Recently, I was very kindly given two 110 cameras by submin exponent and expert, Bob Janes, one being the very compact and immaculately designed Minox 110S, out of the top tier of this format’s offerings. Made for Minox from 1978 by Balda, who continued a similar design after Minox dropped it from their catalogue.

Appearance

Closed, the camera is very pocketable. Around the size of a small bar of chocolate or a cheroot case in all black with a few discreet graphics and scales, a bright red shutter release and flash cube and dedicated electronic connections. A couple of sliding patches give access to the film chamber and open the long clamshell doors covering the lens, meter and finder with the eyepiece and film window on the back. The clamshell slide doubles as the battery check when pressed sideways with a small LED alongside to register battery condition. There is a sliding focus adjustment and a small wheel and window that controls the aperture setting on the top. A bayonet type of connection on one end attaches a strap loop and a tripod socket is provided on the base. It weighs very little compared to some and is largely constructed from plastics, but of the best quality and finish.

Operation

The most pressing need with this largely automatic camera is to provide the power it needs to work at almost any setting. Unfortunately it originally operated using mercury cells, nowadays banned, so alternative batteries must be found.

There are several options but I decided on size 675 hearing aid batteries, the largest now available, outputting 1.4v, and a close match to the 1.35v cells required. Adding an o-ring matches the diameter of the original cell. Two batteries are needed and appear to be used in series so their 2.8v is very close to the 2.7v the mercury cells would have delivered. A test also indicated that they last for 5 days or more so it would be reliable to use one set per session at minimal cost. A 6-pack cost me NZ$12 = £2 or US $1.20 a pair, cheap enough to replace them every outing unless you are shooting a lot when the adapters to take modern cells that are available would be a better choice.

The o-rings help locate them in the camera – being in the door they can easily fall out if not a snug fit under the sliding retainer. The slight downside is that they are located in the film chamber so changing them mid-film would cost a frame or three unless there is a changing bag handy.

Loading film is simplicity itself, just drop in the cartridge as usual. Wind off the leader, double stroke per frame, then check the battery which is done with the doors closed and the shutter cocked. There is the usual film speed sensor which also seems to be connected to a cartridge sensing tab that is held down when the film is inserted and may be connected with the shutter operation.

Sliding the long release opens the doors covering the optics and meter and switches the camera on. The finder is generous and clear with an automatically parallax adjusted suspended frame, aperture setting and meter indications with a rangefinder patch in the centre. Focus is from ∞ to 2ft/0.6m.

Initial pressure on the shutter release may bring up a red or yellow arrow either side of the aperture value shown in the centre. The aperture must be adjusted with the small wheel provided in the direction of the arrow until the arrow disappears when the shutter speed is within hand-held range for the aperture set. If either arrow remains lit, the shutter speed range is exceeded. This takes no time at all to do in practice. So aperture priority auto, the arrows only warning of under- or over-exposure. Extra support or flash is needed if light levels are too low with the danger of camera shake. Shutter speeds are electronically controlled in the range 4sec to 1/1000sec. Even though the electronic shutter clicks, mechanical activation, it doesn’t open without power to set the speed, hence the importance of the battery.

Turning to the flash setting sets the shutter to a mechanically 1/40sec, with or without a cube or flashgun connected. The aperture alters in line with the focussed distance for the flash units out to 25’ for cubes. Close distance will mean a small aperture which opens up as distance increases. It gives an extremely limited range of manual exposure and is possible but hardly practical.

The rangefinder focuses in the usual way using the slider on the top of the body. Not working on this example, the depth of field is indicated by the red lines either side of the distance index which move in or out with changes on focus, the gap created indicating the range.

Handling generally is very comfortable with good ergonomics.

Results

The 25mm, 4-element, f2.8-f16 lens receives excellent reviews and this example bears that out, helped a great deal by the rangefinder focussing. Many 110 models rely on depth of field to handle focus, but, even with such a short focal length, there is no substitute for accurate focus if optimum sharpness is to be achieved.

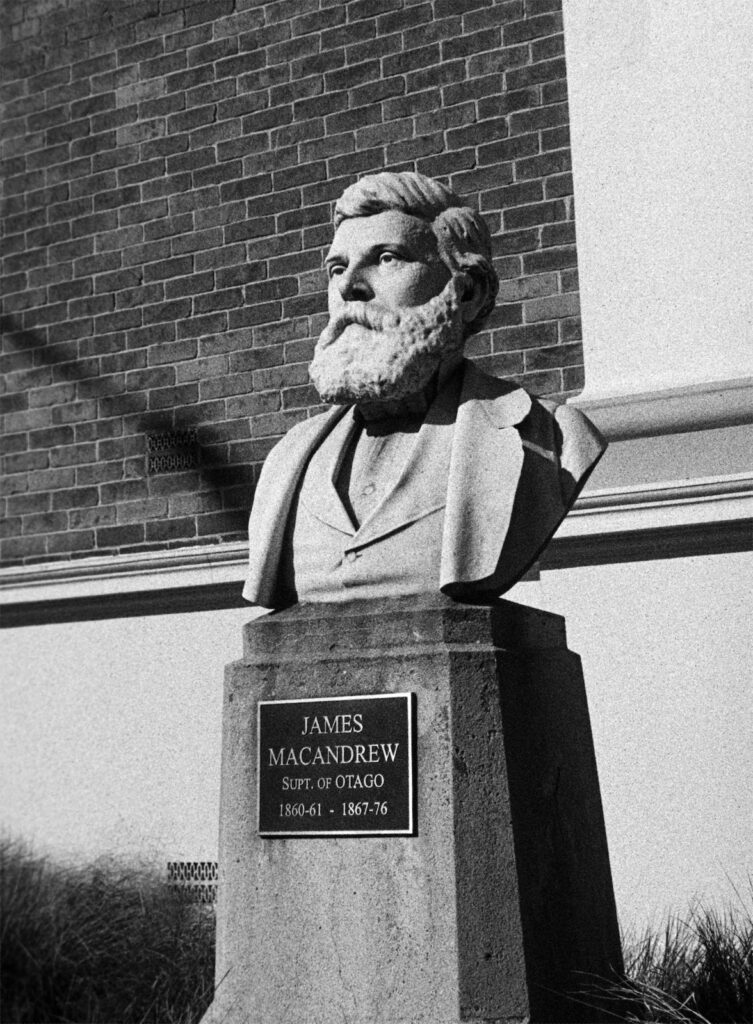

The images from this cracking lens show excellent sharpness, testament also to the accuracy of the rangefinder. The lens is very resistant to flare and the meter produces accurate exposures in a wide range of lighting conditions. Lomography’s Orca monochrome film, though not the finest grain film has good contrast and acutance, grain only being very obvious in plain, mid-tone areas. I has something about it that reminds me of Tri-X of many years ago when ‘slightly gritty’ was fashionable.

Comment

The manufacturers who produced 110 cameras used their own interpretation of how their camera functioned. For simplicity, the basic 110 system uses a single perforation in the film which controls frame spacing with a fixed focus lens and single shutter speed being the norm with a couple of apertures available. The framing control uses a feeler which springs up into the perforation as the film is wound over it and stops the transport mechanism to match the pre-printed image frames on the film and cocking the shutter at the same time.

Manufacturers of more sophisticated models, Minox included, combined the framing control with a cartridge sensor or a shutter release limiter or both in various, often sophisticated ways, blocking release unless a cartridge is present and/or the feeler has risen into the perforation. The method used here combines these two functions making fooling it near impossible. For me anyway.

In addition to linking the cartridge sensor with the speed sensor in some way, the battery arrangement and electronic shutter adds to the complications. This means the camera will only work with the film door closed, and a cartridge and batteries loaded. And so commercial film has to be the order of the day and Lomography’s Orca has been my choice here.

The higher spec 110 cameras produced around this time were soon replaced by simpler loading systems and motor drives for compact, pocketable 35mm cameras. The small size and easy film loading had been the main advantages of 110 and then the disc system, the final throw for Kodak. 35mm was too established and gave better quality from the new, almost completely automatic models. Digital, too, was not far off and the mobile phone into the bargain. The last quarter of the 20th century really was a period of rapid developments.

Share this post:

Comments

Bob Janes on Minox 110S review

Comment posted: 17/10/2024

Comment posted: 17/10/2024

Gary Smith on Minox 110S review

Comment posted: 18/10/2024

Comment posted: 18/10/2024

Rhys Thomas on Minox 110S review

Comment posted: 28/10/2024

Comment posted: 28/10/2024