I’d like to report an interesting (well, I thought so anyway) discussion that took place at my village camera club the other day. The topic was “How to Achieve a Gigapixel Image”. I’ve changed the participants’ names.

Dick: What’s the problem? Stitch 25 40mpxl images together from my Sony A7r3. Job done!

Socrates: You’re addressing the question of data collection which indeed is part of the process. But to create an image that is more than an invisible collection of data we also need to think about image presentation. Let’s discuss collection first, and suppose you are photographing a static subject – does your method work?

Spanner: I don’t think it does – is focus perfect? Are all parts of the scene equally in focus?

Maximus: I shoot f/32, sometimes as much as f/64, to get everything really sharp and in focus.

Socrates: OK, you’ve touched on several issues here.

Let’s start with focus accuracy. Digital AF cameras can achieve good focus quickly, sometimes better than manual focussing, but often not perfect – stepper motors may miss focus, continuous motors will not necessarily stop accurately. Manual focus on rangefinders and large format cameras is unlikely to be perfect in most situations – miss-calibration of mechanical or optical systems, insufficient magnification, eyesight problems.

For film cameras film flatness can be an issue even on 35mm cameras; on LF cameras the film slots have a wider aperture than the thickness of the film so it’s not clear where precisely the film is; film can sag unless a vacuum suction system is in place.

And f-stop is a big issue. Even assuming you have an optically perfect lens the laws of physics – specifically diffraction around the aperture blades – determines the minimum size on the focal plane that a point source creates. For example [reference 1 below] at f32 this corresponds to about a 20 micron pixel, f8 is about 5 micron and f4 is 2.5 micron. Compare this to Dick’s pixel size of 4.5 micron on his Sony and you can see that to get maximum use of the sensor you need to shoot at wider than f8, which limits depth of field.

Maximus: But shooting 8×10 I have much more film area to play with, even at 20 micron size that gives me potentially over 10gpxl [2].

Spanner: Are pixels relevant to film, aren’t we measuring things in the wrong way?

Dick: Yeah, this is nonsense! Film can’t resolve like digital sensors can!

Socrates: Spanner is right, film resolution is quoted (if it’s quoted at all which is rare) in terms of lppm (line pairs per mm) at a contrast range of 10 stops. The resolution of film depends on the characteristics of the particular film – grain size, grain shape, emulsion thickness are factors that spring to mind. It’s sometimes said that traditional 35mm film is like a 10-20mpxl camera, but other emulsions – tabular grain films, ultra-fine grain films or colour films (where the three emulsion layers improve resolution over a single layer) – can offer much higher resolution. For example Adox [3] quote 850mpxl equivalent for 35mm CMS 20, and about 250mpxl for HR-50 – corresponding to over 2gpxl and approaching 1gpxl on MF. We must also bear in mind what Spanner alluded to – converting lppm to pixels is only an approximate equivalence.

Maximus: I remember photographing on a windy day with a light wooden 4×5 and the negatives were blurry, but on a perfectly still day a 1 second exposure was brilliantly sharp. Surely a blurry negative is like a far lower pixel count, and the same applies to out of focus areas.

Socrates: Yes we haven’t covered precisely what we mean by a gigapixel image. Nor have we thought about all the factors related to data collection even for digital cameras. For film, development methods and chemicals are yet more factors which can influence the amount of image data.

Now let’s start to think about how we can view the data – image presentation.

Dick: Press the print button and send to a large format printer!

Spanner: That means scanning film for film capture – I bet that’s problematic.

Socrates: For film users Dick’s solution indeed presents a problem – I’ve heard it said that even professional drum scanners have a practical limit of 3000dpi which would limit 35mm to 12.5mpxl and 4×5 to 180mpxl. For analogue capture we have other options – projection and enlarging. Each brings a repeated set of issues similar to the ones we discussed for capture, for example we need to think about projector/enlarger f-stop to get maximum detail. Bear in mind an 8×10 print – like an 8×10 negative – has the potential for several gigapixel of image data. It is often said that only 300-500dpi resolution is all that is needed for a print but tests have shown that viewers can discern much higher print quality that this.

There are other aspects of presentation which Dick glossed (or matted?) over when he suggested press the print button. For example when we enlarge there is a choice of paper – material, texture/finish, tone for B&W prints – let alone choice of developer and toning options.

A digital print compared to a wet-process print is a bit like comparing oil painting to watercolour – they are different, some prefer one, some the other – and what is appropriate to the task in hand and the photographer’s intention is always a good starting point.

Vincent: Now we are getting to something that matters! What are you trying to do with photography – simply record or produce something artistic?

Simon: I like vibrant colours, my friend prefers pastel, some even B&W.

Julia: And pixels or lppm have little to do with a good image – look at some of the images of the Normandy landings, out of focus and blurry, or the famous racing car by Lartigue with oval wheels tilted forward and spectators leaning backwards. Art is art and doesn’t need pixels or scientific accuracy! It’s way beyond data collection and presentation – there’s so much more that you can get up to using photography to produce something artistic.

Socrates: I think that has got to the point. If you are a research scientist photographing deep space from a satellite, or a police camera operator, or a commercial photographer, issues like detail and accuracy as well as efficiency come to the fore. If you are trying to produce art you may want to use a Holga and pour Coke onto the film before developing it, then scratch the negative with steel wool. And there’s a whole range of intentions between these extremes with their own solutions.

Here the discussions ended – at least for now.

Please don’t sweat too much over the numbers, and contribute your thoughts!

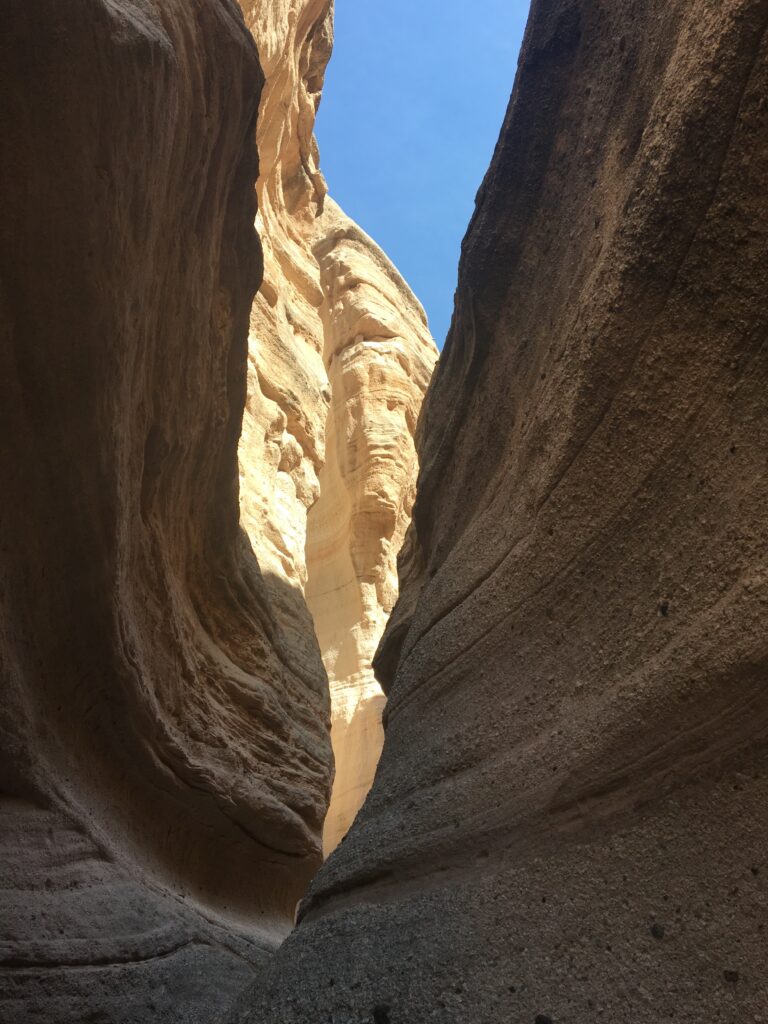

The featured image: The large image is a 2mx1m digital print from a 4×5 negative on Velvia 50, the small image is an 8×10 print shown for scale. Looking at the large print with a 10x magnifying glass it is hard to find any sign of grain – partly because of the type of image itself. From the print – which was made from a scan – I estimated the negative to be around 200mpxl equivalent. I don’t have a powerful enough microscope and scale to measure the negative itself.

Note on Resolution and f-stop:

Diffraction limits the minimum size of the spot that a properly focused lens can produce – for a given focal length this size decreases as the aperture increases. The size of the spot on the film plane is larger as focal length increases, so it turns out that whatever format you are using, it is the f-ratio that drives the size of the smallest spot on the film; smaller f-stop numbers lead to a smaller image spot on the film. The spot size (“the Airy disc”) is measured to the mid-point of the (first) dark ring surrounding the central bright spot and corresponds to the minimum distance where two points can be seen as separated on the film. For example at f8 the Airy disc diameter is approximately 10micron and corresponds to 100lppmm resolution or 5micron pixel size.

References:

[1] Edmund Optics: The Airy Disk and Diffraction Limit

[2] compare Jeffrey Luhn: (“4×5 Reborn ….” on 35mmc) mentions “Color 4×5 sheet film has at least 900 MP of ‘image data’”

[3] Adox: https://www.adox.de/Photo/films/

Share this post:

Comments

Jalan on The Gigapixel Image

Comment posted: 17/11/2024

Martin on The Gigapixel Image

Comment posted: 17/11/2024

A video from his playlist on Youtube (German but subtitles available) at around halfway through the video is a detailed summary

https://youtu.be/J8wuNAo-GwE?si=OLso2dXP1ahXkEK7

if links are not allowed here - sorry, it's @derschrei on YouTube

So everyone can find their niche. Very much like Bill Brandt said: Photography is not a sport, it has no rules. Everything must be dared and tried.

Loris Viotto on The Gigapixel Image

Comment posted: 17/11/2024

L'Arte visiva non vá a pixel, vá a "impatto" !!!

ciao a Tutti , e avanti così !!

Jeffery Luhn on The Gigapixel Image

Comment posted: 19/11/2024

Jeffery