A photo must ENGAGE THE VIEWER. This is one of my core beliefs about photography. A photo might have profound meaning or it might be throwing light on injustice or espousing some worthy cause but if it’s not a good shot then WHO CARES? Before anyone will care about an image it has to command attention. It’s not a manifesto they’re looking at – it’s a PHOTOGRAPH.

I have never been a professional photographer, but commercial photography is something that has earned me money over a long period of time, and was for a time my chief source of income. But it was never my only job and I never really saw it as a goal. It just sort of happened.

The idea of this article then, is to say how we can be better photographers by treating parts of it like a job.

I was quite dismissive of photography when I started learning it: it was nothing more than a tool. I was more interested in painting then. I used photography to record my artworks; to archive them. But this meant I needed to learn about things like white balance and metering and colour. I wanted to make photos of artworks that would look like the artworks. But if you go down that path (in the film age) you wind up learning about dynamic range of film, sharpness, resolution, depth of field, colour temperature. You learn to meter for tranny. You learn why incident metering is different from reflected metering and how film sees things differently from how your eyes do.

And then, because in those days it was way less common for people to have cameras – professional cameras anyway – I started picking up work shooting little bits and pieces for a couple of publications.

I was really just playing with things that interested me, light, colour, composition, but it turned in to something useful, and so I was making money out of it. I had quit my first (and last) full-time job at age 26, so making a bit of money from a hobby was always a good thing to do. It’s been pretty much my modus operandi since then actually.

Thirty years on, photography seems to have obsessed me as an art form and as something of a vocation, and so I just thought I’d share some ideas about how a dilettante such as myself – or how anyone for that matter – can benefit from doing commercial work.

It’s about the client.

In 1992 I did a photography course at a TAFE (Technical And Further Education) college and I had a really good teacher. (Bless you Tony Vas) In the first day of class he wrote on the whiteboard:

Commercial Photography: Producing photographs to clients’ expectations.

That really struck me. It’s not about you Dave, it’s about the client.

A client is not a bad thing. Sometimes people say, “Oh! I’m so glad to be an amateur!” I shoot only to please myself! Nothing gets between me and the purity of my vision!”

I mean no disrespect to this view by the way. It’s a fine view – In fact I think it was reading a nice article here on 35mmc along those lines that got me to crystallise the views I’m expressing here.

Where the view can be expanded though, is that everyone who is showing their work to others – i.e. anyone with an Insta account or posting on fb – is engaging with an audience. And the audience may not be your only concern or even your primary concern, but surely it must be a factor.

If you think of your audience as a CLIENT, then it helps put your work in perspective. The audience might be your family if it’s Christmas snaps, or your friends if it’s shots of your dog, or the people in the online photography group you post to. But view them as a client. They are not giving you money, but they are offering you some of their time in looking at your photos. What does the CLIENT want? Do they want 12 shots of your dog being cute? NO THEY DO NOT. Hey, it’s a super-cute dog but one shot will do. Why send them all seven shots of grandma with the kids? How about we think about it first and not send those ones where grandma has her eyes rolled back and looks like she’s having a stroke. Likewise that koala you saw in that tree yesterday. If you took 25 shots of that koala do you really need to share them ALL with the world?

These examples might seem a bit extreme or silly, but let’s put it this way:

OK – you’re an amateur, you are doing this purely for fun; to please yourself, but you should consider your audience. It’s out of respect for them. Respect their time. You owe it to them to edit, to consider what you are showing and why. Is every piece you send out the very best it can be? You also owe it to yourself, because it will make you a better photographer.

“Hi Dave. Thanks for that help you gave me with how to use my camera. I’d love you to look at my holiday photos and tell me what you think – here’s a link to my Google drive with the shots. There’s about 150, so they’re not all great because I have not edited them.” A dear friend actually said that to me.

Treat your audience with the respect you’d treat an important client.

You are not the work and the work is not you.

This is probably the most important thing of all. You are a person. You are not your photos. If your photos are crap it does not mean you are a crap person. If someone does not like your shots it does not reflect on you.

Distance yourself from the work a bit. A failure of the work is not a personal failure.

I have observed that this is what people seem to worry about the most; they worry whether the work is good enough and they worry what people will think about them because of it. They become afraid. And then the fear that their work is not good enough translates to a fear that THEY are not good enough. The fear stops them from exhibiting publicly and thus learning all the things they can from that experience.

You have to stand back from the work and try to be objective. You have to view taking photos like taking on a job. Are you going to do it or not? If you are, then get on with it.

Imagine your job is fitting tyres on cars:

“Hi – could you fit some tyres on my car please?”

“Well, I don’t know. I mean, fitting tyres on cars is something I’ve always been passionate about, and yeah, it’s very personal. When no one understood me as a teenager I think it was fitting tyres that really saved me; you know? I mean it got me through some dark times, but fitting tyres – now? On your car? Yeah look I’m not really so sure about how I feel about doing that.”

Are you going to take the job or not? Just fit the tyres. Or don’t.

Please understand I mean no disrespect to those people who might genuinely be struggling and held back with anxiety. I guess I’m saying that there has to be some risk involved in the process. If you’re sure of your work then what are you going to learn from it? There must be uncertainty. There must be risk. I’m certainly very unsure of my own work.

It comes back to distance a bit. You might need to stand up at a gallery opening or give an interview and talk about your work. It might not be what you like doing, but you need to do the best you can at it. These things will be uncomfortable but they need to be done. Remember – it’s not about you; in this context you need to quiet the discomfort and get on with it. It’s about the WORK.

It’s worth practising. My daughters are both doing post-grad and they have thing called the the “Three minute thesis” where they learn to explain their complex three-year PhD thesis in the three-minute powerpoint. Another one is the “elevator talk” where you imagine you’re describing your work in 30 seconds to someone standing next to you in the lift.

It’s picking up skills

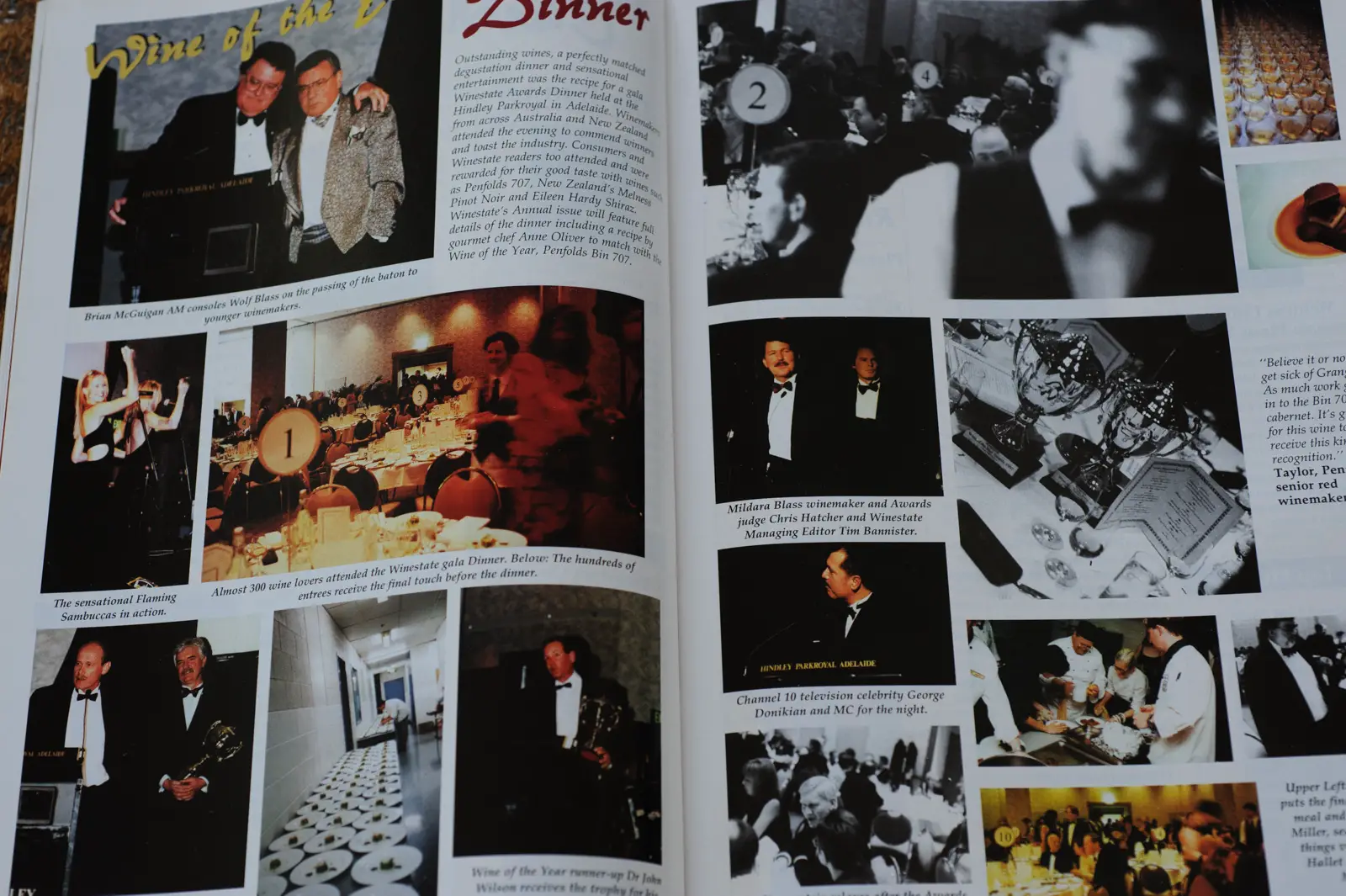

Once a year I would have to shoot the awards dinner for the magazine that was my main client. I really didn’t like doing it, but I had to. I got to stay in a nice hotel and drink expensive wines so it wasn’t too bad, but yeah – it was event photography and I hadn’t set out to do that.

I didn’t like doing it back then – it made me uncomfortable. But I got better at it and it has given me skills I’m now glad I have. They are skills I can use in the photography that I now do for pleasure. And a lot are just general life skills as well.

I was at a gallery opening recently and a group of friends were having a show: “Dave! Quick – you’ve got a camera – we need a group shot!” Of course you do. The light here is shit, I’ve got my little camera with a standard prime, no flash and you guys are on the other side of a trestle table, all fizzing with excitement and we have to get this done in 30 seconds. Oh, and because you’re all photographers it had better work – OK?

I got an acceptable shot. Please understand that I’m not saying, “Oh – I have some sort of special talent; I’m so good.” I’m saying that when you work at things you learn from that and get better at them. You become skilled. And you can use those skills to do other stuff that you never thought you would.

And it sharpens you up. If you’re shooting a dinner or a wedding or an awards night you have a responsibility to your subjects and to the people you’re shooting for. You need to bring back the shots and not screw it up, so you need to know what you’re doing. This kind of behind-the-scenes work is a partnership between you and the subject. You’re helping them and they are helping you. I thought it was a great privilege to see what commercial kitchens were like, or what the insides of wineries were like. It’s a bit like you have an access-all-areas pass to places you would otherwise not get to see.

It’s bending the rules, making shit up and pitching the idea

I almost get a bit sad when I see people setting themselves up as commercial photographers and they have a website and they put a portfolio up with an engagement shoot and a baby-bump on the beach at dusk shoot and all the shots have some warm brown LR preset thrown over them that looks the same as every other website, and they write some fluff about how they love creating unique moments that last forever and I think, “BUT WHO ARE YOU REALLY? I’m sure you’re a much more interesting person than this.”

I can’t see the point in doing something that someone else is doing only doing it worse. You can steal styles as a learning tool for sure, but don’t forget to look for your own voice.

When I was shooting with one camera and one lens, did not own a flash, had no access to a studio or anything – I realised I had a choice: either I don’t take on the job, or I invent some way of doing it with what I have. That sort of became my voice; Making Shit Up. (Or maybe we can call it Problem Solving)

When I started, I developed my own style. I don’t know if I realised it at the time but looking back now it was:

- Natural light (because it’s all I had)

- Shallow depth of field (because I’m shooting wide open to try to get enough of said light)

- Using light, colour and composition (because I like that sort of stuff)

- Pinching ideas from contemporary art (because I thought those ideas were cool)

You also need to pitch an idea – to sell an idea to an editor. If there’s something you want to try, or something you think is worthwhile, you need to justify it.

This is a really good skill to pick up when it comes to clarifying your own intent or examining your motives. If you’re explaining your work or ideas to someone else who’s critical, that’s good practice. Your imaginary editor is a good sounding-board.

“Hey, I’d like to shoot this like…” You say.

“Why?” They ask.

“I’m doing this because…” An imaginary conversation with your imaginary editor can help sharpen up your intent.

It’s not about gear, it’s about doing the work

Gear doesn’t matter; it’s about getting the most out of your gear. If you look at how the greats work they don’t often change cameras or try new lenses or different films in their work (of course you can quote me as many exceptions as you fancy).

And here is where the internet lies to you – because the on internet it’s ALL about gear. And I’m as bad as anyone – I have GAS and way too many cameras. I love it, but I know it does not help my work. In fact I’m starting to pull back now because it’s actually hurting my work to play with new cameras if it means I might lose familiarity with my trusted ones (Trusted two or three, that would be)

I think I’m getting better at buying a camera because I want it, and not thinking I need to justify that by using it. Buying film cameras wisely need not cost you money if you buy well. If you have a bit of money sitting in the bank, parking it in cameras is not too silly if that’s something you enjoy.

And how on earth does this help me, or you, or anyone?

I think I’ve learned that it’s work. Shooting a moody dawn seascape might seem a world apart from shooting the inside of a commercial kitchen, but there are things I learned while working that carry over.

You need to make the effort and turn up. Sunrise happens on time. It won’t wait if you want to have a sleep-in. I used to smile when I’d see a person with their Blad walking around Venice at 10 in the morning when they’d missed the light by three hours.

You need to be totally committed. You’re not here for a chat, or to have coffee. You’re here for the shot. If the shot is not the most important thing at this moment then pack up and go home. Why did you bother turning up in the first place? If you’re here because you want to look cool and walk about with a brassed M4, that’s fine, but if you’re looking for images you need to be totally focussed on that (OK – hard to avoid the pun) My family is used to this by now; I hope we’ve established that if we’re walking down to San Marco before dawn I’m going to be concentrating on what’s happening, not making chit chat. If we’re staying at the beach I’ll be looking out of the window an hour before sunrise to see what the sky is like. My wife knows by now that her coffee won’t be served until the best light is gone.

It’s striving for an eye

Here’s where I’ll try to wrap it up, and here’s where it gets tricky and where I can sound (even more) like a curmudgeon, but this is what I believe. If I did not say this I would not be honest.

“Be guided by taste, it is rare.” That’s the advice that Cezanne gave in a letter to Emile Bernard, so I’m abdicating responsibility a bit by stealing from him, but I totally agree.

Developing an eye – an aesthetic – is really tough, and I say this with all the honesty I can; most of the stuff you will see on the internet, on 35mmc, or any other website (and I certainly include my own) is no good. And before burning me for saying that; let me explain what I mean. I’m not talking about doing something for fun, I’m talking about trying to develop an eye that can differentiate between ordinary work and the work of a great photographer and then striving for those standards yourself.

It can be confusing – because there’s a whole lot of noise out there. With the best of intentions, people are pedalling crap. “Hey – shot my first roll of 120 and loving the tones I’m getting from my 7ii with Portra 800 pushed.” “Man – those are awesome; talent!” I’m sorry, but the shots are not that good and you don’t understand the nuance of what scanning can do and if we examine this a bit further we find you don’t know what pushed means either. But there is the cacophony of misinformation that supports itself. There are cool YouTubers with a trillion views who make content that is really entertaining and very cool but it’s not really about photography. And they are not photographers – they are YouTubers who own cameras.

On the other hand also on YouTube there are wonderful docos about the great photographers. I still get a bit of a feeling of vertigo when I discover a great photographer that I was unaware of. Most recently it was John Deakin who worked in London in the 50s. It was a really physical shock seeing that work; and it’s a really good way that I can use to keep perspective amid the noise of fb and Insta. Just looking at his work and having a physical reaction to its quality is such a good reminder that work CAN be that good. And when people say. “Oh, it’s just an opinion. My opinion of what’s good is just as valid as anyone’s” I have to keep quiet because I’m afraid I don’t agree and if you think that, well I doubt I’ll be changing your opinion so I’ll just try not to offend you. Please understand I’m not trying to put anyone down here, but I do believe that some work is better than other work. I’t’s not all equal. Deciding where I stand on aesthetics has been a very long process and it’s an ongoing one. I still side largely with Plato and think Heidegger went a bit far, but there you go. It was delicious comparing Deakin with Bailey, looking at influences and considering what each brought to the table. It’s a great pleasure, but I also find it a very serious and difficult pleasure.

I love meeting people who have a better eye than mine and I love seeing work that is better than I can make. It is a joy and it delights me to this day. So how do you get an eye? This is a never-ending story in itself, but as a start I would say you have to just love looking at images and be really affected by them and spend ages trying to work out why some are great.

I remember – before I was even interested in becoming a photographer – being blown away by David Bailey’s “Goodbye Baby and Amen.” I just stared and stared for hours. And when I discovered Cartier-Bresson I just thought, “That’s it. Why does anyone even bother taking photos any more? No one can touch this guy.” And the more I studied, the more great photographers I found.

There’s Avedon, Nan Goldin, Bill Brandt, William Klein. I could name 50 before leaving the top echelon. But anyway – of the six I just named, five were commercial snappers. It’s not all ivory towers and Soho galleries.

Applying the discipline of the commercial photographer is part of the process. It won’t get you there, but it’s an arrow in the quiver. It helps get the mundane skill stuff out of the way so you can use your voice better.

Happy photography all.

Share this post:

Comments

Chris on Why Taking Photos for Money is Good for You – By David Hume

Comment posted: 28/05/2021

I really appreciate your perspective and the strength of your conviction. It’s refreshing. I think you make many good points and I’ll certainly be looking at my own work with a more critical eye - keeping it fun (which is why I do it) but also recognising that a bit more rigour might add something missing and meaningful as well.

Thank you for the article!

David Hume on Why Taking Photos for Money is Good for You – By David Hume

Comment posted: 28/05/2021

With best wishes for you and your work.

Bill Brown on Why Taking Photos for Money is Good for You – By David Hume

Comment posted: 28/05/2021

I've been a photo retoucher since 1976 and self employed since 1982. Believe me, to do this at the top of your game requires a total commitment to someone else's ideals. That's not to say I don't mix in much of myself but the final result MUST make the client happy if you want repeat work.

I've now amassed a film archive spanning more than 50 years and I consider my recent work as some of my best. Even though I'm shooting for myself I feel all that experience from past decades and projects all comes into play at the moment I press the shutter release. I'm just an avid enthusiast but that hasn't stopped me from working to obtain the best possible result at any given moment. Life rarely provides second chances.

I've gotten some great shots from time to time but it mean't making the effort to put the subject in front of my camera. I feel that my life has been extra blessed because of the places my camera has taken me. Places that I wouldn't have gone otherwise and into situations that I personally would not have walked into. Looking back over these experiences I realize I'm a different person because of those moments.

I'm rambling on so I'll stop. Thanks for saying what needs to be said. If you're going to spend all the money and time on shooting film why not make it the best it can be. I started my career working with the photographer Bank Langmore. He showed me that excellence is not something we hope to occasionally achieve but is a way of thinking and living. My whole professional life has been built on that idea and I will be forever grateful to him for setting that foundation in me.

Thanks for showing some tough love. When the emperor isn't wearing any clothes someone needs to let him know.

Comment posted: 28/05/2021

Ken Rowin on Why Taking Photos for Money is Good for You – By David Hume

Comment posted: 28/05/2021

Comment posted: 28/05/2021

Leonardo Mosquera on Why Taking Photos for Money is Good for You – By David Hume

Comment posted: 28/05/2021

Regarding photography affording access, let me go on a tangent and quote Roger Ebert on a review of End of Watch:

"From a dramatic viewpoint, there are few professions that grant their members entry into other lives, high among them cops, doctors, clergymen, journalists and prostitutes. Perhaps that explains why they figure in so much television and cinema. Their lives are lived in the midst of human drama."

To that list, I would add photography in general; particularly photojournalism but also sometimes documentary and even commercial photography, like you expressed here.

Also one very specific question: what does "meter for tranny" mean? In this case, Google is uhh... not my friend.

Comment posted: 28/05/2021

Leonardo Mosquera on Why Taking Photos for Money is Good for You – By David Hume

Comment posted: 28/05/2021

Brian Nicholls on Why Taking Photos for Money is Good for You – By David Hume

Comment posted: 29/05/2021

A veritable wellspring of wisdom!! The 'twelve shots of the cute dog, and twenty four of the koala' has struck a chord with me for which I plead guilty, and in mitigation can now say I am now the richer. Thanks for the nudge!

Comment posted: 29/05/2021

Sroyon on Why Taking Photos for Money is Good for You – By David Hume

Comment posted: 30/05/2021

I must admit I came to the article expecting to stumble upon points of disagreement, but I think by and large I agree with what you say. Well maybe I'd add a few qualifiers here and there, but hey, then I should write my own article, right? Haha. For example, I have a grudging respect for the respect for the YouTubers you mention, especially the ones who are able to grow their channels to tens of thousands of subscribers. The photography is often nothing to write home about, and I do sometimes get tired of the misinformation, hyperbole, etc., but in their own way – in their choice of topics, how they present themselves, video production values – it seems they are thinking about the client. But as you say, that makes them good YouTubers, not necessarily good photographers. And watching the videos won't necessarily makes us good photographers either.

I don't share much on social media (for example my IG has one post last month, none this month) but I often show my pictures – sometimes prints, more often via WhatsApp – to friends and family. Very few of them are photographers – most don't even own a camera other than the one on their phone – and it's refreshing to see how little they care about whether a photo was taken on film or digital, what kind of lens was used, things like that. They like the picture or they don't. It keeps me honest, I think :)

In a way it's easy for me to agree with much of what you say, because deep down I think I'm a people-pleaser. Social media likes don't motivate as much (see above), but few things give me greater joy than when someone asks me to take pictures at their wedding, for example, or with their kids. One of the great joys of being a photographer, even for a hobbyist like myself.

David Hume on Why Taking Photos for Money is Good for You – By David Hume

Comment posted: 30/05/2021

Michael B. on Why Taking Photos for Money is Good for You – By David Hume

Comment posted: 03/06/2021

Comment posted: 03/06/2021