Introduction: by Sroyon

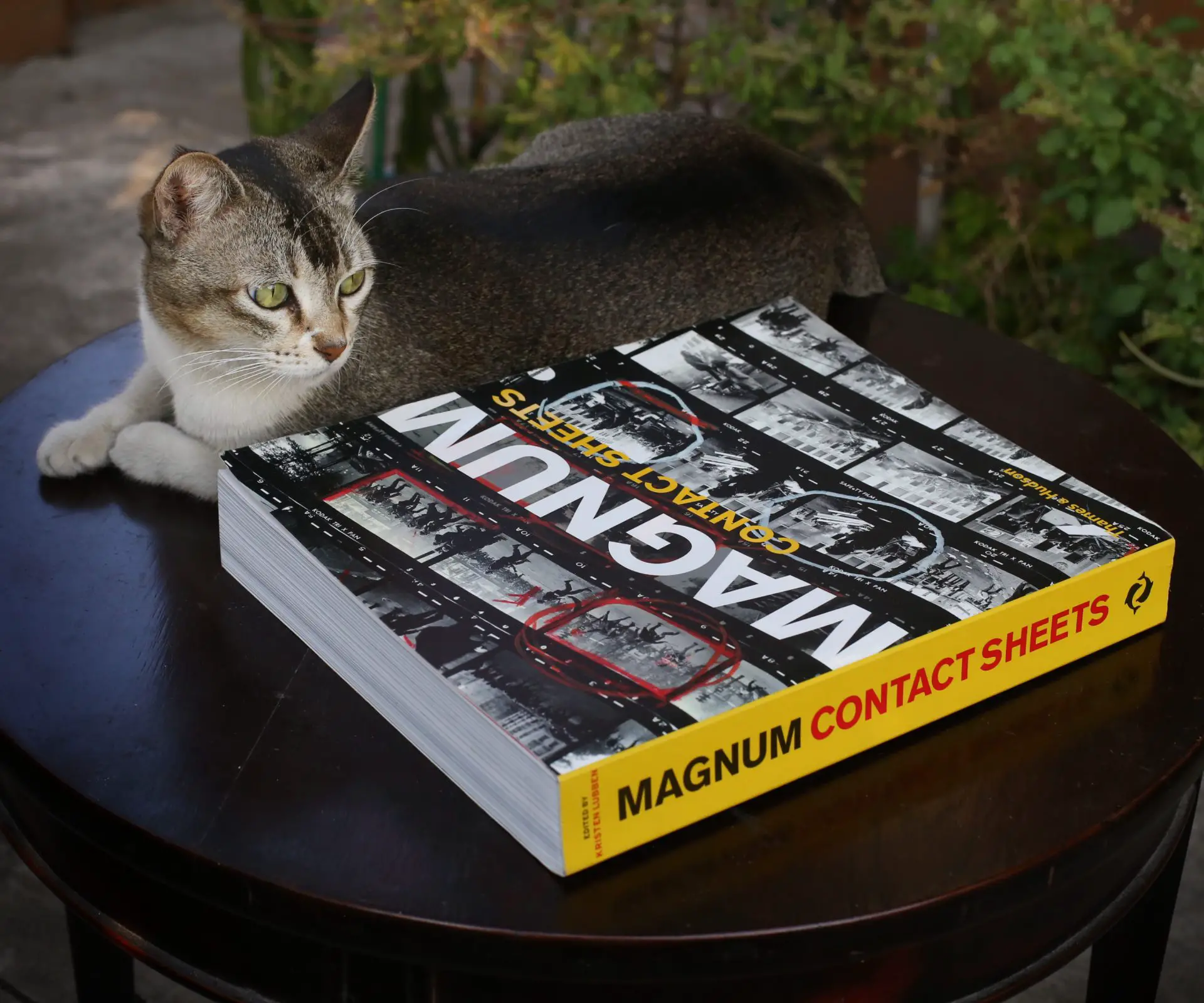

Magnum Contact Sheets edited by Kirsten Lubben

Thames & Hudson, 2018 (first published 2011), 524 pages, paperback

The average 35mmc reader perhaps needs no introduction either to Magnum, or to the concept of contact sheets. But just in case, Magnum Photos, founded in Paris in 1947, is one of the world’s most famous photo agencies. It’s a cooperative owned by its members, who have included such luminaries as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa (both of whom were founding members), Eve Arnold, Dorothea Lange, and Sebastião Salgado – to name just a few!

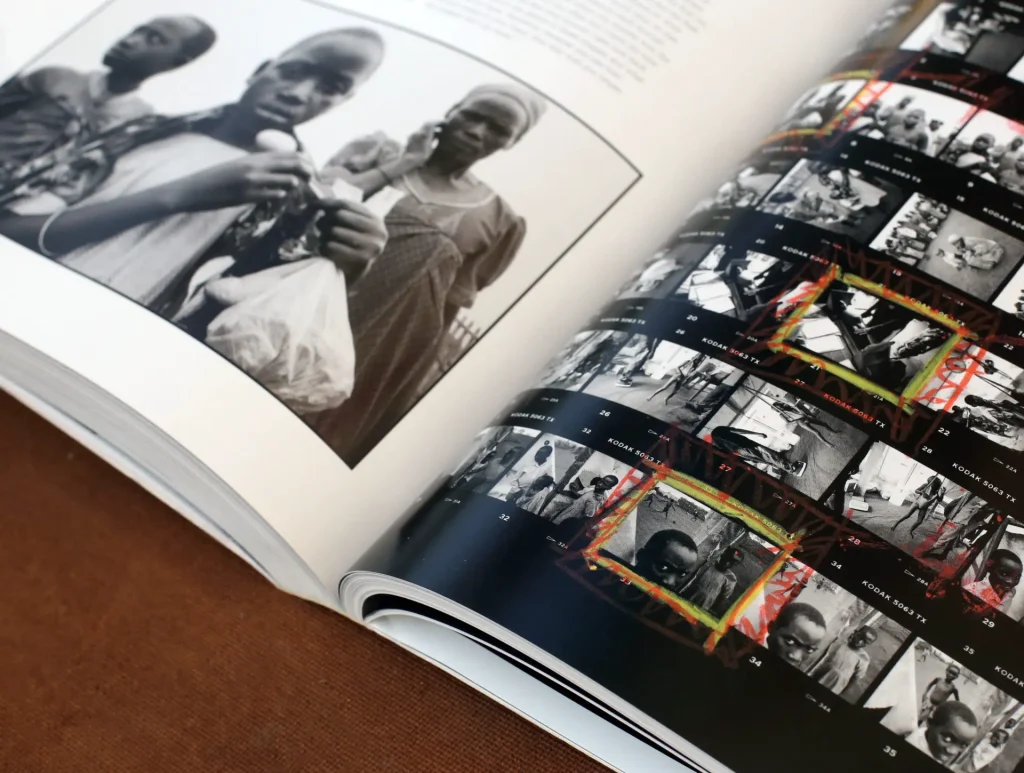

A contact sheet is a sequence of negatives printed directly onto photographic paper (I recently wrote a post about making contact sheets, if you’re interested). The negatives are printed not by enlargement, but by placing them directly on – in contact with – the paper. Contact sheets let you review a whole roll at a glance, albeit in miniature. Often, just one or two photos from a roll are chosen for publication, if that; the rest never see the light of day. Thus, contact sheets can provide a “sense of walking alongside the photographer and seeing through their eyes”, a “uniquely intimate glimpse into their working process” (p9).

Magnum Contact Sheets presents the work of 69 photographers – 139 contact sheets featuring some of the most famous photographs in history, along with enlargements of individual photographs. The contact sheets are mostly from black and white negatives like the one shown below, but we also get some colour negatives (like Jonas Bendiksen’s magic-realist Satellites) and transparencies (like Stuart Franklin’s iconic images of Tiananmen Square).

The entries are organised into seven chronological sections, starting with 1930–49 and ending with 2000–10. Each entry also contains a short note written by the photographer (or in case of photographers who are deceased, by an expert) about the photograph.

I’ve had my copy for over a year now, and it’s one of my favourite photography books. But it’s a behemoth of a book – 2.8 kilograms for a paperback! – and I tend to dip in and out when I feel like it, so I thought I don’t know the book well enough to write a review. So when Holly, whom I know through the 35mmc community, mentioned that she recently got a copy and was planning to read it more systematically, I thought of writing one with her.

In the next section, Holly talks about her impression of the book. And at the end, I add my own less organised musings, somewhat mimicking my more random, lucky-dip style of interacting with the book.

Review, part 1: by Holly

This book fell into my possession relatively recently. It was a much anticipated birthday present which, due to covid, was posted rather than handed to me. Imagine my confusion as I picked up the package from my doorstep, wondering what on earth could be inside such a heavy box.

Ladies and Gentlemen, I present Magnum Contact Sheets.

I think the size of the book made me feel a little wary of starting it. I eyed it with excitement but always opted for something a little thinner first. And then Sroyon asked me if I would be up for a joint review and that was the kick up the backside to actually get it out. If you are sitting on the fence about purchasing this book, or picking it off the shelf, like me, I heartily recommend you do. It is magnificent.

When you consider that the majority of this book is full pages of contact sheets or enlargements of individual images then it really isn’t so scary. A word of advice though. This is a book to be enjoyed in excellent lighting – perhaps gorgeously lit from the side by a bright window – not the light of a dim bedside lamp, which is how I read it as I only really get about 20 minutes before I go to sleep to read anything.

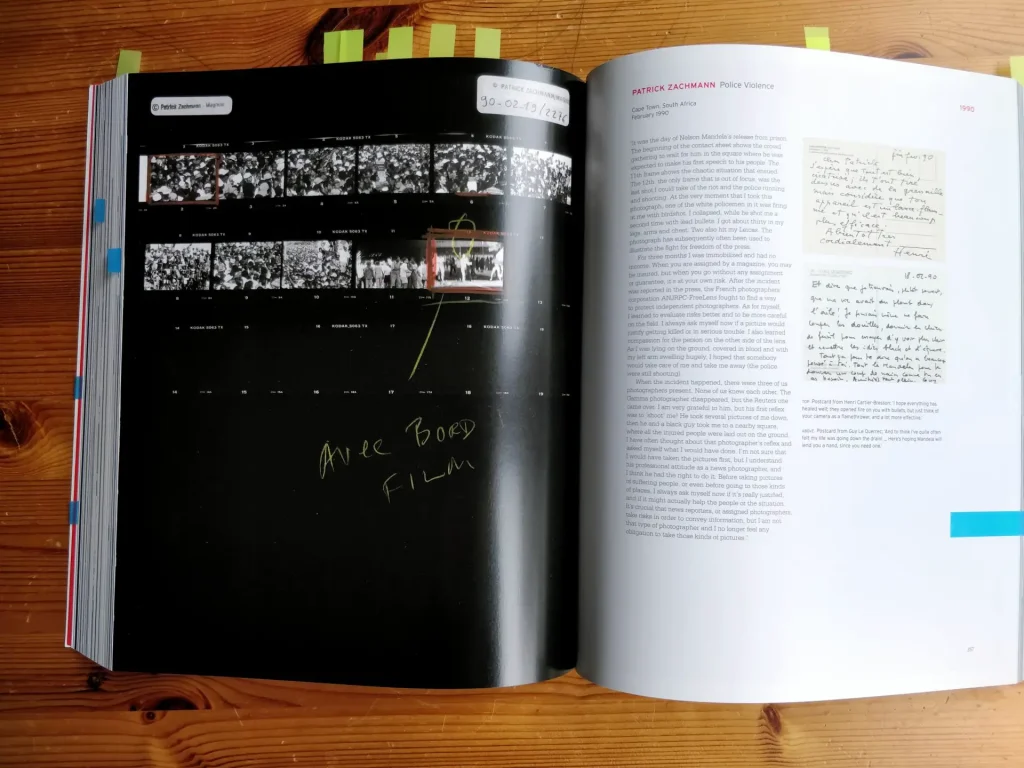

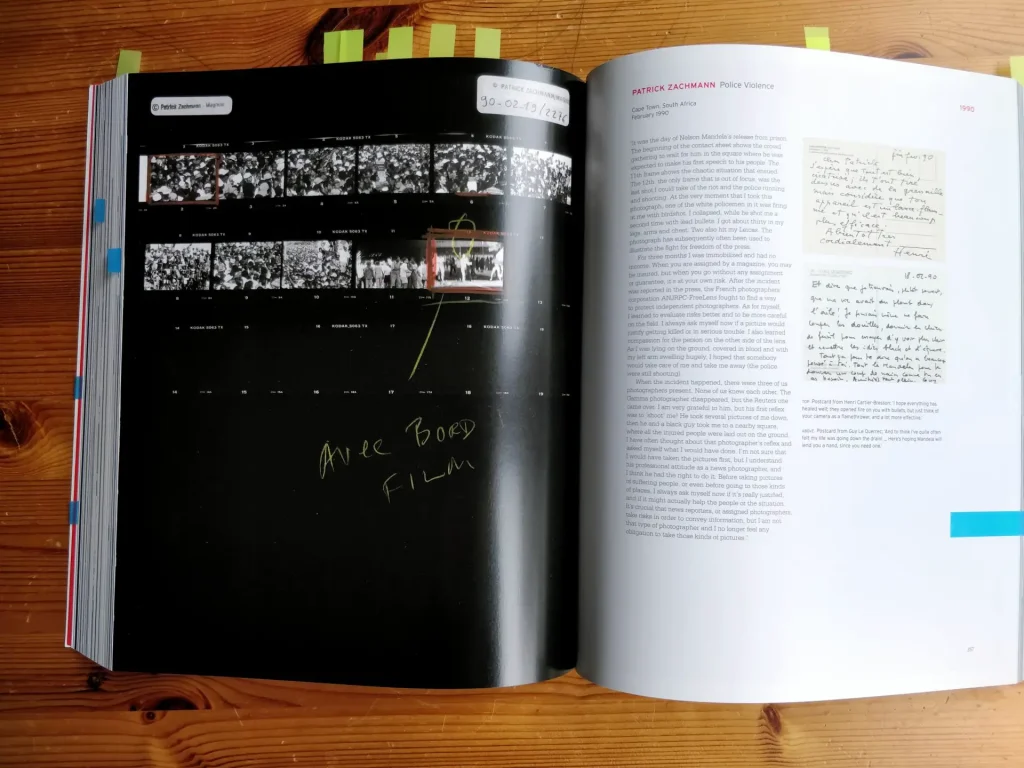

Depending on the book, I will usually put markers in, perhaps in pencil or, in the case of glossy pages like this, little post-it markers. As you can see from this picture, I had a lot of things I wanted to refer to! The yellow tabs are photographers I want to go back and explore further and the blue tabs are quotes or thoughts that I wanted to share.

I absolutely love the series of posts on 35mmc in which people share a full roll of film. Not many people are actually willing to do this, especially when you compare it to the number of people who do 5 shots posts! This quote from the book perfectly sums up why people are not clamouring to share a whole roll:

The illicit quality of the contact sheet is the source of much of the viewer’s fascination with it. Like reading someone’s diary or looking in their closet, the contact sheet is not meant for public consumption. (p10)

Thus far, I have only made 1 contact sheet (I’ve only ever spent 1 day in a darkroom though!) but it is the thing I’m most excited to try first when I finally get my own one up and running. I want to make contact sheets of all my rolls of film and spend time poring over them. Something I just can’t imagine doing with the shots I take digitally…

While these systems [digital] may be highly functional for the short-term trafficking of images, it remains to be seen how enduring they will be. Will scholars of the future be able to pore through outdated digital files as they do through prints, contact sheets and paper files, and how will that fundamentally different experience of the archive shape the histories that are written of the current period of photographic production? (p13)

A very interesting question and one we can hardly answer whilst we live it. I also think that there is a clear distinction between photojournalism (which the majority of the examples in this book are) and personal images. I have recently come to the realisation that for me, in my own practice, film photography is about art, and digital (specifically my phone) is about capturing daily life with my children. This is why I don’t enjoy using point and shoot film cameras and why I love scrolling back on my phone to pictures of my children as tiny babies. Of course that could change, these things tend to evolve with time but in this moment, this is how I feel. And so I question whether historically and educationally contact sheets are important, but for our personal daily images, digital allows us to snap and return to beloved memories so much quicker. I don’t know, it’s all opinion really!

No longer an active working tool for most photographers, the contact sheet is relegated to the archive, of interest as a historic document. Its value there may yet prove even greater than its original workaday function; an enduringly accessible record of what and how photographers saw for nearly a century. (p14)

What drew me to this book was the concept of seeing the creative process in action. I may not be watching the photographer actually taking the photographs but, where a photograph can lie, I would argue that a contact sheet does not. You can see whether it took the photographer one shot or the entire roll to get that perfect image, if it took them a few frames or a whole roll you can see how they experimented with angles, framing, composition, etc… (I concede that there are instances where a contact sheet lies, even in this book there are examples of using contact sheets to tell a narrative, but broadly speaking the contact sheet is far more truthful than a single image).

The contact shows Erwitt’s patience, shooting around an image methodically until he has all the elements synchronized for maximum effect. As he says, “It’s a lot of pictures getting to the good one.” (p457)

There are a few different ways I can imagine someone reading this book and I can see myself doing each of them:

- Read it from cover to cover – as I have this time.

- Use it as a reference when looking for a specific photographer’s work.

- Dip in and out, randomly selecting sections to look at – which I believe is Sroyon’s method.

I’m going to jump forward to 1964 and an entry by David Hurn in which he was photographing the Beatles. He says:

The contact sheet is a valuable teaching instructor. Presumably, when a photographer releases the shutter, it is because he believes the image worthwhile. It rarely is. If the photographer is self-critical, he can attempt to analyze the reasons for the gap between expectation and actuality … Ruthless examination of the contact sheet, whether one’s own or another’s, is one of the best teaching methods. (p159)

So well put! I’ve found the process of scanning my negatives and checking the full roll over a lightbox has massively improved my photographic knowledge.

As you can see from my sticky labels, there are a lot of photographers that I want to go back and revisit, research and learn more about but there was one that I wanted to share here. The entry for Patrick Zachmann in 1990 in which his roll of just 11 shots shows the moments leading up to him being shot by a white policeman. His cameras were broken and he himself was out of action for 3 months. In his description of the contact sheet he talks philosophically about what an image is worth and the value of the life on the other side of the lens. And it’s with this quote that I wanted to end my review. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this.

I hoped that somebody would take care of me and take me away … there were three of us photographers present. None of us knew each other … his first reflex was to ‘shoot’ me! He took several pictures of me down, then he and a black guy took me to a nearby square … I have often thought about that photographer’s reflex and asked myself what I would have done. (p357)

Review, part 2: by Sroyon

Magnum Contact Sheets is presented chronologically, but in practice, I tend to open the book at random, study a few entries closely, and put it back on the shelf. In the same spirit, and since Holly has written an proper review already, I thought I’d pick three entries in no particular order and briefly talk about them – taking you with me on this haphazard journey.

We start at page 239, about midway through this giant book.

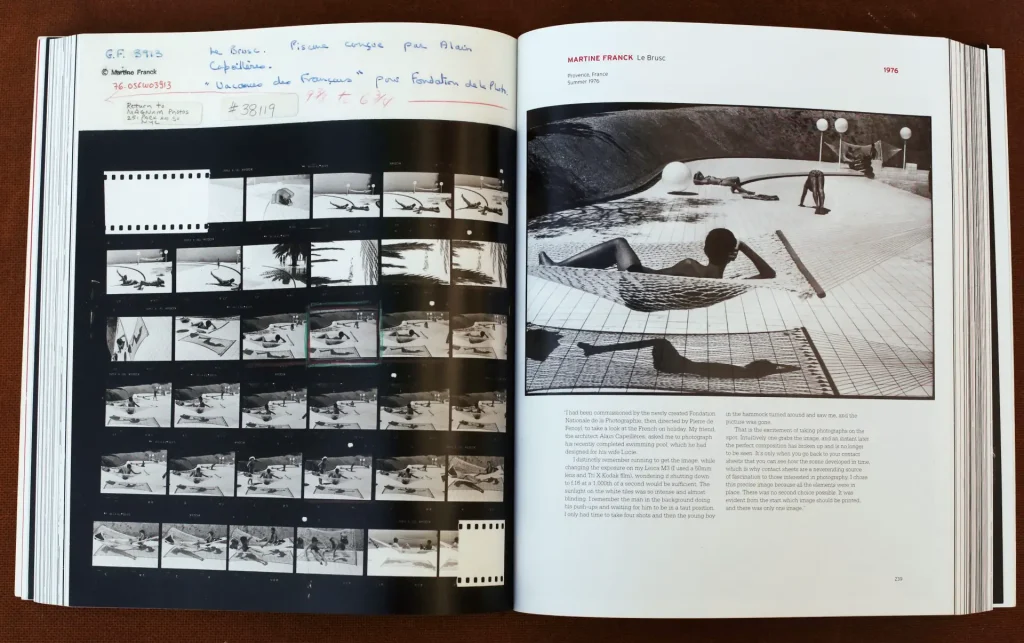

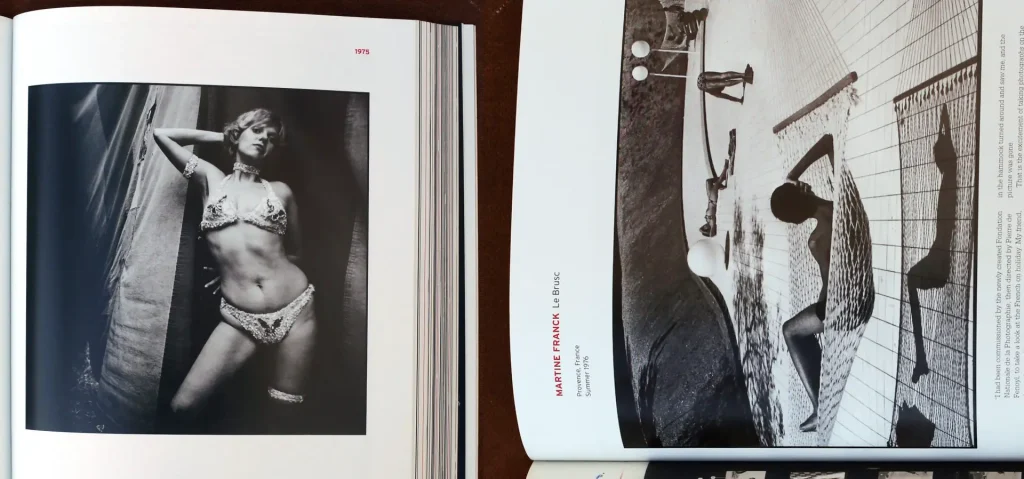

The photograph is Martine Franck’s Le Brusc (link has some nudity). It’s high noon in Provence, France, in the summer of 1976. In the middle-distance, a woman in a bikini is sunbathing on a white tiled floor which gleams so bright it almost makes you squint. A man is doing push-ups. In the foreground, a boy reclines on a hammock, idly contemplating the scene, just as we contemplate the scene with him. His form is mirrored by his shadow on the ground – and also mirrored, elsewhere in the book, in Susan Meiselas’ portrait of Lena, from her Carnival Strippers series (again, link has some nudity). In this way, my ‘channel-surfing’ approach finds unexpected and unintended connections and contradictions.

Franck’s contact sheet shows how she approached the scene. A few shots from the reverse angle, with Sunbathing Woman and Push-Up Man in the foreground and Hammock Boy in the background. Some photos of palm trees and shadows – a momentary diversion. And then she notices the boy’s shadow on the ground. Two shots just of him and his shadow, but then she recomposes to include the figures in the background. Four photos, one of which is the ‘money shot’. Then the boy notices her presence and turns around. The moment is gone.

In the text, Franck describes running to the scene with her camera, “my Leica M3 (I used a 50mm lens and Tri X Kodak film), wondering if shutting down to f.16 at a 1,000th of a second would be sufficient” (p239). For me, some of these first-hand accounts are as interesting as the pictures, if not more so. We find out what drew the photographer to the scene, the equipment they used, the challenges and uncertainties they faced.

And indeed, the challenges are sometimes far more grievous than, say, the possibility of overexposing Tri-X. Consider Gilles Peress’ account of photographing the events of Bloody Sunday in Northern Ireland, January 1972:

I know that at one point I was shooting and crying at the same time. I think it must have been when I saw Barney McGuigan dead … He was alone. Then a priest arrived and started to give him the Last Rites. I remember taking a few pictures then. I also remember that I didn’t want to intrude too much, but at the same time I felt this obligation to shoot, to document. It’s always the same fucked-up situation: you are damned if you do and damned if you don’t… (p209)

Page 513: we’ve jumped almost to the end:

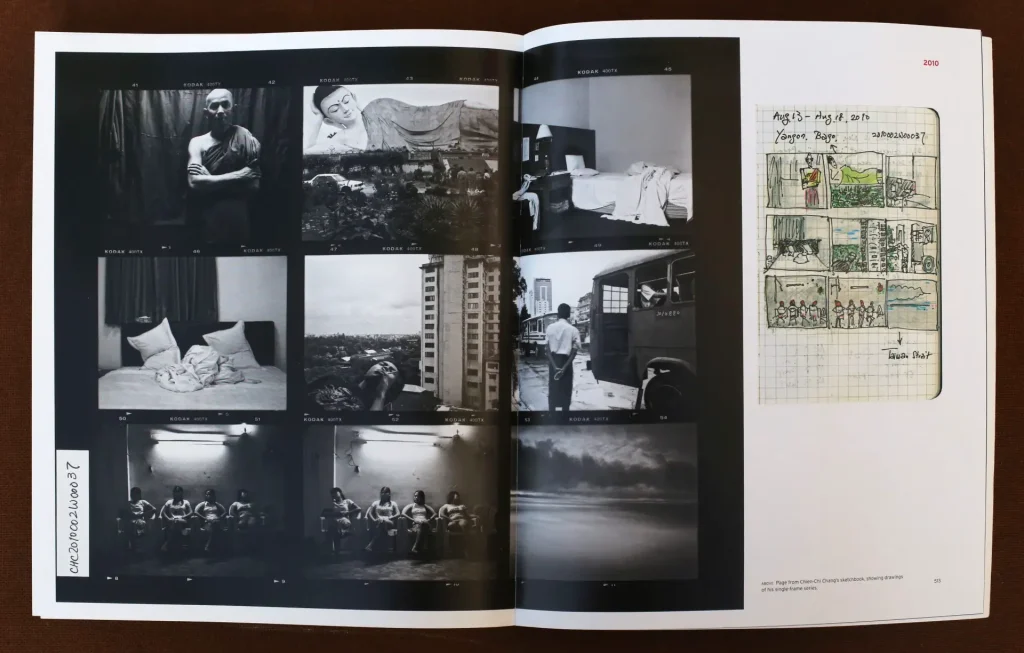

On the left are medium-format contact prints from Chien-Chi Chang’s Travelogue series (2010). A monk gazes placidly at the camera. A statue of the Buddha – another reclining figure! – dwarfs the humans in front. An unmade bed in a hotel room. Unlike Martine Franck’s contact sheets, there’s no evidence of ‘working the scene’. One shot, make it count.

Chang’s text confirms what the contact sheets suggest:

I feel that one shot is enough. Sometimes I might feel I’m missing the so-called ‘decisive moment’, but when you accept that you’re going to shoot this way, you accept that you’ll be missing something: you win some, you lose some. I take pictures increasingly slowly, trying to make every frame count even more. I spend time watching, observing, interacting. Sometimes I feel, ‘enough’, and I put down the camera and have a bowl of tea. (p510)

I think I have got more out of these reflections, and from careful perusal of the contact sheets, than I have from many technical books about photography.

On the right is a page from Chang’s notebook, with sketches of the scenes he shot. I assumed he drew them with his contacts sheets as reference, but that’s not the case: “I sketch as soon as possible after taking a shot, usually at the scene itself. Otherwise, I might forget” (p510). His drawings are astonishingly accurate.

The book also has reproductions of notebook pages of other photographers, along with magazine clippings, press cards, letters and other ephemera. The contact sheets, too, are marked with coloured ink, symbols, stickers and labels. Some are cut up, disarranged or – as with Jim Goldber’s Signing Off – deliberately disfigured. Together, they are vivid reminders of the tactile, physical quality of photography in the analogue age – a quality we find even in the very name: contact sheet.

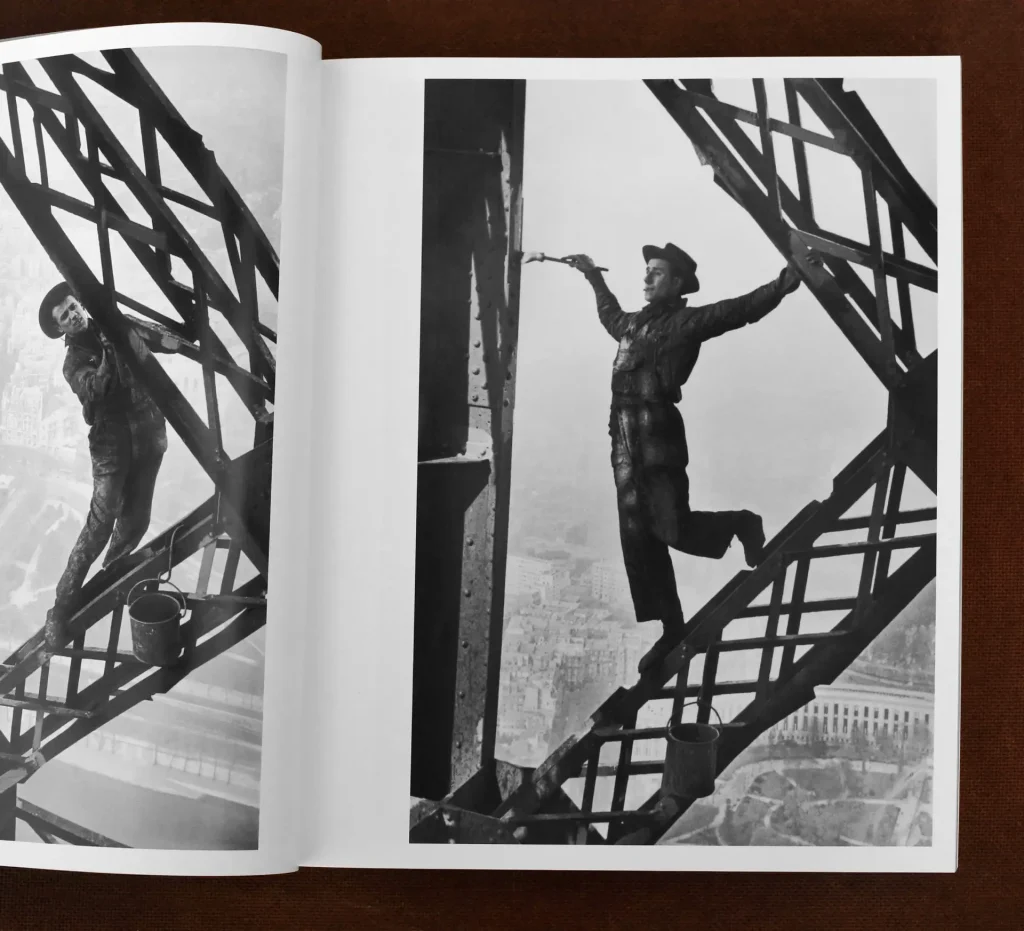

We end almost at the beginning – on page 77, with a photograph from the city where Magnum was founded.

High above Paris, Marc Riboud’s Eiffel Tower Painter (1953) dances with his paintbrush – hat tilted at a jaunty angle, a cigarette dangling from his lips. The photograph is iconic, but I had not seen the contact sheets before. They unfold like a music-hall routine. The painters – there are several – clamber up and down the girders, curve their bodies into improbable angles, stand on tiptoe like ballet dancers as they reach up to paint overhead.

Magnum Contact Sheets is a weighty book, dealing with many weighty subjects – war (Josef Koudelka, Prague Invasion), natural disaster (Gueorgui Pinkhassov, Earthquake in Armenia), birth (Cristina García Rodero, Maternity Ward), death (Robert Capa, Leipzig) – but Zazou the painter, as portrayed by Riboud, is lightness personified.

I’ve mentioned before how, for me, the photographers’ reflections add immeasurably to the value of book. Riboud’s text tells us he was walking the streets of Paris on his first visit to the capital, with just his Leica, a 50mm lens and a single roll of film. He notices the painters high above, climbs up the tower, and makes several pictures, among which is that unforgettable image of Zazou. “I think photographers should behave like him,” says Riboud, “he was free and carried little equipment” (p74).

We hope you enjoyed this review; if you’re interested in reading about photography, you’re welcome to join our Facebook group, Photography Books and Theory. You can also read more on Holly’s learning log, or follow us on Instagram: @schoolofholly (Holly) and @midtonegrey (Sroyon). Thanks for reading.

Share this post:

Comments

Daniel Castelli on Magnum Contact Sheets – Book Review – by Holly Gilman and Sroyon Mukherjee

Comment posted: 26/01/2021

Looking at the contact sheets made me feel like I was walking with the photographer as they shot the subject. You could literally watch as the photographer moved about the scene. Then, you could imagine them in the office or lab peering over the sheets with a loupe and china marker, talking over the selection with a colleague or editor.

I got the book that day (Holly is correct, it's damn heavy - and stuffed into my messenger/camera gave me a sore neck as I continued to wander about) and I return to it on a regular basis.

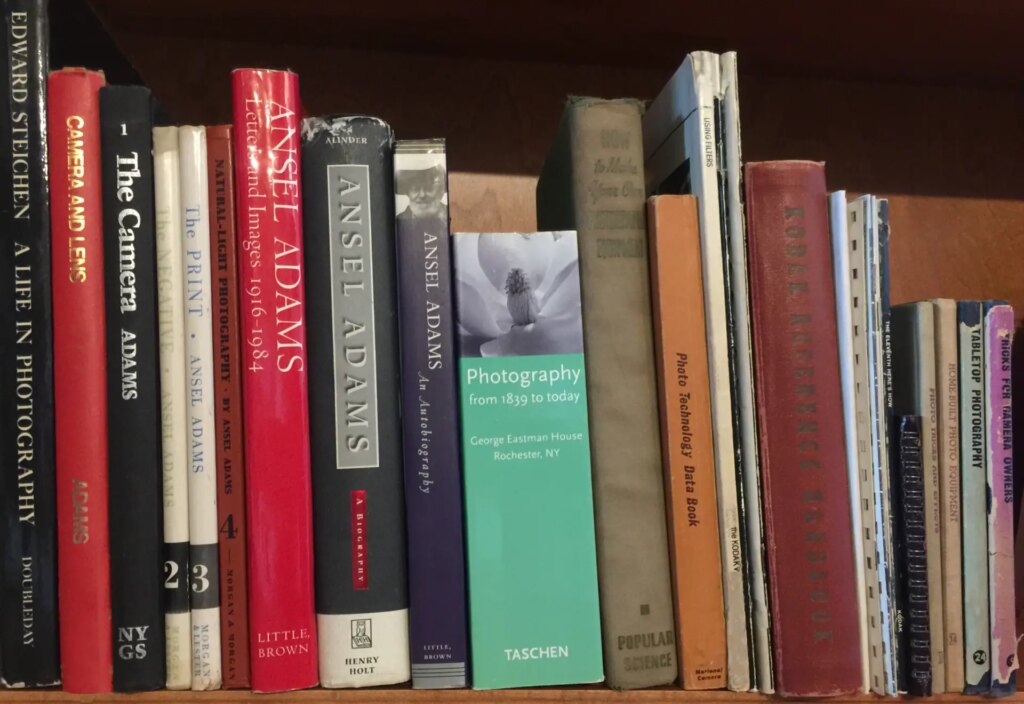

I'm a photo book collector. This book is on my list of 13 - one of 13 books I'd take with me to keep if I had to sell my entire collection. That's how important the book is.

Comment posted: 26/01/2021

Castelli Daniel on Magnum Contact Sheets – Book Review – by Holly Gilman and Sroyon Mukherjee

Comment posted: 26/01/2021

2. Obama by Pete Sousa

3. Margaret Bourke White by Stephen Phillips

4. Georgia O’Keefe by John Loengard

More to follow...

Comment posted: 26/01/2021

Bill Brown on Magnum Contact Sheets – Book Review – by Holly Gilman and Sroyon Mukherjee

Comment posted: 26/01/2021

Comment posted: 26/01/2021

Comment posted: 26/01/2021

Ted on Magnum Contact Sheets – Book Review – by Holly Gilman and Sroyon Mukherjee

Comment posted: 26/01/2021

I have the book and Holy and Sroyon have done us a service in their review, it is hefty and tells many stories. But what’s left out of this book is as intriguing as what is in it. On that account I would suggest reading “Magnum Fifty Years at the Front Line” by Russell Miller. An unauthorized biography of the agency, it will open your eyes to the personalities behind the iconic images. Bruce Davidson and Burt Glenn screaming at each other’s inches apart because Bruce called Glenn a prostitute for taking on commercial work, Philip Jones Griffiths refusing to attend a AGM and the subsequent failed kidnapping of him by other members. The account of John G Morris picture editors frustration with the tantrums and the liability of W Eugene Smith to the agency. I could go on, but if you are a devotee of Magnum as I am it’s almost required reading. Again great review Holy and Sroyon , thanks for starting my morning with this thought provoking review. Allbest

Comment posted: 26/01/2021

Comment posted: 26/01/2021

NigelH on Magnum Contact Sheets – Book Review – by Holly Gilman and Sroyon Mukherjee

Comment posted: 26/01/2021

Comment posted: 26/01/2021

John Earnshaw on Magnum Contact Sheets – Book Review – by Holly Gilman and Sroyon Mukherjee

Comment posted: 27/01/2021

Comment posted: 27/01/2021

Huss on Magnum Contact Sheets – Book Review – by Holly Gilman and Sroyon Mukherjee

Comment posted: 28/01/2021

A very interesting read.

Comment posted: 28/01/2021

Rob Mann on Magnum Contact Sheets – Book Review – by Holly Gilman and Sroyon Mukherjee

Comment posted: 18/02/2024