Photography and Jazz music are two sources of inspiration in my life. They are my muses. In Jazz music, there is an emphasis on improvisation. Musicians often create impromptu solos and melodies during performances, building on the musical core. Similarly, film photographers often work with finite control over the final image. As many of us, analog photographers are aware, the development process and the nature of film can lead to beautiful, unpredictable, and one-of-a-kind results. This element of improvisation in both allows for artists to produce creations full of spontaneity and individual expression.

“I didn’t write the rules. Why would I follow them?”

– W. Eugene Smith

Five photographers chronicled Jazz culture and its artists when Jazz was arguably at its height of cool. These photographers documented the essence and spirit of the music, showcasing the marriage of the two art forms in their own unique style. This is by no means a complete list of Jazz Photographers. However, through their lenses, we have a unique perspective of when Jazz was king in America.

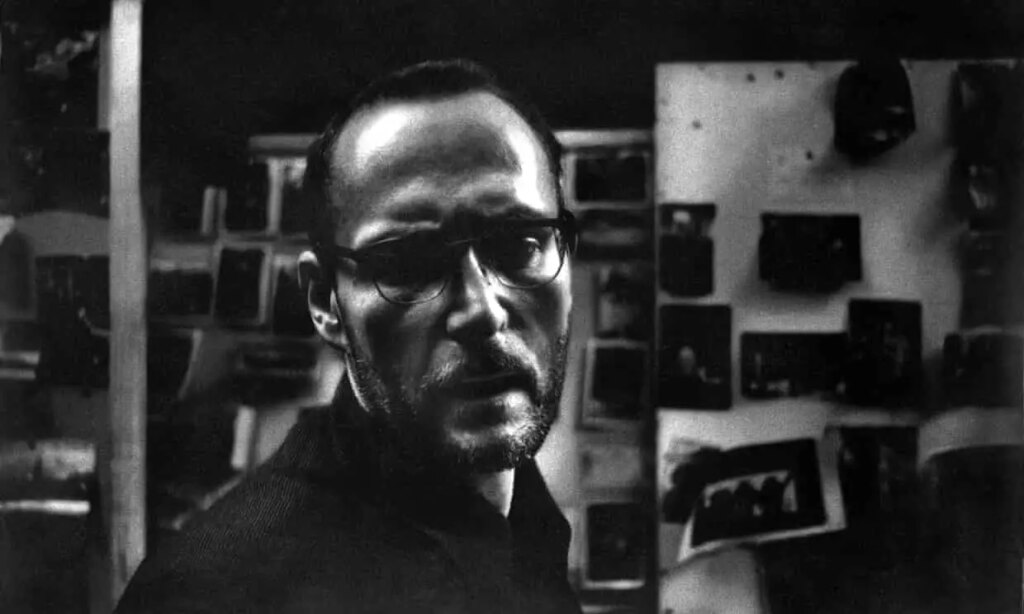

W. Eugene Smith

December 30, 1918, Wichita, Kansas – October 15, 1978, Tucson, Arizona

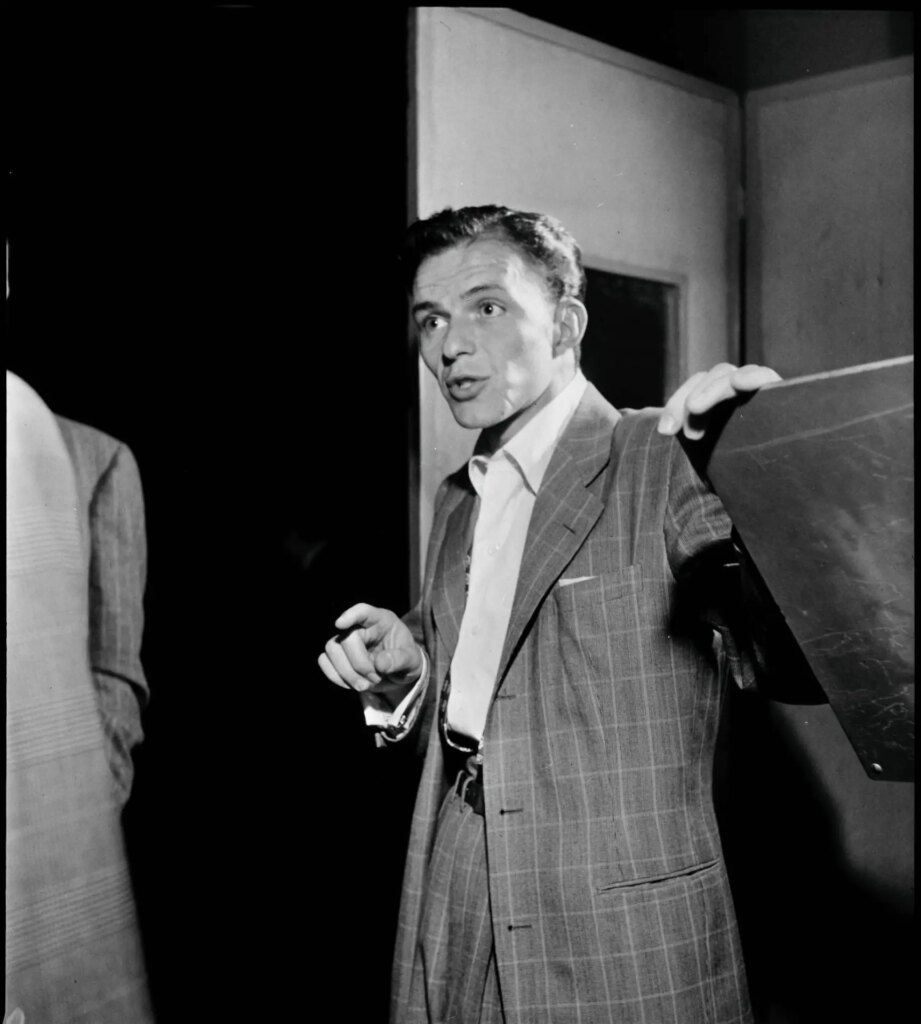

W. Eugene Smith is one of my favorite photographers. Few photographers matched his obsession with producing images to tell a story. His photo essays in LIFE magazine would make him famous. Despite the acclaim and admiration he received in photographic circles, he was never satisfied. He desired more. He desired to be free from the confines of his suburban domestic life and the editorial restrictions placed upon his work at LIFE magazine.

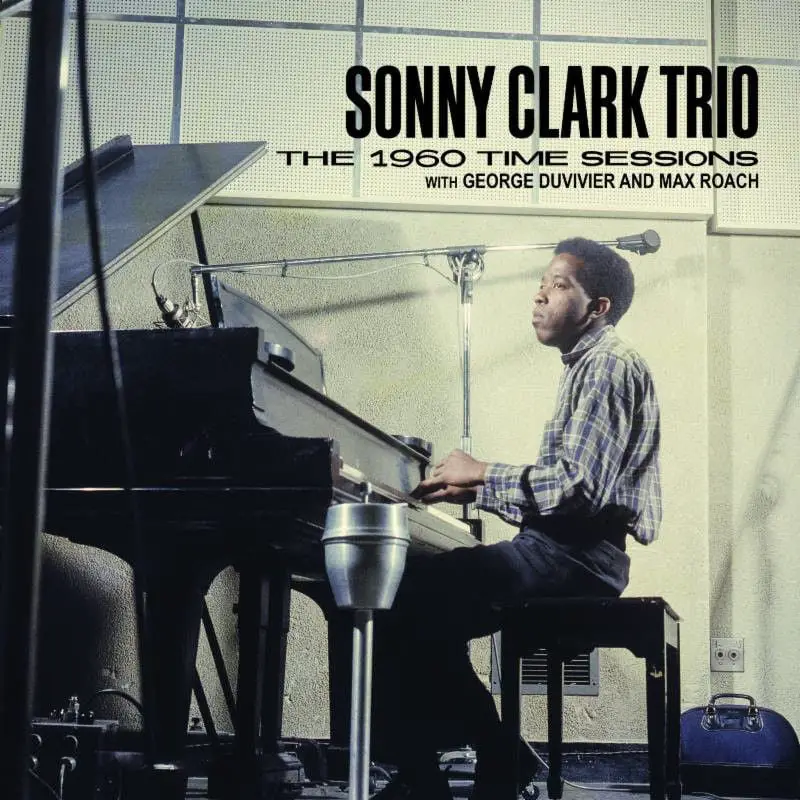

His desires led him to a seedy 4th-floor loft at 821 Sixth Avenue, near West 28th Street in NYC. From 1957 to 1965 Smith became fixated with the bohemian lives of the New York City artists in the building and with the lives of the people in the surrounding neighborhood. Smith would take over 40,000 pictures and make over 4000 hours of audio recordings of daily life in and around the Sixth Avenue loft (later known as the Jazz Loft) One recording captured the near death of Jazz pianist Sonny Clark from a heroin overdose.

The building was a hangout for Jazz musicians to chill, jam, or come off a high. Many of Jazz’s royalty came through its doors Sonny Clark, Stan Getz, Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, Teddy Charles, Bill Evans, Alice Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, and Zoot Simms. However, there was a multitude of unknown others that Smith’s mics and lenses captured.

Smith’s presence at the Jazz Loft was both unobtrusive and magnetic. Because of his prior experience as a photojournalist; he had a way of blending into the background, becoming an invisible observer while still capturing that “decisive moment”. Smith’s images were not just about documenting the musicians but also conveying the pure unadulterated spirit of Jazz and the artists who dedicated so much of their lives to the art form. Smith’s pictures and recordings are a time capsule of New York, Jazz, and a man’s obsessions.

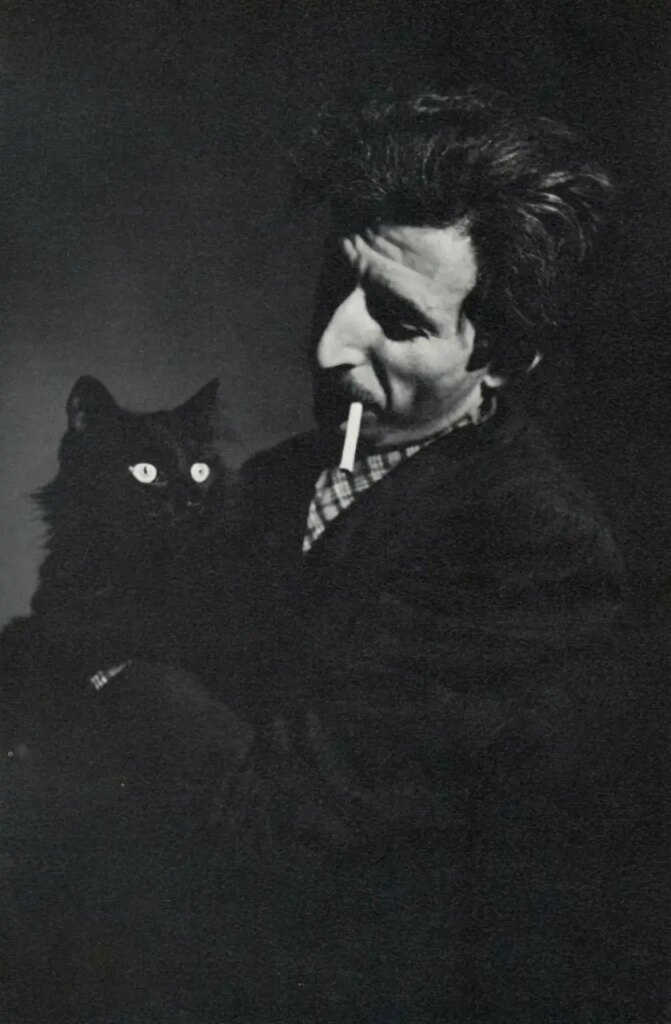

Gjon Mili

November 28, 1904, Korce, Albania – February 14, 1984, Stamford Connecticut

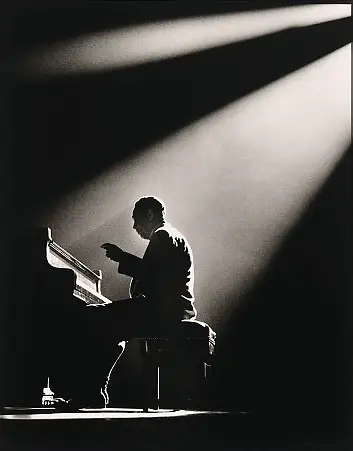

Originally trained as an engineer at MIT and self-taught in photography, Gjon Mili’s fascination with Jazz began after a Louis Armstrong concert in 1939. From that moment he became enamored with Jazz and its performers. Mili was drawn to the improvisational nature of the music, its vibrant spirit, and the profound emotions that it evoked.

He also became famous for his unique approach to capturing motion and light. He experimented with long-exposure photography and pioneered the use of stroboscopic techniques, which allowed him to capture movement with incredible precision.

Along with his personal idol Louis Armstrong, Mili would photograph Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, and countless others. He would have legendary jam sessions going well into the early mornings at his studio where he photographed the epic performances of the Jazz world’s elite.

In 1944, he directed the Oscar-nominated short film Jammin’ the Blues for Warner Brothers featuring Lester Young.

Mili was not just a photographer. His innovative techniques and profound understanding of light and motion allowed him to create visually stunning images that transcend time and continue to influence the way we perceive Jazz music. Through his lens, he captured the energy of an era, immortalizing the legends of Jazz and leaving a lasting mark on the history of both photography and music.

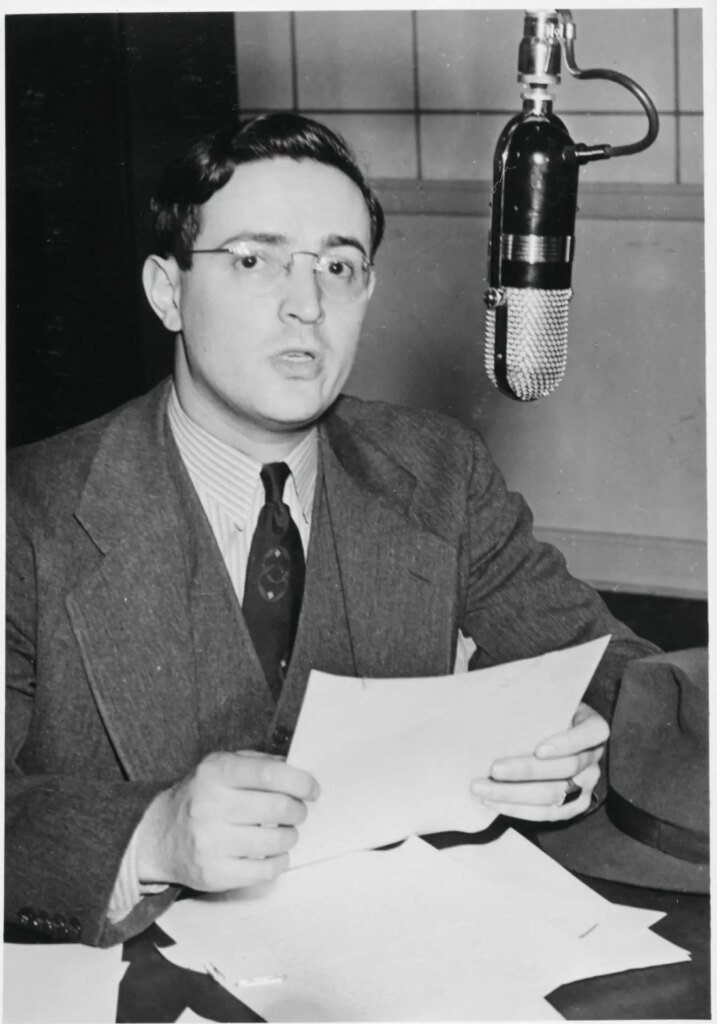

William Gottlieb

January 28, 1917, Brooklyn, NYC – April 23, 2006, Great Neck, New York

Gottlieb was a photographer during the golden age of Jazz from the 1930s to the 1940s. Gottlieb would pick up the camera early in life. He captured the cosmopolitan streets of New York as a teenager. He further perfected his craft as a photographer for his school newspaper at Lehigh University. In New York City, he became mesmerized by the music which would lead him to the epicenter of Jazz, Harlem. There he attended performances at the legendary Savoy Ballroom, Minton’s Playhouse, and The Cotton Club.

Gottlieb’s passion for music and photography would merge, setting the stage for his remarkable journey into the world of Jazz. His frequent journeys into the Harlem Jazz scene, eventually allowed him to establish close friendships with some of the genre’s pioneers, including Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Ella Fitzgerald, Thelonious Monk, and many others. His genuine connection with these musicians allowed him to capture candid and intimate moments that brought out the unique characters of the performers.

Additionally, Gottlieb’s photographs contributed to the documentation of Jazz history. As the Jazz movement evolved and new artists emerged, his photographs remained invaluable references for, historians, musicians, and Jazz enthusiasts.

Herman Leonard

March 6, 1923, Allentown, Pennsylvania – August 14, 2010, Los Angeles, California

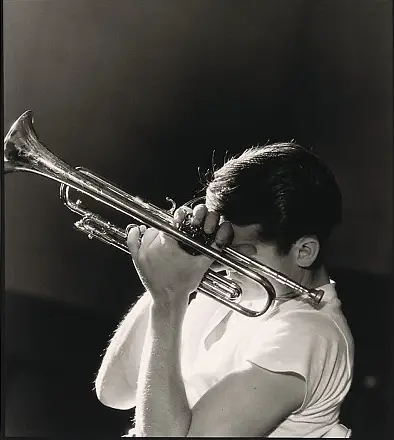

After serving with the United States Army during World War II, Leonard received a BFA degree in photography in 1947 from Ohio University. At university, he would also meet and form a lifelong friendship with fellow Jazz photographer Chuck Stewart.

Like all of the photographers in this article, he found his way to New York. There he opened a photography studio in Greenwich Village. During the day, he would work freelance for various magazines but in the evenings, he would immerse himself in the thriving Jazz scene in clubs like the famous Birdland.

His approach to taking pictures was more than just pointing a camera at musicians; it was a deeply artistic and emotional endeavor. He used available light and took pictures at angles looking up at the artist making them larger than life. He possessed an extraordinary ability to capture the mood and atmosphere of a performance, freezing moments that seemed to reveal the character of the musicians. His photographs were not merely snapshots but rather visual stories that pulled the viewer into the music.

Leonard’s legacy lies not only in the technical excellence of his images but also in his ability to convey the raw emotions, passion, and power of Jazz. His pictures are timeless.

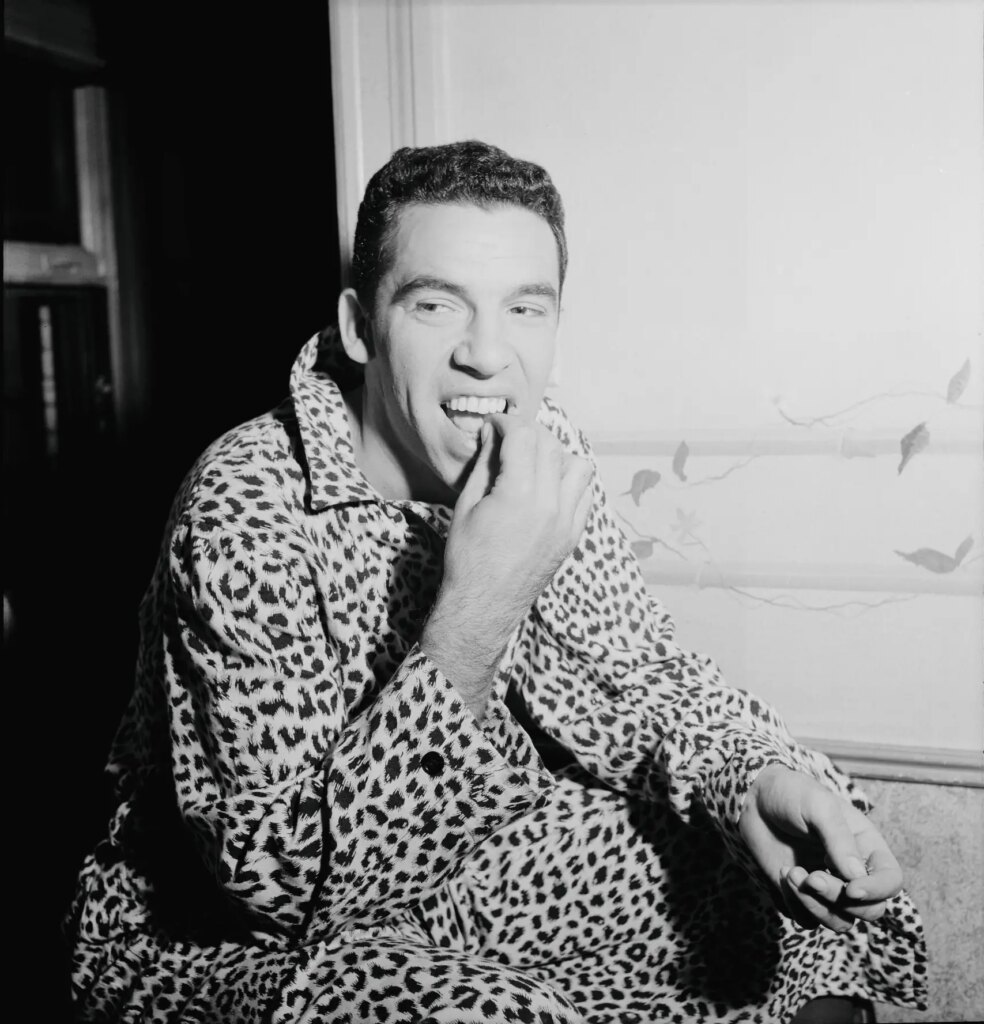

Chuck Stewart

May 21, 1927, Henrietta, Texas – January 20, 2017, Teaneck, New Jersey

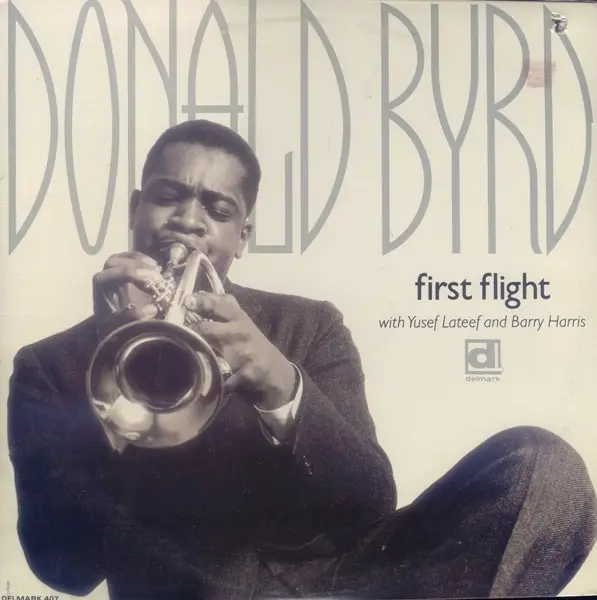

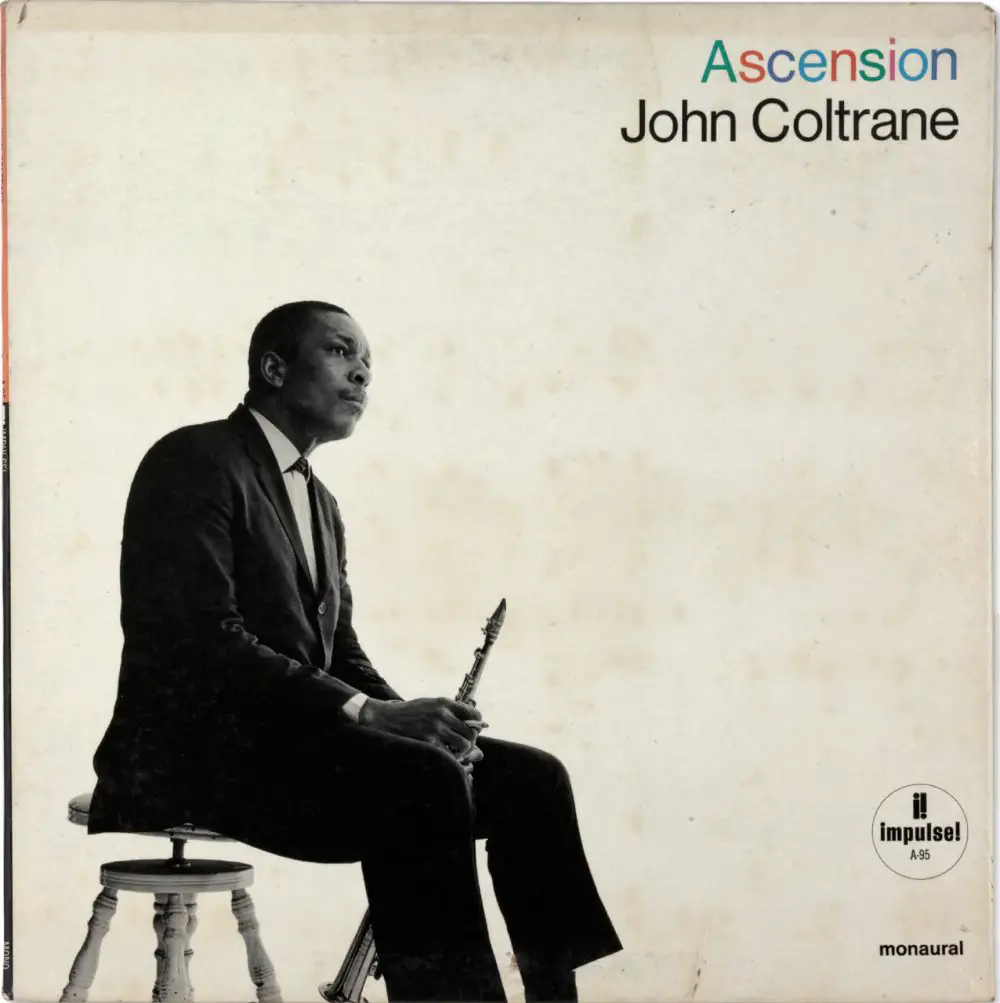

You may not know his name but if you’re a fan of Jazz from the 50s and 60s then you have seen Chuck Stewart’s work. He produced images for more than 2000 album covers over the course of his career, most for Impulse records. He was also the only photographer to document the recording sessions of the groundbreaking Jazz album “A Love Supreme” by John Coltrane.

Chuck Stewart received his BFA in 1949 from Ohio University, one of the few schools that offered a photography degree and allowed African-American students. There he would befriend Herman Leonard. After graduation, Stewart joined his friend in New York City and assisted him with the lighting and set up of some of his iconic images. When Leonard left for Paris to be the personal photographer for Marlin Brando, Stewart took over his studio and came into his own as a photographer.

Stewart was in demand from the top music labels and producers in the 50s and 60s. He was a technically gifted photographer but he was equally talented in forging meaningful connections with his subjects that allowed the viewer to see the humanity and vulnerability of the artist in his images.

Stewart’s photographs were not only significant for their artistic value but also for their historical importance. Sadly, in this period, racial segregation was still a bitter reality in parts of America. Jazz provided a platform for unity and understanding. Stewart’s images captured moments of collaboration between black and white musicians, showcasing the power of music to transcend racial divides.

Conclusion

Film photography and jazz music share an artistic spirit, a blend of technical prowess and creativity, and a deep connection to history and culture. These similarities make them captivating and timeless forms of artistic expression. The 5 photographers highlighted offer us a gift, not just from their outstanding imagery but also underscoring the genius of the artists they photographed.

Share this post: