Aren’t humans amazing. We develop sophisticated technology – high-resolution sensors, superfast lenses – to record images. But we also make, and express ourselves with, the simplest of homemade devices. Even with the most limited materials – cardboard, beercans, tape – the urge for creative expression will find a way. And this is where we end up. A camera which makes 17 simultaneous exposures on a single sheet of paper. A four-week long exposure – two weeks in New Jersey and two weeks in Minsk. A camera made from a pistachio nut (yes, a pistachio nut). Photos made with homemade cameras with no lens, and – except in two cases – without conventional film. Hang on to your hats: things are about to get interesting.

How did it come to this?

It all started harmlessly enough. Earlier this year, I took part in a collaborative project on lumen printing, an alternative photographic process. Some of the other participants were into pinhole photography, and infected me with their enthusiasm (though to be fair, I’m a sucker for this sort of thing anyway). Before long, I had made a pinhole “lens” for my digital camera, then a cardboard pinhole camera to make images on photographic paper (which failed), and another cardboard camera (which worked).

Now that I had a working camera and, obviously, a long list of things I wanted to try, I thought it would be fun to document my… learning journey sounds a bit self-important, but I suppose that’s what it is. Accordingly, I pitched the idea to Hamish: the first post of my “Pinhole Adventures” series would be about building my cardboard camera, and subsequent posts would be about wherever my experimentation led me.

So is this post about building my camera? Well no… Somewhere along the way, I got the bright idea to ask my Facebook pinhole group to share some photos of homemade cameras for inspiration, along with images made with those cameras. The responses were so interesting that I asked them if I could share the photos on 35mmc. And this how we end up here: Part 1 of the series features neither my camera, nor any of my own photographs.

But in a strange way, it makes sense. Part 1, as it stands, is not about my own build, but about inspiration – and inspiration comes first. Besides, in the short time that I have been part of the pinhole community, I’ve often been struck by the spirit of openness, sharing and collaboration – of the collective over the individual. It thus seems fitting that I start with photos and cameras from the community, which they generously agreed to let me share. The only risk is that my own camera and photos, when they’re eventually featured, look ordinary in comparison.

How it works

Pinhole photography has been featured here before, so 35mmc readers are probably familiar with the idea – in fact, some of you may have more experience than I do. Earlier posts were largely about pre-made cameras (like the Zero 2000), or converting a regular camera (like a Paxette). Of course, these are all excellent options in their own way, but for me, a big part of the appeal was making my own. So my camera, and all the cameras featured in this post, are homemade, with simple materials which most people already have at home.

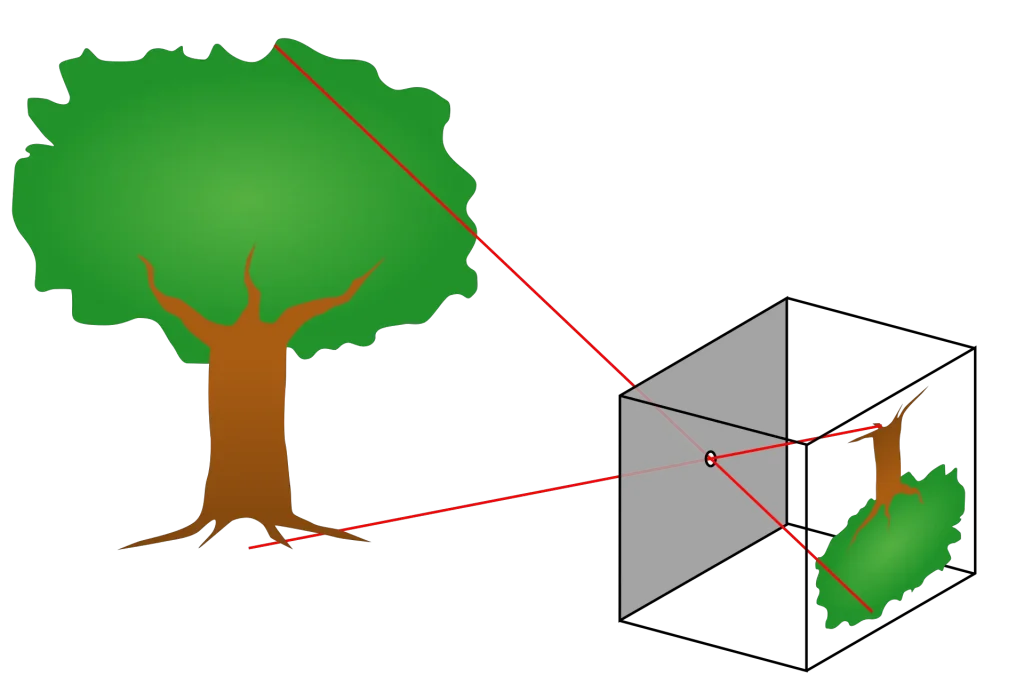

Pinhole cameras make images without the use of a lens. The principle is simple. An otherwise light-tight container has a tiny hole which admits light. Rays of light passing through the hole project an inverted image inside the camera; that image can then be recorded using light-sensitive film, paper or even a digital sensor (the diagram below may be more helpful than my description). I won’t go into too much more detail in this post, but if you’re interested, you can check out the Resources section below.

Pinhole magic

Since I got into pinhole photography, I’ve shown the results of my experiments to various friends and family members, some of whom have never seen a pinhole photo before. Some love it, and some don’t see the appeal; it’s all very well to say that sharpness is overrated, or to invoke that Cartier-Bresson quote, but pinhole photography sometimes asks a lot of the viewer.

Personally, I like the unsharpness, but I can understand if others don’t. I also like the weird and wonderful angles, the distortion, the “infinite” depth of field, and the motion blur that comes from the long exposure times.

And I like the cameras themselves. I find the DIY ethos appealing, but I don’t have any special skills like woodworking or 3D printing. Pinhole cameras, however, can simply be made from cardboard or cans, with nothing more than scissors, tape, a craft-knife and a needle. Three years ago, Hamish wrote a short but incisive piece about the lure of the uncomplicated camera. A pinhole camera, I would argue, is as uncomplicated as it gets. Furthermore, each homemade camera is unique, and there is something about the process of making one which instantly makes you want to experiment more. Made a regular pinhole camera? Now try a curved panorama. Made one from wood? Now paint it. And so it goes.

Last but not least, as I mentioned, I like the community. Over the years I’ve been part of various digital, film photography and darkroom groups and forums, but for whatever reason, pinhole and alternative process groups seem to have more diversity, less gate-keeping and fewer arguments about the “right way” to do things. And a spirit of sharing, which brings me *drumroll* to the cameras.

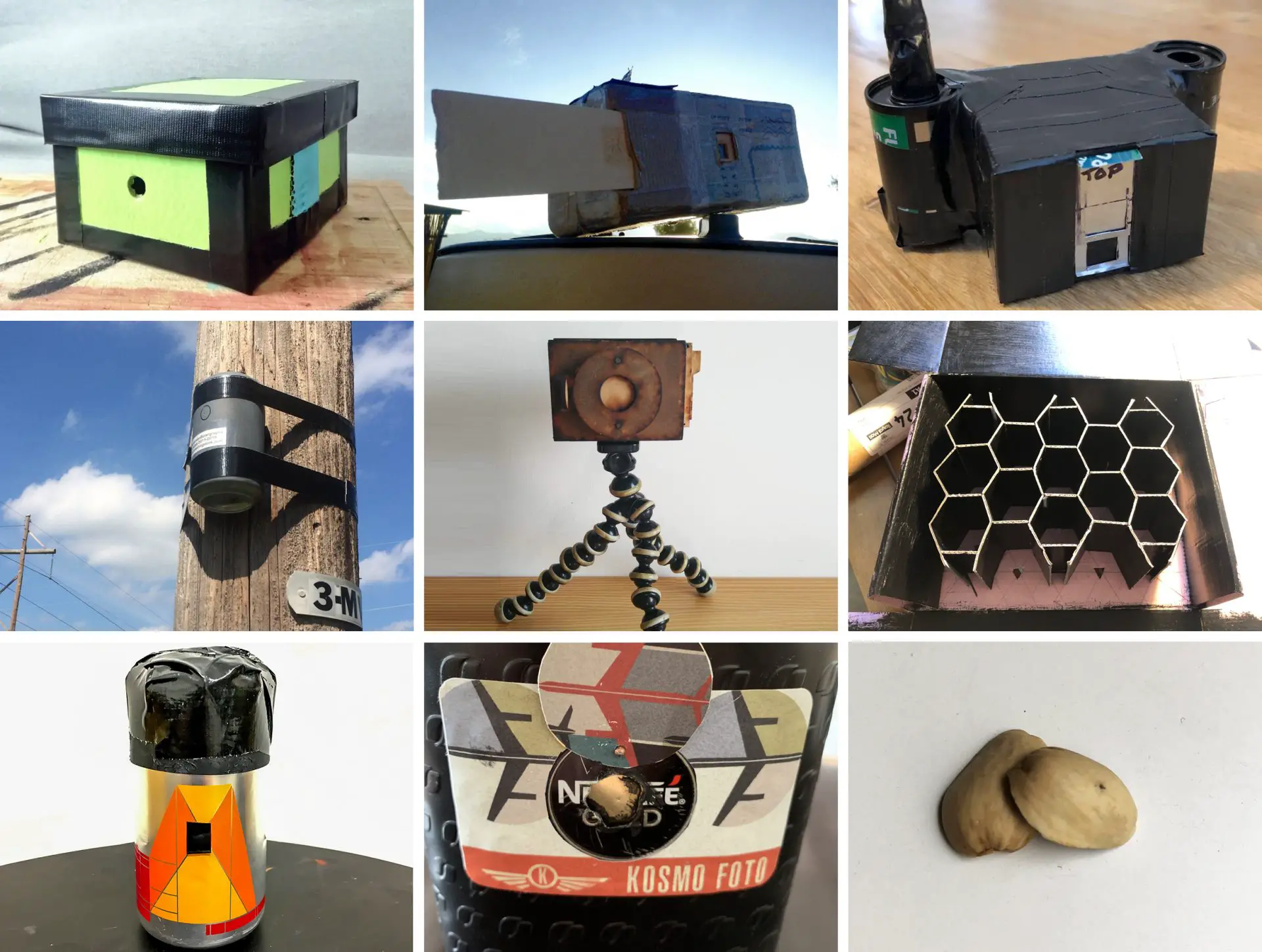

Nine homemade cameras

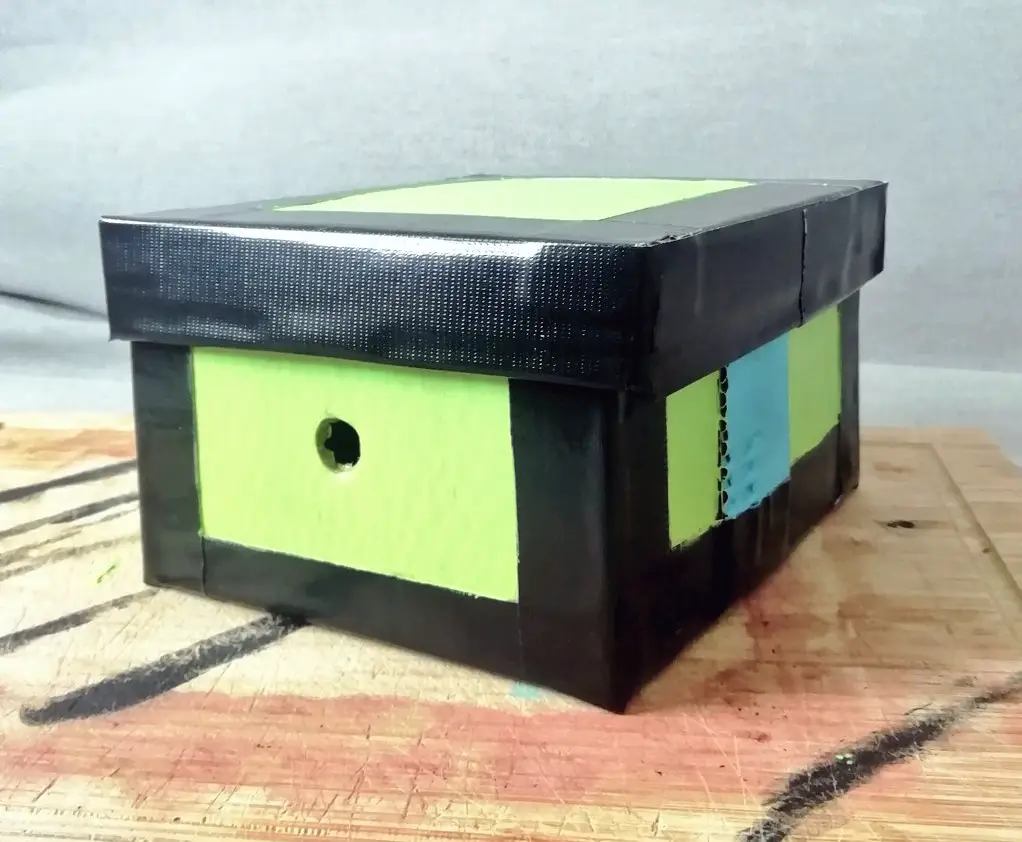

Allysse’s Cardboard Boxcam

Like me, Allysse Riordan (Bristol, UK) is relatively new to pinhole photography. Hers is a cardboard camera – a classic beginner camera like mine, but prettier because it’s painted. She made it in August as part of Jason Avery’s #camerachallenge, and has made a few more cameras since then, including one from an egg carton. “Do I have homemade camera GAS?” she asks. “Is that even a thing?” Yes. Yes it is.

Allysse’s portrait of her partner was taken on Ilford MGRC Deluxe Satin paper. Photographic paper, made for enlarger printing, is photosensitive and can therefore be used as “film”. The resulting prints are “paper negatives” (the paper turns darker where it is exposed to light), but they can be contact printed under an enlarger to get positive prints, or simply inverted in Photoshop.

The paper is slow (Allysse rated it at ISO 3), and pinhole apertures are tiny – often in the f/100–300 range (Group f/64, eat your heart out). To compensate, the exposure times have to be abnormally long; this portrait was exposed for 10 minutes. It seems to me that family, friends and partners of pinhole photographers have their work cut out for them – doomed to be constantly sitting for long-exposure portraits.

More of Allysse’s work: Website | Twitter.

Andrew’s NesPin

Rigid cameras are a step up from cardboard. Andrew Bartram (Cambridgeshire, UK), who hosts the Lensless Podcast (yes, there is a podcast about pinhole photography!) shared his “NesPin”, a coffee can which takes 4×4″ paper or film. He used thin brass for the pinhole, and his top tip is that “coffee stirrers from Cineworld make neat film guides.” The photo he shared is a 6-minute self-portrait in his back garden; like the previous photo, it was taken on Ilford RC paper.

More of Andrew’s work: Twitter | Instagram | Flickr | Blog

Mike’s 35mm Point-and-Shoot

Yes, I suppose you could call this a P&S. Pinhole cameras don’t need focusing, since everything is in focus (critics might say: everything is equally blurry). And there’s no aperture setting, just the pinhole. So point, shoot… and wait, because it’s gonna be a long exposure.

Mike McLean (Brighton, UK) made his camera from cardboard, but unlike the last two cameras which use paper, his camera takes film (as a 35mm compact, it should feel right at home here on 35mmc). His photo was taken last summer at the Brighton Palace Pier. He used Kodak Ektar, which seems to be a favourite with pinhole photographers for its vibrant colours and fine grain. Ektar, with an ISO of 100, is considered a “slow” film, but it is about 5 stops faster than most photographic papers which are usually rated around ISO 3. This allows for blindingly fast exposure times – “only” about 15 seconds for the photo below.

Mike’s pinhole has a diameter of 0.3mm, with an aperture of f/170 (he buys laser-cut pinholes, while the other photographers featured here make their own). But the homemade ethos is still strong – he made a wooden camera holder with a tripod release-plate on the bottom, and the camera is secured to the holder with his daughter’s hair bands.

More of Mike’s work: Website | Instagram

Citlalli’s Cardboard Superpanorama

Next up: another film camera, but a larger format. Citlalli González (Guadalajara, Mexico) does all of her work with two homemade cardboard cameras. They are both designed for medium-format film: one takes 6×6 images, and the other (shown above) takes panoramic 6×18 images. That is wider – both in aspect ratio terms and absolute size – than the Hasselblad XPan and even the Fuji GX17. As Carlos Jurado wrote in The Art of Capturing Images and the Unicorn, one of the advantages of pinhole photography is being able to choose and create formats, without being tied to the ones predetermined by camera and film manufacturers.

Speaking of Jurado, Citlalli’s photo, a 15-second exposure in France, comes from a series titled Esto no es un unicornio (This is not a unicorn), a reference to the book I just mentioned. It reminds me of Paul Caponigro’s Running White Deer, which is one of my favourite photographs.

More of Citlalli’s work: Website | Facebook

Diego’s X-Ray Peyka

But why stick to conventional film when you can use X-ray film? Diego Cúneo (Buenos Aires, Argentina) is “Divulgador de la F.E.” (Preacher of the Faith) at El Mundo de Peyka, a social and educational project whose purpose is to promote pinhole photography. The website has some great resources, including a free template and instructions to build the cardboard Peyka camera. Diego’s camera is a Peyka (of course) and his photo was a 2-minute exposure at home, using X-ray film. I love the low angle – a “child’s eye view” of the soft toy. And the glow, as of nostalgia or memory.

More of Diego’s work: Instagram

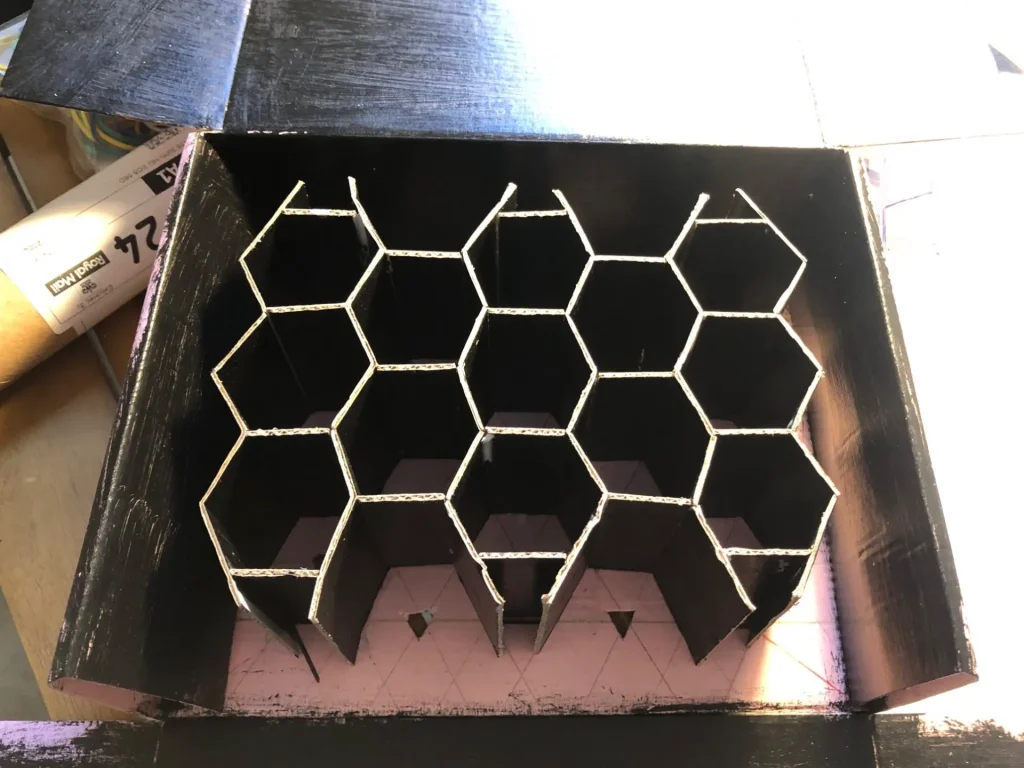

Jim’s Hex-Cam

Cameras with one hole are so mainstream. Jim Anning (Reading, UK) created a cardboard “hex-cam” with 17 pinholes. The partitions limit what the paper “sees”, so the pinhole images don’t overlap. The camera has a cardboard shutter, which is removed to expose the 17 pinholes simultaneously.

His kaleidoscopic self-portrait was a 30-second exposure in bright sunlight, on 5×7″ Ilford MGRC paper. The paper was developed in mint-ol, which is basically caffenol but with mint tea instead of coffee. I’ve never tried it myself, but Jim explained that fresh mint contains caffeic acid which is the main reducing agent, smells nicer and is better for developing paper because unlike coffee, you can see through it.

The pinholes were drilled in beer-can aluminium. Jim aimed for a diameter of around 0.3 mm (four times the width of a human hair), for an aperture of around f/230. He tried to make them all the same size, but from the photo you can see that there’s some variation. I quite like the effect though (automatic bracketing), as well as the slightly different perspectives caused by parallax.

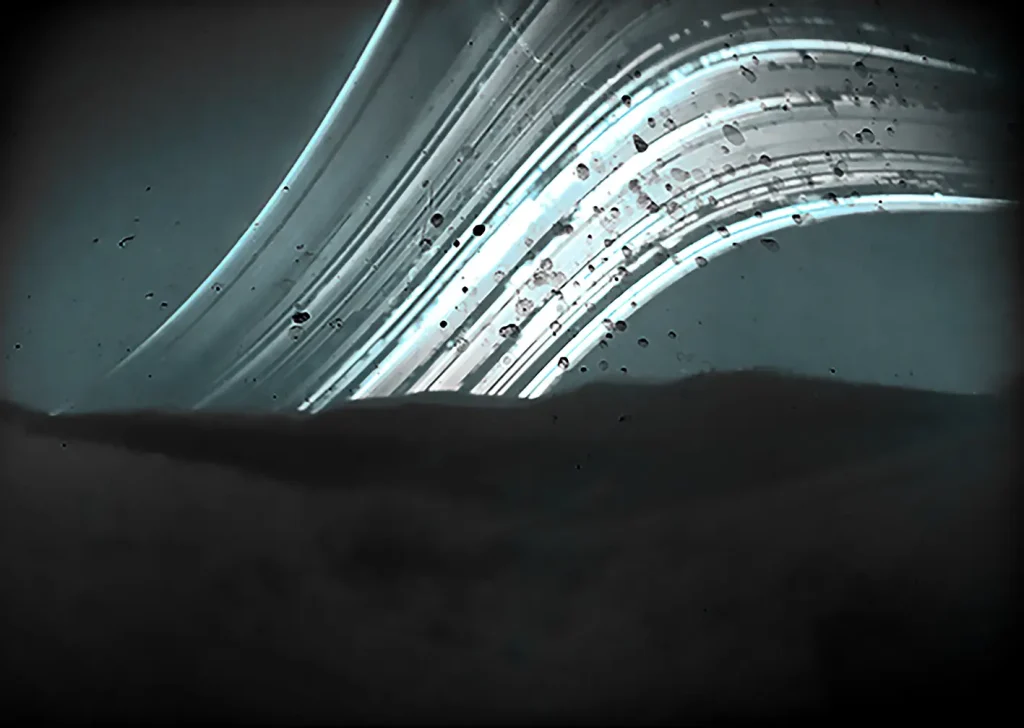

Olga’s Beercan Suntracer

If exposure times on the order of minutes seem long, try months. Olga Suchanova (London, UK) used a pinhole camera made from a beercan – and not just any beercan, but a Peter Saville design for the Tate Modern – to record the solargraph below.

She used Ilford paper, exposed for 3 or 4 months at an art residency in Almeria, Spain. The long exposure traces the sun’s path across the sky over multiple days – sunny days make brighter lines, and as spring turns to summer, the sun rises higher in the sky. The fantastic colours – another consequence of the long exposure – are created spontaneously on black and white paper, without the need for development or any other chemical processing.

This image was shortlisted for the 2020 Astronomy Photographer of the Year Award, and will be exhibited at the National Maritime Museum in London from October. You can also see it, along with the other shortlisted and prizewinning images, in this video.

What I love about it is that most astronomy photographs are taken with highly sophisticated, expensive equipment – powerful telescopes, cooled sensors, equatorial tracking mounts. Olga’s image was made with a recycled beercan.

More of Olga’s work: Instagram

Jeff and Diana’s Sun-Can Exchange

Like Olga, Jeff McConnell (New Jersey, USA) and Diana Pankova (Minsk, Belarus) also make solargraphs on photo paper. Each had been making and using pinhole cameras for some years, and when they were both included in an exhibition in Heidelberg in 2019, they met there and decided to collaborate. For their CrossWorlds project, they have been mailing cameras, or sometimes just exposed papers, back and forth, creating spectacular double exposures. Different landscapes, same sun. Or as Jeff puts it, “Sun collected across some distance, distilled, mixed.”

The photo below was exposed for two weeks in two different places: New Jersey and Minsk. It was recently exhibited at the Pavlovka Pinhole Festival in Kiev.

More of Jeff’s work: Website | Instagram

More of Diana’s work: Instagram

María Luisa’s Pistachio-Cam

María Luisa Santos Cuéllar (Oaxaca, Mexico) has been making and photographing with pinhole cameras for 15 years, and along with Citlalli González (also featured in this post), has been running the Oaxaca Estenopeica pinhole festival since 2009. She showed me a veritable museum of homemade cameras made from containers of various shapes, sizes and materials. And then mentioned, almost in passing, that she made one from a pistachio nut.

“Wait, what? A pistachio nut?”

“jajaja yes pistachio nut.” Followed by the immortal words, “You can make a pinhole with almost anything.”

Here is María Luisa’s pistachio-cam self-portrait, a 3-minute exposure on photo paper. I later learned that she made a camera from an orange, but by then I was past surprise.

More of María Luisa’s work: Instagram | Twitter (Oaxaca Estenopeica) | Instagram (workshop)

Resources

These are lots of pinhole resources online, but I’m listing the ones which I found most useful, for anyone who wants to explore the topic in greater depth (and partly for my own future reference!) If you know any other good resources, please let me know in the comments.

Jon Grepstad has an in-depth page covering the history, science and construction of pinhole cameras. Picto Benelux has a similar page, plus DIY tips and a truly amazing gallery of wooden cameras by René Smets. A smaller, simpler camera for 35mm film can be made from a matchbox, which I want to try someday (obviously!) Nick Dvoracek’s Pinholica blog has more advanced camera designs (different film formats, variable focal lengths, view-camera-style rising fronts, you name it) and an archive of historical articles.

There several sites which help calculate optimum pinhole diameter, angle of view and other parameters. Anecdotally, MrPinhole seems to be the most popular, but for reasons which I’ll explain in a later post, I prefer Chris Patton’s calculators. For the non-technically-inclined, simple trial-and-error also works.

Of the more community-centric resources, there’s f295 forum, and the Facebook pinhole group where the idea for this post was born. I already mentioned the Lensless Podcast; their guests include artists, camera makers and art professors, talking about work, gear and philosophy. I’ve also mentioned Peyka’s cardboard camera template, but they also have a gallery of beautiful homemade cameras, and free issues of Stenopeyko magazine (in Spanish, but I use Google Translate). I won’t list individual photographers as there are so many who are producing wonderful work, but New Mexico Digital Collections and the Worldwide Pinhole Photography Day website both have online galleries with several thousand pinhole images from all over the world.

The best resource I’ve found, however, is a book, Pinhole Photography by Eric Renner, one of the leading lights of the pinhole renaissance of the last few decades. After reading his book this summer, I googled his name wishing to thank him, and discovered to my sadness that he had passed away just a few days earlier.

Thanks, and watch this space!

I’d like to end with a huge vote of thanks to the photographers and camera-makers who are featured in this post, for letting me share their images and answering all my questions. More generally, I’m grateful to everyone – including the authors of the resources listed above – whose knowledge, skills and photography have helped me in my nascent pinhole journey.

You can follow that journey, if you wish, in my next post where I’ll talk about building and shooting with my own homemade camera, and – if Hamish continues to indulge me – in future posts where I’ll talk about other experiments, successes and failures. You can also check out my Instagram which is mostly “lens photography” (as pinhole photographers call it) and darkroom-related content, but I am starting to feature pinhole photos too. Lastly, if you have any questions or comments about the cameras featured in this post, I’ll be happy to pass them on to the people who made them. Thanks for reading!

Share this post:

Comments

Juan Suarez on Nine Homemade Cameras: Pinhole Adventures Part 1 – by Sroyon

Comment posted: 21/09/2020

Comment posted: 21/09/2020

Bob Janes on Nine Homemade Cameras: Pinhole Adventures Part 1 – by Sroyon

Comment posted: 21/09/2020

Comment posted: 21/09/2020

Stephen J on Nine Homemade Cameras: Pinhole Adventures Part 1 – by Sroyon

Comment posted: 21/09/2020

I have been messin' with pinholes for a good few years now and until today was unaware of some of the resources that you have included, thanks too for this.

Finally, I have been fiddling about with my scanning process, and have "graduated" from something that worked well but was slow, to something which is meant to be quicker, but so far is completely unviable. As a result, I have been questioning my use of film, I have a lensed camera which operates in the very same way as a film camera (Leica M-D), and I am now questioning whether I want to use film cameras at all, apart from pinholes of course.

By reducing my film output and instead concentrating on film purely for artistic (some hope) creation, I can make it more meaningful, and have more fun and less frustration along the way.

I think I will start with a Peyka!

Comment posted: 21/09/2020

Rock on Nine Homemade Cameras: Pinhole Adventures Part 1 – by Sroyon

Comment posted: 21/09/2020

Comment posted: 21/09/2020

Scott Gitlin on Nine Homemade Cameras: Pinhole Adventures Part 1 – by Sroyon

Comment posted: 21/09/2020

Comment posted: 21/09/2020

BG on Nine Homemade Cameras: Pinhole Adventures Part 1 – by Sroyon

Comment posted: 21/09/2020

I love your ideas and enthusiasm in your posts, Sroyon. Glad you're here! :)

I'm looking forward to Part 2.

Comment posted: 21/09/2020

Comment posted: 21/09/2020

Winners of the 2020 Astronomy Photographer of the Year Contest - MetInfo on Nine Homemade Cameras: Pinhole Adventures Part 1 – by Sroyon

Comment posted: 22/09/2020

Alexander Seidler on Nine Homemade Cameras: Pinhole Adventures Part 1 – by Sroyon

Comment posted: 22/09/2020

Also seen at... - Allysse Riordan on Nine Homemade Cameras: Pinhole Adventures Part 1 – by Sroyon

Comment posted: 24/02/2022