Out of all the gear and films I’ve written about over the last few years, none has provided me with a more daunting task to review than this lens, the Leica 90mm f/2 APO. There is so much for me to balance in order to offer an accurate, measured, and importantly unbiased assessment of my absolute favourite lens, representing what I feel is the best focal length for my photography, and the absolute pinnacle of optics with which to comprise that length. My story with this lens is not one of love at first sight – as with my current frustration with 35mm I found it a chore to adapt the way I had learned to that point to see at 50mm on the rangefinder, and to work out exactly it would give me depending on where I was standing.

The f/2 APO lens was the second 90mm I owned for Leica, bought only a few weekss after I tried a Tele-Elmarit Thin option. This had been nice, but something about it felt like a half measure, and I decided if I was going to make this focal length work for me then I was going to have to go for the extreme.

I try my best to keep my gear streamlined, and once I am comfortable with what a lens offers me I will chop and change until I have the best balance of quality and budget. For my 50mm options this means a Zeiss Planar and for 35mm a 7artisans – but this 90mm has survived them all, staying with me all the way through from some of my first ever assignments on the M240 all the way through to my work today on the M10, and personal projects on the M6. It has travelled to many countries, and captured what I feel is some of my most iconic work. This is currently what my eye searches for when I assess ways to frame a scene.

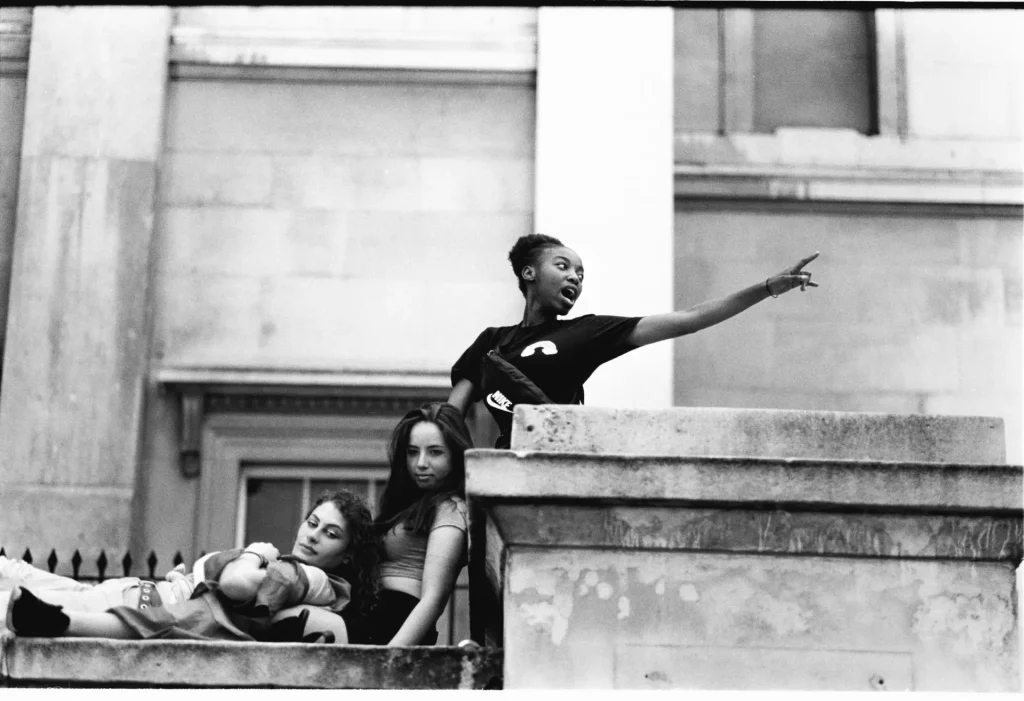

I shot this lens first at London Fashion Week, which is the environment I cut my teeth in most rangefinder methodologies. It is crowded, fast paced, and never wanting for interesting characters, which makes it the perfect place to practice wide open rangefinder focusing.

At the time I associated the length with classic portraiture, and didn’t think much about using it for street photography, but I found myself experimenting more and more with what the lens offered. This actually took a bit of forcing, as I was more inclined to find things to shoot with a 50mm mindset, so I ended up leaving my 50 at home and shooting only at 90 – which left me with lots of “nothing” days, but over time I became more and more used to it, until now where I can find it difficult to think in terms of anything else!

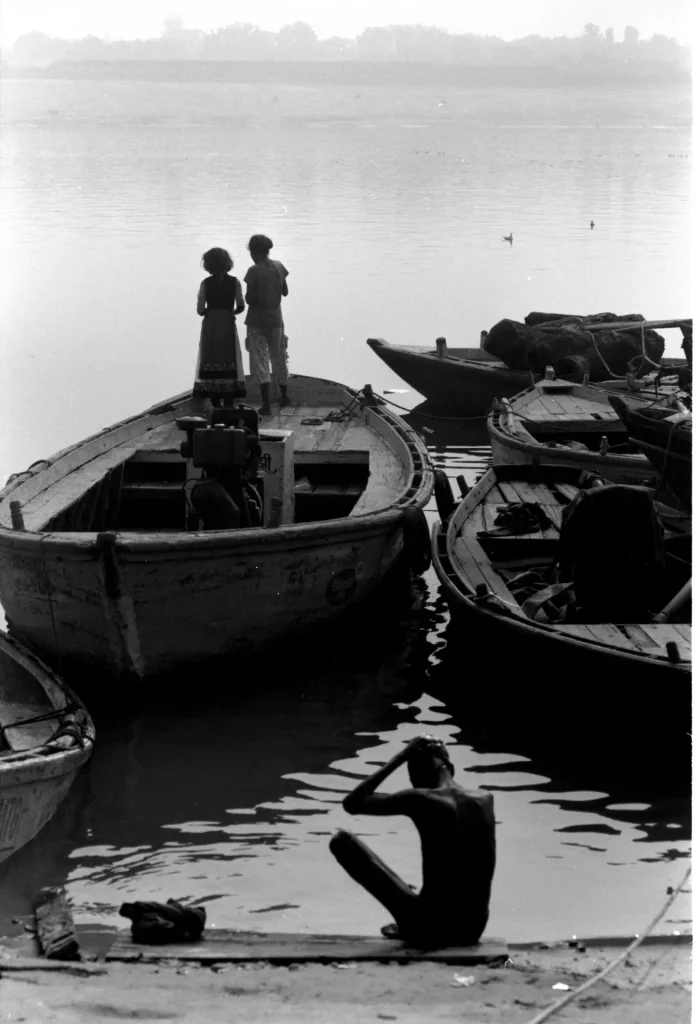

In 2016 and 17 before I made the big change over to a film workflow I was shooting in more of a new wave street style, which meant emphasising composition, light, and atmosphere, over the evenly exposed, interesting scenes I try to find today. The smaller field of view of the 90 means a very elegant crop around any selection of shapes you may want to include, and makes this kind of geometric detail based shot easy at far to mid distances.

Now that I shoot mostly on film I find I am going for a much closer view of more energetic situations, and this lens does not slow me down in that area at all. It takes practice to focus fast at any length on a rangefinder, but once you can nail it you don’t need to worry about much.

For any kind of events journalism this lens is a fantastic all rounder, and one I’ll always be sure to keep with me – but for the majority of photojournalism these days I find myself drawn to 50mm. I think it’s just a touch more versatile for situations I know I’ll be able to move through a crowd, or be comfortable up closer – I know I can always move a certain way with a 50, whereas with a 90 I’ll find myself needing to step back. 90 is more an intuitive shooting option, whereas if I’m actively moving and searching then a 50mm serves me a bit better. This is all personal to my method of working, and I’m sure others will be different – it’s not an absolute at all, more something I consider case by case when looking at a situation, and once I know which lens I want to use to tackle things I more or less just stick with that.

The build of the Leica 90mm f/2 APO is as tank-like as any other modern Leica offering. Glass and metal, dense but well balanced. I never have any issues with the weight – it’s heavier than many other rangefinder lenses, but compared to the equivalent spec on an SLR (only around 100g heavier than the legendary Nikon 105mm f/2.5, and the Fujifilm 56m f/1.2) it is very light indeed, which is true of many supposedly “heavy” rangefinder lenses.

I think that the weight can seem one of the only drawbacks to this lens, and it undermines its use for travel situations, or for someone looking for the lightest carry possible. Any of the Tele-Elmarit series or even the f/4 compact 90s will be the lightest options, but really I think a couple of hundred grams is a small price to pay in return for the absolute sublime results that will be consistently delivered.

There are only three moving parts; the focus, the aperture, and the built in lens hood. When I bought the lens the focus was quite stiff, but after years of use it is now wonderfully smooth, and only turns when I want it to. The aperture and lens hood on the other hand have a tendency to wander away from where I need them to be, but I’ve gotten in the habit of checking that things are where I left them, and haven’t yet messed up a shot terribly as a result. I am sure I could get these tightened somehow, but I’m really not that bothered by it.

The focus is augmented with a Taab, which I use on nearly all of my lenses which don’t have a built in option. I find it so much easier to keep one of these in place and allow muscle memory to know where everything is – with a plain circle the focus could be anywhere in the range, but with one of these I know which direction I need to be rotating it before even lifting it to my eye!

I am used to the 0.72x finder on my M6, M2, and M10, and the 90mm frame-lines on these are very easy to see and use. I’ve said this repeatedly but one of my major issues with anything wider than a 50mm is that, as a glasses wearer, it becomes close to impossible to get an accurate idea of what my frame encompasses. By comparison 90mm are some of the easiest to use lines there are, and I find at the longer length that issues like parallax become non-existent. My 90mm compositions are as close to perfect in terms of accurately representing what I saw and wanted to include in that frame.

I’m not often one to talk about lens designs, as they don’t really play much of a role in what I need to be thinking about while shooting, but I always found the theory behind APO designated lenses fascinating. APO stands for apochromatic, which means that it has been designed to reduce chromatic and spherical aberrations almost entirely. It achieves this by accounting for the way that different colours of light travel at different speeds through different materials; the reason chromatic aberration is often purple is because those are the colours that “arrive” slower, and are more dispersed by refraction in a non-APO lens. There are a few Leica lenses with an APO design, and these absolutely deserve their reputation for being the best of the best. There is no special effect, no “look” to these lenses, they simply render the image as precisely as allowed by physics. There are two modern 90mm Summicron lenses, and my choice for the APO version wasn’t really informed by all of this at the time.

Honestly, I think the difference between the APO/non-APO 90mm is marginal, and really not noticeable in everyday shooting conditions. If your use case is for large prints, studio use, or if you tend to shoot lots of back-lit scenes then consider the APO. For the majority of people however the “basic” version is absolutely fine – and for black and white/film only shooters there ought to be no noticeable difference whatsoever.

One of the first times I used this lens in a studio situation was for the Toni & Guy Academy, and back when I was still working with a Sony A7Rii. I had my M240 with a 50mm to capture the BTS stuff, but the studio portraits I covered with the Sony and 90mm. I wasn’t sure how large they’d be printing for the campaign, so made sure to compose as carefully as possible in order to preserve those megapixels for the edit.

These two images below are all from that shoot – I encourage you to load the full file and pixel peep to your hearts content – the resolving power of this lens is really something to see. Critical focus is on the nearest eye to the camera/both eyes if on the same plane.

The results, from a technical standpoint, are simply outstanding. The lens resolved perfectly onto the sensor without any issues, and the sharpness is absolutely sublime. The falloff is fascinating, as these portraits were shot between f/4 and f/8, but at the minimum focusing distance of 1m the depth of field is still razor thin. The eye I focused on is dead sharp, but beyond that I didn’t get the clarity I was maybe expecting from such a small aperture. I remember at the time worrying that this might be a drawback, but the client was happy with the images and I made a mental note to keep that in mind for the future.

For studio style portrait work this is the classic length, but that sharpness can bring out details even the most skilled HMUA has covered up – a mist filter, or netting over the front element can go a long way to adding a bit of glow, and taking that edge off. My preference is a 50mm for most portraits, but as evidenced above this lens for headshot style images is absolutely more than anyone really needs!

Wide open the focus must be incredibly precise, but with rangefinder focusing as long as the kit is well calibrated that’s never been a problem for me. I don’t see any real variation in the way the lens looks throughout the aperture range, from wide open to entirely closed; vignetting, sharpness, and other aspects you may expect to change with that variable remain consistently excellent. No diffraction, no glare, no ghosting. The only artefacts I find on images made with this lens are a result of issues with the film, never the optics to date.

On sharp, T-grain styled films this lens renders like an absolute dream. Ektachrome, Delta, and T-Max combined with this lens will give you some of the highest clarity results available on a 35mm format. If your goal is to print big then any of these emulsions will serve you perfectly.

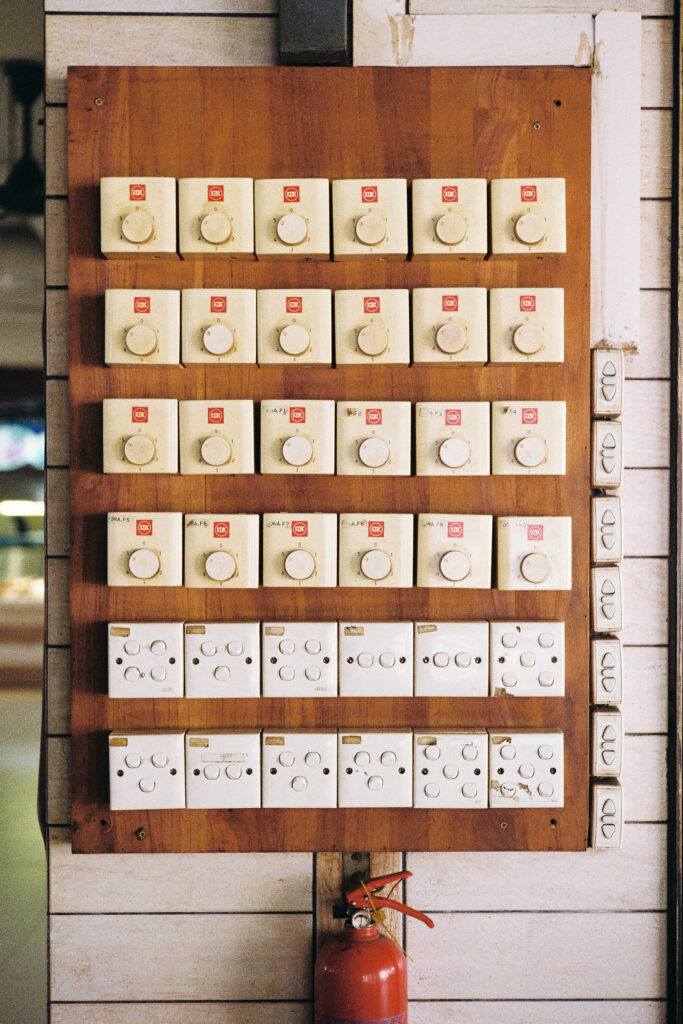

Aside from the more obvious applications so far discussed I’ve found this lens to be incredibly versatile for situations I wouldn’t have ordinarily considered it for. As a still life lens I actually really enjoy the detail it can pull from a scene, either isolating close up, or flattening out at a distance.

All of this comes, of course, with the same caveat any piece on rangefinder lenses ought to have: practice. I mentioned that I spent time with this lens at London Fashion Week, and really that environment is an incredible crash course in honing your ability to react to your surroundings. Any photographers experience of this lens will depend entirely on how much they are willing to dedicate time and effort to learning to feel out the edges of the frame, focus quickly on things moving towards and away from you, and figuring out how best to apply it to your usual style. This lens is a very simple piece of kit, and it’s easy to simply form habits around it, rather than bending it to your will, and understanding exactly what it is going to see. It will do nothing for you, so you will get as much out of it as you put in through practice.

I’m glad I spent that time forcing myself to use this lens to begin with, as it’s really paid off and affected the direction of my work in so many ways. I’m hoping that this same process will affect the use of 35mm in my workflow, although I don’t know that anything will come close to the amount of sheer fun I have with my M6 paired with this lens and some Delta 400 on a bright but overcast day.

Thanks for taking the time to read this article! If you like the images here please consider checking out my Instagram. I buy all of my film from Analogue Wonderland.

Share this post:

Comments

Wim van Heugten on Leica 90mm f/2 APO Long Term Review – by Simon King

Comment posted: 29/05/2020

Thank you for this nice reading and pictures! There is one point where you are wrong. Yous state: "It achieves this by accounting for the way that different colours of light travel at different speeds; the reason chromatic aberration is often purple is because those are the colours that “arrive” last, compared with red which travels faster.". There is only one valie for the speed of light: 299 792 458 m/s (Wikipedia). Chromatic aberation is caused by the varying diffraction of light by glass, depending on the color of the light. It's just physics...

Comment posted: 29/05/2020

Jonathan Leavitt on Leica 90mm f/2 APO Long Term Review – by Simon King

Comment posted: 29/05/2020

Comment posted: 29/05/2020

Comment posted: 29/05/2020

Comment posted: 29/05/2020

Comment posted: 29/05/2020

Comment posted: 29/05/2020

Terry B on Leica 90mm f/2 APO Long Term Review – by Simon King

Comment posted: 29/05/2020

For a long time my personal arsenal comprised of 50mm and wider lenses, with little recourse to anything longer. Having played with 135's on RF cameras I soon got the message that a 135 wasn't really needed for my interests, but I latched on to the 90mm when a work colleagued introduced me to Leica slr in the early 1980's and the weight of the f2.8/135 Elmarit wedded to the R3 was simply too much. So I ended up with the f2.8/90 Elmarit instead. Even then, though, the combined weight of the R3 28 50 90 outfit was a bit much. Anyway, I digress.

I very much warmed to the FoV of the 90, especially for recording street scenes (not the type of street photography very much in vogue today) where a tighter viewing angle and judicious use of perspective would yield the subject in a different light, so to speak. Often, when I had time, I would I would walk around a small village, say, shooting with just the 50 and/or 28, and then follow the same route shooting with just the 90mm. I was surprised by how I viewed the subject with a different eye, far more so than if I changed lenses during the walk around.

I still favour the wider angle lenses, but with the Leica C version of the f4/90 Elmar, I know I've got a fine lens. The Apo versions are the ones to use, providing the ultimate in IQ, but as you say, for the majority of users/usage, we're unlikely to tell the difference.

If I may, I'd like to question your interpretation of how an Apo lens works, especially where you point to the speed of the different wavelengths of light being responsible for them arriving at different times. Going on my understanding, all wavelengths travel at the same speed, but it is only whilst passing through a substance that they forced to slow down. In its simplest form, the trajectory of a light wave passing through, say, a single glass lens element gets bent and it does indeed slow down whilst passing through the lens, but when it exits it reverts to its original speed as before it entered the lens, but on a different path.

The three colours which a lens needs to correct would, if not corrected, focus at different points at the film plane. This is due to their different wavelengths, but is caused by their passing through glass which bends the rays to different degrees depending upon their wavelength, not in a difference of speed of their arrival. Thus the job of the lens designer is to make the scattered rays exiting a lens converge to a point of focus at the film plane. The majority of lenses make an excellent job with correcting just two wavelengths, but the apo designs are to correct for three wavelengths.

Comment posted: 29/05/2020

Jamie Winder on Leica 90mm f/2 APO Long Term Review – by Simon King

Comment posted: 30/05/2020

Comment posted: 30/05/2020

Robert C on Leica 90mm f/2 APO Long Term Review – by Simon King

Comment posted: 04/06/2020

Layer Elements with Longer Lenses in Street Photography - ArYa World Online on Leica 90mm f/2 APO Long Term Review – by Simon King

Comment posted: 03/05/2021