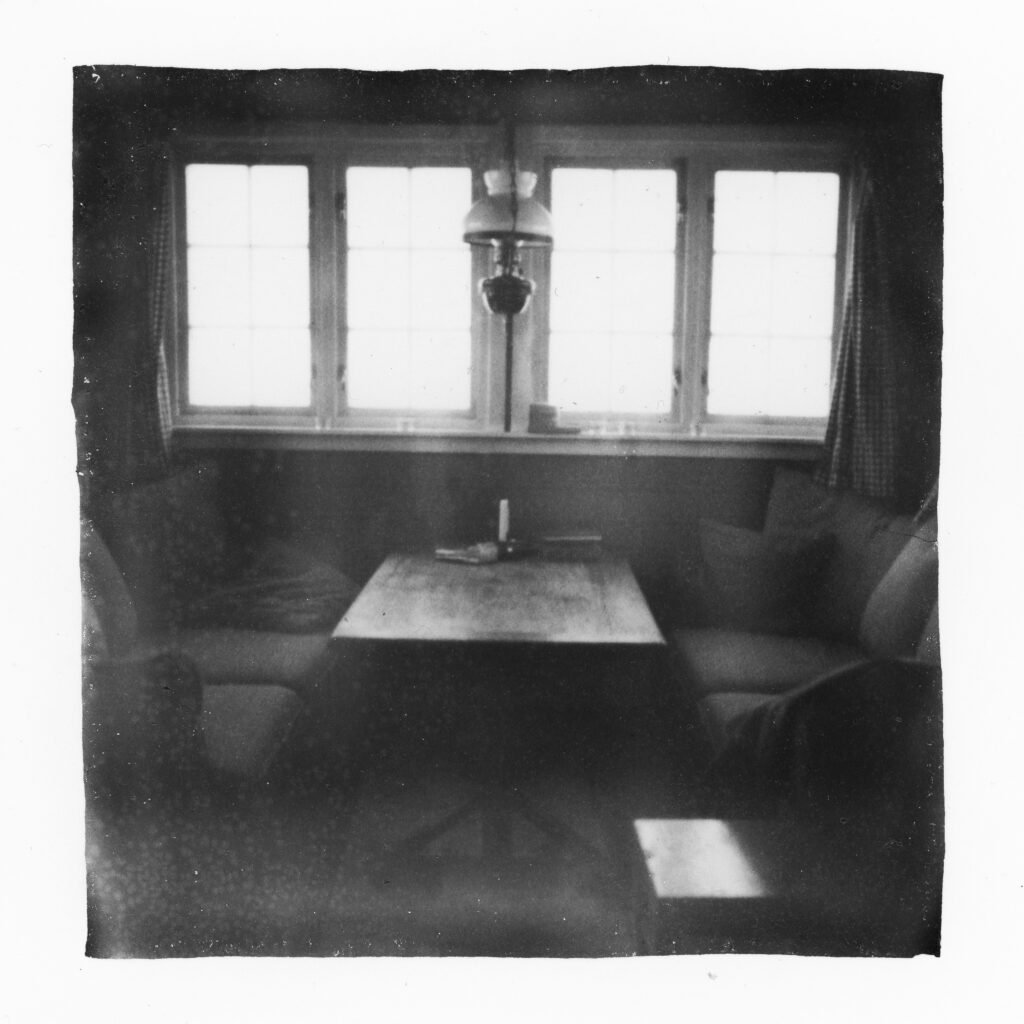

Well, here we are. Once every while during the pursuit of your passion you get to wonder what’s wrong with you to make you end up in the current situation your in. For me, this was sitting in a lonely room at night on a remote arctic research station in the middle of nowhere at times where other people would rightfully sleep, to tinker around with an oven form snatched from the kitchen, an equally “borrowed” kettle, a brush and paper and some polaroid shots of questionable quality towards some results that could best be described as “experimental” – but let’s get not ahead of ourselves.

To set the scene for what’s to come below I first need to make a confession: I recently fell into the dark and financially terrifying Polaroid rabbit-hole. Unexpectedly, I might add. Until a couple of months ago I never paid much attention to the format. To me, the bulky and rather ugly plastic box cameras commonly used seemed to produce only technically mediocre yet expensive fridge or teenager pin wall decoration. This all changed when I picked up a copy of the book “Instant light: the Polaroid’s of Andrej Tarkovsky. There’s something to his pictures that made me want to try the format for myself. In terms of hardware I chose to go with a SX-70 that to me with its folding mechanism and SLR-viewfinder represents one of the technical milestones of the analog era.

After taking a few test shots of the newly acquired camera, I soon came to realize that a correct exposure is much harder than with “a normal” film camera. In addition, the SX-70 only offers a +/- 1.5 Stops exposure compensation dial with which in some situations it really boils down to trial and error. While the pictures are nice to hand away to friends or family, at some point I started to get more interested in experimental techniques and manipulation of the pictures.

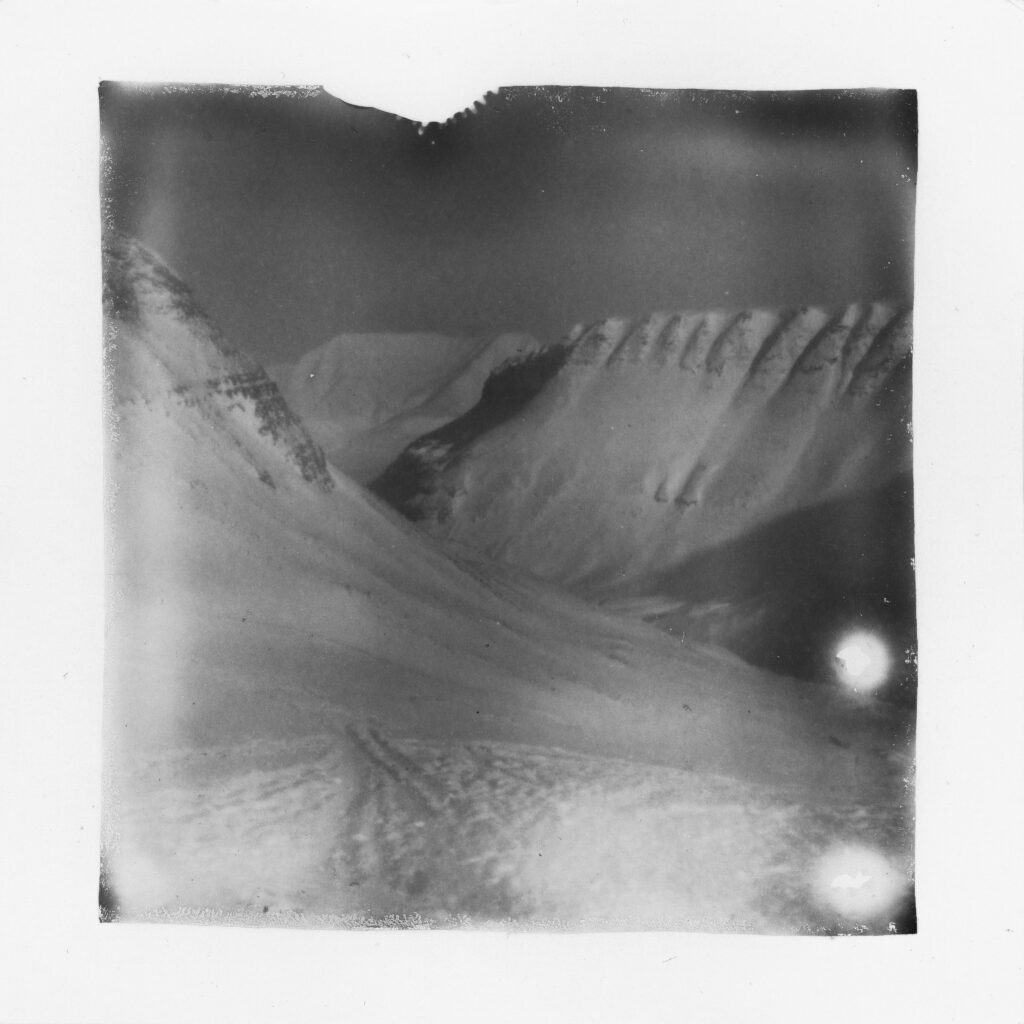

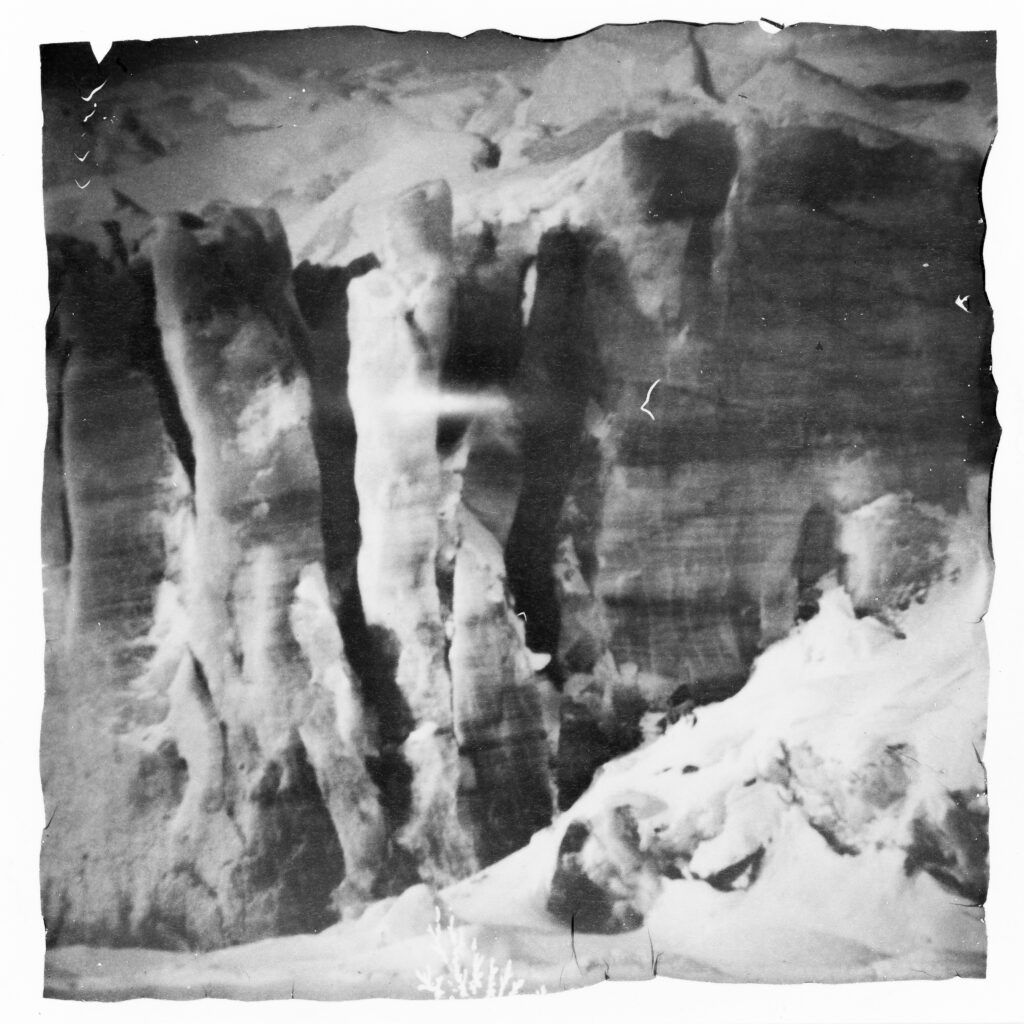

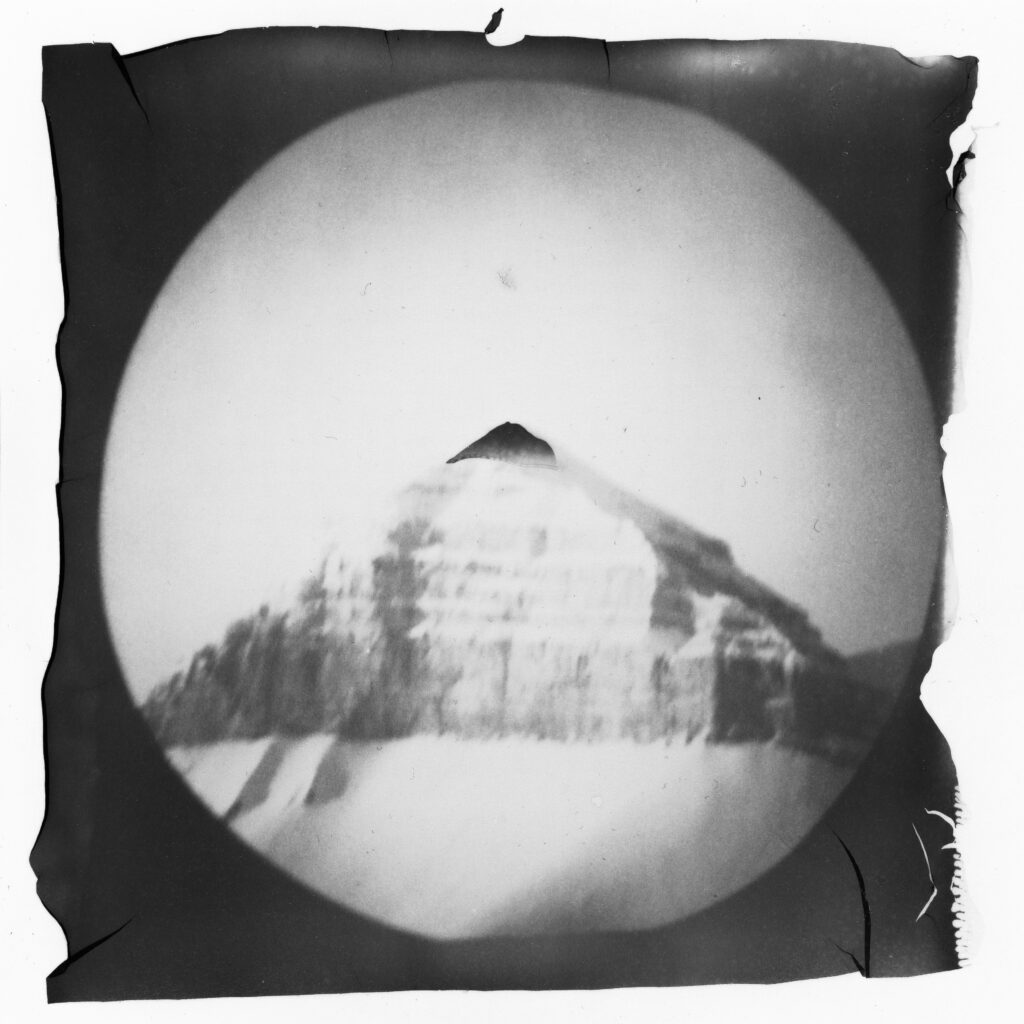

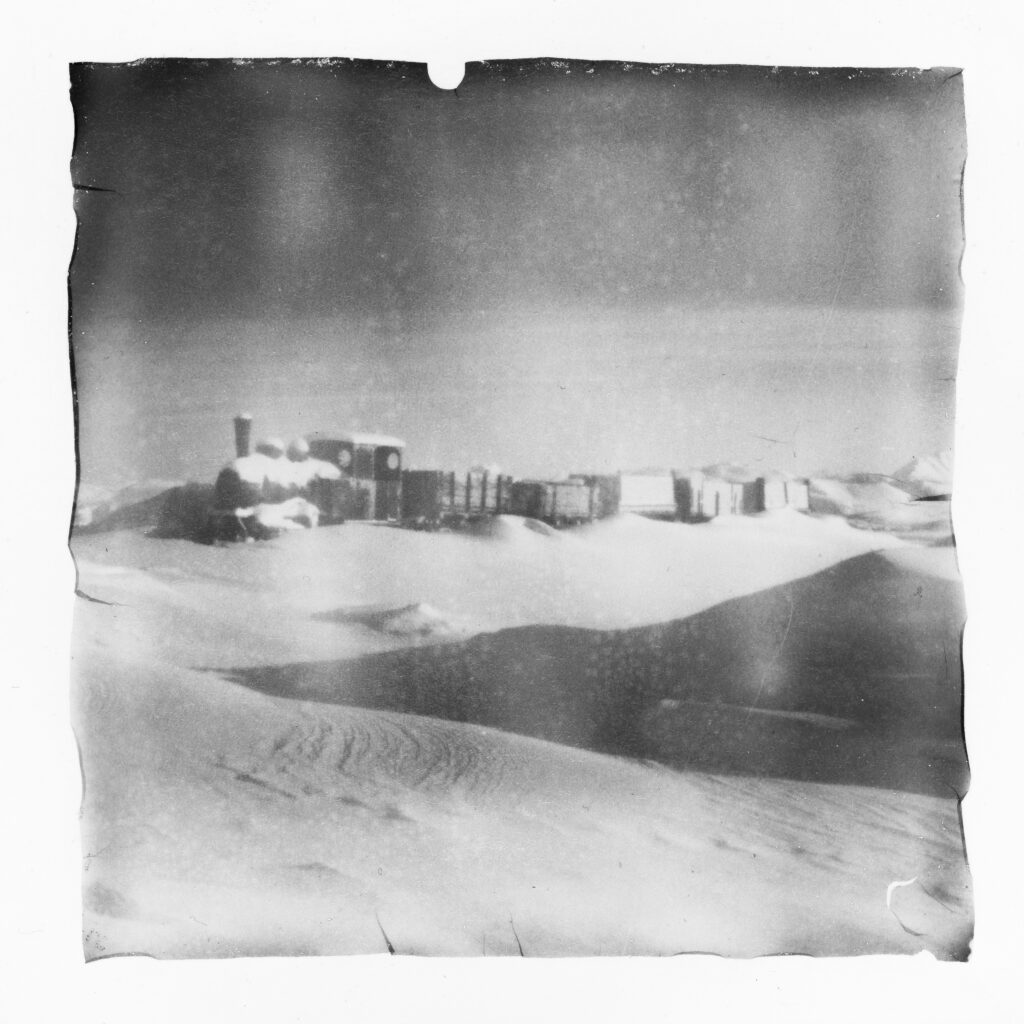

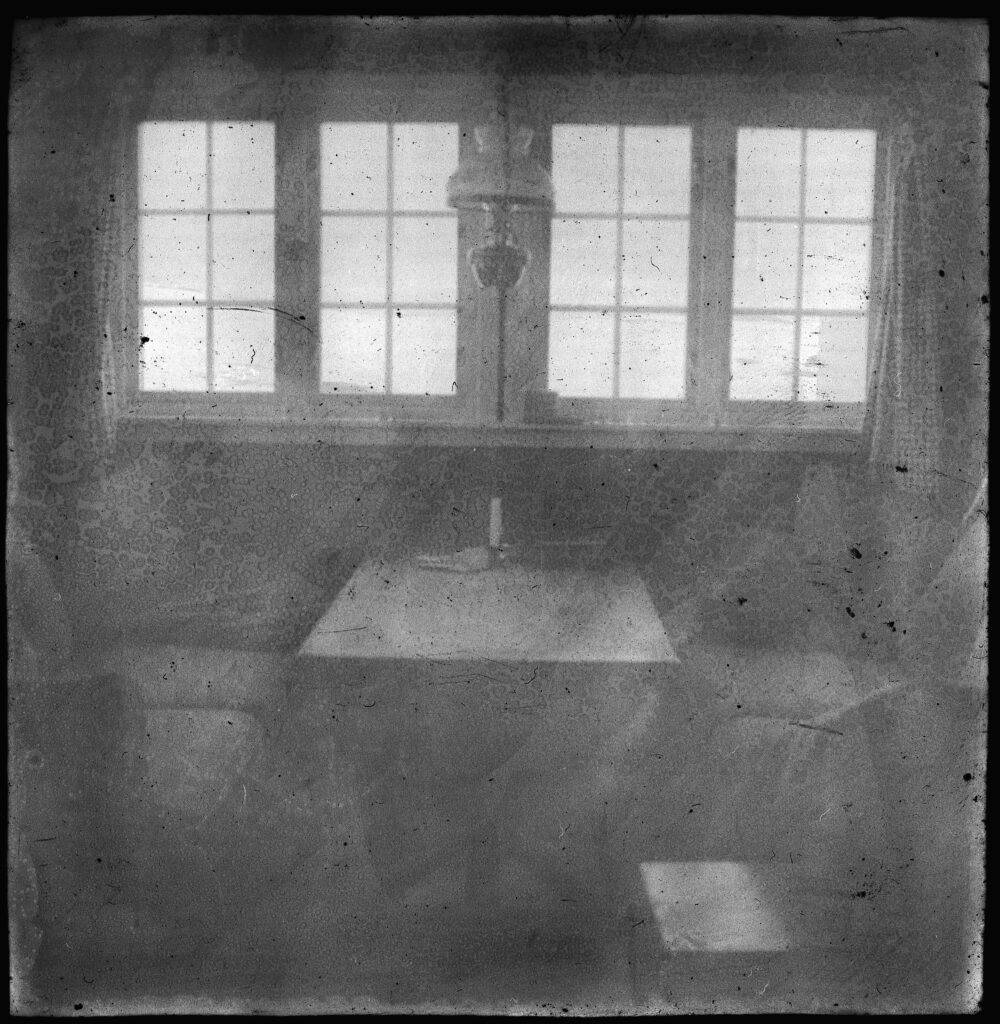

One process that caught my attention was emulsion lifting. In short, you basically cut open your exposed and developed integral film picture, pour hot water over it to detach the emulsion from the underlying developer paste and negative and then use a brush to rearrange the emulsion onto a piece of watercolor paper, all of which is easier said than done. And therein to me lies the fascination of this technique, the slight differences in the emulsions texture depending on the water temperature and the endless possibilities of rearranging the emulsion veil onto the paper surface is what put the hooks into me to keep experimenting with it. So fast forward to when the news arrived that I would have the possibility to revisit Svalbard, the path was set.

Snow, Coal and Airships:

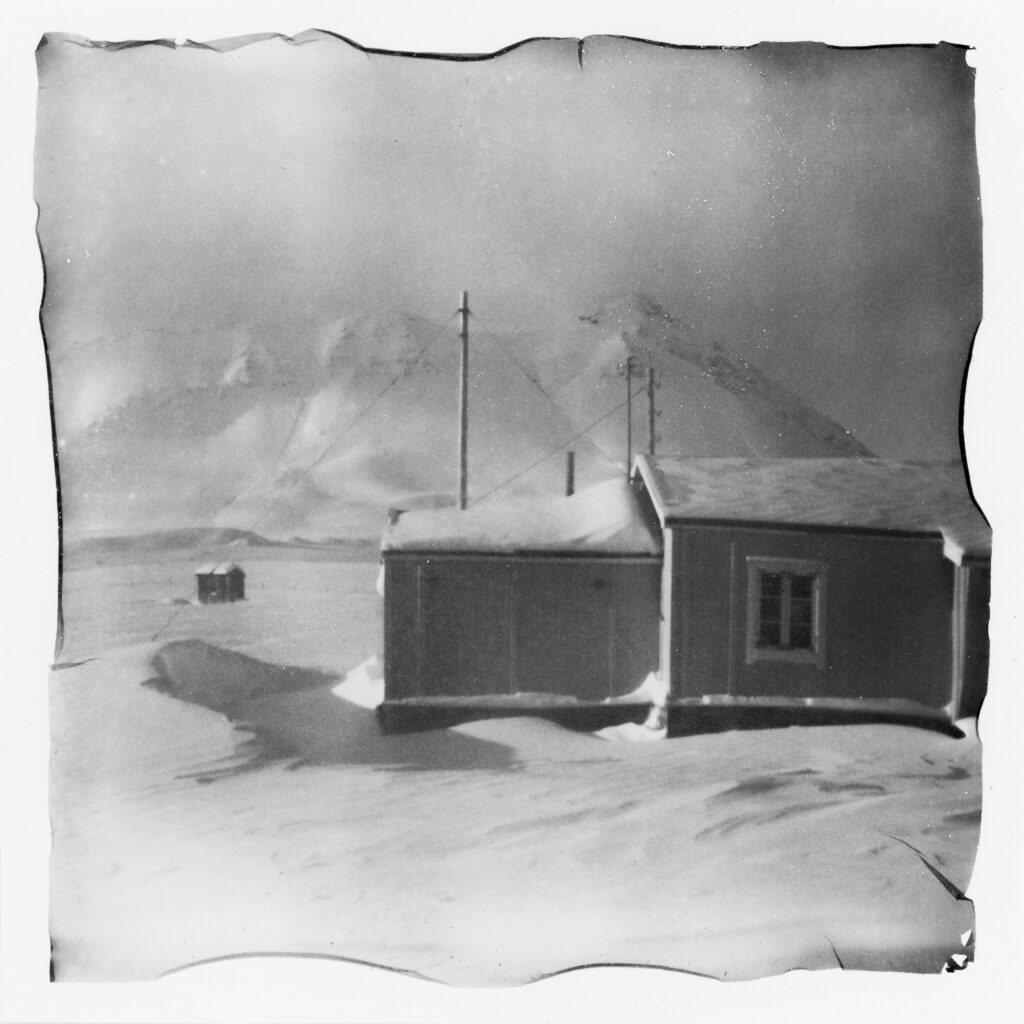

After four flights and 48 hours of travel, weather permitting, you finally touch down on an unpaved runway nestled along the shores of the Kongsfjorden. – but what’s different this time? You’ve reached the edge of the world: the doorstep of the world’s northernmost functional settlement. While there is limited accessed by for day-tourists by boats in the summer, it’s primary purpose is to provide researchers with a permanent base in the arctic and it is not accessible for the general public.

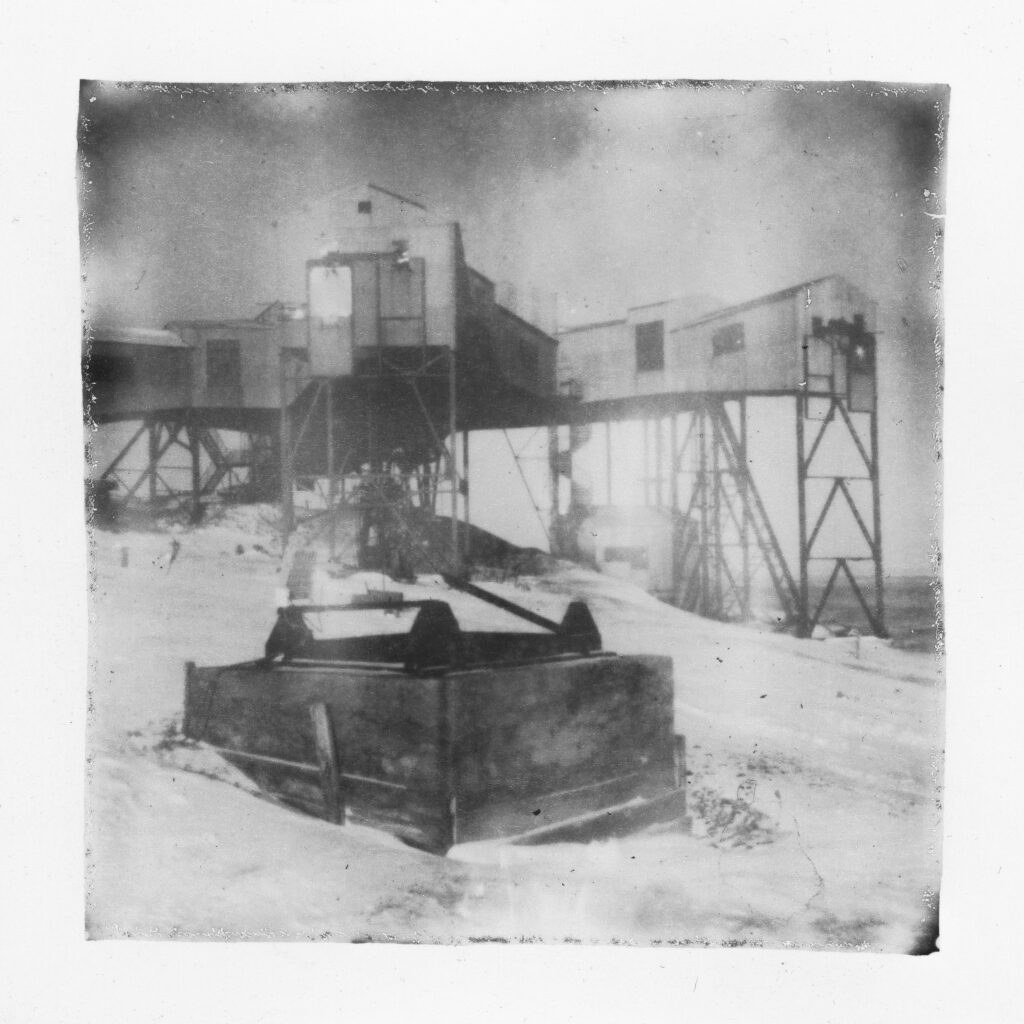

Here, there are no trees to mark the passing years with their rings. Only rocks, snow, and ice. Yet, the air is thick with memories. Discovered by an English whaler in 1610, the Kongsfjord remained untouched for another 300 years. The Kingsbay coal company was founded here in 1916, with the first inhabitants being coal miners who arrived over a century ago. The geology of the mountains around the Kongsfjorden is rich in coal, but also dangerous. The nearly vertical seams tend to accumulate methane gas and many people were lost in explosions and other mining related incidents. Between 1916 and 1963 alone 82 miners lost the live beneath the earth.

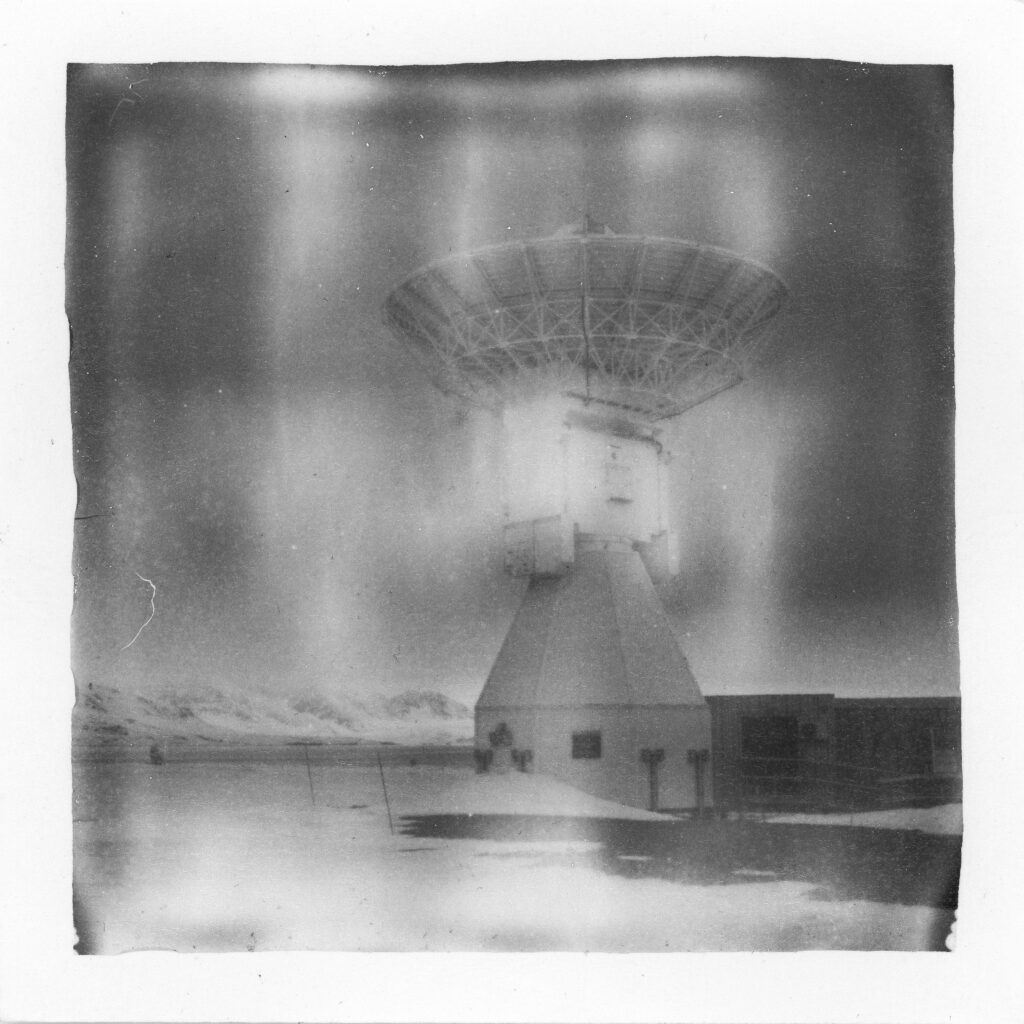

During WW2 Svalbard became strategically important and the remaining population of Ny-Alesund was evacuated. Even though the town was repopulated and modernized after the war, mining stopped for good after a tragic accident in 1962 costing 21 lives. A few years later the mostly abandoned settlement started attracted the first researchers and in 1965 the construction of the ESRO satellite telemetry station begun. Increased demand over the following decades led to more and more houses being renovated by the Kingsbay Company and 1989 a permanent regular flight between NYR and LYR where established, marking the beginning of this place as a permanent research base in the Arctic.

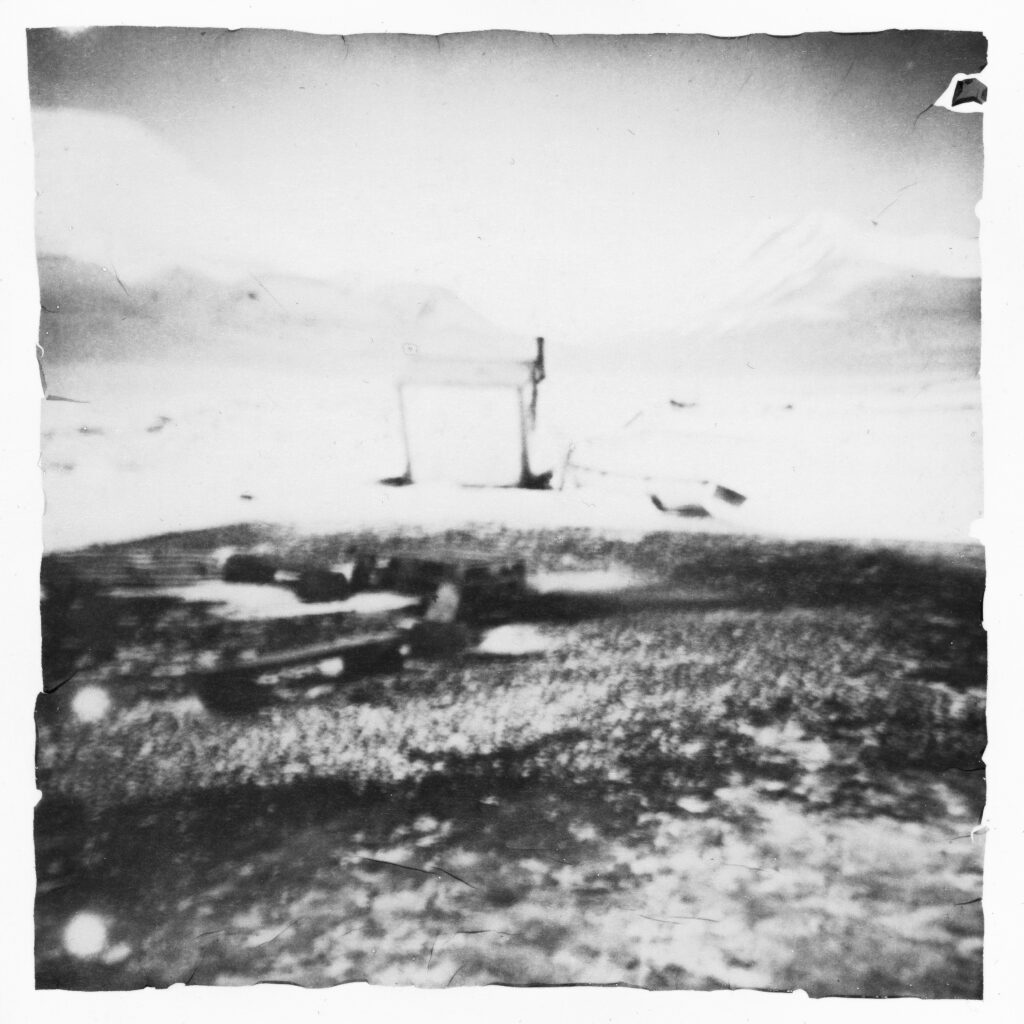

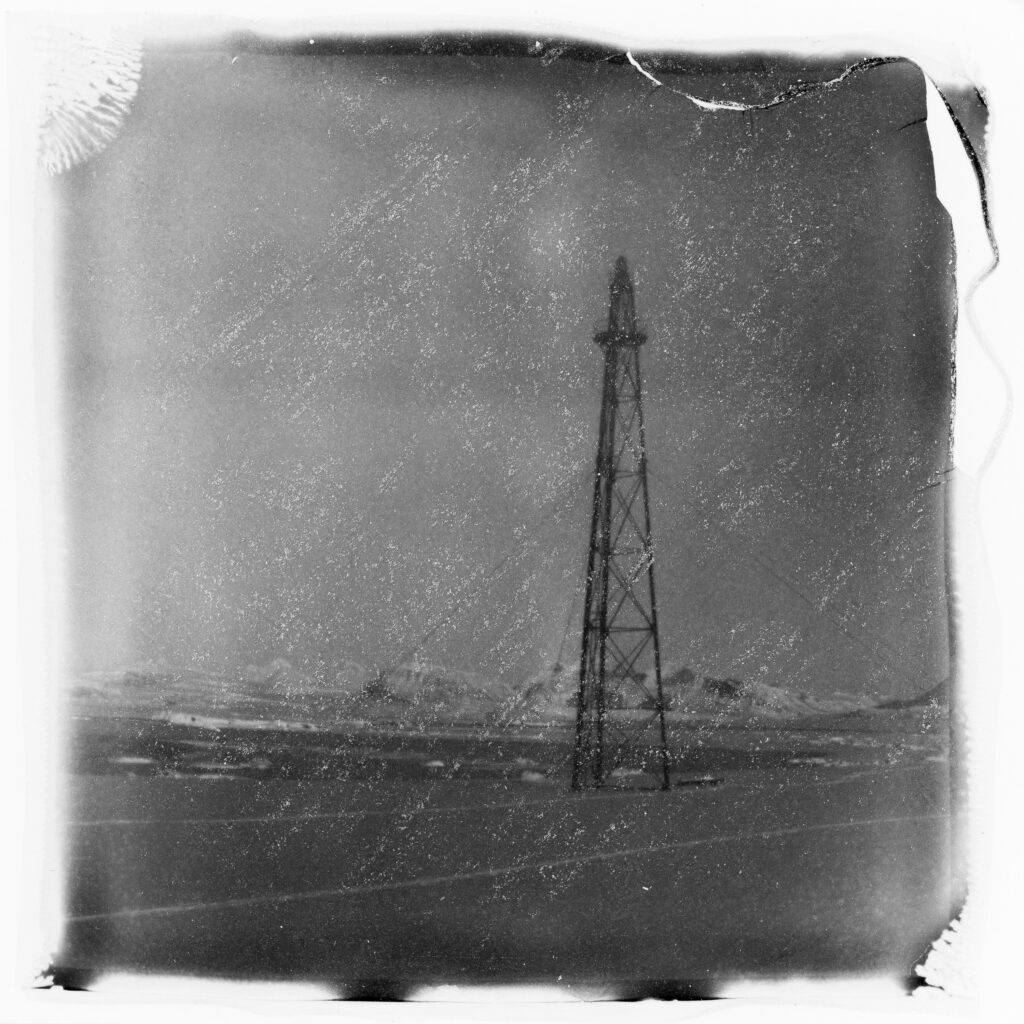

At the beginning of the 20th century, many polar explorers choose Ny-Alesund for the same reason we are here today: a safe harbor, relatively mild and shielded climate and the last solid piece of land before the north pole. In May 1926, the Italian-built airship Norge made history by becoming the first craft to reach the North Pole, piloted by Umberto Nobile, Roald Amundsen, and their crew. The docking mast of the airship, along with numerous pictures scattered throughout the village, serves as a reminder of this historic flight.

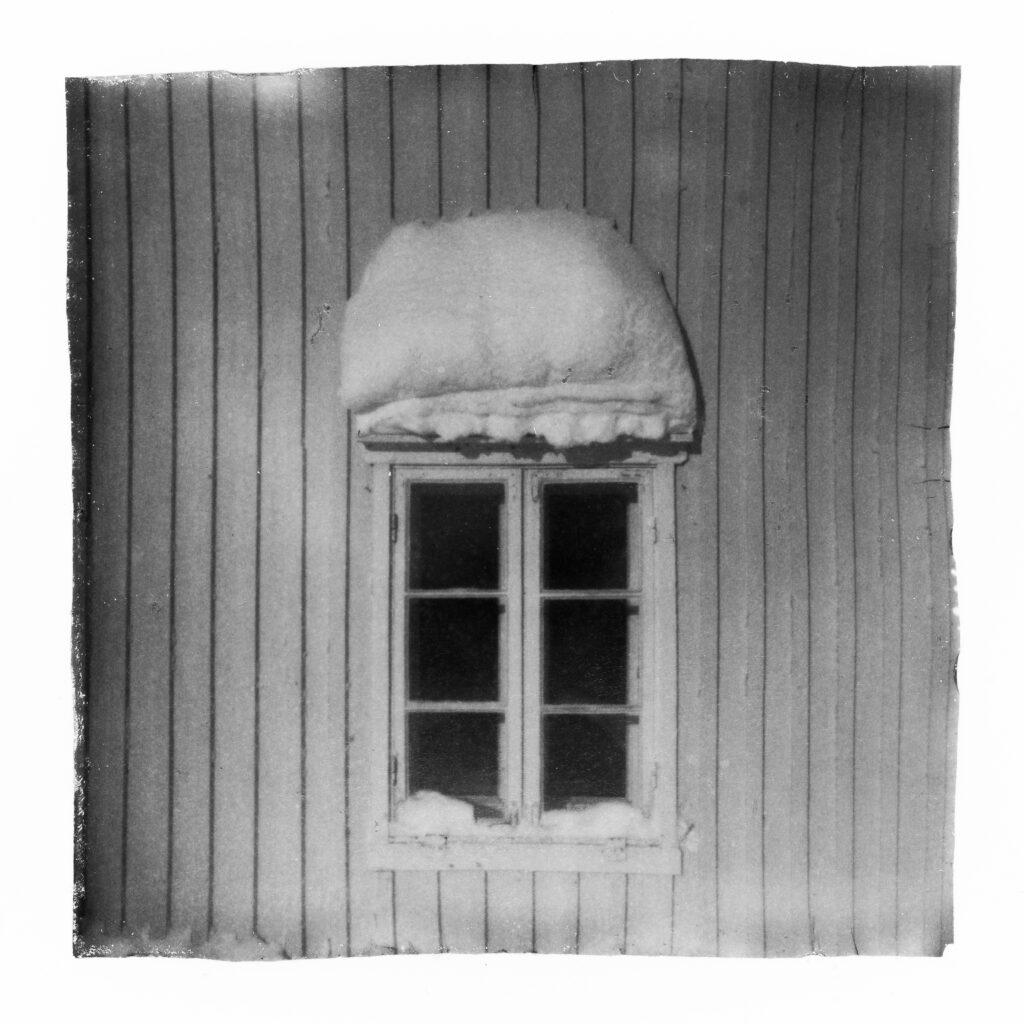

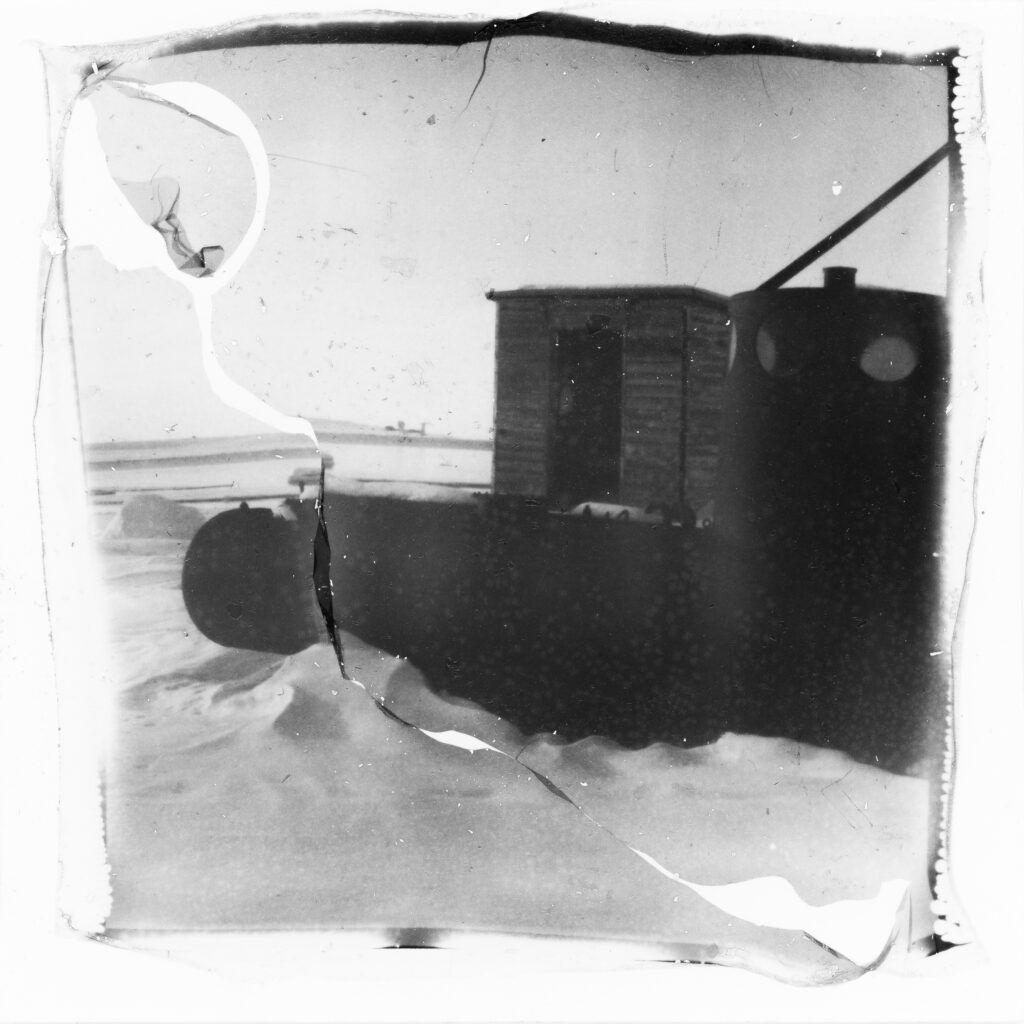

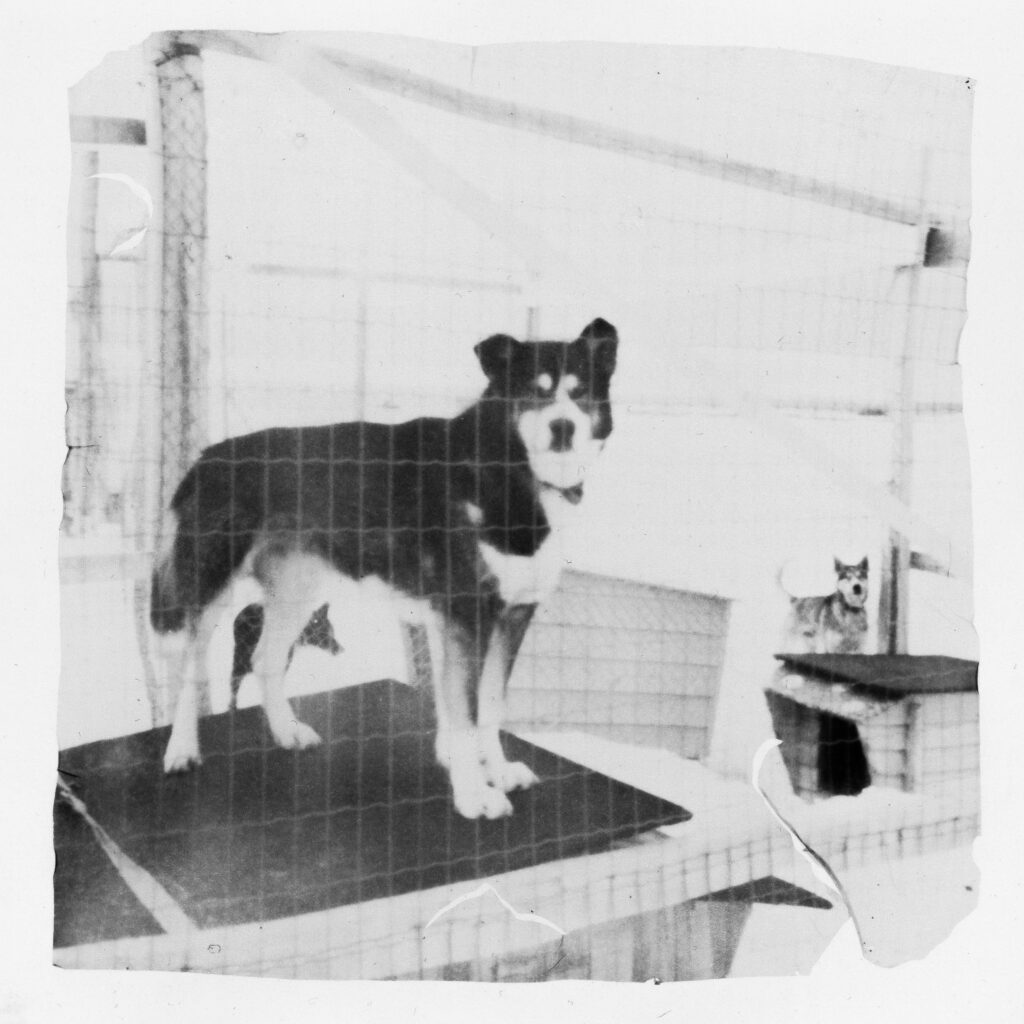

One topic that fascinates me is how humans over the course of the decades managed to live and make themselves a home in this seemingly hostile and remote environment. With short summers and cool, dry air, much of the old infrastructure, huts, and mining equipment from centuries past still stand, serving as a testament to the rich heritage of this remarkable place.

(Mildly Interesting) Side Notes:

I’ve written about the associated difficulties that come with shooting in the cold and harsh conditions of the arctic winter before – so no need to repeat myself – they also apply here. One additional problem I encountered with Polaroids is that you really need to try to keep your camera and film warm at all times, and I mean: at all times! Otherwise, the cold will on the one hand side reduce the viscosity of the developer paste resulting in an uneven or incomplete spread across the image and on the other hand slow down the development process to a point where your images all look extremely overexposed with almost all image details being blown out. I’ve included one example below so you get the idea, at that point I was already aware of the effect and overexposed the shot by 1.5 Stops (the maximum the SX-70’s dial will allow for) and yet the image has next to no visible information.

Over the time I got used to keeping the pictures and camera reasonably warm – these little handwarmers that react with the ambient air and are meant to be put in gloves and shoes do help a lot. Sometimes you might find yourself coming back in with a picture that still has a slight bluish cast from being not yet fully developed due to the cold. In that case you can submerge the picture in warm water or place it in a radiator which will help finish the process.

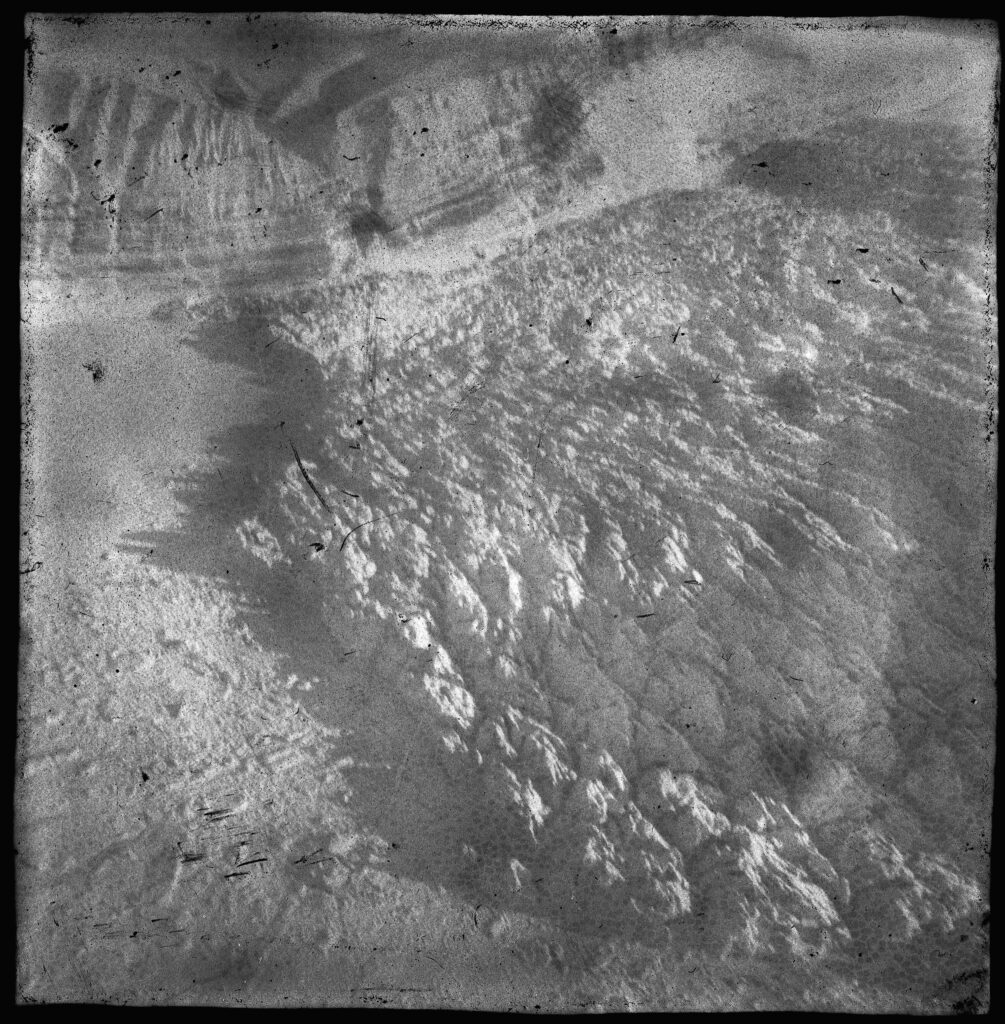

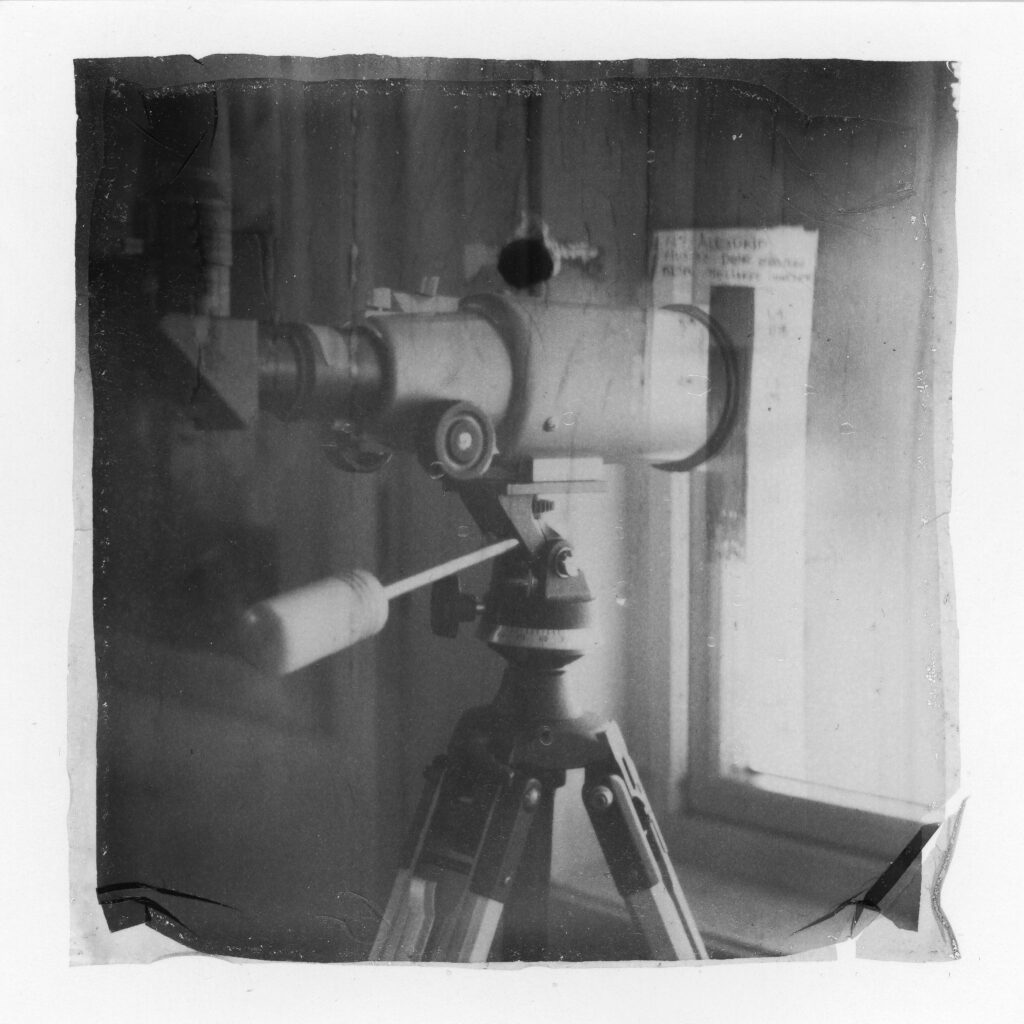

At some point in the process, I wondered whether you could use the inevitable negatives that you usually discard of as a byproduct for something. Back in the good old days there where some specific peel apart pack film types which were meant to yield a negative from which you could remove the opaque black coating and use it for printing in an enlarger. Unfortunately, this is not possible with integral film. However, you can clean the integral film negative from any residual developer past using warm water. Then after drying, tape it onto the glass of a flatbed scanner, scan it and e.g. manually invert it in Lightroom to reveal “the image”. While the whole thing kind of works it’ll give you a somewhat mutilated version of your lifted positive image as the hot water and mechanical aberration of the emulsion lifting process cause wrinkled grain structure, scratches and dirt spots. I included some of the less beaten-up specimens down below so you can judge for yourself.

Personal thoughts:

The last couple of months are somewhat representative for my ambiguous relationship towards the format. I’m thankful that integral polaroid film is still around and we can still use all the amazing cameras like the SX-70 and experience them. It’s just that I sometimes wonder whether the integral film will ever again get as good in terms of possible latitude, development times, color accuracy and number of shots per pack as the original Polaroid Time Zero Films once were. The shortcomings of the current film can also only partially be compensated for by the photographer, especially when you use cameras with automated electronic exposure control. As of now, I am not yet emotionally ready to sell one kidney but when time comes, I might opt for a SX-70 time machine modification by Mint Cameras in Japan, which would at least partially resolve some limitations of my current camera.

Wrap up:

So that’s that, take it for what its worth. I felt incredibly privileged to be part of this very close and interconnected community during my stay in the Arctic and I am thankful for having been able to experience the humbling and truly beautiful nature of this place. In terms of the emulsion lifting process and Polaroids – we’ll see where it goes. Even though I am a pure B&W shooter (as you can probably tell by now) I’ve started to partly paint/recolor some of my earlier emulsion lifts and I dig the look a lot, but that would be the topic of another piece. You have (almost) unlimited options – which is half the fun of the journey…

– Josh

Share this post:

Comments

Theodore Crispino on Instant Arctic – Emulsion Lifting on the Edge of the World

Comment posted: 30/07/2024

Peter on Instant Arctic – Emulsion Lifting on the Edge of the World

Comment posted: 30/07/2024

Neal A Wellons on Instant Arctic – Emulsion Lifting on the Edge of the World

Comment posted: 30/07/2024

John Furlong on Instant Arctic – Emulsion Lifting on the Edge of the World

Comment posted: 30/07/2024

Ben M on Instant Arctic – Emulsion Lifting on the Edge of the World

Comment posted: 30/07/2024

One question, did you have any issues with polar bears during your visit?

Comment posted: 30/07/2024

Ibraar Hussain on Instant Arctic – Emulsion Lifting on the Edge of the World

Comment posted: 30/07/2024

Everything is so extraordinary

Thank you

Really enjoyed it

Gary Smith on Instant Arctic – Emulsion Lifting on the Edge of the World

Comment posted: 30/07/2024

J. on Instant Arctic – Emulsion Lifting on the Edge of the World

Comment posted: 30/07/2024

Everything about this piece is remarkable - thank you so much for sharing it with us.

Steviemac on Instant Arctic – Emulsion Lifting on the Edge of the World

Comment posted: 31/07/2024

Scott Gitlin on Instant Arctic – Emulsion Lifting on the Edge of the World

Comment posted: 01/08/2024

Bill Brown on Instant Arctic – Emulsion Lifting on the Edge of the World

Comment posted: 01/08/2024

Uli Buechsenschuetz on Instant Arctic – Emulsion Lifting on the Edge of the World

Comment posted: 06/08/2024