I have been involved in some aspect of photography for forty-five years. I was 15 when I took my first precarious steps attempting to understand the complex simplicity of a pinhole camera reveling in the fluid, time-based aesthetic of light exposing paper. I stepped through the doors of Rochester Institute of Technology at 18 and managed to navigate a myriad of curricula designed to test my resilience as a student of the photographic arts and sciences. Graduate school followed and then a career in academia teaching Film and Photography to where I sit now with one distinct realization.

I love cameras. I mean that I really love them.

And with love comes desire and desire begets acquisition; love follows, more desire, acquisition on a grander scale, and over and over and over. Until you are in a room surrounded by cameras.

Many, many cameras.

Each a measure of passionate “connectiveness” shining from their place on a shelf like a beacon shimmering though the darkest of nights. I walk into my “camera room” and each time I am astounded. The breadth of industrial design, complex machinations detailing the history and nuance of a particular country’s manufacturing processes, and the subtleties of variance and model reformation present themselves with a profound impact.

Scanning the shelves, I am acutely aware that the presence of each camera in my collection is purposeful, a designed inclusion complementing the overall arc of my interests and providing access to a microcosm of photographic design and history. Every camera, regardless of its value or seeming insignificance holds a particular zeitgeist in place, a determination of personal experience or historical reference. As a result, I am inclined to view “The Camera” as discrete, separate, and essentially non-binding when situated within the entirety of “The Photographic Apparatus.”

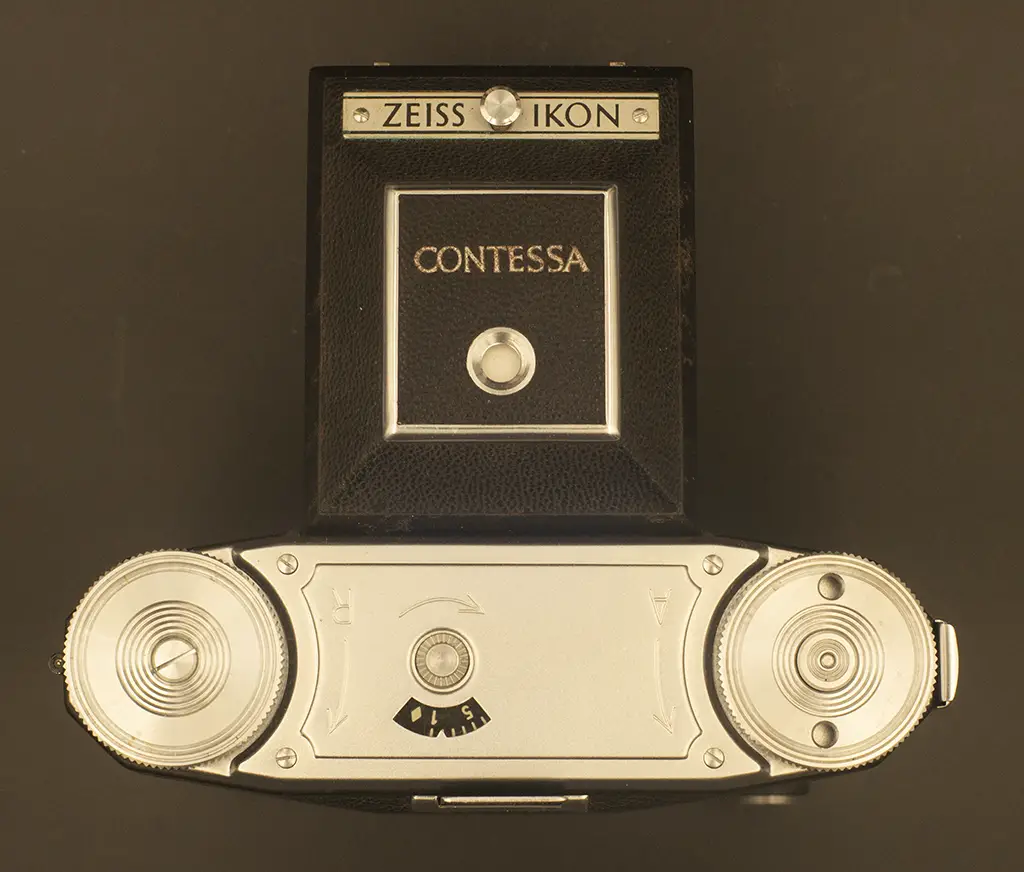

Case Study: The 1953 Zeiss-Ikon Contessa

To “plead my case,” I felt that it was imperative to showcase a camera that presents many of the facets that might draw the attention of a collector. After a careful perusal of my camera room, I decided that the 1953 Zeiss-Ikon Contessa would provide this context. It is, and I’m certain that many would agree, a beautiful example of industrial design, as well as profound iconic significance. In fact, it is difficult to gauge the intrinsic value of this camera’s contribution to the history of photography when aligned with its detailed and comprehensive lineage.

The Contessa is inordinately symmetrical. Rectangular viewfinder mirrors selenium meter. The prominent shutter release spans the top curvature of the 45/2.8 Tessar lens. The rangefinder and its accompanying viewing glass are set directly in the middle of the camera dissecting the accessory shoe perfectly. The familiar Zeiss-Ikon logo is a discrete revelation when the camera is unfolded.

The camera body is appointed with chrome accents, a detail that contrasts nicely with the fine leatherette and the mechanics of the familiar Zeiss Tessar lens are distinct and ergonomically placed. The rewind and film advance knobs are symmetrically placed at the bottom of the camera again reflecting the rigid design. The frame counter appears at the base of the camera so as not to intrude with the well-defined top plate, exposure meter scale and film type reminder. Other appointments reflect a refined user experience.

The tripod socket is integrated into the flip down lens cover and a unique pull-out camera stand affords a robust platform when setting the opened camera on a shelf or table. The heft and construction of the Zeiss-Ikon Contessa is apparent when held in the hand and it suggests a quality of build unmatched in its class.

If this were a more traditional “review” of the camera, the logical step would be a comprehensive analysis of the photographer’s experience when shooting with the Contessa. This would then provide the necessary formula for a judgement of the camera’s potential value, usability, quality of lens, exposure accuracy, etc. However, I endeavor to provide no such thing. In fact, I am purposefully evaluating the 1953 Zeiss-Icon Contessa on aesthetics, design and appointments only. In this way, I am isolating the camera as a discrete artifact.

The Five-Part Construct

I’ve come to terms with my heavily compartmentalized and (Marxist) understanding of photography and destined to reach some level of clarity, have broken it down into individual discrete components. The sum of which is that functional apparatus (which includes the system of perspective that articulates a privileged point of view) that we know as Photography. The five components follow:

One: “The Camera”

The actual device that allows the “operator” to access the other components of the functional apparatus. Obviously not limited to the contemporary notion of “camera-ness,” this includes the Camera Obscura in all forms. The essential vessel through which the following two systems can operate.

Two: “The Act of Photography”

Basically, the steps involved in utilizing a “camera” to initiate and execute the event or the “camera-less” event. (Photograms, Man Ray’s Rayograms, Direct contact printing, etc.) This includes that choice of device, film/paper selection, lens selection (where applicable,) loading the film/paper into the device. In addition, the actual operation is considered; the cocking of the shutter, the turning of the lens barrel to acquire proper focus, the movement of the aperture ring, and ultimately the actual pressing of the shutter button. The process repeats.

Three: “The Subject”

The semiotic depiction of reality. Very specifically a particular representation. i.e., “this” rather than “any.” (I am photographing “this” tree and not “any” tree.)

Four: “The Photographic Process”

The point at which a representational image is realized. That is the distinct formulaic chemical reaction resulting in excited silver halide crystals rendering a latent image.

Five: “The Photograph”

The representation of the semiotic depiction of reality.

The Marxist Dialectic and The Photographic Apparatus

I realize that I’m going out on a limb here. Way out. On a thin, very precarious, very presumptuous limb.

At a certain point in my association with image-making, I began to see the “The Act of Photography” as a discrete event. And as I pushed this idea further, I realized that “The Photograph,” that is the representation of semiotic reality, was the product of a collision of two distinct components of the apparatus, “The Camera” and “The Act of Photography.” “The Subject” is a catalyst that drives aesthetics and establishes point of view, and “The Process of Photography” is simply the photochemical bridge between the pragmatic elements (camera/act/subject) and the photograph.

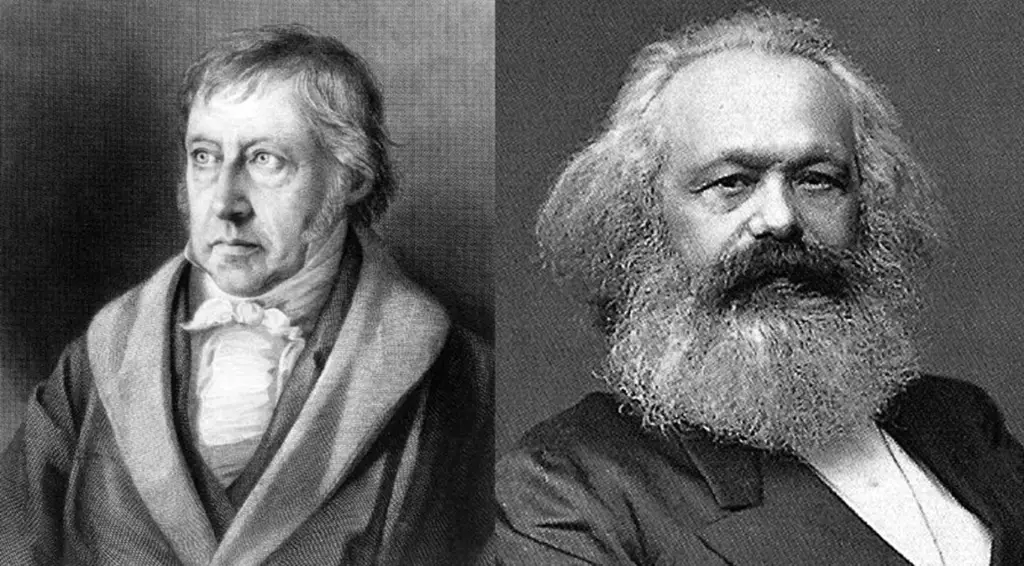

The “Dialectic” Duo

The Dialectic, derived from Hegelian philosophy and the basis for Marx’s justification for proletarian radicalism and revolution presents the opposition of ideas/concepts (Thesis/Anti-Thesis) as a fluid dynamic yielding a new, more advanced idea/concept (Synthesis.) This is an obvious simplification, but I believe that “it does the trick” and allows for the forceful manipulation of the reigning concept to fit my theory. The Dialectic is also attributed to S. M. Eisenstein’s approach to Cinematic Montage passionately explored in Battleship Potemkin (1925) and more so in October (1927.)

By stripping away the other components of the apparatus and thus demystifying “Photography” as a system through which we articulate representation, I believe that it is possible to pinpoint the synthesized result when the “The Camera” and “The Act of Photography” intersect. Thus, the choice of “The Camera” (and everything that it encompasses) functions as a thesis and “The Act of Photography” (the set of parameters established to engage “The Camera” as a functional tool of representation) offers an anti-thesis of sorts, as it pushes against the rigid dogmatism of a particular camera’s operation. The synthesized result of the dialectical structure would be the photographer’s “approach” to rendering a subject, positioning themselves as a conduit between process and content orientation.

Baudrillard, The Simulacrum, and the Yashica Y35

As I stood back and contemplated the structural bedrock of my understanding of photography, I realized that I had inadvertently tapped into a system of representation that derives its meaning from the actual breakdown of the underlying apparatus. Thus “The Camera” and “The Act of Photography” would provide the necessary ingredients in a formula that renders a latent image. However, at this point, I had theorized two discrete, separate components. The Yashica Y35 offers an augmented representation that combines these two elements into a single, unified construct.

Produced and released in 2018, the Yashica Y35’s existence was the product of a fairly robust Kickstarter campaign destined to bring the first digital film camera to the World of Photography. A hybrid oxymoron that pulled together the traditional components of analog photography and the sublime nuance of digital technology, the Yashica Y35 was received with some fanfare but ultimately fell to the harsh criticism of the “photography review” and all but vanished from the industry landscape. Still, the Yashica Y35 caught my attention and by all accounts, it appeared to fit into the post-structuralist mold that was the by-product of my theoretical meanderings.

The components of the Y35 include the camera body, a plasticized version of a typical Japanese 1960’s rangefinder and a set of six “digital film” cartridges. The photographer chooses a digital cartridge, opens the back of the camera, loads the “film,” closes the camera back, winds the camera and presses the shutter button. A photograph is taken, and the images are offloaded via USB to a computer. The only adjustment is a simple exposure compensation dial which offers the user minor EV control and a one second “shutter speed” for specific applications. The entire process is simple, straightforward, and purposefully sparse. Rationale replaces functionality. The missing view screen challenges the photographer. As stated in the website’s description,

“Every Y35 image is real. Using the (sic) Y35 is a journey to the truth. No instant gratification of a (sic) review screen. No deletion button. No hiding from mistakes (sic).”

“Realism” is guaranteed as is “truth” and “artistic” revelation.

The Yashica Y35 offers a unique form of representation in which “The Camera” and “The Act of Photography” are coordinated revealing a composite that functions within the apparatus. The “digital film cartridges” are attempts to faithfully reproduce a particular film stock, aesthetic, or format. (The six digiFilms are: YASHICA blue, in my fancy, 200, B&W, 1600, and 6×6) The sum of these parts suggests a hybridization that represents a simulation. The result; the perceived “act” of Film Photography.

To provide my observations with a basis of understanding, I needed a theoretical model to push against. I turned to the post-structuralist treatise Simulacra and Simulation by philosopher and cultural theorist, Jean Baudrillard. Positing a multi-lateral approach to understanding the sign/meaning construct, Baudrillard suggested four stages of delineation whereupon the relationship of a copy to an original is measured in terms of its “faithfulness of representation.” Each stage introducing a progressively radical analysis of the sign/order relationship. As the “faithfulness of representation” fragments, the simulacra (simulated reality) evolve and eventually replace the original, now decimated sign. I suppose, in terms of popular culture, the quartet of Replicants (Roy Batty, Pris, Leon Kowalski, and Zhora) featured in the film Blade Runner (1982, Ridley Scott) would be a straightforward analogy.

Each character evolving beyond the scope of its original construct and purpose. Unlike these replicants, however, the Yashica Y35 was not designed to function without its referent. In fact, in its role as a simulacrum, the simplistic camera is dependent on the original “Act of Photography” as it strives to represent a fully functional hybrid of the components of the photographic apparatus.

My observations are, by no means, meant to offer any sort of value judgement of the Yashica Y35’s worthiness or endurance as photographic gear. This article was simply an exploration of the dynamics of the photographic apparatus as approached from a Marxist, post-structuralist position. By forcing a theoretical wedge between the five individual constructs as I presented them, I feel that I have made some leeway in my own understanding of the role of “The Camera” in terms of what it represents rather than its traditional perceived ability to represent.

And if Replicant Roy Batty somehow found himself wandering around our society and happened to show up for one your Photo Walks, casually slung over his shoulder, loaded with some digital film, would be a well-mannered, unassuming Yashica Y35. An able simulacrum ready to replicate the “Act of Photography.” Profoundly and effortlessly.

About the Author: Michael Kaplan is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Theatre, Film, and Media Arts at The Ohio State University where he teaches Film and Video Theory and Production. He is the host of the popular podcast: The Ephemeral Machine: A Podcast about Collecting Cameras. Michael and his wife, artist and writer, Jesse Chandler perform as the Jazz standards duo, The Velvet Sirens. The live in Columbus, Ohio with their two dogs, Frida and Diego, and their cat, Pandora. You can find The Ephemeral Machine on Instagram and Facebook. Check out The Ephemeral Machine: A Podcast About Collecting Cameras on Podbean, Apple Podcasts, Spotify and other popular podcast platforms.

Share this post:

Comments

thorsten on Latent Postmodernism and The Act of Photography: Deconstructing the Yashica Y35 – By Michael Kaplan

Comment posted: 24/01/2022

Comment posted: 24/01/2022

Martin Siegel on Latent Postmodernism and The Act of Photography: Deconstructing the Yashica Y35 – By Michael Kaplan

Comment posted: 24/01/2022

Comment posted: 24/01/2022

JAMES LANGMESSER on Latent Postmodernism and The Act of Photography: Deconstructing the Yashica Y35 – By Michael Kaplan

Comment posted: 24/01/2022

Comment posted: 24/01/2022

Arthur Gottschalk on Latent Postmodernism and The Act of Photography: Deconstructing the Yashica Y35 – By Michael Kaplan

Comment posted: 24/01/2022

Comment posted: 24/01/2022

Scott Gitlin on Latent Postmodernism and The Act of Photography: Deconstructing the Yashica Y35 – By Michael Kaplan

Comment posted: 24/01/2022

Comment posted: 24/01/2022

David on Latent Postmodernism and The Act of Photography: Deconstructing the Yashica Y35 – By Michael Kaplan

Comment posted: 25/01/2022

Comment posted: 25/01/2022

David Hume on Latent Postmodernism and The Act of Photography: Deconstructing the Yashica Y35 – By Michael Kaplan

Comment posted: 25/01/2022

Comment posted: 25/01/2022

Alan Chin on Latent Postmodernism and The Act of Photography: Deconstructing the Yashica Y35 – By Michael Kaplan

Comment posted: 25/01/2022

Gary on Latent Postmodernism and The Act of Photography: Deconstructing the Yashica Y35 – By Michael Kaplan

Comment posted: 25/01/2022

Comment posted: 25/01/2022

Comment posted: 25/01/2022

Comment posted: 25/01/2022

Comment posted: 25/01/2022

Lee on Latent Postmodernism and The Act of Photography: Deconstructing the Yashica Y35 – By Michael Kaplan

Comment posted: 25/01/2022

Comment posted: 25/01/2022

James Ollinger on Latent Postmodernism and The Act of Photography: Deconstructing the Yashica Y35 – By Michael Kaplan

Comment posted: 25/01/2022

I find it very hard to separate #2 and #4, as I believe they're part of the same thing. The settings chosen for the camera--shutter speed and aperture--have as pronounced an effect on the image capture as does properties of the film, the paper (if used), the chemical treatments, and any other physical manipulation during or after processing the image, be it a reversal transparency or a print.

I might argue, unless I'm completely off track, that #1 and #2 and #4 are closely integrated due to the physical properties of the camera. There's a platonian ideal of a camera that's describe and drawn on an engineer's worktable, but the real camera that's manufactured rarely matches it, and no two cameras manufactured are going to be identical. Due to misalignment of lenses, optical defects, optical performance compromises, a misalignment in the mount, a fault in back pressure plate (if there is one), are going to affect the image because of the image may or may not be in the same focus across the film plane; there may be optical defects, halation, misregistration, camera shake, and other things that change the image. Exposure changes depending on how accurate or even consistent the shutter speeds and aperture stops are. In short, the Camera, the Film, the exposure, and the subsequent mechanical process to produce a final image are all inextricably interlinked.

If you want to make a case for a camera's value existing outside of its function, I think that can be done. Human beings have, for almost as long as can tell, seem to have made things that a) were decorated to be beautiful even when the beauty had no actual functionality (decorated pots), and b) made things that did not appear to have any real functional value (e.g. carved figures), because they brought us some kind of pleasure looking at it. We fill museums of pots and trinkets of all kinds sometimes because they're very old, but often because they're just beautiful, not because they're a particularly good container of beans, or a warm blanket, or a shield against rocks and arrows.

We're not the only ones who do this sort of thing. You can easily find master woodworkers who have a wall full of old tools that they would never use for a job, but are proud to exhibit because that tool has some sort of meaning invested by the owner. Maybe it's finely crafted. Maybe it was designed with a unique idea. Maybe it was held in the hands of a master 100 years before and played a part in making some fantastic piece of furniture. Concert musicians keep obsolete instruments. Pharmacists may have old apothecarys' cabinets full of ancient powders and useless cures.

I collect and keep cameras for a variety of reasons, and different cameras for different reasons. Some are beautiful. Some are interesting. Some have a story. Some are artifacts. Some are family heirlooms and have the fingerprints of ghosts on them. Some are tools.

Again, forgive me if I've completely missed the point of this article.

Mark Kayuda on Latent Postmodernism and The Act of Photography: Deconstructing the Yashica Y35 – By Michael Kaplan

Comment posted: 26/01/2022

Joyce Harrison on Latent Postmodernism and The Act of Photography: Deconstructing the Yashica Y35 – By Michael Kaplan

Comment posted: 29/01/2022

I enjoyed reading your essay. As a reader, I would follow you anywhere on your "precarious, presumptuous limb"...metaphorically speaking. I would also love to see your camera room!! Bravo, wonderful writing!!

Bud Sisti on Latent Postmodernism and The Act of Photography: Deconstructing the Yashica Y35 – By Michael Kaplan

Comment posted: 02/02/2022