As I write this, a heavy shower has just passed and the sun is beaming down once again. Photons are showering the solar array on my roof and switching our power supply back to free electricity. Solar power has been a long time in the making. The photovoltaic effect was first observed in 1839 by Alexandre Edmond Becquerel at the astonishing young age of 19. From a family of scientists, and also with an interest in photography, he coated platinum electrodes immersed in an electrolyte with silver chloride or silver bromide. When light was shone on the electrodes, voltage and current was produced. The first practical solar cell didn’t appear for another 44 years when the American Charles Fritts utilised the semiconducting properties of the element selenium. One year after his invention, a selenium cell solar array appeared on a New York rooftop in 1884.

Fritts coated selenium with a very thin layer of gold. The system was very inefficient and expensive for large scale use, but the selenium cell eventually found its niche in measuring light for the calculation of exposure times in photography; the light meter.

The Electrophot DH made by the J. Thos Rhamstine company of Detroit was the first commercial selenium cell exposure meter. It was heavy, expensive and curiously required battery power. Rhamstine was trumped a year later in 1932 when the Chicago based Westphalen company produced their photoelectrometer; no battery required.

It wasn’t long before camera manufacturers realised the advantage and convenience of having a light meter attached to the camera; either as a clip-on or built into the camera design. The first high end camera to offer an integrated selenium meter was the Contax III of 1936, but the ‘golden age’ of the selenium cell metered camera was roughly between the middle of the 1950’s to the middle of the 1960’s, although there are notable cameras outside this period. Olympus were offering the XA4 of 1982 with a selenium cell around the lens, little changed from that of the Pen EE half frame camera some 20 years earlier. Likewise, the Zenit EM SLR with uncoupled selenium cell meter was produced until 1984.

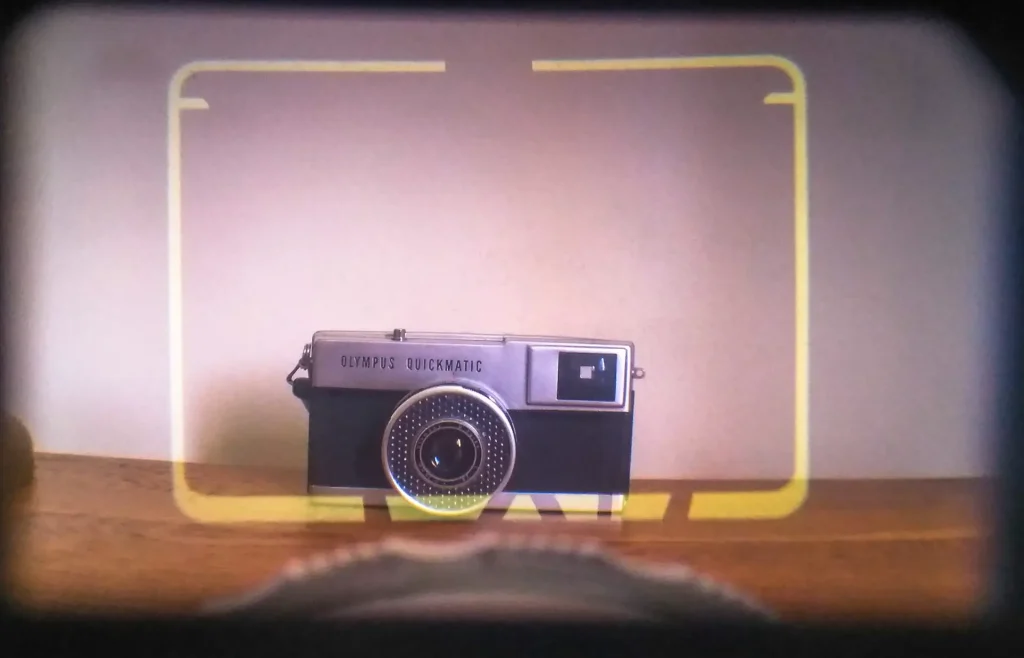

Going back a few decades, for late 50’s SLR’s clip-on meters were the approach. Cameras such as the Minolta SR2 and Yashica Pentamatic had a bracket fixed to the camera body for attaching the meter – handy and ungainly in equal measure. Meters integrated into the camera body were more convenient and gave the cameras a distinctive look; an area of the camera taken over by what looked a bit like inflexible bubble wrap. For SLRs, the front of the pentaprism housing was usually given over to the meter. For rangefinders and viewfinder cameras it was either a rectangular panel on the front of the body or a doughnut shaped arrangement around the front lens element.

For SLRs, the more convenient Cds meter was already on the horizon. The Cadmium Sulphide meter required a vastly smaller light-collecting area and opened up the possibility of measuring light from within the camera itself after it had travelled through the lens.

The selenium cell may be old technology, but I think it has had a bit of a bad press in some quarters; seen as unreliable and likely to ‘wear out’. From my experience, I don’t think either is true. There are an abundance of cheap, fully working coupled and uncoupled selenium cell cameras out there on auction sites and car boot sales, waiting to be picked up and used again. I have a few of them, all with meters in accurate, good working order.

As well as the convenience of not having to carry a separate meter, the selenium cell meter’s major contribution to the development of 35mm photography was exposure automation, and that’s where my interest is. The use of a selenium meter to help calculate shutter speeds, apertures or both is convenient, quick and ideal for novices.

Olympus Trip 35

I suppose the first camera that springs to mind is the popular and ubiquitous Olympus Trip 35 with fully automatic exposure, manufactured for an incredible 17 years. There are tons of them out there being revived and used; and going for quite silly sums of money when you consider 10 million were made. There must be a lot more out there at the back of wardrobes and in lofts.

The Trip is light, small and can produce quality results. The selenium meter does all the work; selecting one of two shutter speeds (either 1/40th sec or 1/200th sec) and an aperture from f/2.8 to f/22. Before lockdown scuppered things, I had started a project called cathedral views, all images of Durham cathedral from various parts of the city using a Trip. The camera hasn’t put a foot wrong on the first roll of film.

You don’t have to pay over the odds though for a selenium meter equipped camera with a degree of automation. There are earlier incarnations of exposure automation out there that can be had for little money. Some models are a bit ropey with regards to build quality, while others are pretty high end cameras.

Durst Automatica: the stylish Italian

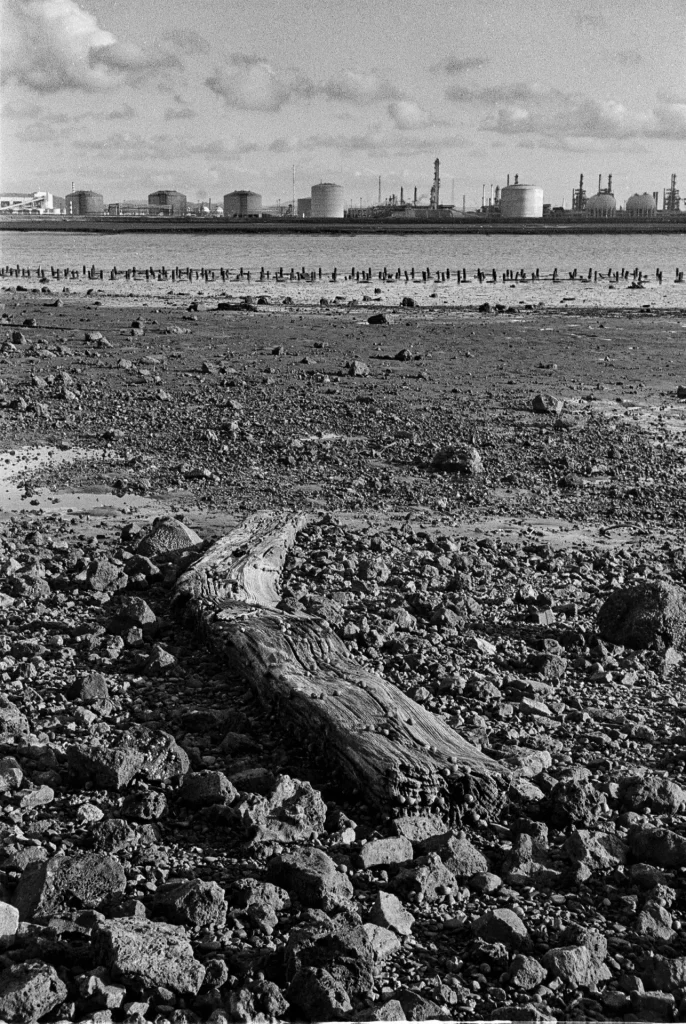

The very first of the automatic cameras was the aptly named Durst Automatica of 1956 (possibly). This is a well made and beautiful viewfinder camera which has a limited form of aperture priority automatic exposure and a unique pneumatic shutter release. Setting the film speed using the innermost dial on the lens is directly linked to aperture selection. There’s only one aperture for any given film speed. The top ISO setting is 400 and the maximum lens aperture is f/2.8, but never the twain shall meet in an automatic exposure! The selenium meter governs the shutter speed in a range from 1/4 second to 1/300 second, which can be read from a needle indicator on the top of the camera. For extra versatility, a switch on the front of the camera disables automatic exposure and you are free to select any aperture and shutter speed combination. I took the Automatica to photograph my local estuary and it produced well exposed negatives.

Agfa Optima

The very first Agfa Optima of 1959 is another pioneer worth seeking out. I didn’t have high hopes for this chunky viewfinder camera, but it set me right with some lovely colour images. It even survived me dropping it. I watched it bounce three times on tarmac before I retrieved it from under a parked car.

The Optima’s claim to immortality is that it was the first camera with programmed exposure. A left hand lever on the front of the camera appears to be the shutter release. It isn’t. It actuates the light meter. The lens is a somewhat slow f/3.9 39mm Color-Apotar. Maximum ISO is 200. The shutter speed range is 1/30th-1/250th second. Based on the light measurement of the selenium meter, and the set ISO, the camera works out if you have enough light for a decent exposure. If you have, it displays a green light in the viewfinder. If not, it displays a red light. It is beautifully simple and proved effective; although you are limited to shooting in good light.

Kodak Retinette IIA

Another German model from 1959 is the Kodak Retinette IIA. Kodak made a confusing array of very similar rigid body Retinettes. This one wasn’t in production long.

The Retinette IIA didn’t quite have full automation, but it was still a very simple camera to use. You turn a ring on the lens to center a needle visible in the viewfinder. You are actually changing the lens aperture, leaving the camera to work out the appropriate shutter speed. One cool feature of this camera is the depth of field indicator. Because the camera does not indicate the shooting aperture, Kodak devised this alternative way of indicating depth of field, utilising two red markers that converge or diverge on a scale on the lens barrel as you turn the aperture ring. One other great feature of this camera is the ability to set ISO to an amazing 3200, enabling the use of fast, modern films. Coupled with an f/2.8 lens this camera has a surprising range.

Olympus again

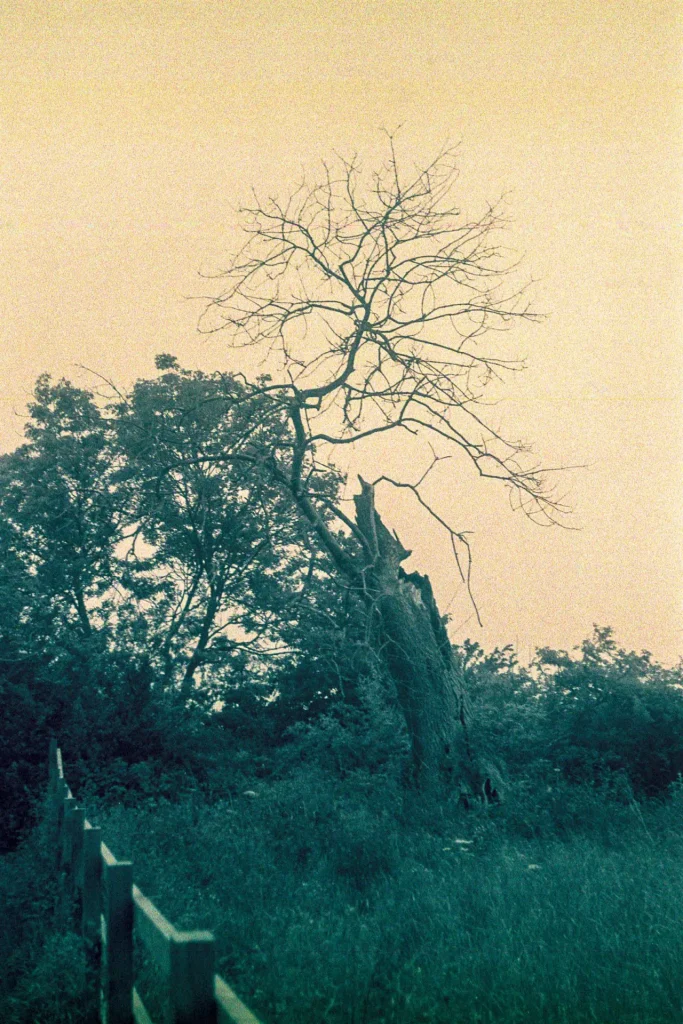

Leaving Germany now for Japan, it was Olympus who were the first of the Japanese makers to exploit exposure automation with the selenium meter equipped rangefinder called the Auto Eye of 1960. The Auto Eye provided shutter priority automatic exposure by means of ISO and shutter speed selectors both accessible by rings on the lens barrel. A unique “pre-VU” lever on the front of the camera body allowed you to see the lens aperture the camera had chosen via an indicator at the bottom of the viewfinder. The Auto Eye offered a shutter speed range of 1 second to 1/500th second and a maximum ISO of 800. Not bad! Olympus selenium cell technology found its way into their PEN half frame cameras, beginning with the PEN EE of 1961. This camera had fully automatic exposure and fixed focusing. The first version show here had a single shutter speed, a range of apertures chosen by the camera, and was limited to an ISO of 200. A genuinely pocketable model, I regard it as the first true point and shoot camera. For me, this camera gives poor results with colour film yet surprisingly good results with black and white. I blame the photographer for this discrepancy!

The Kowa H – lottery in camera form

Last in this sunshine bathed tour of my selenium cell equipped cameras is a fixed lens reflex model. I can’t recommend the Kowa H of 1963, but go ahead and try one if you wish. I am onto my third and still not quite 100 percent copy of this leaf shuttered SLR. It is a notable camera, being the first Japanese SLR to be equipped with a coupled selenium cell. It has a kind of crappy charm because the meter is accurate, it has an excellent finder, useful exposure information on the top plate, but poor build quality perfectly illustrated by the trigger style film advance underneath the body that only seems to cock the shutter every fourth time you operate it; unless you press down firmly on the fulcrum. A rough feeling metal thumbwheel on the rear of the camera changes the ISO between 25 and 400. The change is indicated in the exposure meter window. With the horrible cheap feeling lens aperture ring set to the red A, a needle in the exposure meter window indicates a fixed set of aperture and shutter speeds it has chosen. There are only four sets of options. |t is possible though to get good quality images out of the Kowa H, if you are lucky. The selenium meter is not the problem here, and I believe it rarely is with any of selenium meter equipped cameras.

Of the cameras I have bought, I have only encountered one with a ‘dead’ meter, and that is curiously the only one that came without a case. I believe corrosion caused by heat and condensation resulting in electrical resistance is the chief culprit for failed meters. The solution, with any form of equipment, is care and maintenance.

If you elect to leave batteries in your Cds metered Yashica Electro and stuff it in your drawer and forget about it, sooner or later they will leak and turn your battery chamber into green crud. Leave your lovely solar powered Automatica out in daylight with the meter forever engaged, and physics will do its thing – condensation and compromised circuits. If you want to preserve anything, then best keep it in a cool (not cold) dark and dry environment – vintage cars, the deeds to your house, cheese and wine, your collection of Top Trumps from the 1970’s. Please note though, this approach does not work with living things or marriages.

I’m not advocating anyone makes a selenium metered camera their forever number one shooter, or loads a roll of expensive transparency film in one; but for print film and experimentation I find them fun and fascinating. Some are capable of quality results.

Of course, entropy will get us all in the end, but in the case of selenium metered cameras you can push that fateful day further into the future with basic care and thoughtfulness.

Share this post:

Comments

paul brant on Always the Sun – In Admiration of the Selenium Cell Compact Camera – By Chris Pattison

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

Good to see results from the more accessible end on the market too .

Nice pics

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

Chuck - Detroit, MI - USA on Always the Sun – In Admiration of the Selenium Cell Compact Camera – By Chris Pattison

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

Mike B on Always the Sun – In Admiration of the Selenium Cell Compact Camera – By Chris Pattison

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

Scott Gitlin on Always the Sun – In Admiration of the Selenium Cell Compact Camera – By Chris Pattison

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

Harry Machold on Always the Sun – In Admiration of the Selenium Cell Compact Camera – By Chris Pattison

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

I enjoy a lot your British humor...

I will take your advice well into my next marriage...

Please, keep going here and elsewhere..

Best

Harry Machold

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

adventure! on Always the Sun – In Admiration of the Selenium Cell Compact Camera – By Chris Pattison

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

One correction: The one Olympus XA series camera with the selenium cell is the XA-1, not the 4. The XA-4 was the one with the wide 28 mm lens.

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

Rock on Always the Sun – In Admiration of the Selenium Cell Compact Camera – By Chris Pattison

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

Oscar Durán on Always the Sun – In Admiration of the Selenium Cell Compact Camera – By Chris Pattison

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

Gracias por publicar!

Oscar.

Comment posted: 17/08/2020

Kurt Ingham on Always the Sun – In Admiration of the Selenium Cell Compact Camera – By Chris Pattison

Comment posted: 21/08/2020

. It should be noted that a number of very interesting cameras have auto exposure linked to selenium meters that no longer function.And no manual override Using the 'flash' settings may work, but not really very well

I'd say more than half the selenium cells I encounter have 'given up the ghost'

Comment posted: 21/08/2020

Khürt Louis Williams on Always the Sun – In Admiration of the Selenium Cell Compact Camera – By Chris Pattison

Comment posted: 21/08/2020

Comment posted: 21/08/2020