The Olympus Trip 35 is a compact 35mm viewfinder camera released in the late 1960s that sold millions of units and had a long production run. It’s a famous benchmark camera for sure. (A look at the Olympus website is instructive here.)

It was a pretty basic camera in the Olympus lineup and came out after the Pen EES of 1962 that shared the electronic exposure system and before the more advanced Olympus 35DC compact of 1971 (that needed a battery) and the OM-1 of 1972. Obviously it was spot-on for the time it was made – its sales success attests to that.

Today the situation is different. This is a camera that was designed to produce great holiday snaps and be easy to use. It was superseded though, by a style of camera that also produced great holiday snaps and was even easier to use. An obvious example would be Olympus’s own AFL from 1984 or Mju from 1991; cameras with auto focus, built in flash, auto wind, auto load; all that stuff. So there was a time when Trip 35s were plentiful and a bit obsolete, and as such could be picked up for a song. But what’s the story as we move into the 2020s?

First thoughts.

As anyone who reads 35mmc would know, the electronic point-and-shoots that edged out the Trip 35 and which were themselves so cheap on the used market that they were almost disposable are now much more expensive. As well as being expensive they’re fragile, as their now-aging electronic internals get flaky and they brick up with no hope of repair. As a new generation of shooters coming to film from a digital upbringing cast their eyes around for usable cameras, the Trip 35 has every right to be reexamined.

Let’s take a look.

It’s light but made of metal. It sits well in the hand. Its silver satin finish is really nice and the controls are smooth. Some bits are plastic, but the bits that matter work really nicely. The focus is well-damped and smooth and the aperture, focus and ASA rings are all machined metal. It’s the sort of camera that looks better the closer you look. I think it’s a good looking, classy unit. And it’s not pretending to be anything it’s not; it looks 60s cool because that’s when it was designed, not because it’s being nostalgic.

Operation

The Trip 35 occupies the interesting position of being auto-exposure but having no batteries. The small amount of electricity it needs to work its light meter and control the shutter speed and aperture comes from selenium photo-voltaic cell around the lens. This means that there is no problem with unobtainable batteries or corroded battery compartments – as long as the selenium cell still works you’re in business. The cells appear to last well if they’ve been kept covered up by the lens cap, and the Trip 35 is a today pretty viable proposition. It’s easy to test if it works, and actually quite fun, as it also lets you see the aperture blades moving. If you look at the lens from the front, as you press the shutter release you’ll see the aperture blades opening and closing to the correct aperture. To test the shutter – with no film in it, open up the back, wind it on and look through the lens at a bright scene as you fire the shutter. If you see a little diamond shaped fleck of light the shutter has fired and you’re in business. If you cup your hand over the lens to block the light and try again you should get a red flag in the viewfinder and no shutter action.

Practicality

To me it’s an interesting camera but I’m not sure if it really has a comfortable home these days. It does not offer the level of control of a manual rangefinder or SLR, and it does not offer the automation of an auto-focus compact with flash, exemplified Olympus’s own Mju. However, they look cool and are sold for reasonable money. As I write this, you can pay a couple of hundred dollars and get a tested or refurbished one, even with snazzy custom leatherette. Back in the day, anyone who wanted to bring back holiday snaps needed a film camera. Today, shooting film means that you want to, not that you have to. If there’s a problem with the Trip 35 I’d put it like this: it’s not quite easy enough for those who want to shoot film but don’t want to know anything at all about cameras, and yet it does not quite offer enough control for those who want to do it all themselves.

Specs and features

What’s the heart of a Trip 35? The auto exposure and a great lens in a nice compact and light metal body.

The lens is a 40mm f 2.8 and it’s sharp. That just about covers it. But how sharp is sharp? Sharp in this case means if you shoot the 400 ISO colour negative film that (I reckon) you should be shooting the lens will out-resolve the film. If your shot is soft it’s because you missed focus or something moved. If you know you’ll be shooting in good light then by all means pop in some Ektar 100 and go for your life – you won’t be disappointed. If you’re feeling brave put in some Ektachrome. If you’re thinking, “AHA – but a 40mm 2.8 at minimum focus of three feet will give me a DOF of… etc. etc.” then go your hardest but I’d say the Trip 35 is not a camera that makes that kind of promise.

BUT let’s see how this plays with the aperture and exposure.

The auto exposure works like this: the meter selects one of two shutter speeds, 1/40th or 1/200th of a second. Other adjustment comes as the camera changes the aperture from f 2.8 to f 22

If there is too little light for 1/40th and f 2.8 a little red flag pops up on the viewfinder and the camera will not fire (unless you make it fire – more on that later.) ASA is set manually around the lens barrel, so if you want to shoot your Portra 400 at 320 it’s entirely up to you. (ISO tops out at 400 though.)

This really is what makes this camera what it is; there’s the ability to bend the rules somewhat regarding how you make it behave, but it will keep you out of trouble unless you persuade it not to. (In part two of this series I take it to Italy and go all arty with it.)

I bought my Trip 35 at a time when I had not yet returned to shooting film. I saw it looking neat and clean in a camera shop, was aware of its provenance and how it functioned, but had no real use for it. It was $50 so I bought it. In the 80s I had used a few different types of viewfinder cameras, at least one compact viewfinder camera that had auto exposure out to a second or more and an electronic shutter, but I have no idea now what model that was.

In Use.

The first time I used my Trip 35 was a trip (see – a trip!) to Aotearoa/New Zealand in 2019 with my daughter who had been shooting my old FM for a couple of years, having lugged it around the world on her travels. I was dabbling in film again – but only roll film at that time. I had just rediscovered a 6×6 folder in the cupboard and was using that to make in-camera multiple exposure panoramas. I took the Trip 35 just for fun, thinking that the shots on my Fuji XE-2 with the 27mm pancake would be the money shots. This was the trip where I learned that the film shots were much nicer. We were both shooting Portra 400 exclusively in those days (I now shoot Portra 160 in 135 and Portra 400 in 120). I recall that we’d look at the light on a scene and instead of saying “Oh, that looks nice!” we’d say, “Oh, that will scan up nicely!”

The set that I brought back from New Zealand (I shot two rolls of 36 over ten days) highlighted for me a different type of travel photography. Perhaps it’s more accurate to say it’s an older type of photography. It was not trying to be arty or clever, it was just about making nice photos of our trip; the things we did and the places we saw. It was the lakes and the mountains, the places we hiked and camped.

The Trip 35 is still ideal for this type of shot. Let’s have a look at why I think this is:

Manual Zone Focus. To focus a trip you choose one of four distance settings, essentially very close, close, near, or far. Most of the time it’s far. If you want to get fancy theres a distance scale on the bottom of the lens barrel. This is often better, quicker and more reliable than an AF camera where you can hear it hunting, or where Infra Red AF might get tricked by heavy fog. The only downside is that you might leave it on the wrong setting. There is a reminder in the viewfinder window, but that is very easy to overlook. I only lost one shot because of the oversight, but, yes, it is possible to forget and loose a whole bunch if you screw it up.

Manual Winding. The camera is ready as soon as you take the lens cap off and it just makes a nice click as you shoot, not a clunk and buzz as it winds on.

No Flash: The Trip 35 is a great outdoors camera, and not such a good indoors camera.

Here’s where it’s a good time to talk about how clever the camera is:

Lots of point and shoots that have built in flash are too eager to fire it, and they’re not clever enough to know that their built-in flash will not illuminate a mountain on the horizon. This does not happen so much these days now that people use their phones, but if you think back to concerts or sports matches years ago there would always be flashes going off in the audience when people were trying to take photos of the action. The camera would sense it was dark and fire its flash, without working out that the flash was absolutely no use in that situation. You would have to disable the flash manually which was often a pain in the arse.

The trip 35 senses if there is enough light for a shot, and if not it will throw up a little red flag in the viewfinder and the stutter will not fire. This also prevents you from taking a shot if you’ve left the lens cap on. Bonus. If that’s all you want to know, fine, don’t take the shot. If you’re a more advanced shooter and want more control, you can have that too. If you flip the aperture ring away from A and set an aperture, the camera will shoot anyway at the aperture you set and 1/40th of a second. This is great when you’re using your manual flash, but also useful if you want to make a low-light shot. Let’s say it’s dawn or dusk and the light is nice but it’s a bit dark for a correct exposure. Just flip the ring to 2.8 and you’ll have a frame made at 1/40th and f 2.8. Bingo. Flip it back to A afterwards and you’re back to auto again.

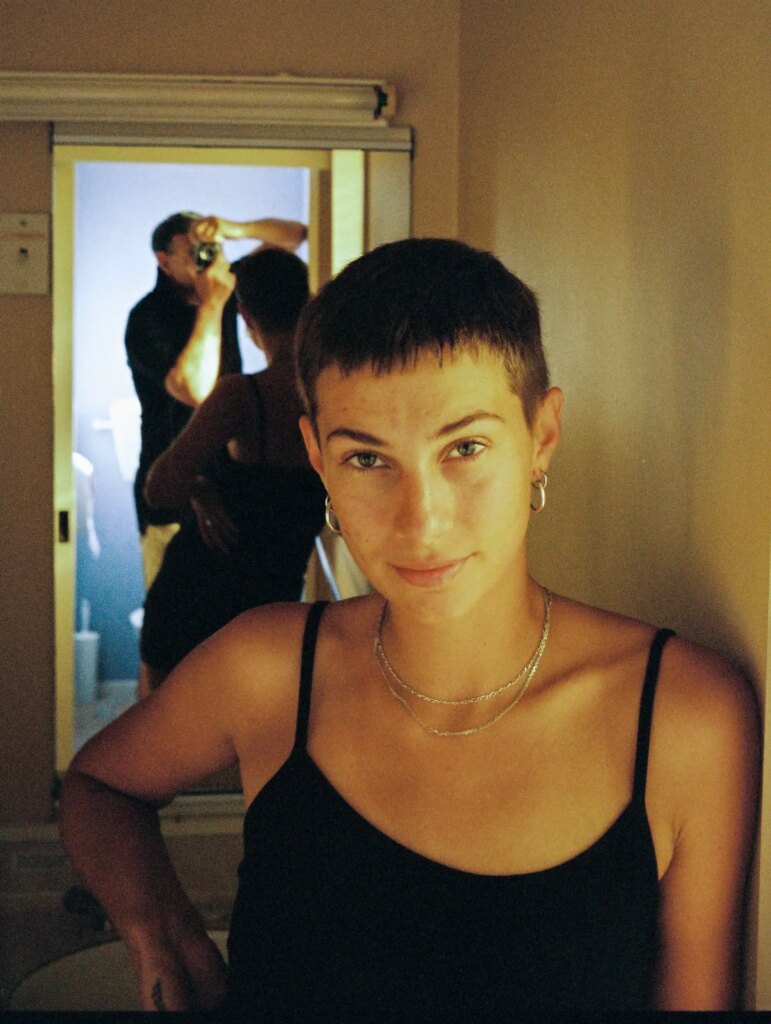

Heading home there was a shot left on the roll so I zone-focussed for this dual portrait mirror-selfie as we were leaving the hotel. The Trip 35 is not the camera you’d pick for this type of shot, but it shows that it can be done and the lens performs nicely if you nail focus. The best camera is the one you have with you and all that.

In part two of the “Trip 35 on Holiday” series I take the camera to Italy and go all arty with in-camera panos in the Dolomites, multiple exposure window selfies in Venice, and more… Stay Tuned!

You can also find Hamish’s old review of his Trip 35 here

Share this post:

Comments

Markus Larjomaa on Olympus Trip 35 on Holiday – Part 1 – Keeping it Simple in New Zealand – by David Hume

Comment posted: 28/10/2022

Comment posted: 28/10/2022

Comment posted: 28/10/2022

Comment posted: 28/10/2022

David Hume on Olympus Trip 35 on Holiday – Part 1 – Keeping it Simple in New Zealand – by David Hume

Comment posted: 28/10/2022

Bob Janes on Olympus Trip 35 on Holiday – Part 1 – Keeping it Simple in New Zealand – by David Hume

Comment posted: 28/10/2022

The Trip does slip into a jacket pocket very easily. Using it recently has reminded me a lot of the later XA2.

Comment posted: 28/10/2022

Huss on Olympus Trip 35 on Holiday – Part 1 – Keeping it Simple in New Zealand – by David Hume

Comment posted: 28/10/2022

I bought one recently because it was a really good deal on one that had been serviced by Tripman. So it was in perfect shape, with nice green leather. Shot two rolls, pics were nice, sold it on for a little profit. The reason being is it reminded me that I do not particularly like cameras with thumb wheel advances - there is nothing satisfying in that and it is not comfortable. And I already had a bunch of smaller and better zone focus cameras - like the incredible Ricoh FF1 and FF1-S. Much smaller than the Trip, much sharper lens, much greater auto exposure range, and a single stroke film lever advance!

The Trip is that in between size - too big to be pocketable, but sort of too small to need a neck strap! I enjoyed the experience so that I could check that off the classic cameras that I wanted to try out.

Comment posted: 28/10/2022

Comment posted: 28/10/2022

Comment posted: 28/10/2022

Shawn Granton on Olympus Trip 35 on Holiday – Part 1 – Keeping it Simple in New Zealand – by David Hume

Comment posted: 28/10/2022

Oh yeah, I echo what Markus said above: If you switch the aperture ring from A to 2.8 and point it at the sun, as long as the selenium cell is working it'll take the shot at f/22.

One tip for focus: I usually leave the focus ring at the "group" setting (two people) as that is often the best focus distance. Olympus themselves thought so, marking the pictograph for that focal distance in red vs. orange for the others. (They did the same thing with the XA2, where not only the group focus is demarcated in orange, but also that the camera resets to this focus distance when the clamshell is closed.)

Comment posted: 28/10/2022

Comment posted: 28/10/2022

Comment posted: 28/10/2022

Comment posted: 28/10/2022

Vazma on Olympus Trip 35 on Holiday – Part 1 – Keeping it Simple in New Zealand – by David Hume

Comment posted: 29/10/2022

Comment posted: 29/10/2022

Comment posted: 29/10/2022

Nick Orloff on Olympus Trip 35 on Holiday – Part 1 – Keeping it Simple in New Zealand – by David Hume

Comment posted: 29/10/2022

It doesn't get a lot of use - too many other cameras to play with - but it's certainly fun to use.

99% of the time I'm happy with the results, and the only issue I seem to have is it doesn't cope well with sun flares.

Comment posted: 29/10/2022

Comment posted: 29/10/2022

Dan Smouse on Olympus Trip 35 on Holiday – Part 1 – Keeping it Simple in New Zealand – by David Hume

Comment posted: 31/10/2022

Comment posted: 31/10/2022