A year ago, in February 2020, I had the opportunity to travel through parts of Syria. As it turns out, I was lucky with my timing. This was early in the COVID-19 pandemic. While there were temperature checks at the border between Lebanon and Syria, there was no way of knowing that within months the situation would unfold to be a global pandemic.

My journey took me from Mar Mikhael in Beirut, through Damascus to Homs. From Homs through Al-Husn and then up to Aleppo (I had to take a major detour to the east, as it wasn’t safe to travel north along the M5 from Homs to Aleppo). From Aleppo, back to Damascus via Maaloula.

My primary camera was a Leica M10-P with a 35mm Summilux lens. This was the perfect camera for this type of adventure. The camera was ideal for wide open / high shutter speed shots out the side window while driving, as well as for discreet waist level street photography in the streets of Homs and Aleppo and in the alleys and laneways of Old Damascus. I also used an iPhone 11 Pro, which has a fantastic camera that all but guarantees a decent photo.

In addition to the M10-P, I carried a Leica CL with a 40mm Summicron lens. Atop the CL sat a Voigtländer VC Speed Meter II. Most of the time this camera was tucked away in a satchel. Fiddling with two cameras is more complicated when you need to maintain awareness of what’s happening around you. Nonetheless, I was able to shoot a roll of Kodak Tri-X 400 along the way.

Driving north from Damascus, passing the townships of Harasta and Duma, you can already get a sense of the level of destruction that has been wrought on towns across Syria. Even so, that doesn’t prepare you for Homs.

The level of destruction in Homs is simply heartbreaking. Sections of the city have been completely destroyed. It’s a confronting experience to stand amidst the ruins, knowing that these broken buildings once housed families and businesses.

There are still active threats in Homs, so it’s not advisable to spend too much time wandering the streets. I only managed to get a few shots with the Leica CL in Homs. The shot below shows a commercial area that’s slowly coming back to life with small stalls and markets.

From Homs, we headed west towards Krak des Chevaliers, a crusader castle. The town of al-Husn, below the crusader castle, has been ravaged by fighting. Barely a dwelling is untouched from the pockmarks of small arms fire and shrapnel, or the cavernous holes left by anti-tank rounds.

The drive to Aleppo took me west to avoid the M5 highway, which wasn’t secure at the time. It was a longer route, but significantly more interesting.

Arriving in Aleppo brought home once again the horrors of war in dense urban cities. Entire sections of the city have been destroyed. The Al-Madina Souq—previously the beating heart of the city—was burnt out with parts in ruins. The adjacent Umayyad Mosque, was also destroyed in the fighting and is slowly being restored. From Aleppo it was possible to hear the sound of explosions from the direction of Idlib, where fighting was continuing at the time.

The shot below is taken from the Citadel, looking over the city of Aleppo.

After departing Aleppo, we again took our long detour out east and then south. We encountered driving snow most of the way down. A break in the weather gave us the opportunity to visit the town of Maaloula.

Maaloula is a beautiful town not far from Damascus. The town has a rich history, bloodied by the arrival of the jihadist Al-Nusra Front in 2013. The town is slowly rebuilding, but the damage goes beyond broken buildings. The stories of atrocities in Maaloula are deeply disturbing and will scar a generation. The photo below shows homes built into the mountainside in Maaloula.

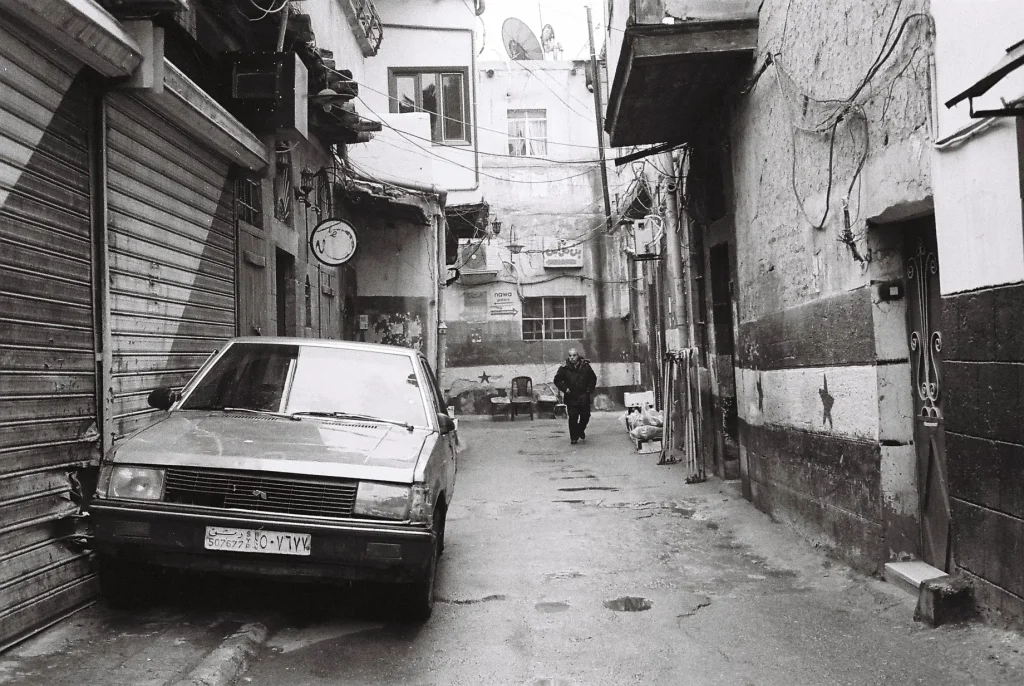

Finally, my journey took me back to Damascus. The Old City is one of the most interesting places I’ve travelled to. The winding back streets are highly photogenic, full of endless curiosities. I took dozens of photos with the Leica M10-P in these alleys, but regrettably only a handful with the Leica CL.

Syria is like no place you will see. It’s equal parts horror and beauty. As stunning as it is saddening and maddening. The experience won’t be easy to forget.

Although the urban landscape has been damaged almost beyond imagination, the resilience of the people shone through everywhere I went. While the battered buildings made obvious photography subjects, there’s also the opportunity witness and document people rebuilding their lives.

The Leica CL is a brilliant little camera. It doesn’t feel as solid in the hand as an M, but it’s the perfect size. The only downside was not having a sufficiently convenient exposure meter. In these types of environments, it’s useful to be able to shoot quick and keep moving.

If you’d like to learn more about Syria, and see additional photos, I wrote a Medium article on my experiences.

I’ve also added the occasional photo to my Instagram accounts – @grantrayner and @grantraynerphotography

Share this post:

Comments

Bob Janes on 5 frames with the Leica CL in Syria – By Grant Rayner

Comment posted: 20/03/2021

Did the internal meter of the CL not work?

Comment posted: 20/03/2021

john andrews on 5 frames with the Leica CL in Syria – By Grant Rayner

Comment posted: 20/03/2021

Oh, wait... tourist is founder of a global security and high-risk environments consulting group... helping large corporate clients “navigate crisis environments”. Not a stretch to suggest the author is part of the military industrial complex, and quite privileged.

I’m respectful of photography, photojournalism, hustling...including blogging. But... a wee bit of awareness is important. Or should we next publish “5 frames testing my Hasselblad using expired film, scenes from an abortion clinic” or maybe “Proving the Leica documents pain & suffering better than any other camera...5 gorgeous b&w frames of starving children in the slums of Somalia”

I know this won’t get published, and you’ve been offended by my criticism before... but WTH dude, hosting privileged globalist dude showing off his M10-P and his access to actual victim communities of globalist violence (without the cover of Journalism privilege), and especially NOW, while we’re all suffering the oppression of global pandemic shutdowns?

We can do so much better than selling out for ad clicks.

Comment posted: 20/03/2021

Comment posted: 20/03/2021

Comment posted: 20/03/2021

Comment posted: 20/03/2021

Comment posted: 20/03/2021

Comment posted: 20/03/2021

John on 5 frames with the Leica CL in Syria – By Grant Rayner

Comment posted: 20/03/2021

Comment posted: 20/03/2021

john andrews on 5 frames with the Leica CL in Syria – By Grant Rayner

Comment posted: 21/03/2021

My point is that an essay proclaiming the novelty/beauty/interesting nature of photographs taken of a bombed society, whether for technical gear or image sharpness or compositional reasons, is by definition “glorifying violence”, unless it serves a justifiable journalistic purpose.

The author should be free to express himself... whether morally blind or intentionally evil, or anything in between....but the publisher carries responsibility for granting the essay an audience in context, as well as exposing the existing audience / influencing the public (such as may happen when remote bombing of cities is normalized as a form of political expression).

A comment citing this essay as “humanizing their situation” suggests documentary journalism, although it’s context (noting that America “screwing over” the victims) contrasts with the author’s comments.

Thanks to the editor for allowing the discussion. Thanks to the author for commenting with more of his own perspective, and at least listening to the ideas. And thanks to the reader, who is likely a photographer/photography advocate, for considering that you are an important part of the world, not simply a remote observer or ancillary creator. What happens “out there’’ is empowered by the collective will (with your consent, expressed or implied).