The camera is a memory machine. And a legacy one. Photography is all about recording memories (or creating them) and building, whether you like it or not, a legacy. They, the memories and the legacy, slowly mature to become something bigger and more important over time. They become part of history; they create a historical record. Not always interesting or important, but there all the same. Not always visible or accessible, but there somewhere.

As an aside though, for us as individuals though, that historical record is only going to exist via our physical output. I believe it’s fanciful to think that our nearest and dearest, our descendants, will have any desire, let alone the capability, to access our digital/online archives. I operate on the assumption that when I go, so does my online presence (when the renewals lapse); so does my Lightroom archive (far too labyrinthine for anyone to do anything with). My digital archive will be toast and I’m ok with that because I’m planning for it.

I of course don’t take photos to create a legacy but I sincerely hope that it will have one. That’s not vanity, it’s pragmatism. I hope that my descendants are interested, fascinated even, in the photographic record I’m creating.

Getting back to the subject of vernacular photography, the great thing is, you’re probably already taking photographs that might, or will have, a historical interest. When I look back at some of my images, I can see that for a whole range of reasons they might be of interest in the future.

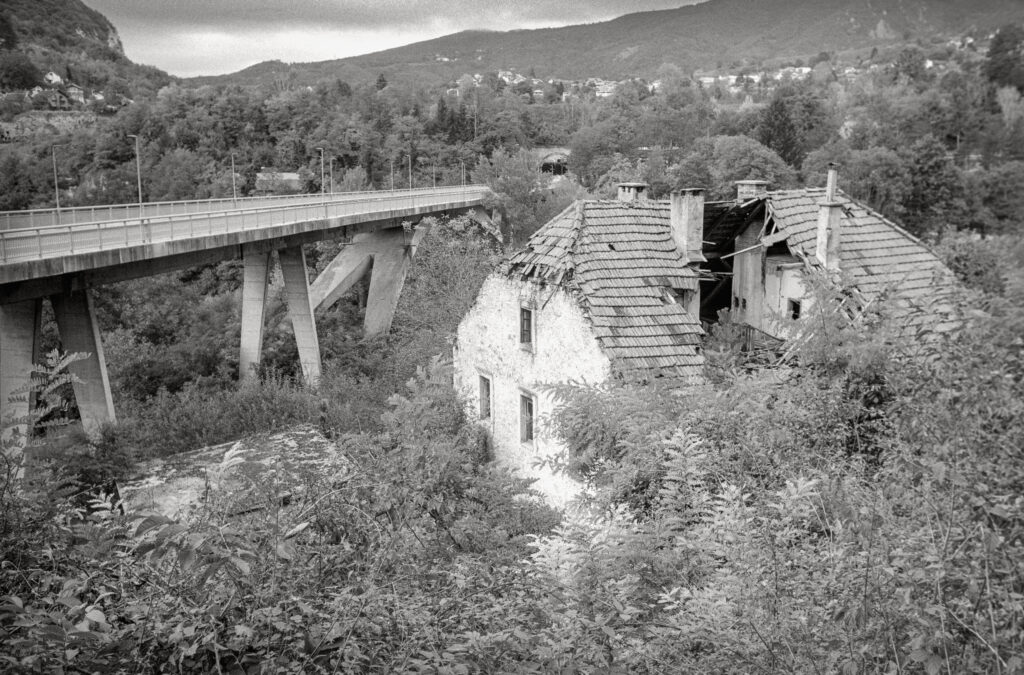

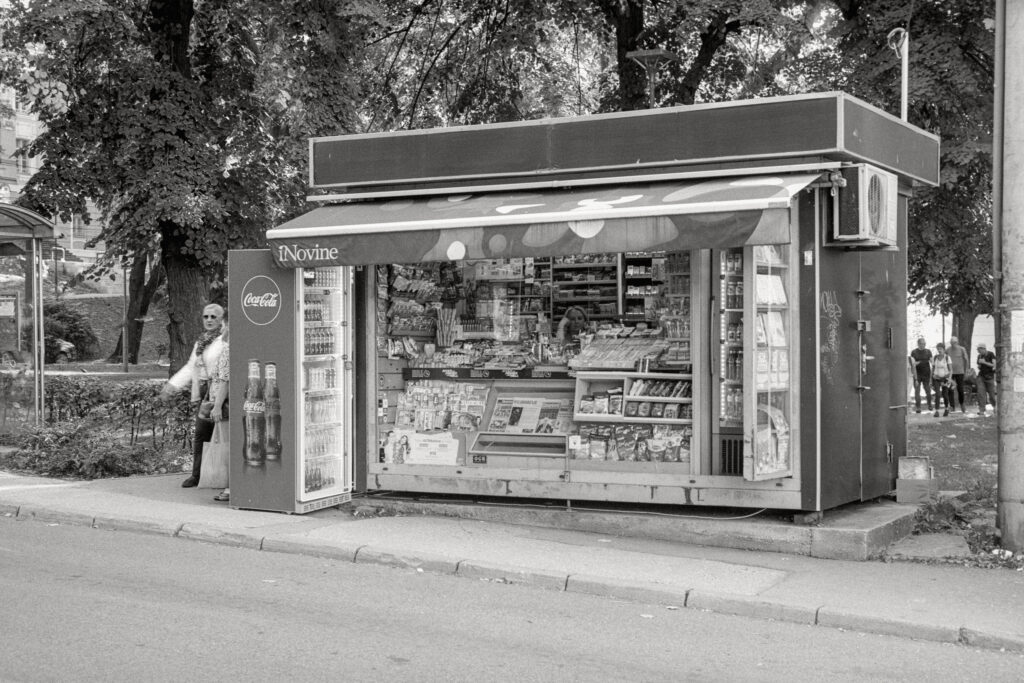

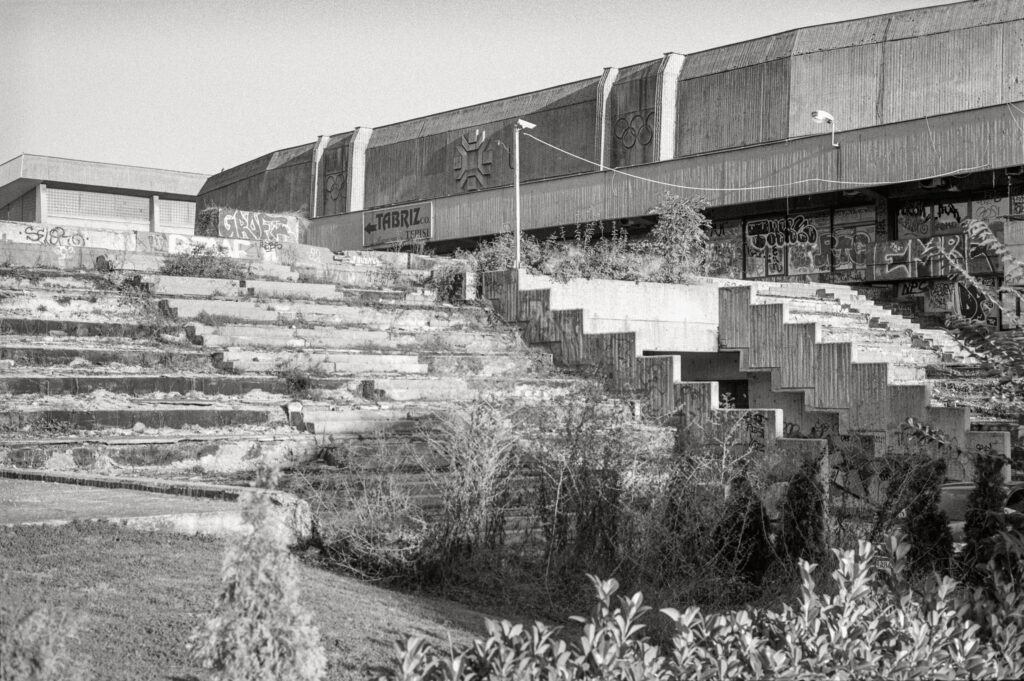

And it’s the most routine and mundane and seemingly unexciting things that will have the biggest impact. When you look you see. Have you noticed how frequently the shops in your local area change. They open, they go out of business, they change their displays, they change their branding above the door and so on. Petrol stations and similar utilitarian places close, get bulldozed, get replaced with new housing. Those trees near you that you think will always be there, they won’t. That waste-ground/field that will never be built on, it might. These tend to be the sorts of subjects that attract my eye; yours will be different but equally interesting. Eventually!

I didn’t really start this article intending it to be a memory manifesto, but I think what I’m gently alluding to is that whatever projects you’re engaged in, getting them into a printed form, even just one copy, could have lasting historical interest. How cool is that!

Walker Evans, Stephen Shore, Eugène Atget, Bernd and Hilla Becker, Vivian Maier… there’s a nearly endless list of photographers who’s published work helps us see and learn about what has disappeared from our urban landscapes.

There’s an interesting passage in William Boyd’s novel ‘Sweet Caress’ when the 1920s photographer protagonist says (and I paraphrase) that her decision to print is key to how she feels about an image and that in doing so, along with giving her prints titles, they live on in her mind “more easily and permanently” and are fixed in her “memory archive”. I believe this is also what I do with my favourite photographs; I bestow on them them printed permanence. Permanence and persistence through being a physical object.

I do stress again, however, that ‘legacy’ isn’t the reason I do what I do. Not by any stretch of my imagination. It’s a potential but very possible side benefit that I have no control over. Ultimately what I’m saying, and to summarise, is that no matter how ordinary you think your photographs are, and whatever your reasons or motivation for making them, collecting them into printed zines or mini photobooks or prints or whatever, will give them an unforeseeable life far into the future.

And here’s a parting thought: if you’re like me, you’ll always think that other photographers’ vernacular work is much more interesting than yours. Go figure that oxymoron.

I’m on Insta and I have a website too.

Share this post:

Comments

Geoff Chaplin on Spectacular Vernacular. Memory and Legacy.

Comment posted: 18/11/2024

Comment posted: 18/11/2024

Curtis Heikkinen on Spectacular Vernacular. Memory and Legacy.

Comment posted: 18/11/2024

Comment posted: 18/11/2024

Stefan Wilde on Spectacular Vernacular. Memory and Legacy.

Comment posted: 18/11/2024

Thanks for sharing!

Comment posted: 18/11/2024

Sasha Rose on Spectacular Vernacular. Memory and Legacy.

Comment posted: 19/11/2024

Comment posted: 19/11/2024

Peter Roberts on Spectacular Vernacular. Memory and Legacy.

Comment posted: 19/11/2024

For some years now I've got into the habit of producing an annual photobook with which to bore family and friends. Nothing special, and certainly not arty, just the sort of thing that the likes of Photobox enable you to create online at a reasonable cost. Presentation is everything and I try to replicate to look of a traditional album by giving the chosen images white borders and putting them on black pages with an annotation of title and place.

These books have the additional advantages of tracking the progress of my photographic ability, such as it is, and of being more readily accessible than boxes of prints.

Comment posted: 19/11/2024

Comment posted: 19/11/2024

Bill Brown on Spectacular Vernacular. Memory and Legacy.

Comment posted: 19/11/2024

Comment posted: 19/11/2024

Comment posted: 19/11/2024

Kodachromeguy on Spectacular Vernacular. Memory and Legacy.

Comment posted: 19/11/2024

Paul Quellin on Spectacular Vernacular. Memory and Legacy.

Comment posted: 21/11/2024

Comment posted: 21/11/2024

Bill Brown on Spectacular Vernacular. Memory and Legacy.

Comment posted: 24/12/2024