Large format has constantly fascinated me ever since I became seriously involved in photography many decades ago. The fact that it is possible to adjust the image to produce a more convincing rendering of the subject fascinated me, especially in the area of architecture, my own profession.

Over the years I have tried to involve myself when I could with these formats as much as was practical in order to learn as much as possible along the way, but very much on an amateur basis. It is only recently that I could afford to experience a camera with full movements. It has progressed in three basic stages each followed by a period when I made use of what I had discovered before moving on.

I progressed from a basic pinhole camera to precision instruments, my first steps covered in my post about using Multigrade as film, and progressed by way of a falling plate camera of the 1900s you can find here and a Zeiss Ideal from the 1930s here.

This, the final stage, took me into “real” large format with a couple of technical cameras with movements and some quality glass.

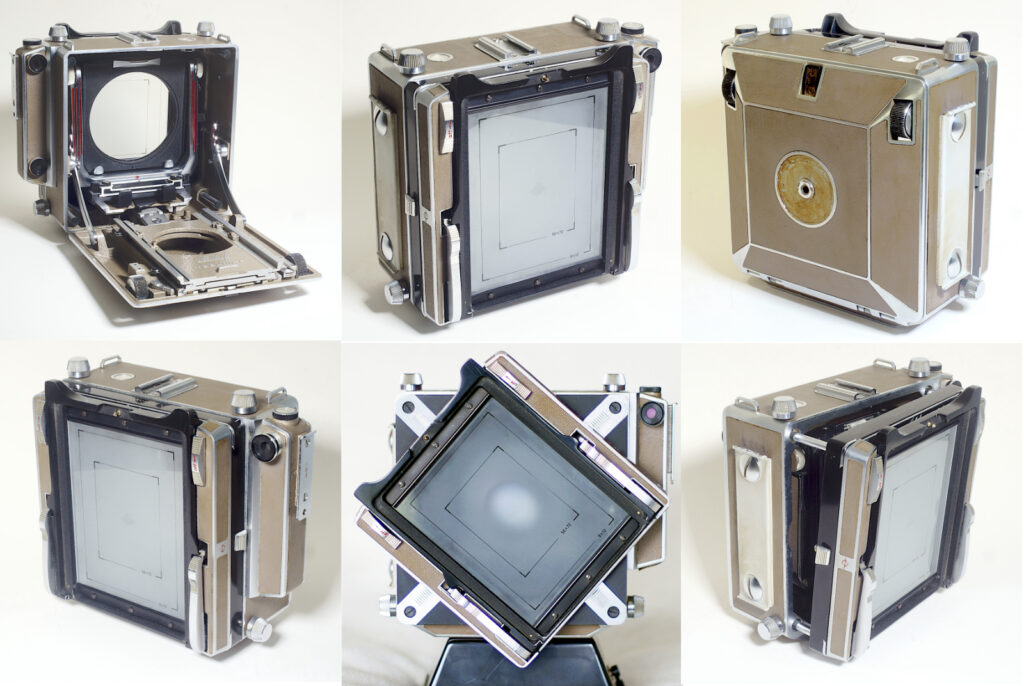

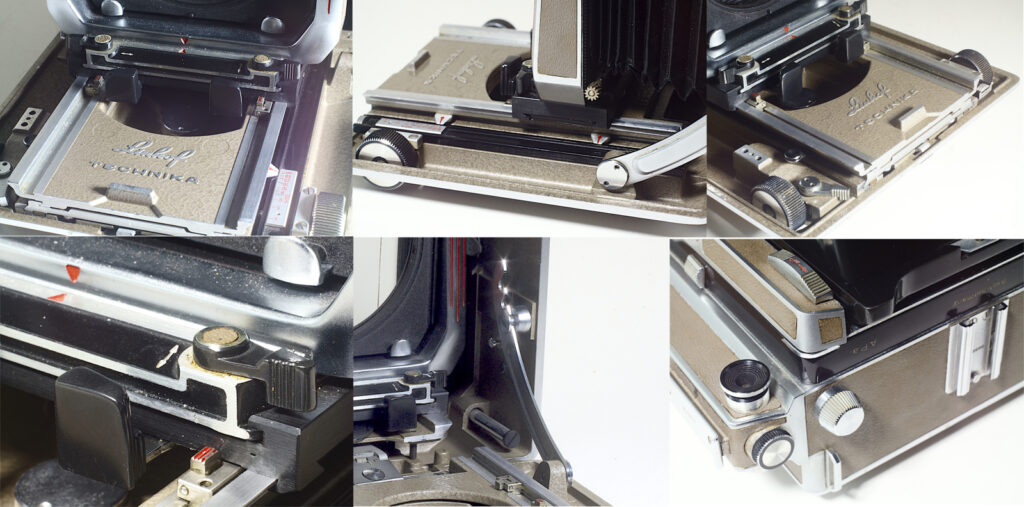

The Linhof Super Technika IV

I came across an example of this top flight camera, complete with two lenses, just across town from me. The seller had had no success selling it on line until I turned up. Possibly a portent of something to come.

The full range of movements that came with the Linhof Super Technika IV with two Schneider Lenses, 90mm and 150mm was an absolute revelation. It is a quality, precision technical camera with precise movements, manufactured around 1960 from the highest quality materials and the result of a long series of metal bodied models, each one improving upon the previous incarnation. This model was the basis for still later improvements over a total of around 40 years in all from the mid 1930s to the late 1970s. A choice of accessories was produced to allow it to be used for a range of purposes.

Everything about the Linhof exuded quality. Made from machined metal components manufactured to tight tolerances, everything worked very precisely and smoothly. As I used it over a few years one of the things that gave me problems was its weight. I am no spring chicken and toting the Linhof and its lenses plus a Benbo Mk1 tripod was starting to tell. So I began looking for a replacement which would not weigh me down quite as much. The photographers who used these cameras in their heyday, particularly handheld, must have had strong arms and backs!

The other niggle was using the 90mm wide angle. This required the bed to be dropped to a preset notch, the front standard tilted back to vertical and then moved back quite tightly against the body to a preset stop which severely limited movements.

So after a few years of enjoyable use I began a search to find a lighter replacement

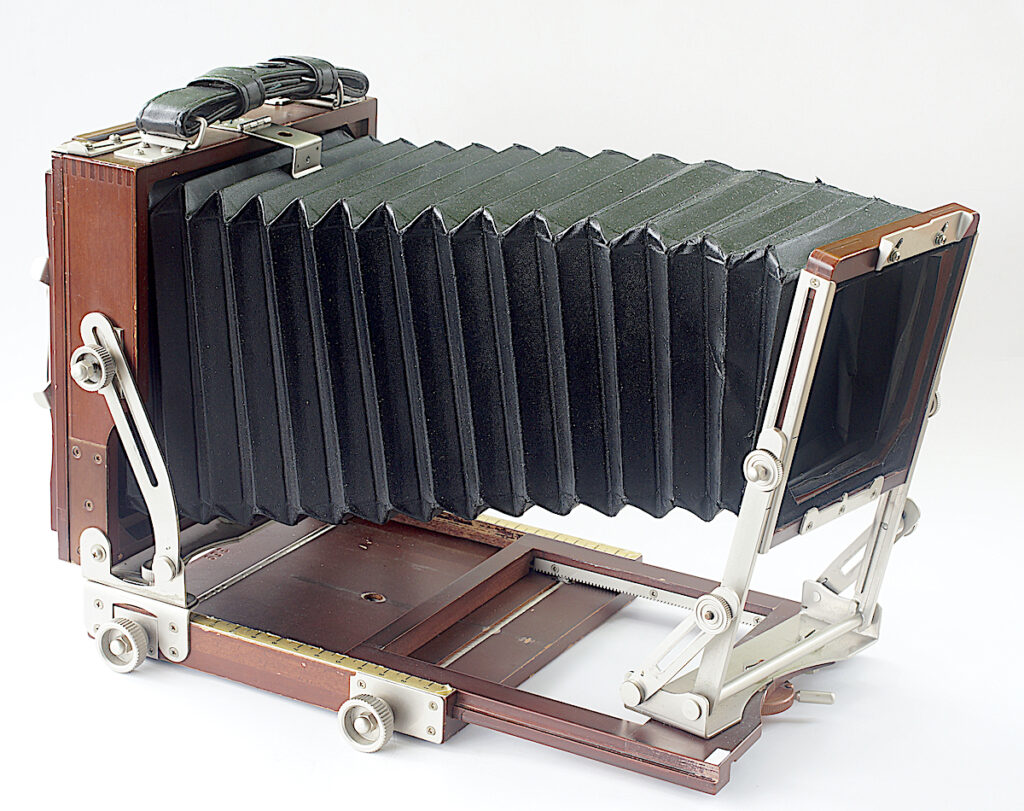

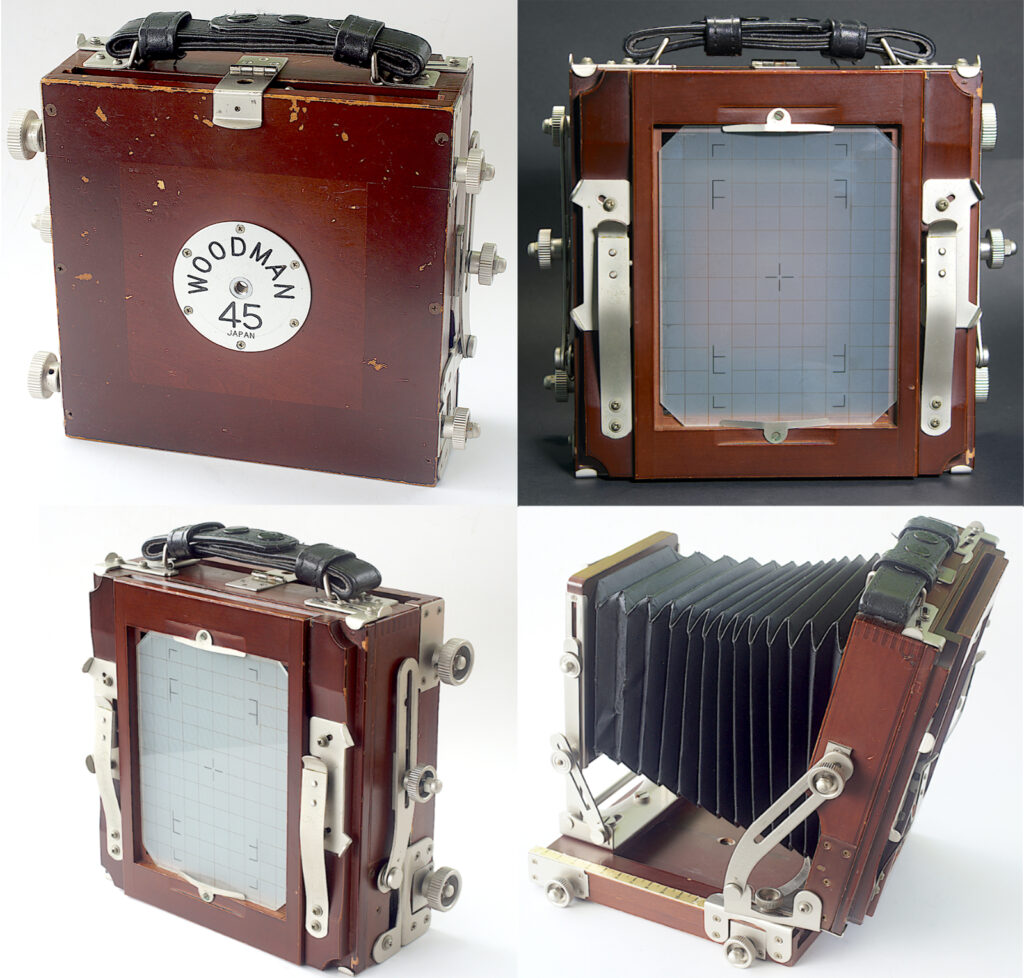

The Komamura Woodman 45

I would have liked to go for a new Intrepid or a used Tachihara or similar but, just like the previous seller, my efforts to sell the Linhof body on the New Zealand equivalent of ebay to fund the new camera came to nought. The only offer I had was in exchange for a Woodman, a make I had heard of but knew little about.

Unfortunately, my initial research into the Woodman was not encouraging to say the least. The general view seemed to be that it was the flimsiest of cameras and not a patch on other makes I could consider. One reviewer, however, gave me a glimmer of hope, suggesting that it all depended on what would be expected of it in use so my more gentle demands should mean it could be adequate for my purposes and both bodies had an equivalent value.

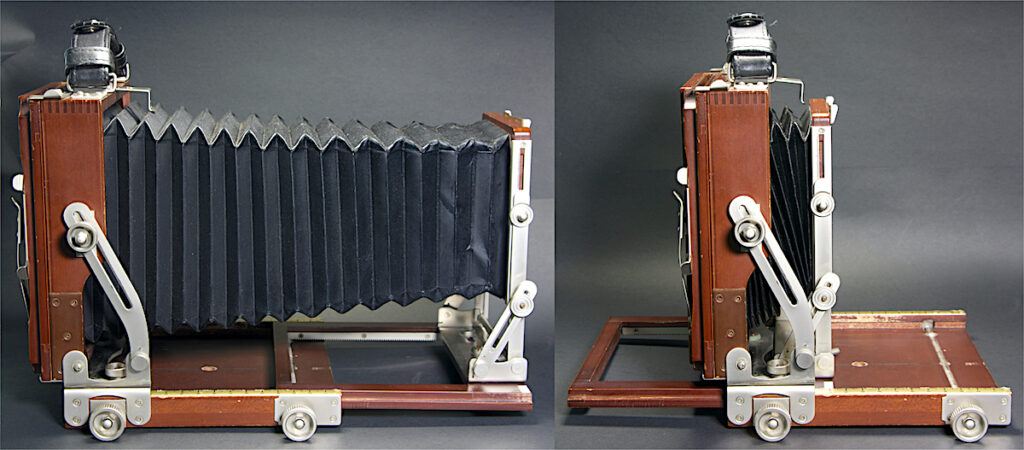

The Woodman was made in the 1990s but could as easily have been made in the 1890s, being the same design as similar models of that time. It is constructed from wood with plated metal fittings to manually control the movements.

The clincher was that the Linhof body weighs 2.7 kilos/6.1 lbs against the Woodman’s 1.45 kilos/3.2 lbs. With lenses etc the Woodman weighs about the same as the Linhof body alone so it was worth considering.

The design had aspects that appealed to me also, not the least being the easier use of a wider angle lens, which I used quite a bit. As mentioned, the Linhof was quite fiddly whilst the Woodman focus rack allows a more forward positioning of the lens so that the drop bed is not necessary though possible if it was appearing in frame when using some front fall and movements generally were not restricted.

Overall, the Woodman is actually much more versatile than it seems.

Being realistic

Essentially though, the Woodman and the Linhof are like chalk and cheese. They couldn’t be more different as my research had shown. But, at the end of the day, manufacturing quality apart, they serve the same basic function, i.e. to hold a lens/shutter unit and a light sensitive material precisely relative to one another within a light-tight container in order to produce a focused image, the function of any camera.

Despite the step back in build quality terms, what finally convinced me was the fact that both use the same lenses and lens board, standard double dark slide film holders, are much the same size to fit my Pelican-type case and offer a similar range of movements.

And the proof of the pudding is in the eating as they say and the results are equally good, since they depend solely on the lens and the emulsion after all. Other factors will only affect the handling of the camera in practical terms.

The ravages of time

Now well into my eighties, I had to reluctantly accept that 5×4 is just too physically demanding for me these days and I sold everything on and focussed my attention at the extreme, opposite end of the format spectrum, 16mm, as you may have seen elsewhere here. Weight is no longer a problem.

Finally

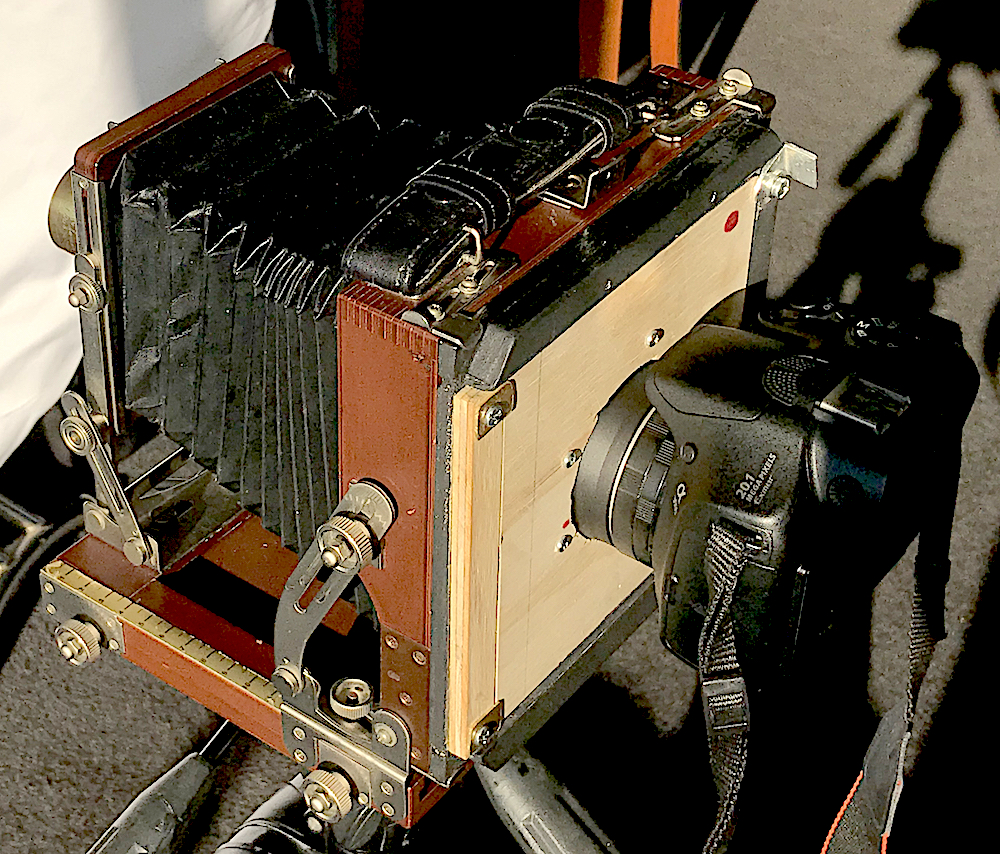

There is something very satisfying about making an image with a large format camera. Rather like the mirrorless digitals, almost any lens can be used. My own modest selection started in 1903 and ended around 1960. DIY is fairy uncomplicated, the brass Robinson lens for example was mounted on a lens board “manufactured” from a sheet of aluminium using only a drill, a hacksaw and a file. I even made a back for my mirrorless digital and combined multiple frames for a larger image using the front movements to cover the required image area and merging the images to produce around 50 to 100 megapixel files.

My Sony A3000 body mounted on the back panel and fitted to the Woodman.

A 46mb image produced with the digiback and merged from 9 images.

100 years separate the arrival of the lens and the model into the world – 1903/2003. The Robinson lens was at maximum aperture, approx. f10.

It does requires a great deal more thought and involvement from the photographer, and also from the subject if you decide to tackle portraits for example. But this is all part of the original ritual of photography that has been gradually left behind by advances in camera design over the years and more recently by digital and the mobile phone of course.

If you are tempted to dip a toe into the large format pool there are many ways to explore it from pinhole to full on technical.

Two books that I have constantly referred to and provide a great deal of technical information are:-

View Camera Technique by Leslie Stroebel (ISBN 0-240-51711-3) and Using the View Camera by Steve Simmons (ISBN 0-8174-6353-4)

They may be hard to find these days but there is plenty of information on the web which can be picked through for quite a lot of useful material. One exceptionally useful site can be found at largeformatphotography.info

Share this post:

Comments

Bob Janes on A Final Chapter for Large Format

Comment posted: 23/02/2025

Daniel Emerson on A Final Chapter for Large Format

Comment posted: 23/02/2025

Yes, 4x5, Linhof, Woodman, someone pushing the bounds, a quick check of the name, Tony Warren ... not surprised at all.:) Stunning shot of the pocket watch with the Linhof. How did you light it?

regards

Daniel