As it turned out, the Bremen ports are a real playground for photographing industrial architecture. The place offers proud warehouses and grain silos coming from glorious past. In this article, I will show you images that are more than two years old. Although I pretty much like them, I have been keeping these photographs hidden in a “poison cabinet” – until now. How could that happen? I am going to tell you in a moment.

The Part About Industrial Architecture

Architecture has always been one of my favorite fields in my photographic pursuits. Especially during the winter half year, the days can be fertile. For my usual approach, I strongly prefer a flat and overcast sky that results in a homogeneous illumination, almost without shadows. Recently, I also enjoyed the mystical nature of the night.

Among the architectural subjects, I find industrial buildings and structures the most exciting. When I first delved into the works of the “old masters”, it didn’t take long until I stumbled across the Becher couple. Their sober black and white photographs of industrial structures, often arranged in standardized grids – wow! Later, I discovered that the Bechers also taught photography at the university and that their students created great art, too.

There is another artist who consistently inspires me: Gerrit Engel. The Berlin-based photographer started his career with a series about the large grain elevators in Buffalo, NY. As much as I would like to explore these industrial dinosaurs myself – 6,000 kilometers distance is a big deal, unfortunately.

The Part About the Location

As my birthday present in 2017, my girlfriend invited me to spend a weekend in city of Bremen (the home of Beck’s beer). We arrived on Friday afternoon and took a guided tour through the Mercedes Benz plant. An interesting place, but – you might have guessed it – no cameras allowed. For the Saturday, we planned to visit one of the several ports. The day started with sunshine, but around noon, a thin cloud layer covered the sky – perfect conditions, exactly to my liking. Oh boy, I couldn’t wait to arrive at the scene. Even today, I vividly remember sitting in the bus, checking my watch. Then checking the sky. Checking my watch again. And checking the sky…

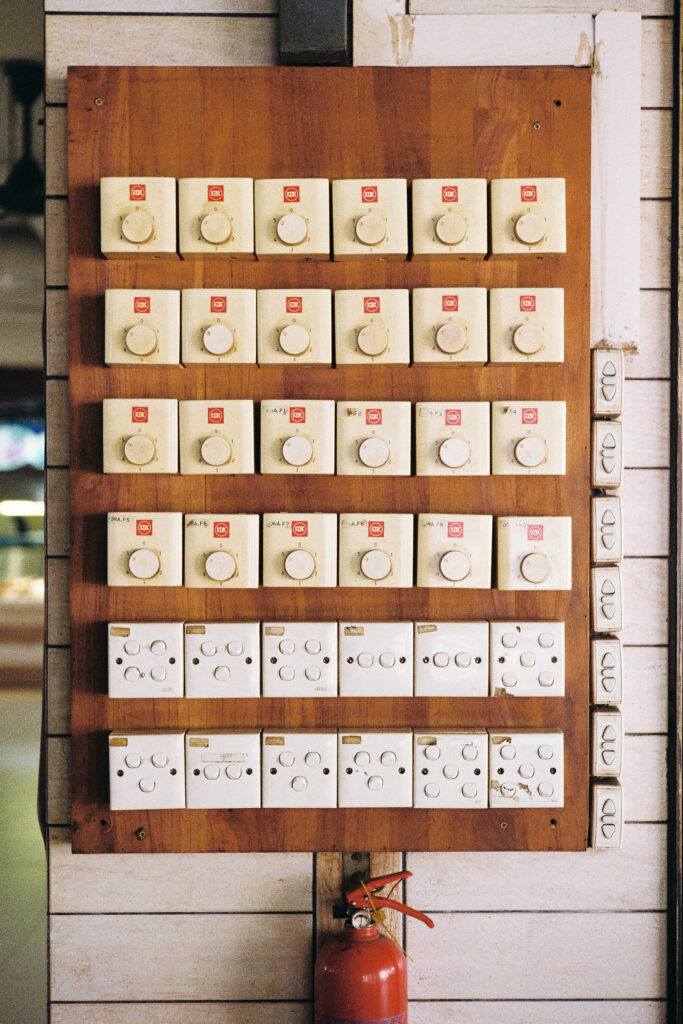

I took all images during this one afternoon at the “Holz- und Fabrikenhafen” (= wood and factories harbor), home to some grain mills and a producer of marine proteins. At this area of the Bremen ports, industrial architecture ranges from warehouses, factory halls and silos to fuel depots, conveyor belts and loading cranes. In former times, Café HAG – the world’s first decaf maker – also operated production facilities at this very basin. In the course of structural transformations, the port’s importance steadily declined. Companies moved elsewhere or even went out of business. This means, many of the facilities aren’t in a good shape anymore.

Having all Options

From a photographer’s perspective, the port was almost heaven. I didn’t encounter any (hindering) fences or walls and I unsuccessfully looked out for no-trespassing signs. It seemed that on the weekend nobody wants to spend his time there. I hardly ever met another soul and not a single car was parked in front of an interesting object. Some of these storehouses are huge. No problem! In contrast to the crammed city center, I easily found unobstructed spots from where the whole building fit into the frame. These circumstances allowed me to shoot the buildings “straight in their face”. Okay, that sounds strange! Let me explain: I mean to parallel align the film plane with the front facade. The resulting photograph resembles a technical drawing – I pretty much like that kind of representation.

The Part About the Gear

For the purpose of architectural photography, I exclusively use a Canon EOS 1N SLR in combination with shift lenses. In Bremen, I had Canon’s two wide-angle options with me, the 17mm and the 24mm TSE lenses. Shift lenses are specialists: They allow you to correct the perspective by shifting their optics up- or downwards (no tilting of the camera necessary to squeeze large objects in the frame). As a result, parallel lines do not converge in the image – they remain parallel. Unfortunately, these lenses only work with SLR cameras as their uncommon design demands a “What You See Is What You Get” approach.

My setup is a rather slow one, requiring a tripod most of the time. Even if the shutter speeds would not end up in the range of 1/30 s and below, a tripod is extremely helpful for precise framing. However, the use of a tripod raises problems in a different department: strangers get suspicious. Especially, when I mount a rather large camera (“Are you a professional?”) on tripod during daytime (“Why do you need that? It’s not dark!”). And they often have no understanding why I am taking photos of such “boring” subjects (“What do you need these pictures for? Who has ordered you?”). Fortunately, as I mentioned earlier, nobody cared at the Bremen ports.

Keeping a Complicated Camera Simple

The Canon EOS 1N offers all the bells and whistles of a modern SLR. Though I prefer a rather minimalist approach, it doesn’t bother me too much. That’s because I stick to a set of settings I had chosen in the beginning: manual exposure mode, manual focus (there are no autofocus shift lenses), f/11, DX readout disabled and mirror lock-up. By the way, the two latter ones are features hidden in the custom functions’ menu. Altogether there are fourteen of these special functions, just labelled from “F-1” to “F14”. Without the manual, you are completely lost in this department. (Interesting comparison: the manual for this Canon fills 118 pages, written in English. The manual for my Plaubel Makina 67 covers 19 pages and combines five different languages.)

The Part About the Material

Kodak Portra 160 is my workhorse. I appreciate its fine grain and the subtle color palette. With a tripod, there is no need for speed, and therefore the rather low ISO is enough. In addition, I discovered a trick to save money with this stock at my local photo store. The store’s staff used a sheet with lots of barcodes on it to determine the price for a given film at the cashier (they didn’t scan the code on the box itself). Fortunately for me, their price information was well outdated – I paid only five Euros when the film was offered for around seven Euros elsewhere. That “method” only worked with the 160 type and with single rolls. (Admittedly, I felt a little bit guilty when buying there. This was surely not the intention of the “support your local dealer” concept. However, who can resist cheap film?)

A couple of weeks after I took the shots at the Bremen ports, I completely switched to black and white film for my architectural photography. To be more specific, I used Fuji Acros 100 exclusively. (Glad this stuff is coming back!) Up to date, I’m not sure which type of representation I prefer – color or black and white. This brings us to Andrew’s well written piece about this timeless dilemma…

The Part About the Winning Team (and the Changing of it)

As mentioned above, I took the images in March 2017. That was three months after I had started to shoot film again. Up to this point, I had sent my films for developing and scanning to a lab 300 kilometers away. The results were very satisfying, but I feared a total loss of my films during shipping. Deutsche Post, formerly the state-run postal service, still enjoys a good reputation for working reliably (in contrast to the German railway company). But you’ll never know… Therefore, I decided to give a local lab a try.

I talked to the staff and showed them some scans from the other lab. They ensured me they could deliver similar results. They could not. The look and feel of the images markedly differed from the ones I was used to. With these local scans, the otherwise grey to white sky turned out blue-ish. They also came out way darker and lacked resolution. Damn, I was disappointed! How stupid: I traveled to a special place, took plenty of photographs of highly exciting subjects under my favorite weather conditions – and then jeopardized the outcome by changing a crucial part of the process.

Several attempts to fix the ill-fated scans in Lightroom failed (In the end, they were kind of ok-ish, but a crack remained. I had screwed up this thing). Of course, my regular lab offered to scan already developed negatives. Due to the extra effort this service comes at an extra price. I wasn’t willing to pay that price, so the scans vanished on the dark side of my hard drive.

The Part About the Happy Ending

Fast forward to June 2019. I had become acquainted with Jens, a film photographer living in the same region like me (and avid author of several articles at emulsive.org). We chatted about different scanning processes and discussed our experiences with different labs. That was the moment when the lost Bremen scans came back to my mind. Following an impulse, I decided to get rid of this “trauma” and ordered my regular lab to scan these negatives again. They came back exactly as I had desired. What can I say? It was worth every penny! The results even encouraged me to write down this story.

The Part with Further Images

As I am writing this piece, I feel the urge to return. There is so much more of industrial architecture at the Bremen ports – I saw only a small fraction of the area during my first visit. Just one kilometer downriver stands the “Getreideverkehrsanlage”, a massive grain silo and loading facility. This building on its own would justify another trip. I am also eager to document the place on black-and-white film.

Thanks for reading!

instagram.com/graindeer

Share this post:

Comments

Jens on Bremen Ports, a Playground for Photographing Industrial Architecture – by Christian Schroeder

Comment posted: 23/08/2019

Hope to see more of your contributions here on 35mmc.

Comment posted: 23/08/2019

Comment posted: 23/08/2019

Comment posted: 23/08/2019

Philip Lewis Lambert on Bremen Ports, a Playground for Photographing Industrial Architecture – by Christian Schroeder

Comment posted: 23/08/2019

Much of my pictures are architectural. I did use perspective control lenses both Nikon and Olympus but now just use photoshop to straighten verticals . I use 15mm , 21mm and 28mm lenses on 24x36mm sensors as the results seem sharper. Film seems a bit exotic now but I am thinking of getting a 120 film slr.

Comment posted: 23/08/2019

Marco Andrés on Bremen Ports, a Playground for Photographing Industrial Architecture – by Christian Schroeder

Comment posted: 23/08/2019

Consider looking at the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher, two highly-regarded conceptual German photographers . The Bechers used exactly that approach to document building types. They made images of buildings on overcast days to emphasize their subject – buildings that were rapidly disappearing. Their books are devoted to a single building type (e.g. Gas Tanks) and to typologies.

At the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, Bernd taught a number of well-regarded photographers: Thomas Struth, Candida Höffer, Thomas Ruff, among others.

The Bechers were just as obsessive as another German photographer – August Sander – who made portraits of archetypes of Germans.

Interesting that you are considering using medium format for your work. The Bechers and Sander used large format for their work, not even cropping. “Go for it”

Comment posted: 23/08/2019

Kevin Allan on Bremen Ports, a Playground for Photographing Industrial Architecture – by Christian Schroeder

Comment posted: 23/08/2019

Comment posted: 23/08/2019

D Evan Bedford on Bremen Ports, a Playground for Photographing Industrial Architecture – by Christian Schroeder

Comment posted: 23/08/2019

Comment posted: 23/08/2019

Huss on Bremen Ports, a Playground for Photographing Industrial Architecture – by Christian Schroeder

Comment posted: 24/08/2019

Comment posted: 24/08/2019

George Appletree on Bremen Ports, a Playground for Photographing Industrial Architecture – by Christian Schroeder

Comment posted: 24/08/2019

Really balanced photographs in the line of the German new objectivity. Great pastel colors and lighting. Excellent

Comment posted: 24/08/2019

Kodachromeguy on Bremen Ports, a Playground for Photographing Industrial Architecture – by Christian Schroeder

Comment posted: 24/08/2019

Comment posted: 24/08/2019

Harry Machold on Bremen Ports, a Playground for Photographing Industrial Architecture – by Christian Schroeder

Comment posted: 24/08/2019

I grew up in that city and at a time, when this was still a very active port by itself; now everything moved up to Bremerhaven at the open North Sea.

I even worked as a student at J.H.Bachmann, who´s premises seem to still exist.

Wonderful shots and dimmed colours, an aesthetical delight to look at. I am working as a vintage camera expert with Leica Classics Camera in Vienna; I always love to study what kind of equipment people are using for their photographs.

Best wishes for your future in Photography!

Comment posted: 24/08/2019

garlo on Bremen Ports, a Playground for Photographing Industrial Architecture – by Christian Schroeder

Comment posted: 24/08/2019

Comment posted: 24/08/2019

Revisiting Bremen Ports – by Christian Schroeder - 35mmc on Bremen Ports, a Playground for Photographing Industrial Architecture – by Christian Schroeder

Comment posted: 19/05/2020