a shutter will fire without film and with the back open it should work with unperforated film though spacing may be wider and a few less frames achievable for a given length of film.

Film processing can be trade or home. The only thing required will be a suitable spiral for processing at home. There are a number to be found on line or it is not too difficult to modify a standard one.

The cameras

I will leave details of the cameras to sites that cover this subject extremely comprehensively. Recommended examples are The Subclub (http://www.subclub.org/index.htm) and Submin (http://www.submin.com), both dedicated to all things sub-miniature. You can find a review of the ones in my care on this site if you click on my profile below along with other related posts and those of other contributors to 35mmc who have also covered the topic if you put “110” into the search box.

Like 126 before it, the 110 camera was originally developed by Kodak as a small, simple camera that required little photographic knowledge and removed all the technical aspects, even loading film. Several other camera manufacturers took up the idea and produced their own versions. At introduction, they tended to have a fixed focus lens, a couple of apertures and a single shutter speed to keep things as simple as possible plus flash capability. As the format became accepted, however, more experienced photographers wanted a bit more control and designs became more sophisticated, leading to better quality, focussing lenses, wider exposure control and built-in flash and motor drive in some cases. The Pentax SLR even had interchangeable lenses.

A browse through the sites mentioned will show the whole, intriguing range in detail.

110 cartridges, the sequel

( I have omitted any adhesive tape for clarity in the following examples. When in place the sections fit more snugly together.)

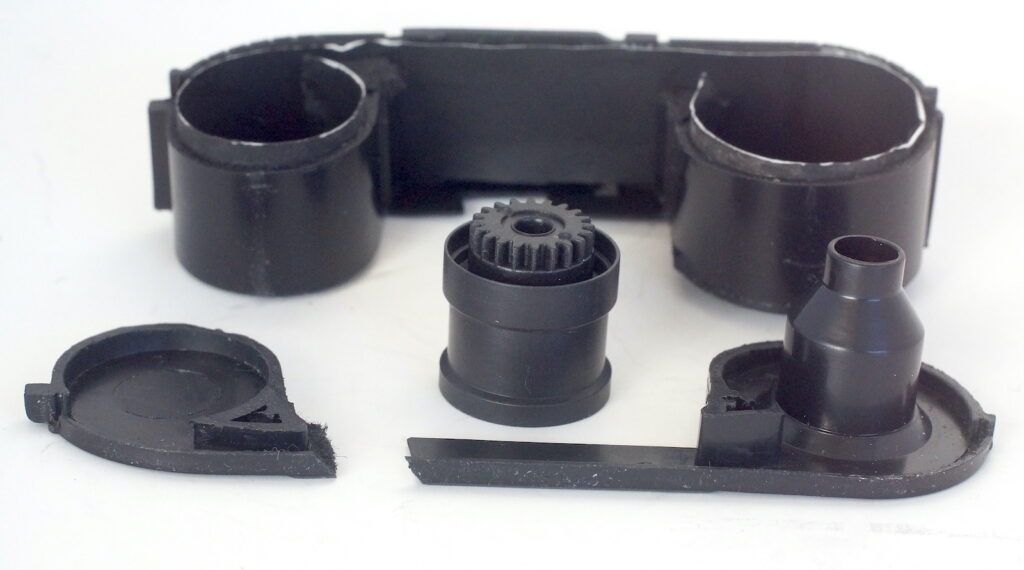

Once film strips have been acquired, a means of loading them into the camera is needed. The 110 cartridge is a self-contained unit holding the unexposed film and the take-up spool in one unit and is geared to the camera to drive the film across the gate. Loading is simple with no threading needed, just drop the cartridge into place, it will only fit one way, and close the back. A Kodak preoccupation with simplicity and led to 126 before 110 and the disc system after it.

Fortunately, these cartridges can be opened carefully and re-used, though opening them can lead to some light trap weakness, particularly around the curved sides of the film compartments. So far I haven’t found anyone making a 3D printed version but that would be very welcome.

As mentioned, the standard frame size is 13 x 17 mm with commercial film stock. The benefit gained from reloading cartridges is that the camera gate opening is usually around 19 x 13.5 mm which is what appears on film but is masked down with commercial stock. The down side is that the viewfinder is not an exact match but tight framing will get over that. A little less magnification is needed for final output and some cropping is also possible. A little vignetting can appear with some lenses at infinity focus and/or large apertures but it is minor.

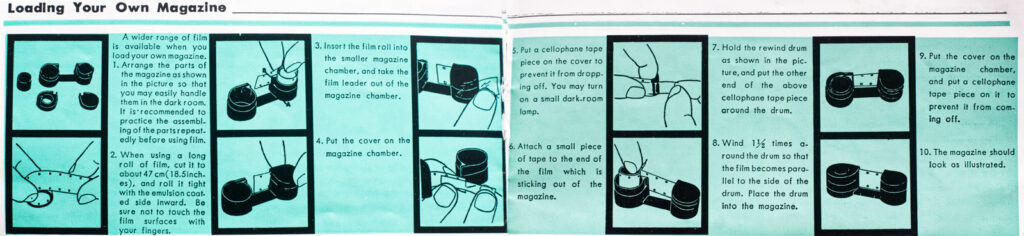

As well as 110 I use 16mm film in a Minolta 16MG. This uses a cassette, operating on the same principles as 110, i.e. self contained drop-in loading with connected feed and take-up drums, each with its own cap, and an integral connection to the drive mechanism for film transport. This provides the same drop in simplicity for loading. Its other big advantage is that it is designed from the outset to be reloaded by the user. Once the feed roll is in place with a tongue protruding and the cap secured in total darkness, the rest of the reload can be done in subdued light.

Following on from my early efforts at re-using the cartridges an article by Bob Janes on his efforts at perfecting them for re-use led me to try out a couple of his ideas quite successfully, one of them in particular striking a chord.

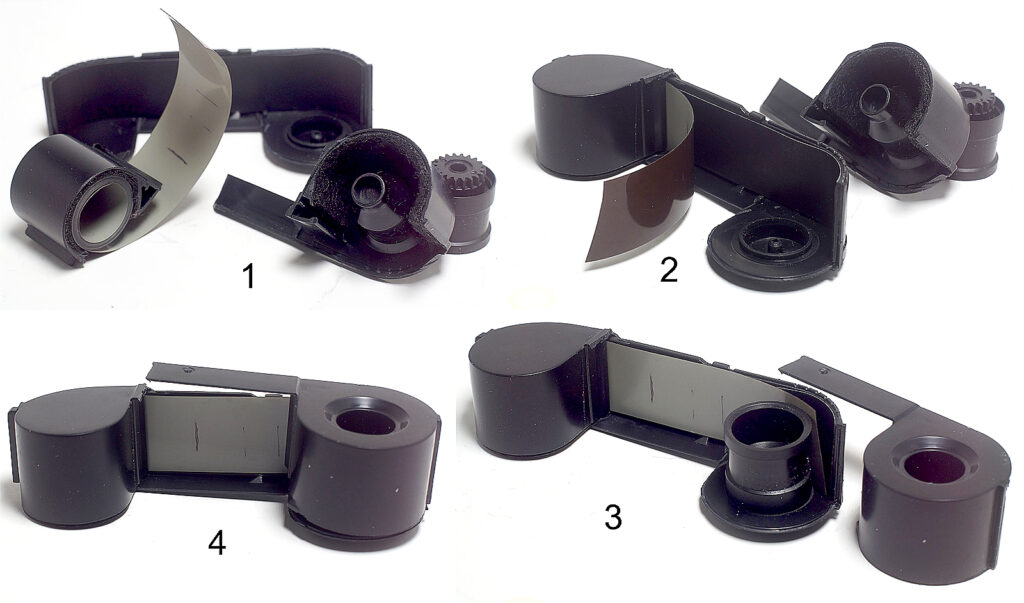

One of Bob’s ideas was to modify the 110 cartridge to be loaded in the same way as the reloadable Minolta 16mm type described above. In his version the top section is cut in two so the feed roll can be capped and the take up side completed in subdued light in the same way as the Minolta. His other improvement was to cut the film drums in half and glue the lower half permanently to its seating. These curved, lower joints are the weakest points after opening the 110 unit and then by lining the cartridge with backing paper a positive light-tight seal is made.

Further cartridge development.

Building on this idea, I cut a cartridge higher up which worked well from a loading point of view combined with the split top section. I did get a little light leakage at times where the top is cut which I traced to the back door window. Covering this window cured the problem.

In a later experiment, I tried to devise a means of avoiding a lot of cutting and the wear on the exposed backing paper forming the lip. By lining the bottom section with felt and the top with backing paper I was still able to cut the top in two to allow for easier loading but that was the only cut needed. Most of the original light trapping is retained and the felt reinforces the light trapping at the curved joint. It also made loading the new film more like the Minolta cassette as my sequence below shows.

Output

Processing is no different to any film, a suitable reel or adapting an existing one is all that is needed as mentioned above.

Getting the small image from the film can be tricky. I use a copying set up and macro lens and tubes which is not too difficult to set up or, like the reels, there are various 3D printed adapters available for scanners or to use with a digital camera.

The various films from Lomography can be trade processed and many labs will scan and/or print the negatives too, making it the simplest approach.

Proof of the pudding

With all the angles covered and the little device in the hand the qualities of the cameras can start to be appreciated. The ergonomics are really excellent making handling near perfect. Everything falls neatly under fingers and thumb, both elbows braced into the sides in landscape format, like holding binoculars. In the same way that the mobile phone is mostly held naturally in portrait orientation, 110 cameras work best in landscape. In portrait only one elbow is braced and it is very important to avoid covering the lens or meter with a finger. Still not difficult but requiring a little more care.

The Pentax 110 SLR is the main exception being just a shrunken version of its big brothers. Most will be familiar with the form factor though, so just a little more fiddly, and its accompanying system of lenses, flash units and motor drive is very comprehensive.

Size and weight are quite a bit less than larger formats.

So, you can dive as deeply as you choose into the format and with a lot of imaging being for online use these days, quite a practical and economic option. Maybe environmentally responsible too, using less materials. When a good result appears it can be extremely satisfying.

So, give it a go if it appeals. It is surprising what it can produce.

If you would like to read more about shooting 110, you can find another article about shooting 110 by Bob Janes here

Share this post:

Comments

Jukka Reimola on Enjoying the 110 format

Comment posted: 14/11/2024

Comment posted: 14/11/2024

Neal Wellons on Enjoying the 110 format

Comment posted: 14/11/2024

Your images are beautiful.

Comment posted: 14/11/2024

Bob Janes on Enjoying the 110 format

Comment posted: 14/11/2024

I was surprise bby what you said about the Minox shutter not firing without batteries - I'd been unsure if I had a good connection when I took the shots for my mini-review so operated on the assumption that it was falling back on a 1/40 flash speed - only later did I realise that there were warning lights in the viewfinder which showed if the batteries were good - but you have the beast there, so I guess my reccollection must be amiss.

Unfortunately the 'subclub' seems to have dissapeared - I couldn't find anything with your link or the one I originally put in my atricle - or is it just not visible from the UK?

Comment posted: 14/11/2024

Comment posted: 14/11/2024

Comment posted: 14/11/2024

Dave Powell on Enjoying the 110 format

Comment posted: 14/11/2024

Comment posted: 14/11/2024

Alexander Seidler on Enjoying the 110 format

Comment posted: 15/11/2024

Comment posted: 15/11/2024

Marco Andrés on Enjoying the 110 format

Comment posted: 25/02/2025

Comment posted: 25/02/2025