Just because a lens has a wide field of view doesn’t mean it will be the best fit for an expansive scene. Just because a lens has a narrow field of view it doesn’t mean it’s only good for isolating one thing at a time. Understanding the result you want first, and then fitting your frame around that vision will always be better than using the tools you have to bend reality and manipulate it to your will.

One of the main draws of working with a rangefinder system is the absolute streamline it offers my decision making process. I want my photography routine to involve as little umm-ing and err-ing as possible; instead for my choices of film and focal length to be dictated by necessity and intuition. I don’t want to make compromises about what lens is going on my camera, and which lenses end up in my bag as auxiliary to back that option up. I don’t want redundancies and failsafes and what-ifs based on what a lens offers. My work is story driven, not aesthetic. A backpack with everything from 14mm to 800mm is possible, and maybe makes sense if you’re in a studio, or at the Olympics; for an everyday carry in the city, countryside, commute, and everything else in-between, not so much.

I’ve tried out as many cameras and focal length as I’ve been able, from fish-eye to extreme telephoto at over 1000mm (using teleconverters to achieve this). Even though I know what I want to achieve in my images it’s always worth experimentation. From time and practice, making sure I give second chances when something doesn’t seem to agree with me, I’ve found a very comfortable, very small selection of lenses which give me the results I need without stress. For the tiny fraction of situations where I find I need extreme the reach, or wideness a rangefinder cannot provide I’ll almost always know in advance based on the assignment – I rarely regret not having something in addition to my “three lens solution”, and the times that I have mean lessons learned for the future, which means I know when I encounter them in the future.

Rangefinders start off with some severe limitations inherent to the optical viewfinder. The M3 has only three sets of frame-lines, and unless I’m mistaken, or there’s some special exception, the most you’ll find is six (the M4-P/6/7 with 0.72x finder has 28-90, 35-135, 50–75 frame-lines). Some rangefinders have as few as one frame-line at a time, or even present at all. This is deeply different from an SLR, which is a clear frame onto which can be mounted (and usable as is immediately, without an external add-on) from below even 10mm to effectively a few thousand mm. You could even attach one to a telescope or microscope and be able to make an exposure quite simply. This is great for someone who likes to play with the extreme diversity, to go from photographing a fly’s eye to the majesty of the cosmos (already one and the same), but this is not my practice.

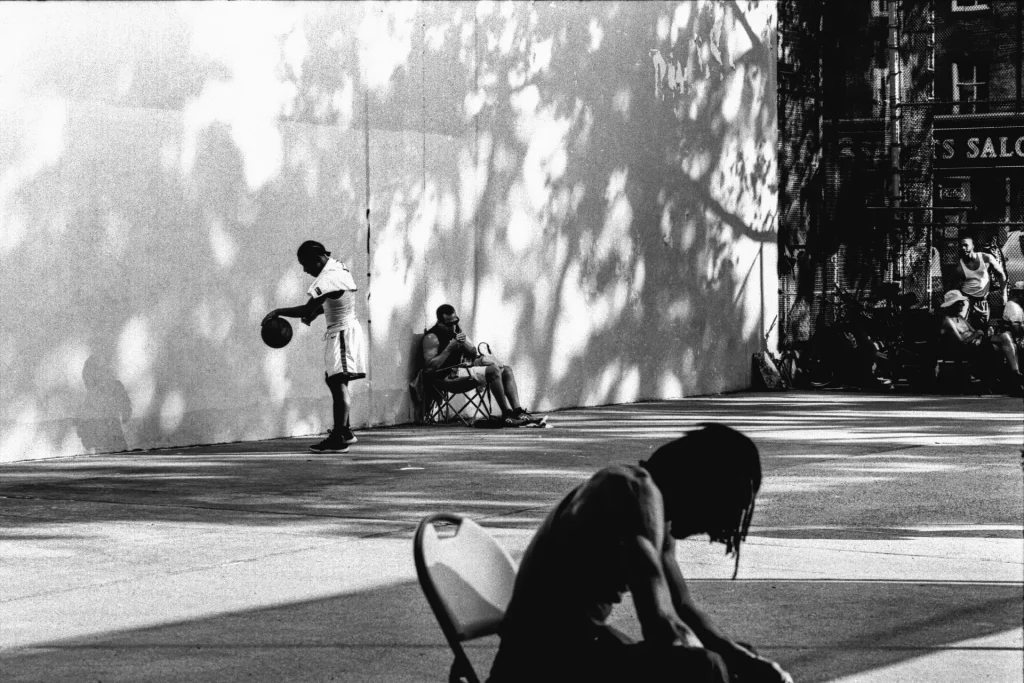

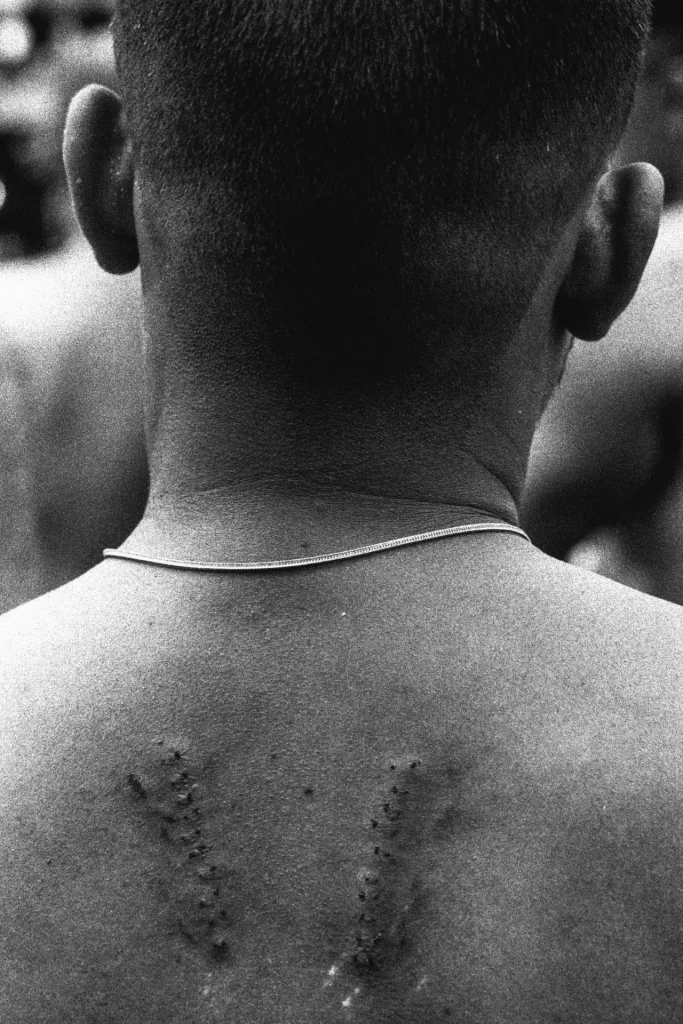

The vast majority of the images I make for my stories will be of subjects between one and ten meters away from me. They will be situations involving people, still or in motion, in groups or alone. I want to be composing around their environment, their relationships with other people, the space they are in, the behaviours and phenomena they are experiencing. An expression on a face, a connection drawn between two people who don’t see one another, a place at the right time or the wrong one.

For this I don’t need micro or macro. I don’t need to be able to count the threads in their clothing. I need to show them clearly, as a real person, not the idea of a person but a tangible relatable human, with a life extending before and beyond me ever pressing the shutter. With these decisions made, focal length is almost trivial. Some of the best photographers I know use only one lens and nothing else. The point isn’t refusing to use anything different, it’s demonstrating that with the right vision any lens you are comfortable can be the right tool for the job.

Coverage within this range means that if I want to step in closer and fill the frame for a portrait/detail I can, and if I want something a little more expansive then I can step away and include more context. This is different to a landscape photographer who must compensate for not being able to go further than a cliff edge allows by using something much longer to hone in on detail. The freedom of being able to move within the space I’m working, and even go outside of it to photograph “into” is essential to the way I like to unfold my photo-essays.

My photographs will be either wide/general view, mid-distance (usually an activity), or close, a detail or portrait. There isn’t a lot that changes about this way of defining things, until you get to the absolute extremes, where you’re photographing that fly’s eye so intently that it becomes a landscape; the tree becoming its own forest. If you’re deciding on what lens to work with, think about which of these applications it would be suited for, and whether it would be applicable to more than one. I’ve broken down in a bit more detail on Emulsive about the way I work on my documentary stories, which include who, what, when, where, why contained within a story arc with a beginning, middle, and end.

The three lenses I gravitate towards are all classic focal lengths, I think in part because the above three forms of wide/mid/close within my usual range fit so well into their field of view, although as I said at the start it isn’t always obvious which will be which in context. They are mainstream to the point some would say they are a generic choice; 35, 50, and 90mm, but I think they are generic because they are so versatile, their reputation coming from practicality and functionality rather than gimmick and trends. My iterations of these focal lengths for rangefinder are small enough that they have roughy the same surface area as my Nikon 85mm 1.8, which is by no means a large lens itself.

An SLR user may buy into an “ecosystem” of lenses, with the classic photojournalist everyday carry consisting of a 24-70, 70-200, and maybe a 50mm prime. If you’re working with a rangefinder and want to cover the same range you’d be needing maybe five primes and a visoflex – but the point of the rangefinder system is not to be a catch all. A variable focal length lens does some of the work for you, encouraging a frame that’s obvious from where you may be standing. Primes mean that you do the work, the literal legwork in making the world fit into your frame, not the other way around.

Working with my three lenses I can work in all kinds of conditions, peaceful to violent, landscape, cityscape, seascape, urban, rural, everything in between. I can compose using layers and complexity, or isolate to one subject at a time. They are versatile within my set of needs, and will not offer me those special case results of macro or super-telephoto. By really concentrating on spending time on such limited gear I can cultivate a deep literacy without distraction.

With enough practice and experimentation you may find that three lenses isn’t necessary, that you can actually achieve what you want with only one. I know some photographers who only use the Nikon 55mm f/2.8 as a “do-it-all” lens, as it covers everything they need it to from very close up macros, to portraits, to general view scenes. They don’t need anything longer for telephoto, and their style for closer scenes doesn’t need the expansive field of view of something wider, only the proximity the macro provides.

Many rangefinder photographer stick with only one lens and can go their whole practice without feeling the need to switch things up. I know that when you look at the work of Benjamin Gordon you are seeing a 50mm frame, as aside from when I briefly lent him a 21mm Zeiss lens (and possibly other slight exceptions similar to this) I believe 50mm is all he’s ever used. Just take a look at his portraits, sky-scapes, moments of action and intimacy caught in all kinds of situations to see the heights of what a one lens approach to photography can offer.

For documentary photography, where a story and narrative involving people is centred, focal length does not need to influence the image. A situation may demand a certain approach, but it will rarely be one of those special use lenses outside of the mainstream classics. They are the classics for a reason. Even though I carry three lenses when I know I’ll possibly be in a situation that requires them I find thatI’ll usually settle into a combination of 35/50 or 35/90, or sometimes even 50/90. I can feel out a situation and broadly know the result I’ll be after in advance, but this comes from many failures beforehand.

When photographing a project in D.C. I barely used my 50mm when outdoors, instead switching between 35/90. Then when I was indoors at the Shadow Representative office I worked almost exclusively with the 50. Mostly I worked at 90mm, including the cover image which maintains depth despite being one of the more refined and minimal images from the project.

In crowds such as at protests where I’ll want to switch between action and detailed images a 35/90 combo is more appropriate. As I touched on before, these are not hard and fast rules, and I can adjust as necessary or appropriate in the moment.

Working with three, two, or one lens is not for everyone. It may be that you do need the versatility of a 24-70, 70-200, teleconverter, mirror lens, super wide, macro and everything else, and shouldn’t attempt to do it all with just one. You can have the most focused of intentions but still need to rely on diverse gear. You don’t need to justify that decision, as long as you don’t find it getting in the way. It’s the result that matters, and working towards that result effectively as a photographer, not a camera operator. It may be that you can do everything you need to with a 24mm and a 200mm. It could be that any combination you use for one project may be entirely irrelevant for the next.

While photographing my recent project Foundation Stone I used a combination of 35, 50, and 90mm lenses, but mainly stuck to a 35mm/90mm combination. I recently wrote about using a low speed film indoors in low light during the early morning while documenting this day. Please consider supporting this richly informative and intimate community documentary work! Where working with multiple lenses and bodies really comes into its own is to offer multiple perspectives within a short amount of time. When piecing together a story in multiple images I will often look to find a wider perspective on a situation, then follow up with something more personable, and then expand on that with a detail or contextual element. Of course this is still possible to achieve with only one lens, but it helps shape my mindset when making decisions and understanding where work as I make it will end up in the sequenced medium in which it will eventually exist.

Share this post:

Comments

PixelChristi on Storytelling with Three Lenses or Fewer – A Rangefinder Workflow – by Simon King

Comment posted: 15/12/2022

1/ Consistency of vision, or what some might call their “style”. Using a specific tool well across an entire project can be an important cohesive factor in how well things hangs together.

2/ Constraints beget creativity. By constraining yourself, you force yourself to find creative solutions, compositions etc. As you alluded, all art creation is a series of choices, by minimising some choices at the start of a project you experience less friction throughout. There’s no rabbit in the headlights moment, no choice paralysis. At least in my experience.

3/ A fundamentally more comprehensive understanding of the tools you /do/ use. By using a 50 exclusively, for example (my first choice most of the time), you’ll almost certainly be able to accurately “see” the final image more consistently.

I do have a wide variety of lenses; even a super telephoto for wildlife, because during the height of the pandemic, the appeal of essentially going fishing with a lens was irresistible. It’s supremely relaxing, to find a spot, set up the tripod and camera and simply sit, coffee at hand, waiting for things to happen.

For my own serious project work though, I generally choose one lens and stick to it throughout. That’ll either be a 50 equivalent, or an 80 equivalent. That way I keep my work consistent, flowing, and (in terms of my “photographic eye”) predictable.

John Fontana on Storytelling with Three Lenses or Fewer – A Rangefinder Workflow – by Simon King

Comment posted: 15/12/2022

Marco Andrés on Storytelling with Three Lenses or Fewer – A Rangefinder Workflow – by Simon King

Comment posted: 15/12/2022

« my freedom will be so much the greater and more meaningful the more narrowly I limit my field of action and the more I surround myself with obstacles. » Igor Stravinsky

The counterpoint is « The tyranny of choice » examined in « The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More » Chris Anderson. Presenting a limited selection of gourmet jams and chocolates made people more likely to purchase and more satisfied with their choices.

I use a similar approach: a folder, a tlr or a rangefinder with a 40mm, 50mm or 90mm. Frees me to concentrate on making the image.

Pierre Saget on Storytelling with Three Lenses or Fewer – A Rangefinder Workflow – by Simon King

Comment posted: 15/12/2022

David Hume on Storytelling with Three Lenses or Fewer – A Rangefinder Workflow – by Simon King

Comment posted: 16/12/2022

Comment posted: 16/12/2022

Ted Ayre on Storytelling with Three Lenses or Fewer – A Rangefinder Workflow – by Simon King

Comment posted: 16/12/2022

Comment posted: 16/12/2022

jason gold on Storytelling with Three Lenses or Fewer – A Rangefinder Workflow – by Simon King

Comment posted: 20/12/2022

Why 50mm? It's your best lens available, in terms of quality, sharpness and good lens speed. Only one 50mm is lousy quality. falls apart. Eos 50mm. Thankfully I don't use that system Any SLR with 50mm is more than adequate. Easy to afford.

A cool solution for me was compact cameras evolving into digital. I KNOW you all film heroes! I am not prepared to spend that money on simple snaps. Each his own.