The best camera is the one you have with you. Now we have camera phones that fit in our pockets: back in the 1950s cameras were larger and were made of materials that were comparatively heavy and bulky. The miniature camera, using 35mm cine stock had been around for some time and was quite successful, but despite the label, it could not be carried everywhere. One solution to this was 16mm film.

16mm Film

Post-war there was a market for pocketable cameras. Cameras that would allow a photographer to record what they saw as they went about their day. 16mm cine film stock was common and optics for the format were a known quantity. Over time, through the late 40s and 50s a number of tiny cameras appeared that used 16mm film. Sometimes referred to as spy cameras (along with the Minox cameras that use even smaller film), sometimes simply as subminatures.

Differences to 110

Although the film size is the same, there are notable differences between older 16mm implementations and 110 film. The older 16mm systems lend themselves far more to DIY loading. 110 film has non-cine perforations and is pre-exposed with frame lines and numbers (look at a 110 negative and you will see that the perforations and spaces between frames are dark). Most of the serious 16mm systems used a pressure-plate to keep the film flat against the gate. For whatever reason, Kodak did not include a pressure plate in the 110 cartridge. Maybe with the depth of field available from the relatively wide lenses used, they just thought a pressure plate unneccessary.

One Format, Many Implementations?

16mm film comes in a number of flavours; unperforated, single perforated and double perforated. Lots of variety. Lots of different ways of handling the film and keeping it away from light until the right time.

The following is a brief summary of some of the 16mm stills implementations. More comprehensive information can be found at the excellent resources www.submin.com and www.subclub.org (if you get to a Glaswegian music venue, you have got the domain suffix wrong).

In the beginning…

Fotex-Kameras made the first of the more sophisticated 16mm cameras, called the MiniFex, in 1932. Manufactured in Berlin, the camera used unperforated roll film with a paper backing and took 13x16mm images.

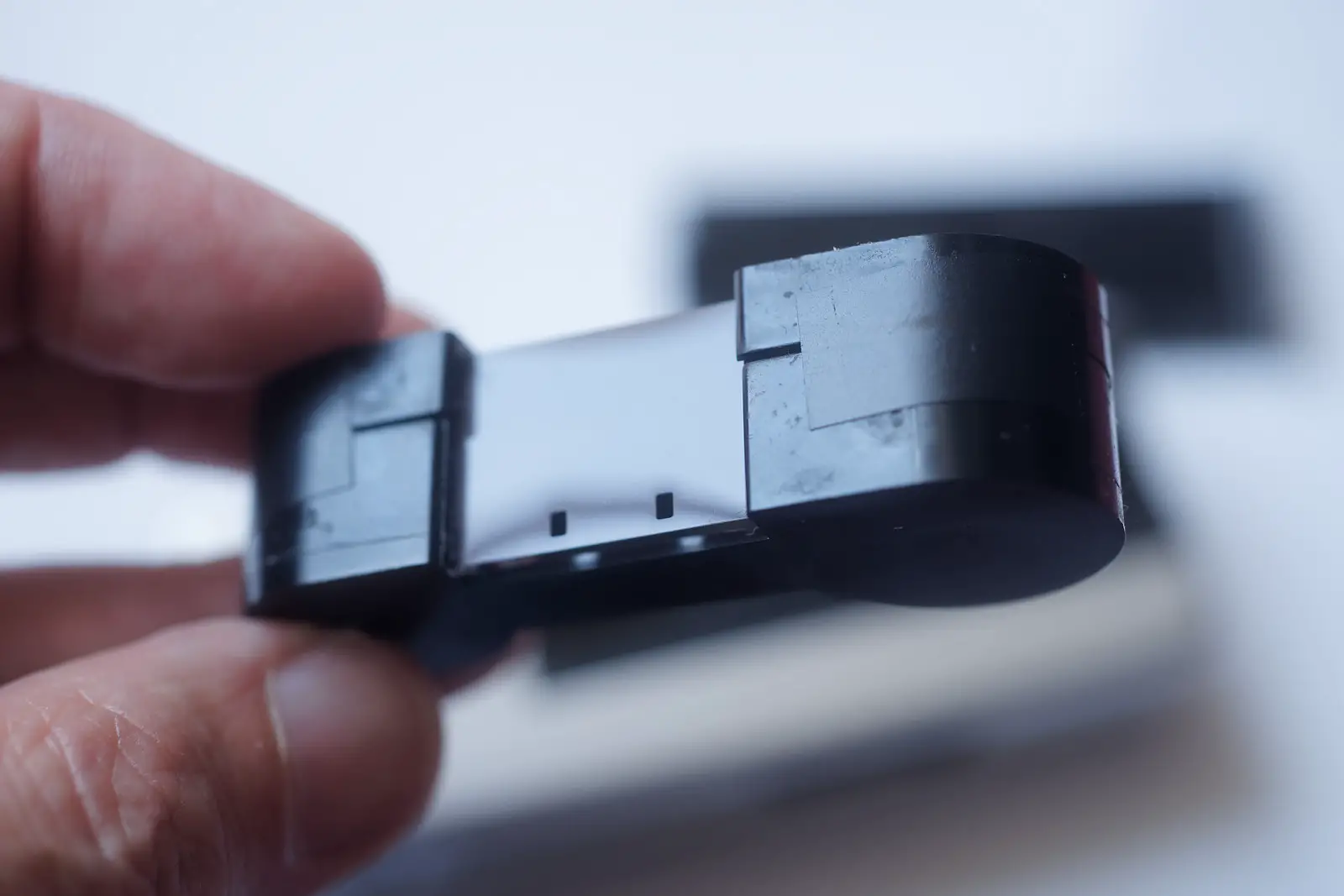

RADA cassette

The RADA cassette uses single perforated 16mm film. The ‘kit’ for a film includes a tiny light-tight cassette and a take-up spool. Images are 12×17 mm. Film is wound back into the cassette once it has been exposed. A number of cameras used this cassette, including the Wirgin Edixa 16, Alka 16, Franka 16 and the Rollei 16. Of these, only the Rollei uses the perforations to advance the film.

Mamiya 16 cartridge

The first Mamiya 16 camera turned up in 1949. Originally it used an arrangement feeding 16mm film stock between two identical light-tight mini-cassettes. Later versions put a bridge between to two chambers to form a cartridge which looked more similar to the (incompatible) Minolta 16 cartridge. Frame size was 10×14. Mamiya carried on production into the 1960s and included versions branded ‘Tower’ (for Sears) and Revue.

GaMi

Galileo Milan produced a 16mm camera in 1953. It used a double cartridge in metal and shot 12×17 frames on unperforated film. It was a high-end camera and production ceased in 1965.

Goerz Minicord

Another high-end camera. Slightly bigger than the others – a twin-lens reflex the size of a packet of cigarettes (a common source of comparisons back in those days). Double perforated film was held in a double cassette (sometimes joined). It took 10×10 mm square shots.

Minolta 16 cartridge

The Minolta 16 cartridge was about the closest that 16mm got to a standard before 110 swept all before it. Initially it gave a 10 x 14 mm negative on double perforated film, which is held in a two chamber cartridge. Later models from Minolta used single perforated film in the same cartridge, giving 12×17 mm negatives. As well as Minolta; Yashica, Olympus and Kiev also used the same basic cartridge at various times. Minolta released the last of these cameras in the 1970s as an attempt to compete with 110. All a bit David-and-Goliath. Production of film ceased in 1996.

Using Minolta 16 cameras in 2021

I stress I’m not going deeper on the Minolta 16 cameras because they are any better than the other 16mm systems. They are simply the ones I have access to.

Using these cameras in the present day is not as difficult as one might think. Minolta produced film in compatible cartridges until 1996 (Minolta never actually made the film, but they did package Kodak film in their own cartridges). Yashica, FD and Kiev also produced cartridges (although Kiev type 2 cartridges cannot be used in non-Kiev cameras). Minolta sold empty cartridges at 25 cents a pop in the US after production stopped.

The Cameras

I have two Minolta 16 cameras, and it is those I’m going to be mainly talking about. However, it is probably worthwhile giving you a rundown on the range of ‘16’ cameras Minolta made.

Automat

Minolta launched the ’16 Automat’ in 1955. It was based on an earlier camera from 1950 called the Konan Automat. Minolta helped with development and manufacture of the Konan camera and later bought up the rights. Minolta changed the original Konan 16 cartridge (the two are not compatible). The Automat operated on a push-pull film advance like the little spy Minox cameras.

Sweet 16

Minolta produced a version called simply ‘Minolta 16’ in 1957. It featured an f/3.5 lens with speeds of 1/125, 1/50 and 1/200. It was available in six colours . An improved version (‘Minolta 16 II’) with a highly regarded f/2.8 lens and speeds up to 1/500, was introduced in 1960. This camera was still current 10 years later.

Back to basics

The ‘Minolta 16 P’ was a simplified model with an f/3.5 lens, introduced when the 16 II came out. It featured thumb wind (less wasted shots if you changed your mind after looking through the viewfinder) a single shutter speed (1/100) and manually set apertures (set according to a manual calculator on the camera body). The follow-up ’16 Ps’ in 1965 added a second shutter speed for flash synch (1/30).

Auto exposure

One follow-up in 1962 was a larger auto-exposure model, with an f/3.5 lens and a selenium cell meter. In 1964 Minolta upgraded to a battery powered Cds cell. These were the ‘Minolta 16EE’ and the ‘Minolta 16 EE II’.

Sleek and practical

The ‘Minolta 16 MG‘ of 1966 was an attempt to get back to a really small body. It had an f/2.8 lens, and a selenium cell match-needle meter. A programmed set of shutter speeds and apertures went from 1/30 at f/2.8 up to 1/250 at f/16.

The Unicorn

Minolta displayed the ’16 Electro-Zoom-X’ at Photokina in 1966. This was an SLR camera with a 30-120 f/3.5-f/16 zoom lens, TTL metering and auto and manual exposure controls. These amazing cameras used the Minolta 16 cartridge to produce 12×17 images. It looked like a cross between Minolta’s second 110 SLR and their later Z-series Dimage cameras. Minolta made three prototypes: It never made it to market.

Pushing the envelope

The follow-up to the MG was released in 1970. ‘The Minolta MG-s’ was given a Cds meter and shutter priority automatic with a manual over-ride. Speeds went up to 1/500. The negative size was also increased to 12×17 (closer to 110), but this does rely on the use of single-perf film.

The ‘cutie’

The final throw of the dice in 1972, just before the 110 format was launched, was the ‘Minolta 16 QT’. This had reduced shutter speeds (max 1/250) but expanded small apertures down to f/22. It also reverted to an f/3.5 lens which zone focused from 1.1 to 10 meters. Although it had a good spec and lens in comparison to most 110 competitors, it was more expensive, as was processing for films.

Pros and cons of the Minolta 16 series

On the plus side:

- You can get film and load your own cartridges relatively easily.

- The cameras can be amazingly compact.

On the minus side:

- It is a small format. Very small. 110 is small, this is smaller. The two I’ve been using produce a 10×14 negative.

- There is little control over differential focus. However, with lenses in the 20-25 mm range, differential focus not a big factor (especially because…)

- The lenses are (with the exception of the one in the QT) fixed focus. Focus is set around 14 ft. If you want to shoot something close up at a wide aperture, you need to use a supplemental lens (built in on certain models). If you want infinity focus, you need to choose a small aperture.

In practice

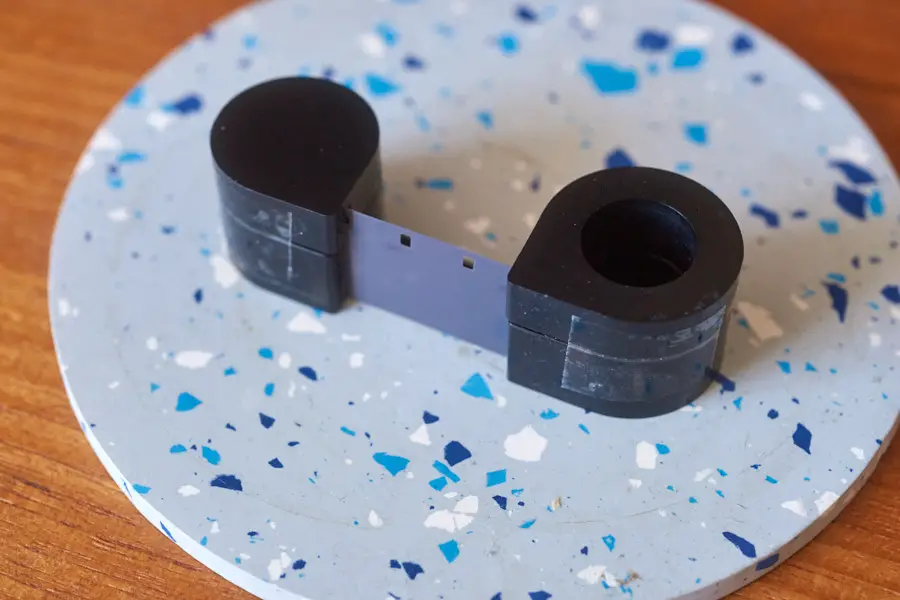

Cartridges

Empty Minolta 16 cartridges are still available, but they cost a bit more than 25 cents these days. The cameras are more common than the cartridges. If you can get both together, great. The cartridges are designed to be disposable, but are easily reloaded with readily available 16mm film.

I had been warned that ‘Made in Germany’ cartridges were of lower quality and leaked light. I had one original Minolta cartridge and one German one. Sure enough the ‘Made in Germany’ version leaked light. Quite a lot of light. I lost about half the shots from the beginning and end of the roll. If it is all you have, maybe try loading and unloading the camera in a dark-bag.

Getting film

Although 16mm film is available, you might have to buy it in 30m reels (expect to pay about £48 for B&W negative film at UK counter prices). That is enough film for well over 50 films. Foma do a 10 m roll of Fomapan-R (reversal film), but when I tried it, the base came out a bit dark when processed for a negative image.

The knives are out

It should be relatively easy to slit down your favourite 120 or 135 film to fit. For myself, I’m not fully comfortable with the concept of sharp knives and fingers being in the same dark bag together. An early attempt led to a cut in the inner portion of my dark bag (since sewed and patched). Attempts to sandwich film between two surfaces to exclude light while a cut was made in dim light led to more light bleed than I’d been expecting.

People do manage the film slitting thing. They seem to do it very well. I splashed out and bought myself 30 m of film cheap off an auction site. Measuring 20 inches of film off a big roll is far easier and gives me fewer worries about trips to A&E or washing blood stains out of a dark bag. If anyone needs some lengths of single-perf 16mm Eastman Double-X 7222, feel free to get in contact, I’ve probably got more than I need.

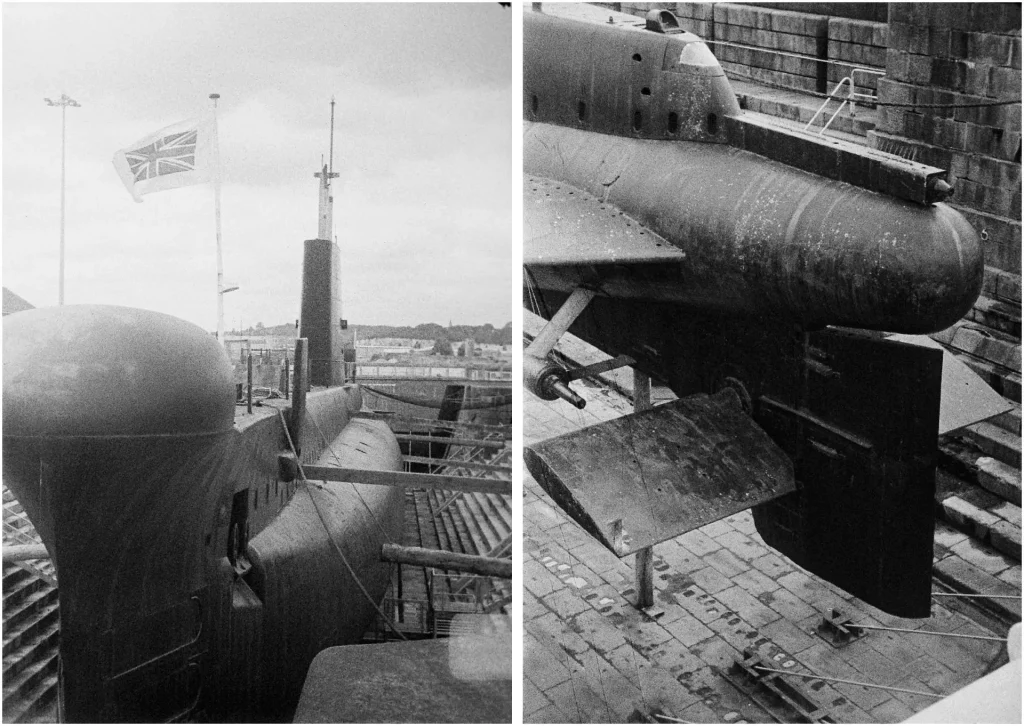

The Minolta 16 Ps

This is a tiny camera with a 25 mm f/3.5 Rokkor lens. You get a choice of two shutter speeds, which are selected by a lever on the front. The slower speed is designed for flash synch, but it can be used for a bit of extra exposure flexibility. The camera includes a manual exposure calculator. You input the ISO of your film and the calculator suggests an aperture based on weather conditions (a sort of ‘sunny 16-plus’). Suggestions are only made for the top (1/100) shutter speed, but it is relatively simple to double the f-stop to get the 1/30 speed.

The thumb-wind is a simplification of the earlier push-pull operation and should save film (the push pull of the earlier cameras advances the film even if you didn’t take a shot). The thumb-wind works well, but if you wind-on then change your mind, you are at the mercy of the very sensitive shutter button. Slip it into a pocket with the shutter cocked and you will likely end up with a picture of your pocket interior. The film counter resets automatically when you open the back and counts down from 20. The viewfinder is a simple tunnel.

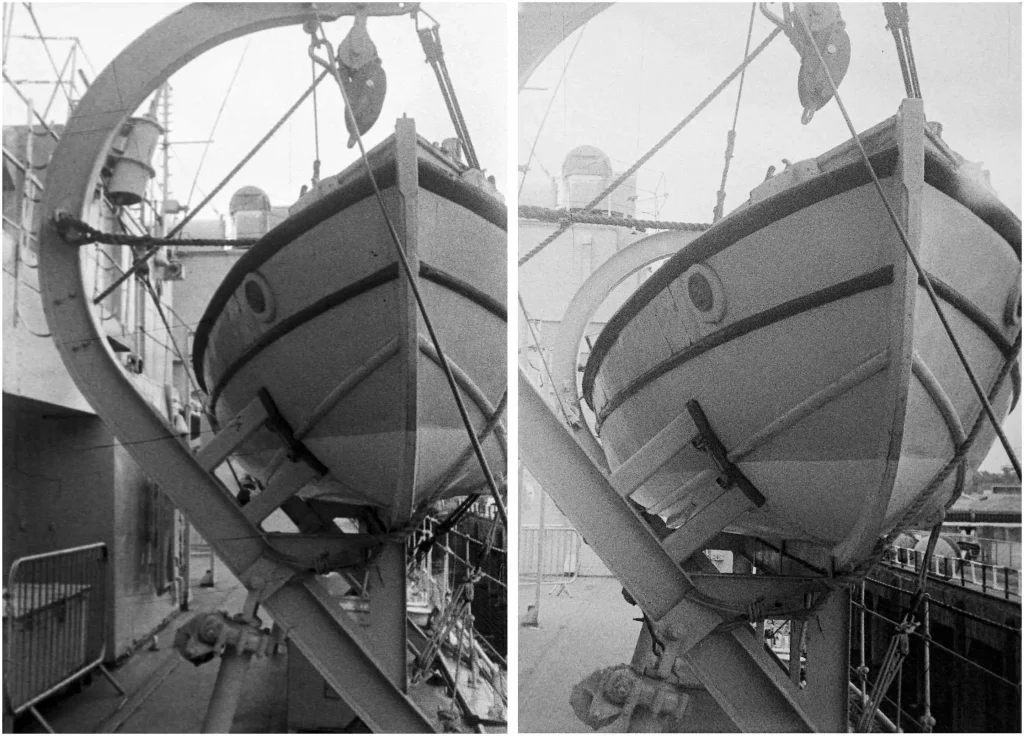

The Minolta 16 MG

This is a small but solid camera. It has a built-in close-up lens that shifts focus to about 4 ft and a sliding lens cover that protects the lens and locks the shutter. The coupled programmed manual exposure works very well, choosing values steplessly from 1/30 at f/2.8 to 1/250 at f/16. It did take me some time to work out how to set the ASA/ISO (you just push the dial beyond its stop and ASA values go up or down depending on direction). Match the needle once for a lighting situation and you can probably forget it until you notice a change in light. at 20 mm, The Rokkor lens is a little wider, as well as brighter, than the Ps. The viewfinder has more optics and incorporates a bright-line frame with parallax marks.

The wind-on dial on top of the camera works well and incorporates a film counter that counts down from 20, showing you how many shots you have left with a red arc. Also on the back is a control for setting flash synch and the door release. When set for flash the shutter speed is 1/30, but the aperture remains linked to the dial on top of the camera, which gives some extra manual control if you wanted a small aperture. The camera has a tripod socket on one end and a flash synch socket on the other. The tripod socket has a detachable ring around it that allows you to fit L-shaped filters over the taking lens.

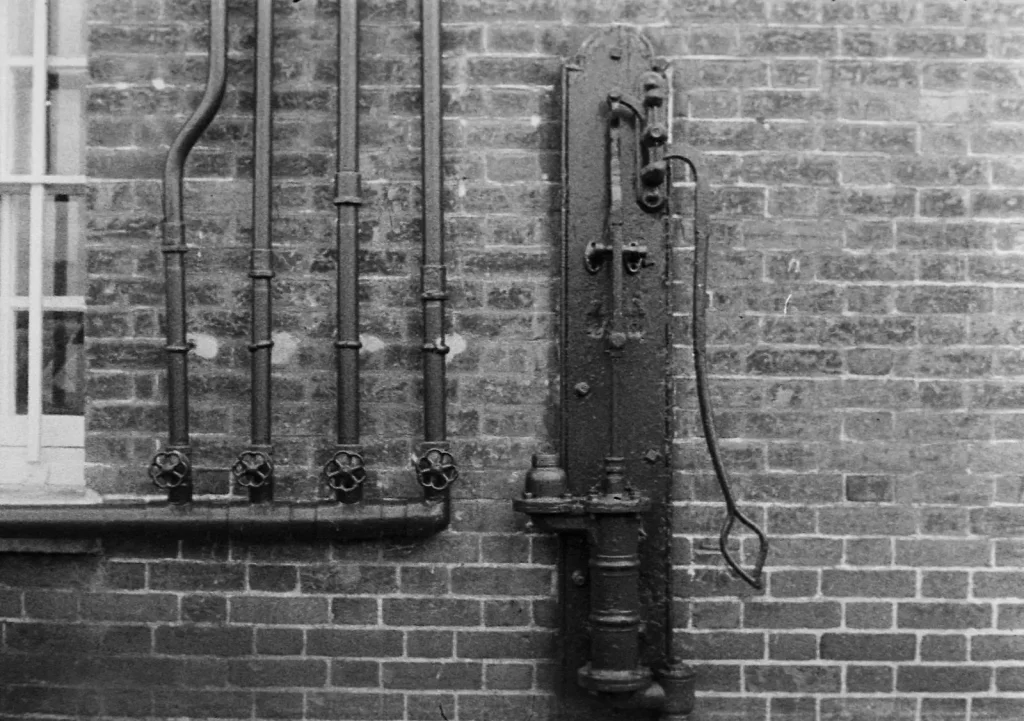

The results

Practical in 2021?

In practice these are very usable cameras. The lenses are good quality, you can get film without breaking the bank and they are compact enough to carry with you most places.

Of all the 16mm formats, the Minolta 16 cameras are the most affordable and easiest to source film for, but some of the other brands mentioned above are also lovely tiny instruments and most of them focus as well.

All of these 16mm cameras are primarily aimed at documentary photography. Other than composition, there is not a lot of scope for creative control. The negative is really small. You really need to embrace grain, even with careful processing. Experienced subminaturists claim to get quality 8×10 prints from negatives even smaller than these; that would require skills beyond my own, but doubtless it can be done. A practical example of just how good some processing can be on these small negatives can be found in Julian Tanase’s article on the 8×11 Minox cameras.

In purely practical terms we should be using a camera phone. But then, if we were so obsessed with the practical, we would be using digital cameras all the time rather than film…

There is a challenge in producing an image with basic equipment and being creative without creative controls. Shooting Subminature 16mm film certainly supplies challenge.

Share this post:

Comments

Ronald Piet on 16mm Film – Shooting Subminature Film in 2021 – By Bob Janes

Comment posted: 20/07/2021

I had walked into a camera store in Toronto, Canada, where I bought one with a partially exposed roll of colour print film in it. The owner's son had discovered it would cost $25 to have it processed in NYC. I finished off the roll myself over the weekend. I had determined the film was Kodak stock, C-41 process, so I processed it myself. I already had a 110 mask for printing, so after a few minutes of black paper and a knife I printed the entire roll. As a courtesy, I returned to the camera store with the prints that they had shot.

Needless to say, their jaws dropped to the floor.

I also has a Pentax 110 slr, and I can inequivalently state, because of the pressure plate that is in the Minolta, the image quality was noticeably better with the Minoltas.

Comment posted: 20/07/2021

Jordi Fradera on 16mm Film – Shooting Subminature Film in 2021 – By Bob Janes

Comment posted: 20/07/2021

I will not do the article because apart from the difficulties to obtain the film I have seen some images on the internet where a circle surrounded by black is seen.

In simulations with translucent tape the same thing happens.

Despite having multiple shutter speeds and multiple apertures and being beautiful, it's a real disaster. It is like a children's toy.

However, it will soon participate in a future article along with other cameras of its time or older.

Comment posted: 20/07/2021

Terry B on 16mm Film – Shooting Subminature Film in 2021 – By Bob Janes

Comment posted: 20/07/2021

As you say, the lens is fixed focus, and true infinity focus can only be achieved at f16, about 200ft at f11, but Minolta issued a set of 2 close-up lenses, and which included a third labelled "O" is specific for infinity focusing at all apertures. This "O" lens greatly improves the versality of the 16 II.

Comment posted: 20/07/2021

Neal A Wellons on 16mm Film – Shooting Subminature Film in 2021 – By Bob Janes

Comment posted: 20/07/2021

I process 16mm on a currently available Yankee reel that is adjustable from 120 to 16mm with tank. I take the reel out and use it in my Patterson tank so I can invert to develop and wash.

Comment posted: 20/07/2021

Comment posted: 20/07/2021

Rock on 16mm Film – Shooting Subminature Film in 2021 – By Bob Janes

Comment posted: 20/07/2021

Comment posted: 20/07/2021

Comment posted: 20/07/2021

Nigel on 16mm Film – Shooting Subminature Film in 2021 – By Bob Janes

Comment posted: 23/07/2021

Serhiy on 16mm Film – Shooting Subminature Film in 2021 – By Bob Janes

Comment posted: 05/08/2021

I had Kiev-30M when I was 12, and it was still USSR, it's last years. First, 35mm film disappeared in stores, then 16mm, then chemicals.

So I also got 16mm reversal movie film, cut it and half-processed with standard developer.

Pos on 16mm Film – Shooting Subminature Film in 2021 – By Bob Janes

Comment posted: 09/04/2022

Are marked 'Made in Germani'. Kiev 16 cassettes do not fit Minolta 16.

Goerz Minicord III - Camera Collector Pages on 16mm Film – Shooting Subminature Film in 2021 – By Bob Janes

Comment posted: 12/09/2022

Comment posted: 12/09/2022

Tom Deveron on 16mm Film – Shooting Subminature Film in 2021 – By Bob Janes

Comment posted: 06/08/2023

Don on 16mm Film – Shooting Subminature Film in 2021 – By Bob Janes

Comment posted: 01/09/2023

But primarily I liked using them - they were so well made!

Stumbled on this site but thanks for the memories!