The word Leica and film often brings up precision, manual operation, best-in-the-world optics, and ideations that shooting a Leica automatically makes one a professional – if not overtly wealthy – photographer. The words Leica and Reflex typically give puzzled looks as many people are unaware of Leica’s reflex cameras that existed from 1964 through 2009.

Among Leica shooters, the word Leicaflex is often synonymous with a massively overbuilt by E. Leitz Wetzlar, 37,500 produced over two variations, idiosyncratic even in the mid 1960s, SLR that was priced in such a way that Leitz was nearly bankrupt and co-building cameras with Minolta less than 10 years later (the Leica CL / Leitz Minolta CL of 1971, the Leica R3 / Minolta XD-11 of 1976, and the Leica R4 / Minolta XG series of 1980 being 3 notable examples).

If this camera is reviled by so many – save those who actually shoot them and its successors the SL (1968-1974) and SL2 (1974-1976) – why has it become one of my two favorite cameras to shoot with?

What’s it like?

The Leicaflex Standard can be summed up as the offspring of a Leica M3, a Visoflex, and a hastily placed Leicameter MR that meters with the equivalent field of view of a 90mm lens. This results in spot metering for 35mm lenses, and places an effective meter usability limit of about a 135mm lens. Coincidentally, Leica telephoto M-lenses typically top out at around 135mm.

Released in 1964, the Leicaflex Standard was released at a time when its primary competition, the Nikon F, was moving towards through-the-lens metering with the Photomic meter, and Topcon had TTL metering in its cameras for several years. The Leicaflex Standard came in two variations; Mark IIs differ from Mark Is as they have a battery on/off switch in the lever advance that doubles for meter readings, a circle shaped exposure counter instead of a pie-shaped counter, and an integrated tripod mount instead of a tripod mount that is held into place by three Phillips-head screws.

Reflecting in 2018, it seems Leica acknowledged the Japanese onslaught of SLR cameras in the professional market, but ignored their rapid evolution by making a product aimed squarely at the Zeiss Contarex Bullseye. On the bright side, because of its unusual look, it has a little bit of outward stealth compared to a modern camera.

Build quality and operation

Loading the camera is an exercise in overbuilt. The backdoor is latched shut with a slide latch near the rewind that has an additional button to bolt the door shut. Thankfully, once the door is open loading is a one-handed exercise. Open the door, pull up the latch, jam the leader into the take-up reel, and drop the canister into the canister chamber. Close the door, advance twice, and make sure the rewind lever spins about. Once that’s done, set ISO and go.

In fact, setting the ISO does control the non-TTL meter, but because the camera is purely mechanical, it can serve as a reminder so long as the shooters sticks to (1 / filmspeed) at f/16 in sunshine, or 1/30 @ f/2.8 at ISO and derives the solution from there. This fully mechanical capability is limited to the Leicaflex series, but was resurrected in the R6 and R6.2 lines of the mid 1980s through mid 1990s.

Prepare for photographic tank warfare!

Be warned: The Leicaflex Standard is a SERIOUSLY heavy camera. The body alone weighs 880g and even the 90mm f/2.8 that’s on it is over 600g. Body and lens samples may have variation because at the time the Leicaflex line was built, all cameras were handbuilt to fit, resulting in potential variations among cameras.

That being said, this neck-snapping heft provides a feel that is reassuring; no plastic beyond the tip of the advance lever and the little hood around the light meter and the body is made of brass… VERY heavy brass. The lenses of the era are brass and aluminum and provide balance to this camera, pariticularly the 90mm f/2.8 that has become my primary street photography lens due to a balance of sharpness and focus precision due to its 270 degree focusing ring throw, balanced in-hand feel when combined with the Leicaflex Standard, and being period-correct with the Leica. (the body I shoot with is from 1966; the lens is from 1965).

Like driving a photographic Panzer!

This “tank warfare” quality continues to the shooting experience itself. I liken to being in a tank room, staring through the site; the lens is the barrel, and the shutter button is like shooting a tank gun. Whereas most Leicas are quiet due to being mirrorless rangefinders, the Leicaflex has a shutter, but an extremely overbuilt mirror system that slaps hard and makes a “thunk” noise. Testing whether this is because the mirror is overbuilt or whether there are other forces in play, I enabled the standard-exclusive mirror lockup feature. With the mirror out of the way, I tried again. Still a thunk sound… It seems the mirror and shutter mechanisms are both loud, and both contribute to the reassuring “thunk” noise of each shot.

The viewfinder is the final piece to “photographic tank warfare.” The viewfinder has a roughly .9x magnification, and it only allows for focusing in the center of the 92% viewfinder. Making matters worse, the prism and screen are not removable, unlike the Nikon F counterparts where screens and prisms can be changed for optimal shooting experiences. Additionally, the user can see the shutter speed and employ a match / needle system to determine correct exposure. Presumably, Leica felt interchangeability would reduce the robustness of the camera and was left out in production. The viewfinder is very bright, but it is prone to desilvering; thankfully while that may darken the view, it does not usually make viewing any more difficult with even 2.8 aperture lenses.

Attempts at Photography

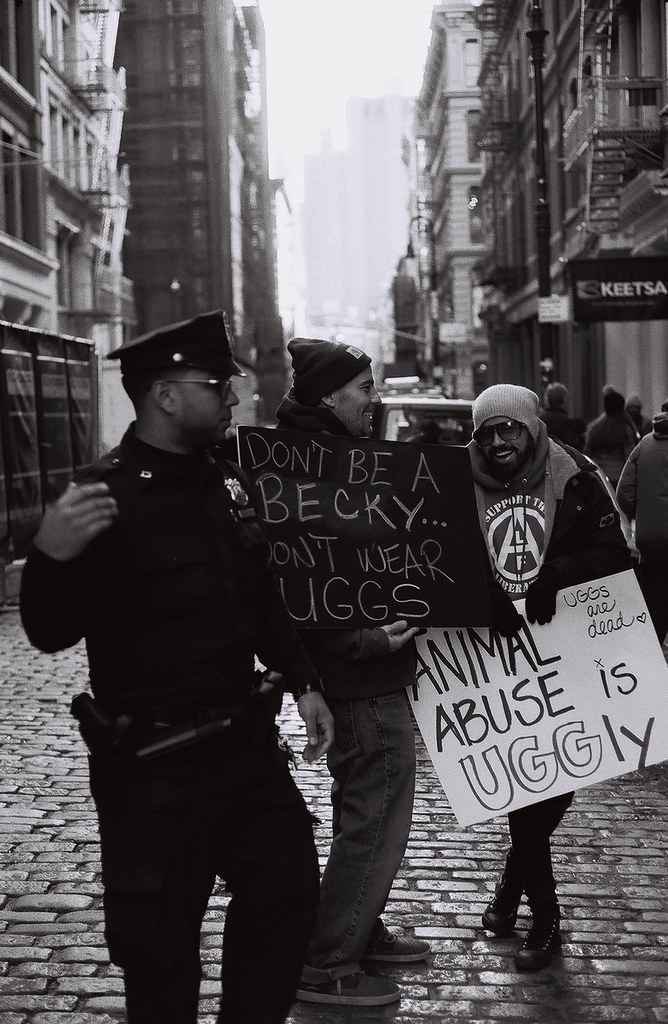

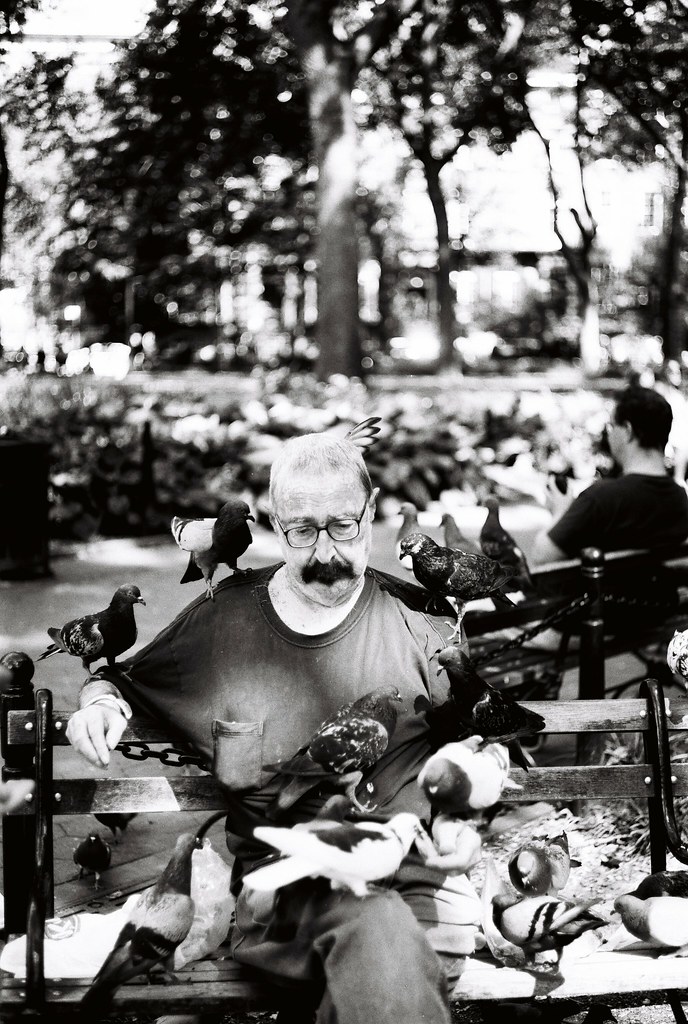

Leicas are often associated with street photography due to their ability to minimize intrusion into the environment around them. This is a byproduct of quiet shutters, small size, and yet extremely sharp optics for 35mm photography. The Leicaflex succeeds greatly in the third requirement, but fails spectacularly in the first two. Before I go further, that isn’t to say it is a bad street photography camera, but zone focusing – and failing that, fast enough film that your focus can be slightly off yet the picture still comes out as desired – become integral skills. Street photography can become a study of tank camera ballet. Bring the big camera to where you want to shoot (or if your subject may be skittish, zonefocus on something a bit past your subject), focus, wait, THUNK! And hope your subject is too wrapped up in his / her / their life / lives to notice. Typically the Leicaflex works, but there are times where if shooting close enough your subject may turn. The output though, is dynamic, a bit flat sometimes using color film, but with B&W the Leica shines; 1960s coatings were made for B&W, and it shines in street photography!

The Importance of film latitude

Shooting landscapes and cityscapes also bring to the forefront this camera’s strength, but getting up close to items can find an unexpected weakness. With the meter where it is, shooting cityscapes becomes easy if the meter is either aimed skyward, or during a bright day with relatively even lighting. A lack of modern amenities such as matrix metering, or even center-weighted metering – the camera’s meter area varies based somewhat on the focal length of the lens – means that one has to guesstimate the correct shutter speed without blowing out or underexposing details.

To this end, going to “extreme films” such as Rollei RPX 25 is a high-risk, high-payoff proposition. I find shooting with Portra 400, Delta 100, and Ektar 100 to be more consistent and workable with this camera. Yes, some detail may be lost to grain, but they work better with the Standard’s limitations than finer-grain yet less-forgivng films. That’s fine though, there are more modern cameras such as my F3 that meter dead-on and can deal with unforgiving films, there’s still something about Leica rendering that can’t be fingered.

If the Leicaflex is so great to use due to its simplicity, is so well-regarded by those who shoot them (all iterations), and gives so much autonomy to the photography, why then was it ultimately a failure that took Leica from photographic tour de force in need of innovation to nearly out of business within a decade? While the Leicaflex’s idiosyncratic design and ignorance to the Japanese competition as a product is partially to blame, much of the blame lies on overpricing itself for the market, relying on a loss-leader model, and aforementioned slow-to-react model endemic to Leica in the 1960s.

How the Leicaflex Standard failed in a 1960s Pro Market…

The Leicaflex failed in a 1960s pro market for several reasons. First, it entered the market already outdated; the Japanese competition (Topcon, Nikon, Canon) had already moved to through-the-lens meters for better light accuracy for professionals who needed quick and accurate results vs. hoping that a system transplanted from the Leica M3 with Leicameter MR wasn’t metering the sky when a picture of a protest was needed.

The Leicaflex SL (1968-1974) fixed the non-TTL metering system by putting a spot meter behind the mirror, and the SL2 (1974-1976) introduced a more sensitive TTL meter, a better focusing system, and the ability to see both shutter speed and aperture speed without removing the eye from the viewfinder, but neither advancement was enough. The Leicaflex was viewed as a professional-quality camera that could be used by a professional, but was eschewed due to a reactive instead of proactive mindset towards innovating in the professional domain.

Build quality overload

Additionally, the Leicaflex was a cost failure for Leica. Leica used a “correct and fit” model in which each piece of the Leicaflex was corrected until it fit that particular camera. The end result is a camera whose build quality is largely unparalleled by any other camera on the market, but at a cost that was anywhere from 50 to 100 percent more than its Japanese contemporaries. In fact, the cost for a body was so great that each body was sold at a loss, with Leica hoping that the profits would be made up when consumers bought multiple lenses for their Leicaflex. Sadly, this was not the case. Cameras such as the Nikon F may not have had the same extremely overbuilt nature as the Leicaflex (and other German SLRs), but they were tough enough to survive Vietnam, were interchangeable enough to be adapted to a greater number of photographic situations, and were at a low enough cost that if one were to be worked to destruction or destroyed at work, would not be an undue strain on as many photographers’ budgets.

Limited Lenses

These costs and limitations carried over to the lenses as well. The initial 4 lenses for the Leicaflex were a 35mm f/2.8 Elmarit, a 50mm f/2 Summicron, a 90mm f/2.8 Elmarit, and a 135mm f/2.8mm Elmarit. I own both the 50mm f/2 and the 90mm f/2.8, and while both lenses are extremely sharp, built like tanks in their own rights, and capable of incredible renders in black and white and color, Leica was too restrictive in its SLR focal length and aperture offerings compared to contemporaries – in this case both German and Japanese – who offered proper high speed lenses and both super wide angle and super telephoto lenses.

Leica did follow up with the relatively rare 21mm f/3.4 Super-Angulon, but it literally only worked on one model – the Leicaflex Standard – due to the Standard’s mirror lock-up feature. As mentioned earlier, this does not do much to quiet the shutter sound. It would not be until the introduction of the Leicaflex SL in 1968 that super telephotos and properly fast optics would arrive for the Leicaflex, but the initial limitations on available optics did not help the Leicaflex’s cause in being perceived as a professional tool.

Overbuilt at the expense of adaptability

Adaptability worked against the Leicaflex too in the 1960s pro market. Whereas Nikon had innovated with interchangeable backs, interchangeable prisms (metered, non-metered, TTL metered), and motordrives, the Leicaflex Standard solely had lenses. Leica believed that modularity would reduce the strength and rigidity of the Leicaflex, but the market spoke; professionals and enthusiasts went for the more modular Japanese cameras over the more robust, but less user-friendly, Leicaflex.

While subsequent Leicaflexes (the SL and SL2) would offer TTL metering and special motorized models demarcated with “MOT” in their names for “Motor Drive Capable,” this lack of adaptability, combined with high price and limited user-friendliness relegated the Leicaflex to the back burner. There were no backs, no interchangeable viewfinders, nor were all models motor-capable. The sole exception were the MOT models, which had a different ground glass that could be fitted at expense for an end-user, but did not come standard in any way on non-MOT models. Leica’s limiting behavior towards the Leicaflex Standard severely hindered its viability in the 1960s pro market, and was a significant factor in Leica ultimately joining forces with Minolta in 1971 in a relationship that would last for the next quarter-century.

…And became a bargain in the 2010s market

So, having read how the Leicaflex was a catastrophic failure in the 1960s and its successors could not undo these failures in the 1970s, why then do I hold the Leicaflex as such a great Leica to have in the 2010s market. The answer is cost. Leicas have a serious cachet in the photography world, and while other models that were derided in their time such as the Leica M5 (1971-1974, 1994) have recovered in price, the Leicaflex has not.

It is completely possible to buy a Leicaflex for under $200, a 50mm Summicron-R for $250 to $400, and have a fully serviceable Leica system for under $600. Bearing in mind that these Leicaflexes were supposed to be the flagship model to put the M-series to pasture, and it looks to be a serious bargain. In addition, Leicaflex successors, barring the SL2 (insanely great meter, fairly rare), and the R8 and R9 (age, first non-Minolta based SLRs since the SL2) have also been relatively reasonably priced, although be wary of fast lenses and more recent lenses which may carry a significant premium.

My Leicaflex Standard wears a 90mm f/2.8 Elmarit Mk1, and while f/2.8 is the realm of professional zooms and f/2 and faster is the realm of short-telephoto lenses, the Elmarit was $250; going for a 90mm f/2 Summicron Mk1 from the early 1970s would have been $700. Is tripling the price worth one extra f/stop? That’s for you to decide; for me, the answer was no.

An excellent, but dead optical system

In addition, the Leicaflex is a bargain in the 2010s market because the R-Mount as it stands is a dead camera system. That means no new lenses are being made by Leica nor third-party manufacturers such as Zeiss, Sigma, or even Lomography. Whatever lenses are out in the world now are most likely all of the ones that will ever exist unless Leica decides to release an R10. Imagine, 270 degree focal ring throws, smooth as silk focusing with a finger, and that “Leica signature” that brings out the best in films such as Portra, Delta, and Pan F, without having to sell a kidney or your firstborn. This part (low lens cost due to dead-system) may be fading though; Cine users have begun discovering the capabilities of old Leica R glass and begun Leitaxing (changing the mount) to accommodate Cine use. There is a possibility of Leica R glass recovering at the expense of Leica R bodies, so try to build a good kit while you still can.

Systemic compatibility… to a point

Lastly, the Leicaflex’s operational limitations makes it a fairly inexpensive way to get into Leica. Unlike the M line where most lenses are compatible with any M (barring collapsibles and some specialty lenses with the M5), The Leicaflex only uses 1-cam lenses, which means that the expensive ROM lenses for the R8 / R9 (and compatible with the R3 – R7), and even more modern and possibly exotic 2-cam and 3-cam lenses from the 1970s through 1980s have extraneous parts not needed for the Leicaflex (more cams that pertain to metering).

The Leicaflex gives you a 1-cam requirement that puts all the metering requirements on you, the photographer. And while it may seem crude next to an R9, or even an SL, shoot it, use it, love it. You’ll lose the ability to automate, the ability to shoot aimlessly for Instagram, but you’ll gain an insight into how photography and light work that’s only rivalled by a completely meterless camera. In doing so you’ll become a better photographer as well, able to use light as you wish, and transfer that skill to any camera that may cross your path in the future. I love mine, and it has taught me immeasurably when to trust the meter, and when I should go at it alone.

Care and Maintenance

There are a few things about the Leicaflex that need to be addressed before buying one and pressing it into service. They’re minor, and thankfully won’t make a Leicaflex excessive to own and operate. While they are German and lacking much of the electronics of modern digital cameras, they are still German and that means they can be very complex to work on. Here’s a few tips

-

Buy from a RELIABLE dealer and get a report on its health. My Leicaflex Standard was a one-owner (along with its 90mm lens) and had full papers. Make sure you get a warranty and enough time to shoot and develop a test roll of film. Something basic like Tri-X 400 or Portra 400 will work.

-

Find a reliable tech to work on your Leicaflex. I prefer Don Goldberg at www.dagcamera.com for my Leicaflexes and lenses. While they may lack the tech of modern cameras, they have extremely complex internals that are not for the faint of heart.

-

Whereas the M-series, and the Leica Thread Mount have had their prices for bodies, lenses, and accessories increase greatly, the R-line, barring the R8, R9, and SL2 has largely avoided price growth. Lenses though are beginning to appreciate in value due to newfound use in cine applications, so get lenses while you still can.

-

A good Leicaflex Standard should be $200 to $300 for a body; a lens can be $250 to $500 for a good 50mm Summicron-I or 90mm Elmarit-I for the historically correct look. Avoid R-Cam ONLY and avoid ROM lenses, as there will be damage to either the body or the lens if mounting is attempted.

-

Grow some neck and arm muscles… seriously, the body and 90mm lens combined are over 1.5kg, and enjoy camera tank warfare!

Thanks to Hamish for letting me publish this post on 35mmc. If you’d like to see my photography, please feel free to go to www.flickr.com/ganzonomy. If you really like my work, feel free to subscribe to my Flickr as well!

Share this post:

Comments

Terry B on Leicaflex Standard Review – by Jason S. Ganz

Comment posted: 29/03/2018

"The Leicaflex only uses 1-cam lenses, which means that the expensive ROM lenses for the R8 / R9 (and compatible with the R3 – R7), and even more modern and possibly exotic 2-cam and 3-cam lenses from the 1970s through 1980s have extraneous parts not needed for the Leicaflex (more cams that pertain to metering)."

For clarity, for those not familiar with the R system, the cam issue can be perplexing, especially as they may be expecting all lenses to match every R body; lets exclude R8/R9 and their ROM lenses for this, but it does apply from the Leicaflex to R7.

Single cam lenses can be mounted on all bodies and whilst they permit full aperture metering in the Leicaflex, they will only permit stop down metering from the SL to R7.

Twin cam lenses, introduced with the SL, are backwards compatible with the Leicaflex for full aperture metering, and permit TTL full aperture metering from SL to R7 (I think) but not any auto exposure functions as found on the R3 to R7.

Triple cam lenses are fully backwards compatible to the Leicaflex and right up to the R7. "Fully compatible" simply means that they will couple with the metering capabilities of whatever body to which they are attached. These, then, are the most versatile, and expensive versions, but are the ones to go for if one owns a mix of earlier Leicaflex and later R bodies. And I'd suggest newbies to Leica reflex should consider these, even if buying a Leicaflex, SL or SL2, as they may wish subsequently to add an R body for its additional features.

As you point out, Jason, the build quality of the Leicaflex is superb and nothing coming out of Japan in that era is remotely comparable. And all the first series, single cam, lenses were rated as excellent performers in their own right.

Comment posted: 29/03/2018

Francesco Melis on Leicaflex Standard Review – by Jason S. Ganz

Comment posted: 29/03/2018

Kodachromeguy on Leicaflex Standard Review – by Jason S. Ganz

Comment posted: 29/03/2018

1968 prices:

M4 no lens $288

M2 no lens $214

M3 no lens $288

SL no lens $465

In 1968, I bought my first serious camera, a Nikkormat FTn with 50mm f/2 lens. It was $209 total.

In 1971, my wife bought a Pentax Spotmatic with 55mm f/1.8 lens (still in use!) for $195.

For a young photographer, the SL was out of reach price-wise. The Nikkormat and Spotmatic were not as well built, but the lenses were only marginally poorer than the Leitz ones. In fact, many people say the Takumar 55 f/1.8 is one of the best from that era.

Another big factor was the revaluation of the Deutschmark. From about 1960 to 1968, the DM was pegged at 4 to the US &. Then in mid-1969, the DM was revalued and moved down to 2.0 to the US $ by 1978. So all German manufactured products crept (jumped) up in price. Those were tough years for E. Leitz.

David Murray on Leicaflex Standard Review – by Jason S. Ganz

Comment posted: 09/09/2018

David Murray on Leicaflex Standard Review – by Jason S. Ganz

Comment posted: 12/09/2018

I now have 35/2.8 , 50/2 , 90/2.8 , 135/2.8, 250/4. The quality and build of this gear is absolutely amazing. It really has stood the test of time.

I'm really glad I've got this stuff and have sold off my Nikon F bodies and lenses.

Comment posted: 12/09/2018

Jim McLean on Leicaflex Standard Review – by Jason S. Ganz

Comment posted: 01/10/2018

Comment posted: 01/10/2018

Comment posted: 01/10/2018

5 Frames with a 35mm Curtagon Shift Lens – by Christian Schroeder - 35mmc on Leicaflex Standard Review – by Jason S. Ganz

Comment posted: 03/12/2019

Recommended reading : Down the Road on Leicaflex Standard Review – by Jason S. Ganz

Comment posted: 05/03/2020

Stefan Staudenmaier on Leicaflex Standard Review – by Jason S. Ganz

Comment posted: 04/04/2020

Till I heard some guys meantion the outstanding build quality.

Loving my Nikon F and Nikon F2 for just that perfect mechanical values

I reached out for a Leicaflex SL2 and was blown away.

Now I understand why they are still very pricey and hard to get.

But even a Leicaflex (1964) is near the level of perfection for 1/3 of the money

so I couldn’t resist and got one.

In combination with a Elmarit 2,8/135 this is a joy to use for portrait and street.

Like you mentioned the viewfinder is very bright and much better than any other

Camera I know from this area.

It is much more solid than the Nikons and Canons, by its bigger size also has more grip

than the Pentax Spotmatic.

The Takumar M42 are outstanding and build to the highest level anyone can imagine

and almost as small as Leicas M optics but I really prefer the R handling over all.

Enver Hoxha on Leicaflex Standard Review – by Jason S. Ganz

Comment posted: 01/09/2020

Toby Madrigal on Leicaflex Standard Review – by Jason S. Ganz

Comment posted: 06/12/2020

I’ve got a black chrome SL body, 1974, I’ve been using a PX625 1.5v Alkaline cell and tests with a Gossen Lunalite and Sekonic L-428 incident meter give the camera 1 stop underexposed readings. This is on a piece of sunlit grass with a 135mm f2.8 lens. I can check the condition of the battery using the little black button. Certainly good enough to use Ilford XP2 Super with tip-top latitude.

Wade Petrilak on Leicaflex Standard Review – by Jason S. Ganz

Comment posted: 27/05/2021

ogDavid Murray on Leicaflex Standard Review – by Jason S. Ganz

Comment posted: 19/04/2023

The feel of this 1964 camera gives me a great deal of pleasure. It’s like my Omega Speedmaster watch and my Mont-Blanc pens and pencils. The Billinghan 225 bag I carry my gear in 28/f2.8; 90/2.8 and 135mm f2.8 lenses all in. I do have a 2X converter and handheld meter to supplement the outfit.

The battery issue I ignore and simply use handheld-incident and reflection. This is what professional professionals used for decades.

Good enough for them, good enough for me.

Dan on Leicaflex Standard Review – by Jason S. Ganz

Comment posted: 08/05/2023

I also don’t read much about 100mm Elmar lens which has performed splendidly on both the ‘flex and adapted on a Sony a6300.

Toby Madrigal on Leicaflex Standard Review – by Jason S. Ganz

Comment posted: 21/07/2023

Chris A. on Leicaflex Standard Review – by Jason S. Ganz

Comment posted: 23/11/2023