I wrote an article in 2001 about an almost 100 year old camera. Revisiting it now just over 20 years later I am staggered at the progress that has been made with digital equipment in such a relatively short time. It has had a similar impact to what happened when the Leica 1 came on the scene in the 1925 and larger formats were gradually nudged aside by 35mm in many fields. But for that to play out it would take 40 or more years before the SLR really cemented 35mm’s hold on the market and another 20 or more before the last iterations of film cameras gained so much automated sophistication.

My closing paragraph could not have been further off the mark also. The Olympus C2000 I was using then now resides in a cupboard as a reminder of the progress that has been made. So here is the story again as written for a 2001 reader:-

Bringing a 19o6 camera back to life

In basic terms, I bet there would not be a deal of difference between the steps today’s novice photographer takes to improve their results as compared to what would have happened around a hundred years ago. Nowadays as then, interest in photography usually starts with a simple camera with no controls to speak of and total reliance on trade processing, usually leading to mounting frustration with the results. The main difference in 2001, however, would be that the newcomer to photography is much more likely to input his images into a computer for output to an inkjet printer rather than spending hours in the dark, being exposed to all kinds of health hazards.

One of the first items of equipment that falls short of expectations is usually the camera itself. When you want to take a step up nowadays, there is a whole bunch of options, ranging from the so-called “bridge” cameras, like the Olympus IS range, to a gaggle of “entry level” SLRs to tempt you, plus the increasing number of very capable consumer digital camera offerings. These comprehensive performers offer something with a lot more control and flexibility, but in a fairly compact and lightweight package.

So what would have been on offer if you had lived at the turn of the last century, in 1901 not 2001? What would someone in a similar position a hundred years ago have had available?

The late Victorian would probably start out with a very simple box camera, one of those “You press the button, we do the rest” gadgets. Unfortunately, those cameras required you to make as many as a hundred exposures before you could send the whole camera away to have the film processed and printed, to be returned to you some time later, along with a fresh load of film. The number of exposures was reduced over time but when the photography bug really bites, patience is not something that accompanies it, and the urgency to see results increases in direct proportion to the enthusiasm involved. Having to finish 24 or 36 exposures can be bad enough today when you know that there is that absolute masterpiece in there, but with another 97 to go it must have been unbearable.

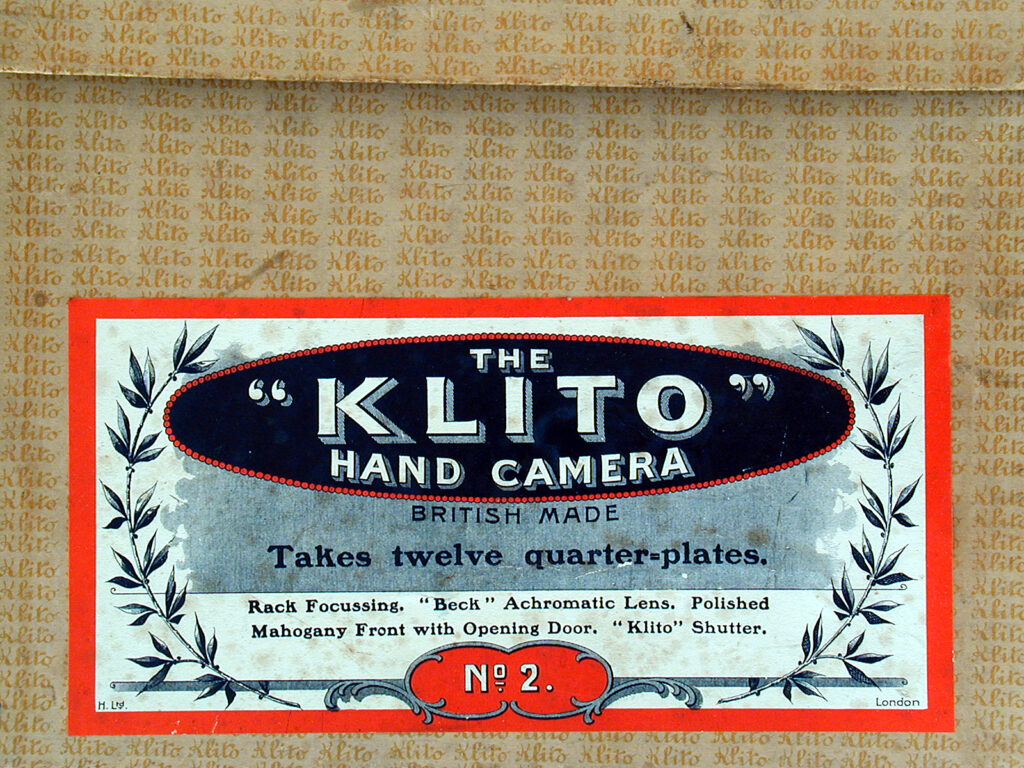

The Klito no. 2 hand camera

These thoughts came to mind when I came across what must have been the equivalent of these “second rung of the ladder” cameras, but one dating from around 1906. I found it in a little bric-a-brac store in Dunedin, New Zealand on the last day of a trip to visit my daughter who lives there in 1999. It took the form of a Houghton’s Klito No. 2 Hand Camera, in its original box and with a complement of quarter plate film holders. It also bears the logo of the original supplier, namely Sharland and Co. Ltd, Photographic Dealers, Wellington NZ, no longer trading unfortunately.

The Klito range was made by Houghton’s Ltd of London, England, the firm eventually becoming Ross Ensign after several mergers over the years between the two World Wars and just afterwards. The Klitos catered for a range of ability and interest coming in several versions with varying specifications and is what the “Primus Handbook of Photography for Novices” published in 1902 describes as a “Reservoir Hand Camera”. The adverts in this fascinating little book include almost twenty different models of these cameras from several manufacturers, also giving the opinion that they are “capital instruments as constructed these days” so they were clearly a very popular type.

Having brought the camera half way round the world, I thought it would be a good project to try to make some images with it to explore its capabilities and to find out what it offered its original owner. I must say, the experience contrasted sharply with the spontaneous style of modern-day photography.

Specification

The box proclaims it offers such desirable features as: Rack Focussing, “Beck” Achromatic Lens, Polished Mahogany Front with Opening Door and Klito Shutter. The only thing not working was the shutter, which had received some uninformed attention at some time but which is now functioning once more after its simple actuating springs were straightened and returned to their intended locations. Everything else works, if a little stiffly.

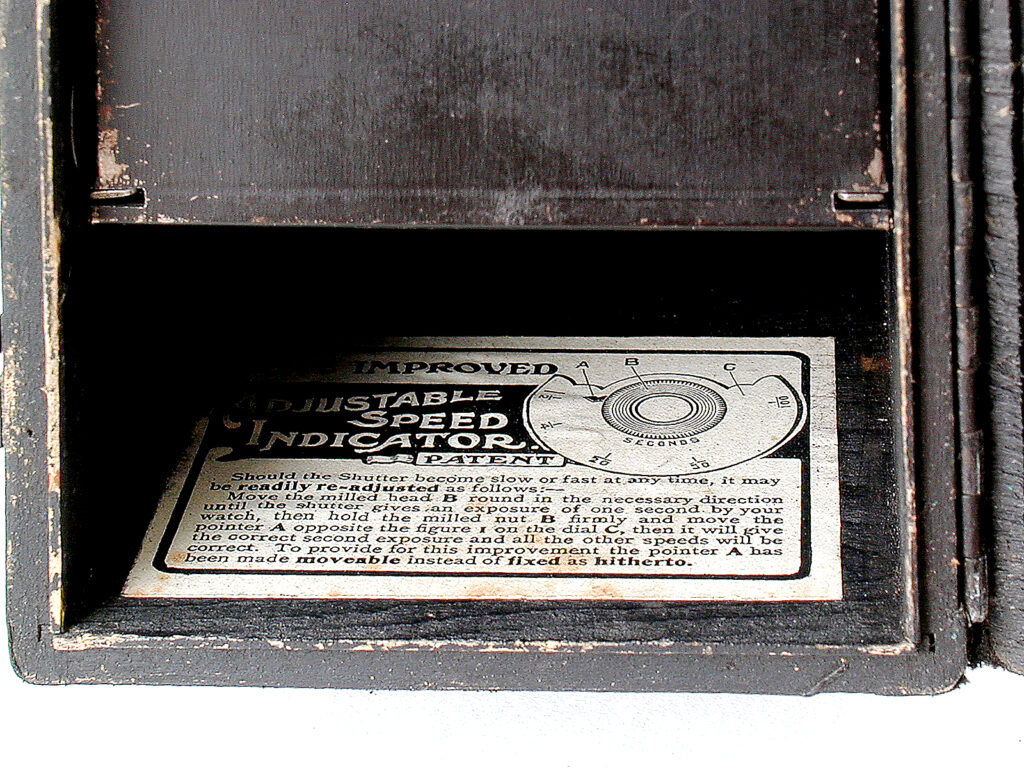

Shutter

Shutter speeds of 1/100, 1/50, 1/25, 1/4, 1/2, 1 and 2 seconds are marked on the speed dial and long time, T, set with a lever on the camera front panel. The shutter needs a few “warm-up” releases before the speed settings settle down, but a brass rod which pulls up a sliding blind behind the lens protects the film chamber and allows these dummy exposures to take place safely. Because the timing is controlled, if that is the right word, by the friction between two paper discs, varied by spring pressure applied through the speed setting knob, intermediate settings are also possible but not calibrated.

Before use, the whole thing has to be set up, the 1 or 2 second speed settings being guessable enough for this initial calibration. This is achieved by moving an adjustable stop concentric with the speed dial and making blank exposures (with the sliding blind mentioned above in place) until the opening time is around one or two elephants long. A real finger nail breaker this one, though, as ergonomics is not a strong point of the camera’s design.

Focus

Focussing is by rack and pinion activation against an engraved scale, with a set of bellows enclosed within the boxy body and only visible when the focus rack is extended from the infinity position. The movement extends the whole of the front section carrying the lens, iris and shutter forward to focus down to a little under a marked 3 feet. The bellows are in pristine condition, doubtless due to being hidden away from light and other undesirable effects of the atmosphere.

Aperture

The aperture is constructed of nine blades, which produce a very smooth, circular opening, and is mounted in front of the lens. It offers continuously variable stops marked at f/11, f/16, f/22 and f/32.

Focus, shutter speed and aperture adjustment would all benefit from the application of graphic and ergonomic design, needing very close inspection and strong fingers and nails to adjust them.

Lens

The lens fitted is of two element construction, made by Beck, and is of good quality, producing very sharp results. It is buried inside the body, behind the iris and shutter so that despite lacking any form of coating it shows surprisingly good contrast. It also has a maximum aperture of f/11, which, when combined with the range of shutter speeds available, means that subjects can be taken in full sunlight hand-held with a modern ISO125 speed film. In good light, an exposure of 1/50th or 1/100th sec at f/11 on the film of the day would have been possible hand-held but depth of field would be shallow and focus estimation critical. Other subjects in less strong light could be tackled, provided a tripod was used. Tripod sockets for the purpose are provided on both the base and one side so that the photographer retains the options of landscape and portrait formats.

Viewfinder

Viewfinders are also provided for both formats, but are small and difficult to use. Results also suggest that their accuracy leaves a little bit to be desired but no doubt manufacturing tolerances would not be all that tight and over the 90 years of its life, the camera may well have suffered a few knocks to disturb their alignment. I therefore avoided framing too tightly and I am sure that even in its day, this feature alone would have been sufficient reason for the proud owner to eventually convince themselves that they just had to have a stand camera with a focusing back to do justice to their work.

Film holders

The 4 1/4” x 3 1/4” sheet film used by the camera is carried in holders, purpose made to be loaded through a door in the back, fitting onto two tracks along each side of the camera body. Up to 24 holders can be loaded, stacked against a stop in the focal plane by a large spring fixed to the door in the back of the camera. Once an exposure has been made, a knob on the top of the camera is slid sideways, allowing the freshly exposed film holder to be pushed forwards and to fall face down into the base of the body. A second, smaller door just below the film loading door then allows holders to be removed in the darkroom at any time without disturbing the unexposed holders and without having to wait for all the available exposures to be made.

The fiddly catches on these doors require quite a bit of dexterity to operate but are certainly guaranteed to protect the exposed emulsion from accidental fogging. I was unable to locate any film of the necessary size to fit and so had to cut down 5×4 FP4 to size.

In use

Once attached to a sturdy tripod, the trials of the viewfinders really become apparent. The camera can really only be used no higher than chest high and then with some difficulty. The viewfinder optics are definitely designed to be used at waist level to be able to see the subject reasonably accurately. The original high eyepoint viewfinder perhaps.

The highest shutter speed does allow hand holding once the rather stiff release is mastered. At slower speeds some further practice is needed because the shutter is self-cocking and self-capping. This means that the release has to be held at the end of its travel to prevent it returning to the ready position prematurely thus capping the shutter and cutting the exposure short. A latch position is provided at the end of the lever’s travel to prevent this and, once the knack is acquired, is a very effective aid.

As the results show, the camera is capable of some very fine images with creditable contrast and sharpness.

On reflection

The images were produced on Ilford FP4 sheet film and processed in diluted Agfa Rodinal developer. The resultant negatives were scanned on an Epson flatbed scanner with a transparency lid and corrected for geometry and tonal balance in Photoshop on an AppleMac computer. I then output the results onto CD-ROM and inkjet prints.

It seems very strange making the exposures with equipment and technology which was around at the beginning of the last century and then making the positives digitally on modern computer equipment. The developer in a way bridges the intervening years, having been introduced in the 1890’s, and therefore available when this camera was new.

I suppose that therein lies the moral to this tale, if there is one. I have been using equipment from the early days of photography along with chemicals formulated in the same era and basic monochrome materials to make an image on film in the camera. By contrast, I then used modern computer imaging systems to output them to a slim, shiny disk of plastic to send by mail to an editor for consideration, in a way that would seem to be almost unbelievable to that late Victorian photographer who first owned and used the Klito.

It has made me realise that, despite photography in all its facets having come so far, not all that much has basically changed. To be sure it is easier to get an image onto film or into a computer, the illustrations of the Klito in this article are shot on an Olympus Camedia C2000 digital camera and downloaded to computer via a card reader in seconds, nevertheless the basic objective of creating a satisfying image remains the same and takes just as much creative effort at the end of the day. It is much easier on the eyesight and finger nails, though.

You never know, someone will maybe find my digital Olympus in a 2090’s equivalent of that bric-a-brac store in Dunedin and try to produce images from it as well. I wonder.

Final thoughts today in 2024

As I said at the beginning, I couldn’t have been more wrong with my final remark. For example, 20 years on from its 1925 introduction only saw the Leica progress from the fixed lens model 1 to the model 111f, still essentially the same camera but with a coupled rangefinder and interchangeable lens. I now use a, rather dated, 20 megapixel mirrorless camera introduced in 2013 and most of my work is viewed on a computer screen, not printed out. In 20 years the camera has moved on more than 10 times in average output size and worlds more in what it can do. And don’t get started on the mobile phone!

Share this post:

Comments

Arthur Gottschalk on Klito no. 2 hand camera – That time when I revived a camera from 1906.

Comment posted: 22/01/2024

Comment posted: 22/01/2024

Brad Davis on Klito no. 2 hand camera – That time when I revived a camera from 1906.

Comment posted: 22/01/2024

Comment posted: 22/01/2024

Jared Gerlach on Klito no. 2 hand camera – That time when I revived a camera from 1906.

Comment posted: 22/01/2024

Steviemac on Klito no. 2 hand camera – That time when I revived a camera from 1906.

Comment posted: 22/01/2024

Comment posted: 22/01/2024

Gary Smith on Klito no. 2 hand camera – That time when I revived a camera from 1906.

Comment posted: 22/01/2024

The presented results look great!

Julian Tanase on Klito no. 2 hand camera – That time when I revived a camera from 1906.

Comment posted: 23/01/2024

Comment posted: 23/01/2024

Geoff Chaplin on Klito no. 2 hand camera – That time when I revived a camera from 1906.

Comment posted: 23/01/2024

While reading the article I imagined myself cutting ortho film under a red light but you used fp4! Presumably you made some form of template and then worked in darkness. Success rate?

Lance Rowley on Klito no. 2 hand camera – That time when I revived a camera from 1906.

Comment posted: 24/01/2024

Comment posted: 24/01/2024

Eric on Klito no. 2 hand camera – That time when I revived a camera from 1906.

Comment posted: 28/01/2024

Wonderful article and images. Truly inspiring. Impressed with the product pics taken with the Olympus C2000 also. Thank you for sharing.

Eric

Scott Gitlin on Klito no. 2 hand camera – That time when I revived a camera from 1906.

Comment posted: 01/02/2024

Comment posted: 01/02/2024