I’m writing this because expired film generates a fair bit of internet interest and chatter. It’s also something with which I have reasonable experience and I’ve formed my own ideas based on how it has been useful for me.

The idea of shooting expired film seems to polarize people; and I can understand that. I’m a bit of an analogue grandpa myself and I fully empathise when film natives do the eye-roll and shrug at others going wild over expired film stocks when they’ve not yet engaged fully with fresh ones.

On the other hand I have learned a tremendous amount from shooting expired film stocks. In fact, some of my most successful images over the past five years were shot on badly stored 20 year old stocks that really had no business being put through a camera.

I’m a visual artist who uses photography, and I’m also a big believer in the adage, “If you can’t explain something simply, it means you don’t understand it,” so what I’m aiming for here is to give clear illustrated examples from some of the rolls of expired film I’ve shot, HOW it was shot and digitised, what I got out of that, and WHY it was valuable to me.

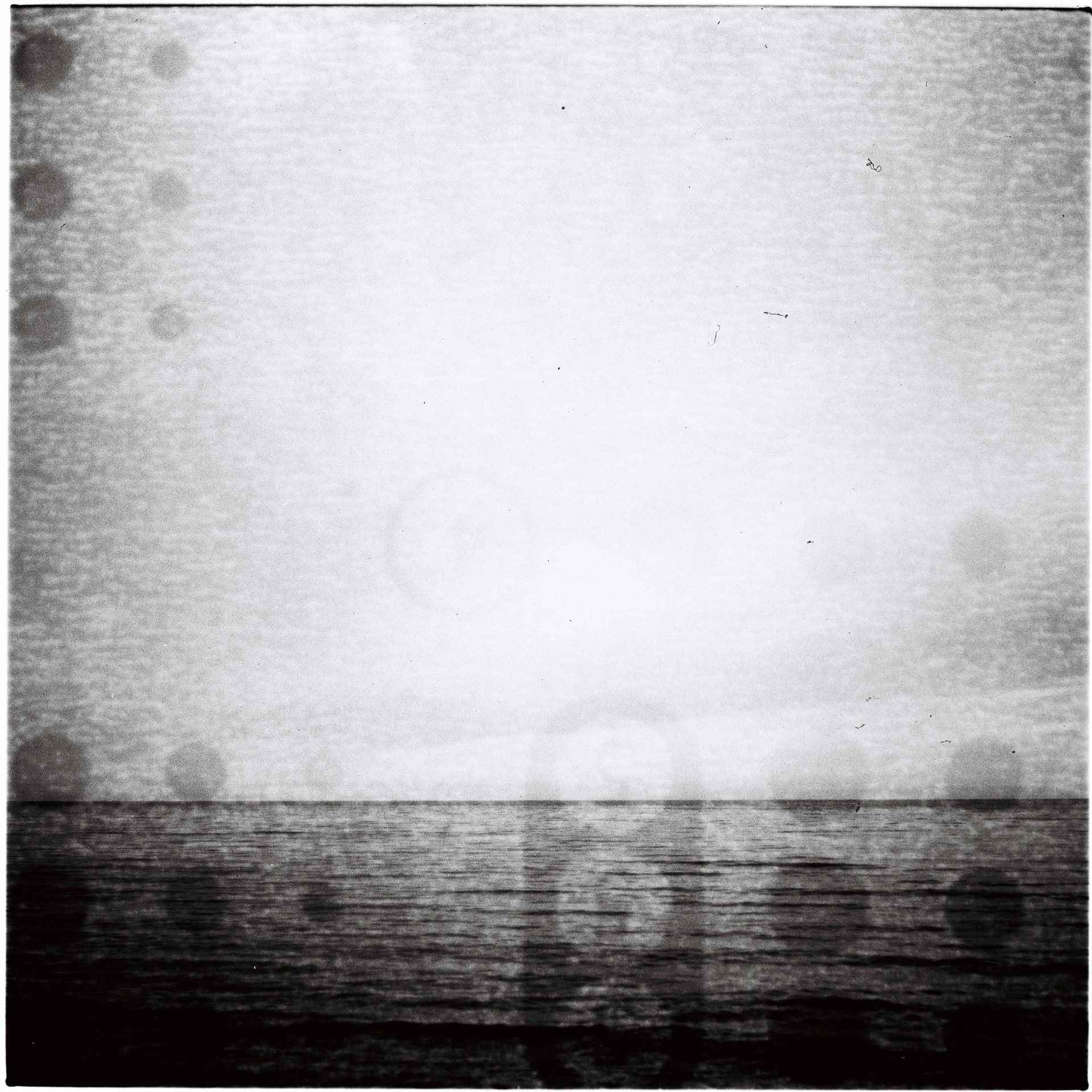

Roll 1: On The Beach.

For me it all began in 2018 with a roll of 30 year old B+W film (FP4 in 120 format) that I found in my studio. It had been baking in the heat of 30 Australian summers and I really had no idea what would happen when I shot it. I expected nothing, but thought I would see what came of it. Sure enough, when I picked the film up from the lab it looked like little lumps of coal were sitting on acetate. “Oh well, that’s that then!” I said to the lab guy. “But wait,” he said. “Don’t you want so see what I’ve pulled off it?” (Clearly he had gone above and beyond in trying to salvage something from the roll.) Sure enough – something was there.

Now; here comes the bit where the whole thing became useful for me. These frames were not good at showing the scene, but they were very useful to me in saying something about the nature of photography.

The purpose of these frames is not to show the sea, but to say to the viewer, “This is not the sea. You are looking a photograph.” I made this even more obvious by printing out some frames on acetate sheet and covering that with RubyLith masking film and then re-photographing them (see feature image.) They then became part of this larger work.

This work formed the backbone of two exhibitions – so it was useful. Could I have done it on fresh film? No. Digital? No.

So – was this film faulty? Of course. Did it give me a special character that I could not get any other way? Yes. It gave me an unexpected result that allowed me to place other work into context and spawned other ideas.

Take-home lesson. I thought there was nothing on these frames, but there was something. These frames enabled me to make work that said, “You are not looking at the sea here – you are looking at a PHOTOGRAPH of the sea.” I wanted to highlight that the photograph was an object in itself, not a representation of its subject.

Tech Tips. I gave the film two extra stops of exposure and had it processed normally. If I’d been scanning it myself I’d have given up, but the scanning guy (Andy at B+W for any Adelaide people reading) went above and beyond and showed me stuff I was later able to use.

Roll 2: Dirty Fruit.

That first roll got me to thinking… These were early Covid days, so travel was not a thing, and I was mucking round making still life at home. I returned to an old project about the close observation of domestic objects. In this case it was fruit. This was based on the work of the painter Paul Cezanne, who in his Proto-Cubist work was very much into close observation; the idea that it was important to really study every object, every scene as closely as possible.

Because I’d recently shot some of the crappy new SX70 Polaroid film, this expired film had got me thinking so I asked around, and a friend gave me a whole shoebox of various expired films; 135 and 120, colour neg and transparency, mostly around 20 years old and never fridge stored. (Bless you Gee, I didn’t realise at the time that people actually BUY old expired film.)

And so the fun began.

Let’s start with transparency (slide) film. It’s easiest to explain the theory of it with this, because what you see on the film is what you get; whereas with colour neg everything has to be reversed and there’s the also the orange base of the film to take into account. But the principles are the same (more or less – don’t flame me here with the differences between C41 and E6; we’ll get to that.)

I’m also writing this article partly in response to things I see in online discussions where people post their scans and go, “Help! What’s wrong with my film?” First things first: to work this out you need to see the film, not the scan. A bad scan just tells you you’ve got a bad scan; to judge the film you need to eyeball that film and know what to look for, which is way easier with transparency than with neg.

Here’s a pomegranate shot on Agfa Prescia 100 (slide film) that was about 20 years expired.

Now, if someone posted this on a forum and said “what’s wrong?” the first question to ask would be, “Well, what does the film look like? Is it the film or the scan?” And this applies whether it’s negative or positive film – but with positive it’s way easier to tell, because you’re looking right at it. Yep – this is what the film looks like, which you can’t easily judge from a colour neg.

Below is what I made out of that scan. It’s something pleasing to me. Is there any point in actually doing this though? Would I have been better off just using fresh film or digital? Well, no. I actually tried it on this very same set-up and it didn’t work for me. The whole process felt forced and unnatural. It’s a bit like how I feel when I add film grain effects to a digital photo. It is fake, and I never find the results satisfying.

Here’s how this work ended up.

Roll 3: Trees in the mist.

Any time we make a photo we are acting as a conduit between the world and the photographic process. Film or a digital sensor has a certain range of things it can and can’t record and we need to be sensitive to that.

I knew my expired transparency films had reduced dynamic range and so looked for a low contrast scene for the next film outing. There was a hill near my house where I had seen some lovely low cloud rolling up, and on one promising morning I headed up there with a roll of Fuji Provia 400D (RHP) again about 20yrs out of date.

I did not have to do much with this – I just increased the contrast and got the colour back to where I wanted it. I really like this shot. I did not ever use it because I only got two shots from that day and roll that were good.

And that brings up a good point; another thing about expired film is that if you only have a roll or so from the same batch, you never know what you’ll get, and it makes it hard to shoot a project.

Segue to the next roll:

Roll 4: Christmas.

I’m not a huge fan of expired colour negative I have to say. To my way of thinking with colour neg the expired factor does not give you so much. If you have a good colour neg roll you can easily reduce contrast – crush the shadows, reduce the saturation, dynamic range or whatever. In other words, you can take things OUT of a good roll if you want to, but you can’t put things back IN to a bad roll. Of course this applies to a degree with transparency but for me the transparency is more interesting, quicker, and more educative.

I had lots of colour neg in my shoebox and quickly worked out that the Portra there was partly OK, but did not give me anything that fresh Portra didn’t and the other amateur film was so crap by that time I’d shot it there was nothing much to be seen.

The exception was five rolls of Fuji Press 800. Firstly, this is an interesting stock, and I really wanted to see what the grain would be like after 20 yrs. Secondly – if I liked it, the remaining four rolls would be enough for a project.

So I rated this roll at ISO 160 for 20 yrs out of date and away I went. I had in mind that it might be good for a nostalgic people project so I shot this roll on Christmas day. Christmases are great because they quickly become historical records.

The shots were legible, but not great by any means. I used them to see what would happen if I made a virtue of their weaknesses. The base of the film had gone a murky amber, shadows were blocky and the grain was pretty massive. I took my shop scans and in sympathy with this I further crushed the shadows to black, reduced detail, went heavy-handed on the colour. I still have not thought of a project for the other rolls though; revisiting them for this story I did like them more than I expected. We’ll see where it goes.

Tech Notes:

I should also state that all these transparencies were shop processed and I digitised them myself. I started doing this back in 2009 with a Nikon D700 and a Nikkor Micro lens (the 60mm f 2.8 AFD) All I did in those days was take a custom White Balance off my lightbox and go from there. In those days it was mostly Velvia 50 in 120 that I had, and I noticed even then that there was often a whole bunch of detail in the shadows that I had been unaware of but that you could bring out with a bit of work on the curves.

The colour neg was shop processed and I generally scanned it on a flatbed, but the two neg rolls here were shop scanned then worked on by me. I occasionally digitise my negs with a camera on a lightbox using NegLab Pro; I usually just leave my negs as shop scans though. I’ve been using the same place that has SP-3000s for a few years and I like the consistency. Another thing about expired negative film is that that unless you’re dev and scanning yourself it’s still expensive, so it makes less sense than E6 where you can look at the transparencies and work out if it’s worth the bother to scan them.

Summing Up:

So there you have it. This for me was very beneficial. To date I guess I’ve shot 1-2 dozen expired rolls of which four were used for commercial and exhibition work. As well as this, the process was very educational, and shooting this film has informed my views on shooting any kind of medium, be it film or digital. It highlights how the things that we might take as absolutes are actually not. The capabilities of film and sensors are just a small subset of the ways light sensitive materials can be used to make images, and it’s good to be reminded of that. It’s good to be challenged and interrogate what we regard as a good image, and why we think that, and see if perhaps there are not other ways we can consider and expand our image making.

I hope this has been useful; thanks for reading!

Share this post:

Comments

Geoff Chaplin on Expired Film – My Hows and Whys

Comment posted: 28/05/2024

Comment posted: 28/05/2024

Steviemac on Expired Film – My Hows and Whys

Comment posted: 28/05/2024

Your article however gave me pause for thought. I liked the notion that the photograph itself is the result and that a faithful rendition isn't necessarily the desired outcome, rather it's a 'lucky dip' of what you might get. I have some decent quality expired film from circa 2005 which has been fridge stored throughout. I was going to sell it, but your article has inspired me to try it out simply as an experiment to see what I get, rather than to record accurately what I see.

Comment posted: 28/05/2024

Mark Ellerby on Expired Film – My Hows and Whys

Comment posted: 28/05/2024

You have some pretty colours in yours. Is it because it's slide film do you think?

Comment posted: 28/05/2024

Julian Tanase on Expired Film – My Hows and Whys

Comment posted: 28/05/2024

Thank you !

Comment posted: 28/05/2024

Gary Smith on Expired Film – My Hows and Whys

Comment posted: 28/05/2024

Comment posted: 28/05/2024

Greg Hammond on Expired Film – My Hows and Whys

Comment posted: 28/05/2024

Comment posted: 28/05/2024

James on Expired Film – My Hows and Whys

Comment posted: 28/05/2024

Comment posted: 28/05/2024

jol on Expired Film – My Hows and Whys

Comment posted: 04/06/2024

Comment posted: 04/06/2024