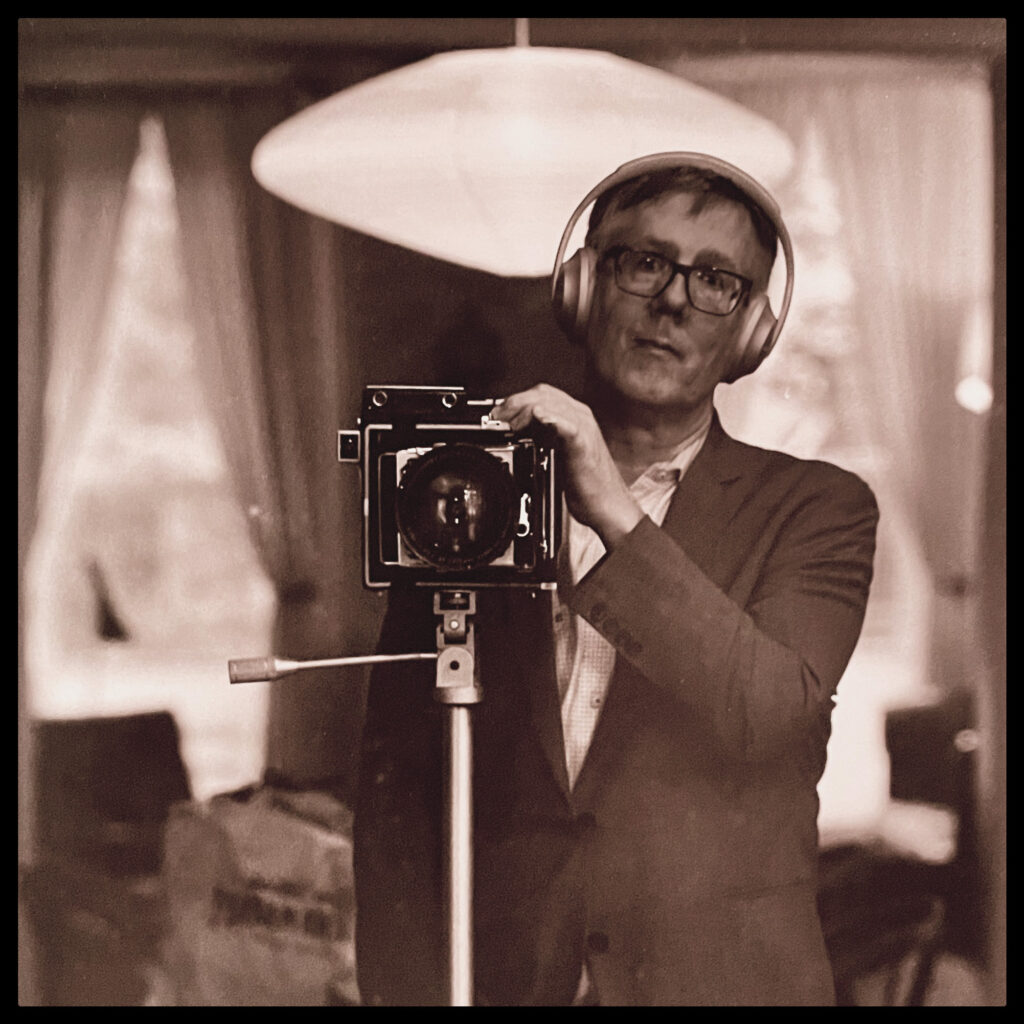

For the New Year, I am plotting a significant shift in my approach to film photography. Rather than moving from camera to camera, pivoting from 35mm to medium format or even 4×5″ from one day to the next, I’m planning to make a commitment to one camera — just one! — for 2025.

Before revealing, in a future post, which camera I’ll be using for the next 12 months, I must take an honest look at why this new year’s resolution makes me uneasy. Like some other photographers who’ve rediscovered the medium over the past decade, my return to film came in middle age, a dangerous epoch when a somewhat higher disposable income, a nostalgia for things past and creeping intimations of mortality can combine to produce significant, at times comical, material excesses.

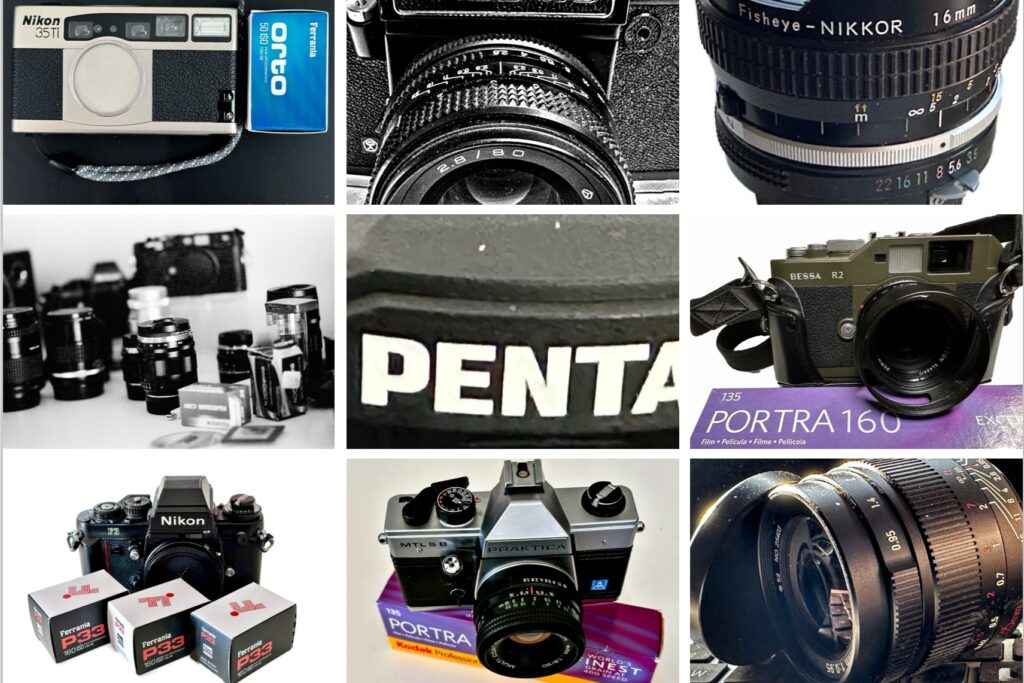

Moving back into photography and to the darkroom in 2019, my desire to make and develop my own photos after decades away ran headlong into the maw of the internet. Of special note is the inescapable online auction site (you know the one), where I’ve acquired, sold and repurchased a near-warehouse full of gear, becoming in the process a reluctant poster child for the previously unfamiliar (to me) mania known as Gear Acquisition Syndrome. While I avoid most social media, an equally impactful force has been YouTube, where a phalanx of film photography “influencers” — some encouraged by camera retailers; many young enough to be my children — wax rhapsodically about their favorite vintage cameras, lenses, films, techniques and accessories (in the process sharing photos that are often lovely, at times inspiring).

To say that my six recent years of shooting film have been only “about gear” would be an overstatement (at least so I hope). Yet still, there’s the palpable sense of anxiety that settles in my gut whenever I contemplate selecting just one camera from my collection to use on every occasion over the next twelve months.

It’s not the kind of dilemma that plagues most professionals.

My friend Lloyd Wolf, a 50-year photographic veteran who long ago made the transition from film to digital, rarely thinks about alternative items of kit, so immersed is he in meeting his own high standards, satisfying his clients and moving onto the next project. (On aesthetic grounds, Lloyd did return to film some years back, dusting off his Mamiya C330 for an award-winning project on Holocaust survivor couples. He told me that he felt that a film TLR might be more familiar and reassuring to his subjects than his bulky digital camera).

As a dedicated amateur, I have not been forced by a daily photography workflow to trim my gear into a coherent package, or indeed to define what my preferred subject matter (or “artistic vision,” if indeed I possess such a thing) might be. Family photos, landscapes, portraiture, travel: I’ve done ’em all, with varying degrees of success (and many, many screw-ups).

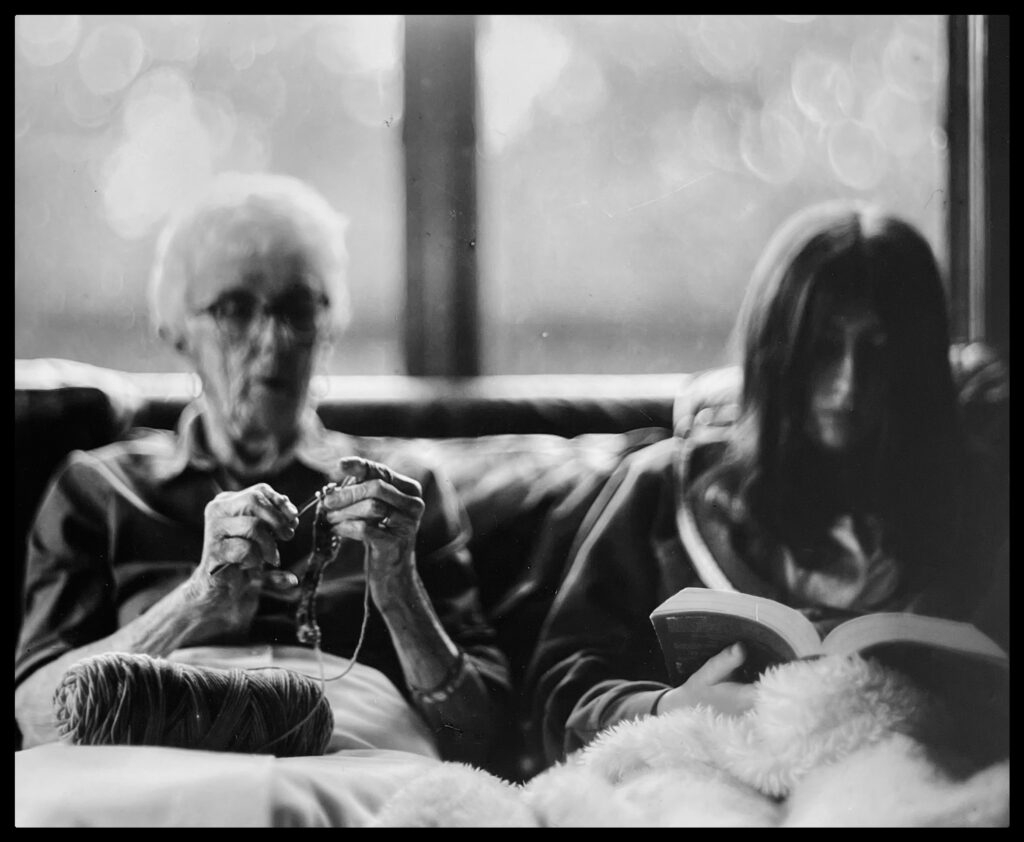

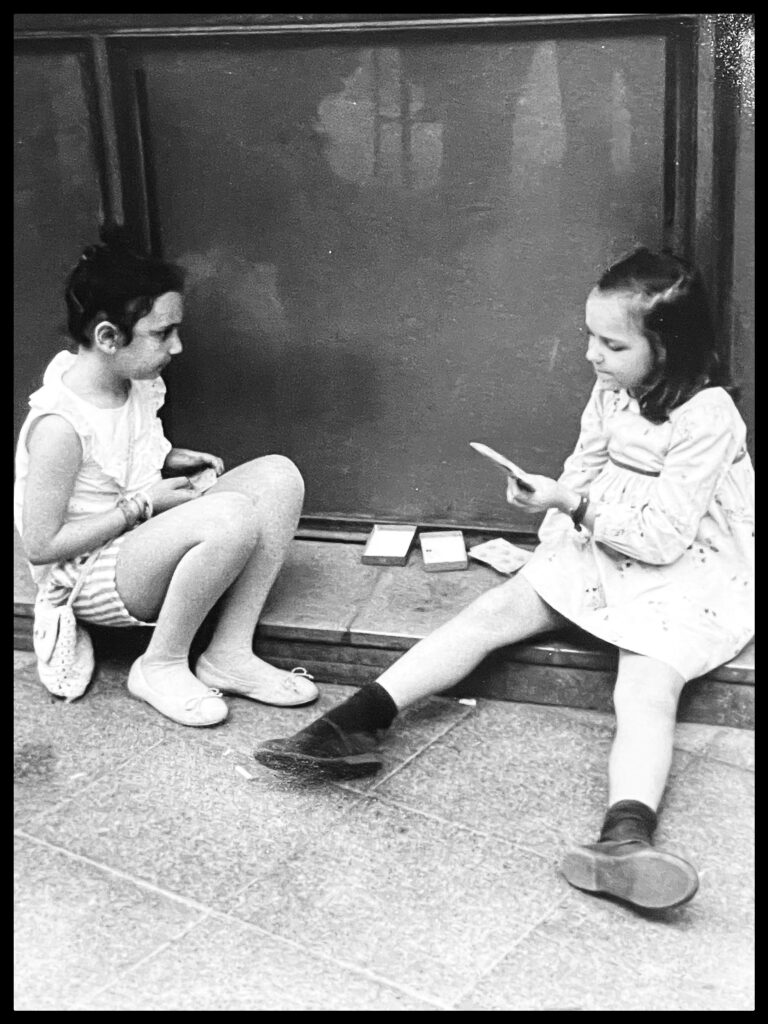

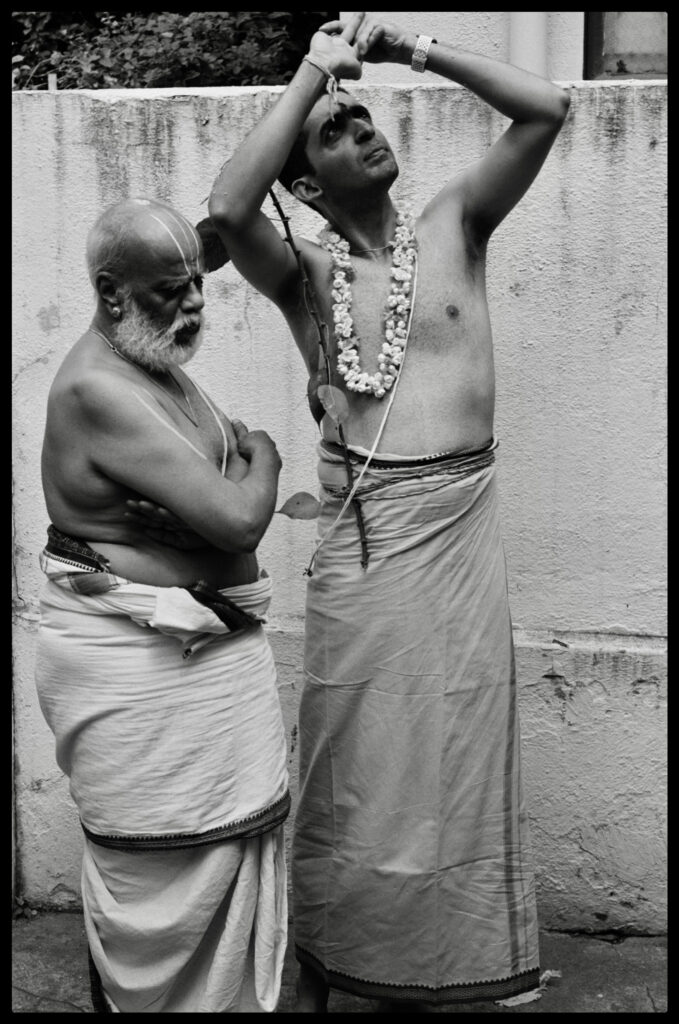

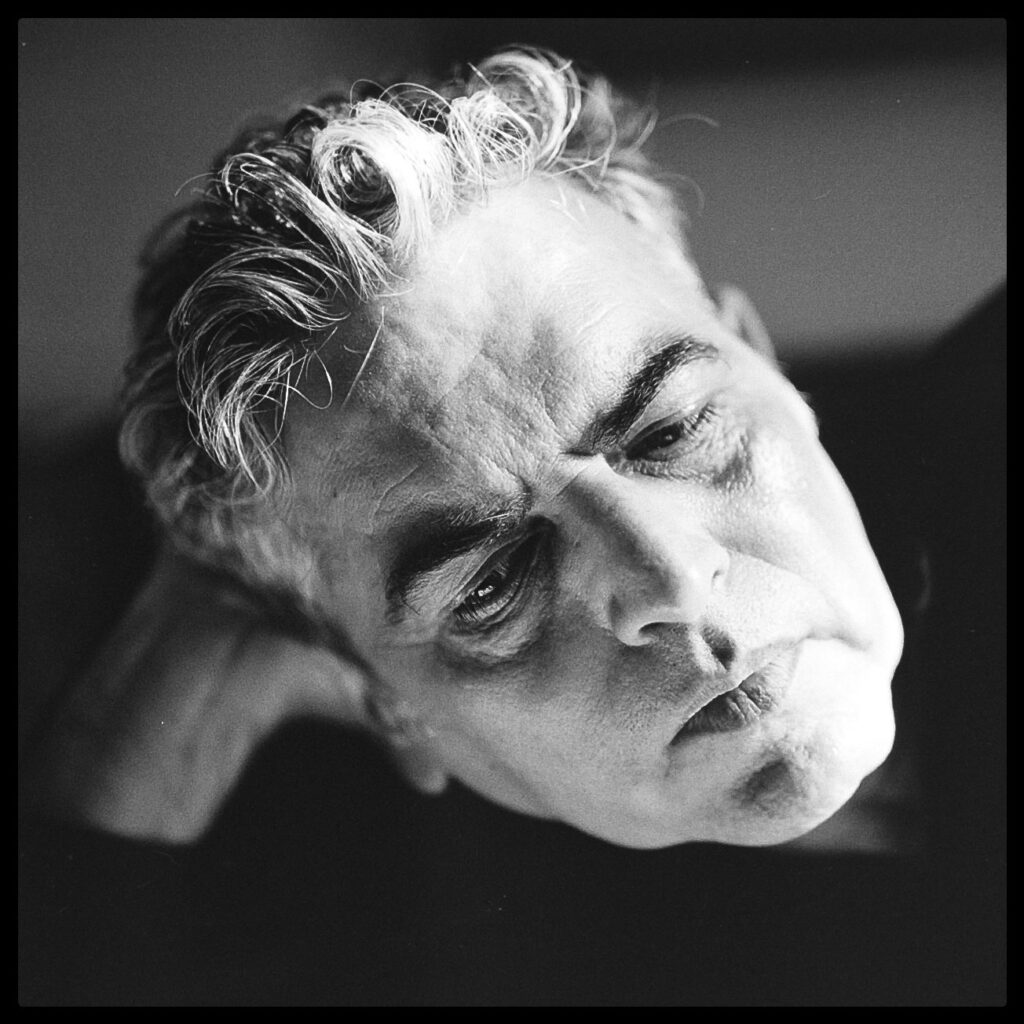

Among my favorite images from the last six years are the following:

If there’s a common aesthetic thread uniting these images, taken in varied locations on six different cameras, I’ve yet to find it. Yet the experience of making them was in some ways similar: I felt that gear was for once subordinate to something larger, each camera a mere framing device that helped me lift a moment from everyday life and make it a tangible object worthy of future reflection. This is, I suppose, a succinct, if somewhat pretentious, expression of what most photographers aspire to: a kind of Platonic ideal striven toward yet seldom reached.

While the cameras do play a part in the look of each of these compositions (could I have gotten such a shallow depth of field on Grandma’s hands with a different bit of kit?), at present my profusion of gear feels less boon than burden. Like a tennis player who changes racquets after every lost point, I have taken to switching from one camera to the next each time I am disappointed with the results of a shoot. This gear preoccupation has kept me from delving more deeply into other matters — banter with subjects, choices of light, film, framing — that almost every writer of note agrees are key to deepening one’s photography.

Being less of a midlife “spoiled brat” — setting aside gear-obsession; focusing on technique; learning from failure — are what’s leading me to shelve most of my cameras and select just one to be my faithful companion for the New Year.

In my next post (later today), I’ll reveal which camera I’ve chosen and what I hope to get from using it in 2025.

Share this post:

Comments

Peter Kay on A New Year’s Resolution: One Camera for 2025

Comment posted: 21/01/2025

Comment posted: 21/01/2025

Jonathan Leavitt on A New Year’s Resolution: One Camera for 2025

Comment posted: 21/01/2025

Comment posted: 21/01/2025

Jeff T. on A New Year’s Resolution: One Camera for 2025

Comment posted: 21/01/2025

As you will have guessed, some, often young, amateur photographers use(d) one camera in the film era out of necessity because that's all they (we) could afford. Back in the day, our small amount of disposable income went to purchase an additional lens for it. And, if we had professional ambitions, after accumulating a few lenses, then an additional body that would mount the lenses, so that at times in certain shoots we'd have two bodies hanging off our necks and shoulders, each with a different focal length lens mounted. I remember when I finally was able to afford a film SLR with a 50mm f/1.8 lens as a grad student in the late 1960s. I spent several months getting used to its possibilities and limitations, especially in low-light photography. My next purchase was a cheap, used, Vivitar wide angle lens, which better enabled indoor photography, and forced me to think more about artificial light. Then I saved for my next purchase, a Vivitar telephoto lens, which was a revelation. In short, even in sticking with a single camera, a new lens opens new possibilities and changes one's relationship to their camera, but it doesn't introduce the kind of confusion that can arise when switching cameras, lenses, and formats.

Comment posted: 21/01/2025

Comment posted: 21/01/2025

Comment posted: 21/01/2025

Comment posted: 21/01/2025

Gary Smith on A New Year’s Resolution: One Camera for 2025

Comment posted: 21/01/2025

Like Jeff mentions, 50 years ago I only had a single camera (Canon FTb) with a single lens. I did however also have an enlarger and darkroom set-up.

When I decided several years ago to return to film, I went with what I knew: a Canon FTb with that 50/1.8. It turns out that it remains a pretty good film camera despite not doing everything that digital bodies do. In the last month, I've added my first Nikon from that same era and there are things about the Nikon that are pretty cool. I've shot with waist-level finders but even with my glasses my eyesight these days is pretty poor. Weight is also a factor - the Mamiya 645 is a heavy beast to wander around with.

I can't see myself being limited to a single camera. To me, there doesn't seem to be a point to the limitation.

Comment posted: 21/01/2025

Comment posted: 21/01/2025

Ibraar Hussain on A New Year’s Resolution: One Camera for 2025

Comment posted: 21/01/2025

given me some ideas.

And of course really liked the photography, the compositions and everytthing! Masterful

Comment posted: 21/01/2025

Rich on A New Year’s Resolution: One Camera for 2025

Comment posted: 22/01/2025

Have fun!