This is a review of the Minolta 9000, the first professional autofocus camera.

Back in the 60s and 70s the pro camera market was dominated by Nikon with their ‘bullet-proof’ F2 SLR camera. Canon made some inroads into this top-end professional market with their ‘F1’.

Minolta bodies were used by some pros as ‘workhorse’ cameras, in much the same way that Pentax Spotmatics were, but Minolta aspired to offer a top of the line camera that could compete with the Nikon F2 and Canon F1 cameras. Their first shot was the SR-mount Minolta X-1/XK/XM. It was an innovative camera. A great camera, but maybe a bit too innovative. Electronic shutter and automatic exposure were features that pros would adopt in the next generation of Nikon and Canon pro-level cameras. Newsrooms seemed reluctant to switch systems for features that were untried.

Into the late 1970s and 1980s, Minolta continued to innovate. The XD-7/XD-11 was the first camera with multiple exposure modes. The later X-700 had a program mode. Minolta got very strong in the high-end ‘enthusiast’ market.

Autofocus

In 1985 Minolta produced the first autofocus camera system

The lenses

On release there were 12 AF lenses available, ranging from 24 to 300 mm. This was filled out by another 14 lenses in the next two years, taking the range from 16 to 600 mm.

Lenses for the Minolta AF system were focused via a mechanical slot drive that keyed with a rotating blade on the camera mount. A mechanical linkage stops the aperture down to whatever the camera judges will give the proper exposure. Five electrical contacts allow the camera to read information from a chip in the lens, including focal length and maximum and minimum aperture. Later generations of cameras added another 3 contacts, supplying power to internal motors and getting information on focusing distance for flash exposure.

The cameras

The first camera to be released for the new mount was the ‘7000’.

This camera was known as the Maxxum 7000 in the Americas and as the a-7000 in Eastern markets. In Europe it was just called the 7000. I will just be refering to the ‘7000’ from here on, to cover all the regional variants. Note that Minolta adopted the ‘Dynax’ brand for European markets with their second generation ‘i’ cameras.

The 7000 was a high-end prosumer camera with lots of exposure modes, a built-in winder and reliable autofocus. It was a prime example of disruptive technology in a market area Minolta were already very strong in.

Later in 1985 Minolta released a second camera using the new mount. This was their shot at the professional market and is said to have been developed before the 7000. It was the first of three cameras targeted at professional photographers that Minolta would make for their new mount over the next 15 years.

Minolta 9000

The Minolta 9000 (Minolta Maxxum 9000 in the US and Minolta α-9000 in Japan) is a comprehensive and innovative camera. However it has some rather more ‘retro’ aspects.

Manual wind

This is an autofocus camera without a built-in autowinder. Instead it has a wind-on lever and a rewind crank. Although you could wind on if the batteries gave out, lack of power would mean that the shutter wouldn’t fire, so there was no huge benefit there. As pointed out by Mark Lewis in the comments, the manual winder did allow for relatively quiet winding.

It is notable that, even without a built-in winder, this is a chunky camera. Without a lens it weighs 708g, put a small prime on it, and it tips the scales at around 950g.

Bolt-ons

Minolta did offer an autowinder and a motordrive which screwed into the camera base-plate of the Minolta 9000. The autowinder did 2 fps while the motor-drive could manage 2, 3 or 5 fps. The motor-drive could also rewind the film. There were also options for interchangeable backs which expanded the options for data imprinting and added extra exposure modes. Another back allowed the use of bulk film in special 100 exposure cassettes.

The SB-90S still video back allowed digital capture. My initial excitement in discovering that the 9000 could have a claim to be the first ever digital SLR cooled after a bit of research. The SB-90S was huge, had a 4x crop factor, produced 640×480 NTSC resolution images and required for the mirror of the 9000 to be removed (so, not actually an SLR at that point).

Features

Even without the bolt-ons, the specifications of the Minolta 9000 are quite impressive:

- PASM exposure modes, including a program mode that took account of lens focal length and allowed the photographer to ‘shift’ the initial program values to ones that gave the same exposure.

- An electronic shutter with a range from 30 seconds to 1/4000, with a flash synch at 1/250

- DX film compatibility (with override)

- Interchangeable focus screens (a choice of 5)

- An AF/MF switch

- Exposure compensation (up to 4 stops either way)

- Exposure lock

- Choice of centre-weighted average, spot or highlight/shadow spot metering

- Full information viewfinder with a viewfinder blind and dioptre adjustment

- Double exposure switch

- Electronic remote release socket

- Depth of field preview switch

- Self-timer

- Jog-switches to adjust exposure settings on the front of the top-plate and the left side of the lens mount

- Powered from two conventional AA alkaline batteries

- Wind on lever(!)

Above you can see the opened back showing contacts for reading the DX code from the 135 cassette and those for communicating with the databack under the shutter. On each side of the viewfinder are the dioptre setting and lever for the shutter blind. Over on the right are the AE Lock button and button that allows you to cock the shutter without winding the film on.

The system already had an impressive range of lenses. Any competitor wanting to be on a level playing field would have to either produce their own dedicated AF mount, or produce versions of their lens range with AF compatibility. Minolta had a head start on the competition and they had a great product.

A stroll around the deck of the Minolta 9000

The LCD in the centre of the PASM selector is very prone to bleed. Also visible here are: Contacts for dedicated flashguns, the window to illuminate the prism LCD on the front of the hump and the shutter-release, self timer switch and on-off switch surrounding the wind-on lever hub.

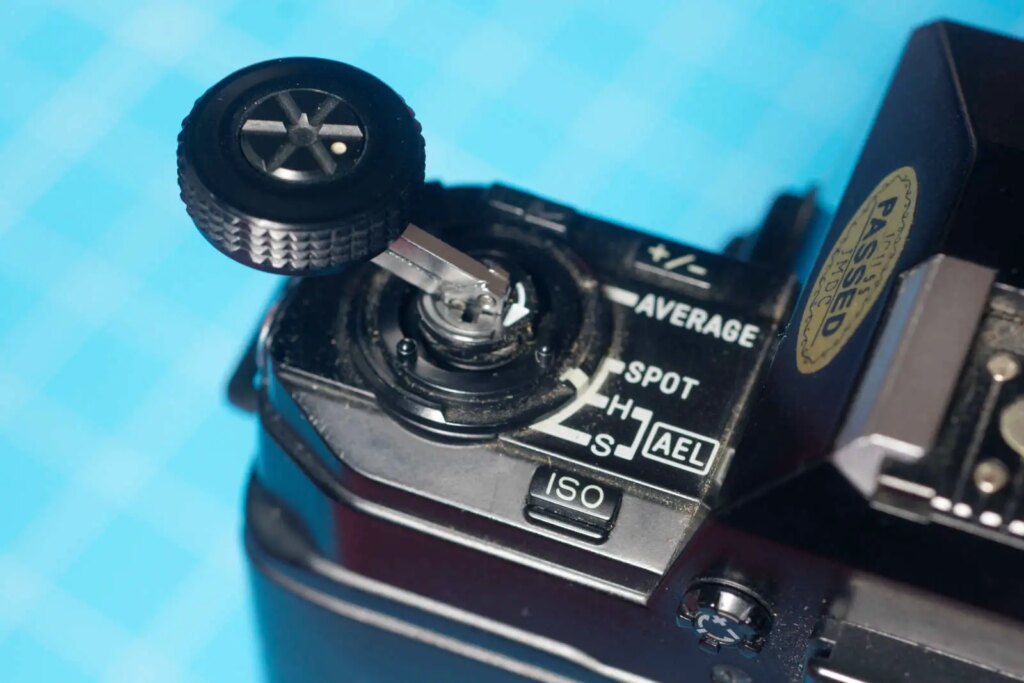

The Minolta 9000 has possibly the most over-engineered rewind crank ever conceived. It lifts and articulates on two rods for rewind. Pushing the switch in front of it to the right and pulling the dial up further pops the back. When lowered, the knurled dial on the rewind crank allows you to set the metering options and does not rotate as the film winds, but the inner section with the white dot on it does. The exposure compensation button is marked ‘+/-‘. The ISO button is for manual setting of film speed. Both are set by holding the button and using a jog switch.

The DoF preview switch has a little paddle that folds down for operation. The shutter release is touch sensitive to start up metering and autofocus.

The base of the Minolta 9000. Visible here are the lugs for hanging the camera on its end, motor-drive contacts, tripod bush, rewind button and opened battery compartment. Note the deterioration of the grip plastics.

In use

The Minolta 9000 is a lovely camera in use. Quite enchanting. The rewind crank is delightful to use, but what was wrong with a conventional crank? The depth of field preview switch (switch because it seems to work in a similar way to the one on the original SRT 101), is similarly eccentric. It almost gives the impression that someone was channelling a long-dead Zeiss engineer.

The jog switches work well and are an improvement on the rubberized buttons on the Minolta 7000.

The 9000 leaves you with a feeling of quality. You come to appreciate the sheer attention to detail and glory in the intricacies. The viewfinder is big and bright and shows pretty much all the information you could want with the camera to your eye. This is a precision instrument that is capable of just about anything, but as such it is quite complex.

The lenses

The lenses that Minolta released with the 7000/9000 have stood the test of time. There were cosmetic updates, but the 20, 24 and 50 primes that I’ve been using on the Minolta 9000 have only just gone out of production – and then only because Sony have finally discontinued the entire mount. The lenses were very good optically and primes made in 1985 are still in everyday use without showing their age.

Buyer beware

There are some things you should be aware of if you are considering trying to acquire a Minolta 9000.

- LED panels of this vintage are prone to bleed. I’ve never seen a 9000 without some bleed on the top-plate LCD. Often it is only cosmetic, but it can be bad enough to obscure the settings. The viewfinder LCD is also supposed to be susceptible, but I’ve not seen that.

- The plastics on the grip don’t age gracefully, they can become brittle and flakey.

- The 9000 has first generation Autofocus with a single horizontal ‘line’ type AF point. AF speed is slow. Glacial by modern standards. However, most current analogue film photographers are unlikely to feel held back by its limitations.

- Like most other autofocus Minolta cameras dating from before 1999 the 9000 cannot autofocus with lenses that have internal motors (SSM/SAM). The 500 Reflex is also not supported for autofocus with the first generation of AF cameras. The 9000 should work fine with other conventional screw drive AF lenses from Minolta or Sony.

- A notable weak spot are the magnets that are key to the lens stop-down. Without a working set of magnets the camera will appear to operate correctly, but the lens will not stop down to the correct aperture.

Capping

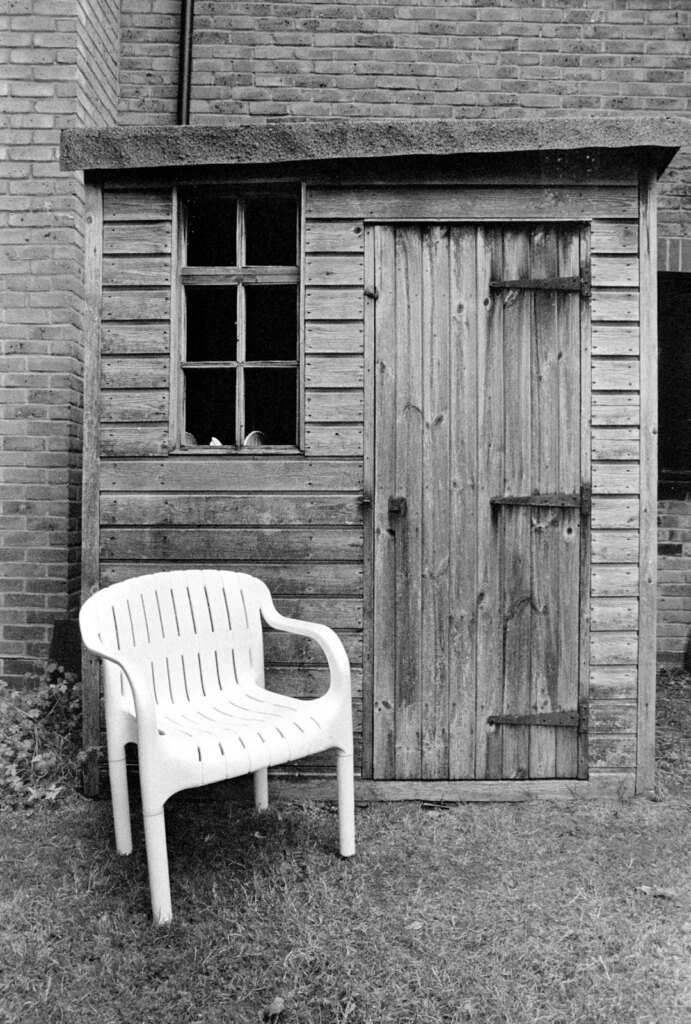

Another issue with this particular camera didn’t manifest itself until the first film was developed. There was some oil on the first curtains which seems to have caused come capping on a fair number of the shots.

It isn’t easy to check the shutter at different speeds on the Minolta 9000 with the back open. The camera sets itself to 1/4000 and minimum aperture for the first couple of shots on a roll, so you have to ‘fool’ the camera into thinking its back is closed to see the shutter open at other speeds. The shutter was cutting edge, I guess this is another example where cutting edge and cast iron reliable don’t necessarily go together.

Focusing screens

One of the 5 focusing screen options is the ’70 Type PM’. This features a split-image rangefinder and microprism. If this screen is in place, you can still use AF, but you get confirmation from the conventional rangefinder that focus is correct and it makes manual focusing (even with the original thin Minolta AF focus rings) a breeze.

There is a downside. These PM screens are rare. Even when someone thinks they are selling you a genuine PM screen they may be mistaken. When someone gets a PM screen they are quite likely to put it in a camera and put the standard ‘Type G’ screen from that camera in the box for the PM. Even if the box says PM, make sure there is a split image rangefinder at the centre of the screen and not an AF box.

On the plus side, this means that there is always the (remote) chance that the camera you buy will already have a PM screen fitted.

One work-around is to trim down the rear edge on a standard Pentax MX focusing screen – this should then fit in place.

Minolta 9000 Pictures

Conclusion

For Minolta the switch to a dedicated AF mount gained them considerable market share. Unlike Canon, they kept a line of SR-mount manual focus cameras going, thereby avoiding some of the ire that Canon attracted from certain FD mount users.

In the early days of AF, Minolta’s screw-drive powered by a motor in the camera body kept pace with Canon’s approach of having the motors in the lens. More advanced bodies with faster, torquier motors could give an old lens new ‘pep’. Later on, Canon benefited greatly from increasingly better and more reliable in-lens motors and an all-electronic mount. Minolta had to cater for changes to the mount to take advantage of stepper motors and such.

Nikon stuck with their F mount, adapting it for body mounted motors and later making the same sort of migration as Minolta to cope with in-lens motors and aperture solenoids. Pentax took the same route with K-mount.

The Minolta 9000 didn’t floor Nikon and Canon, who still led the professional 35 mm market. Minolta tended to do a ‘professional’ body update every other generation of cameras. These included the (unconventional) ‘9xi‘ in 1992 and the ‘9‘ in 1998 – two cameras that demonstrate very different design methodologies. These cameras are, justifiably, very highly regarded, but were probably outsold by products with Nikon and Canon on the front.

The Honeywell postscript

Back in the 70s, Honeywell had tried to interest a whole bunch of Japanese camera companies in their AF system. Most of the companies declined, confident that they could develop their own systems independently.

Honeywell started threatening legal action against Minolta for infringement of their AF patents in the late 80s. Minolta seemed confident in their position. They probably could have settled for a licence at a nominal sum, but they went to court in 1992 and lost. It cost them $127.5M – a lot of money back then. Not ‘go-out-of-business’ money, but plenty enough to hurt.

Honeywell were pursuing another 14 companies at that time. Seven (including Canon and Nikon) settled quickly after the Minolta case (Nikon denied infringements but paid up to make the case go away), bringing in another $124M. Presumably the other 7 also settled quietly after that as Honeywell are said to have picked up a total of over $500M in related infringement claims.

Where are they now?

Minolta merged with Konica in 2003, in 2006 they transferred their camera business to Sony and got out of cameras to concentrate on copiers and business machines.

Share this post:

Comments

Geoff Chaplin on Minolta 9000 – The First Professional Autofocus Camera. Let it bleed.

Comment posted: 19/08/2023

S. Bayley on Minolta 9000 – The First Professional Autofocus Camera. Let it bleed.

Comment posted: 19/08/2023

Comment posted: 19/08/2023

Mark Lewis on Minolta 9000 – The First Professional Autofocus Camera. Let it bleed.

Comment posted: 19/08/2023

I preferred the 9000 to the newer 8000i, despite a slightly slower autofocus. The rewind knob allowed you to rewind and remove a film after the batteries died, and it's design was needed to allow it to work with the other functions built into that side of the top plate. The manual winder allowed for much quieter operation, which was preferable in certain situations and locations.

The winder was more useful for my work than the motor drive, as well as being smaller and lighter, and needing less batteries.

The Minolta glass was also very good, and I had a few different lenses that I could select from depending on the work I was doing.

Comment posted: 19/08/2023

Keith Patrak on Minolta 9000 – The First Professional Autofocus Camera. Let it bleed.

Comment posted: 24/08/2023