Another Monday, another episode of my Pinhole Adventures series… but this one is a bit different. So far, I’ve mainly focused on designing and building cameras. Part 4 is less about cameras and more about the images they create; less about engineering and more about art.

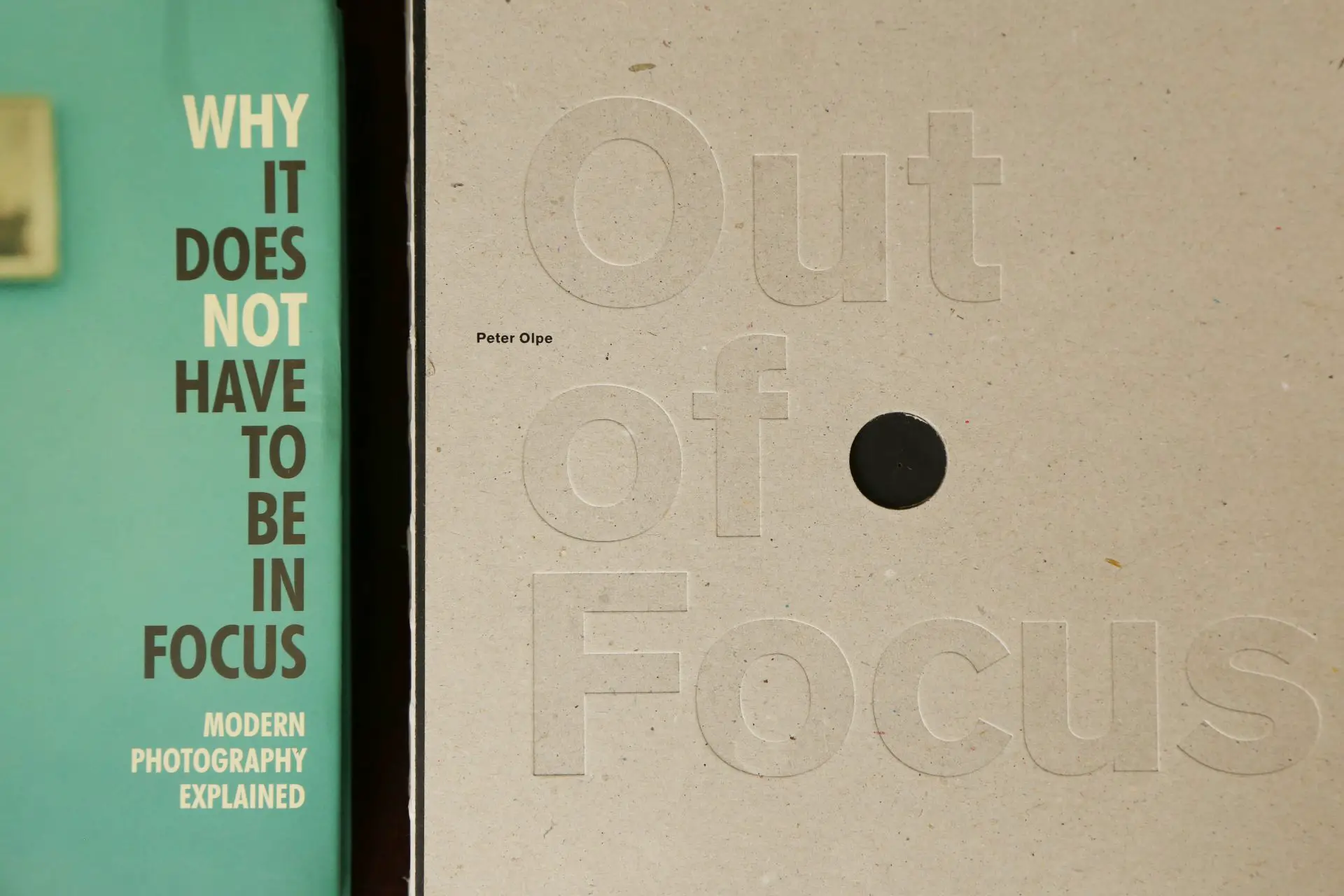

I’ll review two books, whose titles coincidentally mirror one another. The first is Why It Does Not Have to Be in Focus by Jackie Higgins. This book is about contemporary photography in general, i.e. not pinhole specific. But it’s certainly relevant to pinhole photography – compared to lenses, pinhole images are somewhat blurry, no matter how much you try to optimise them.

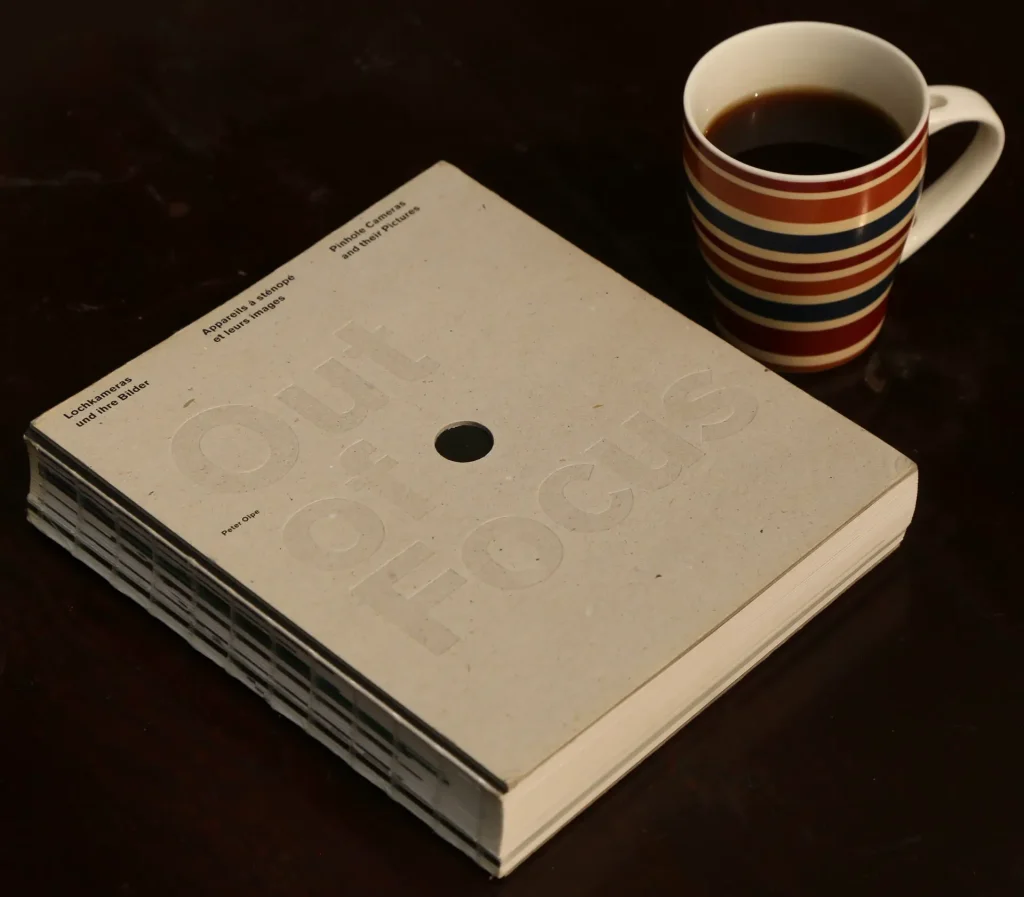

The second book is Out of Focus by Peter Olpe, a kind of coffee-table book of pinhole photography. It features Olpe’s elegant cardboard cameras (and you know how much I love cardboard cameras), as well as photographs by various artists made with those cameras, some essays and other sundries.

A quick note before I start – in both books, the paper and print quality are superb. I’ve reproduced a few pages in this review, and I’ve also linked to online versions of some of the photos in the books. But these do not really do them justice.

Why It Does Not Have to Be in Focus

Why It Does Not Have to Be in Focus: Modern Photography Explained by Jackie Higgins

Thames & Hudson, 2013, 224 pages (paperback)

You don’t have to be into pinhole photography to enjoy this book; I would recommend it to anyone who is interested in photography as an art form. Jackie Higgins presents 100 contemporary photographs and explains why they have artistic meaning and value – even though some of us might think of them as “bad” photos.

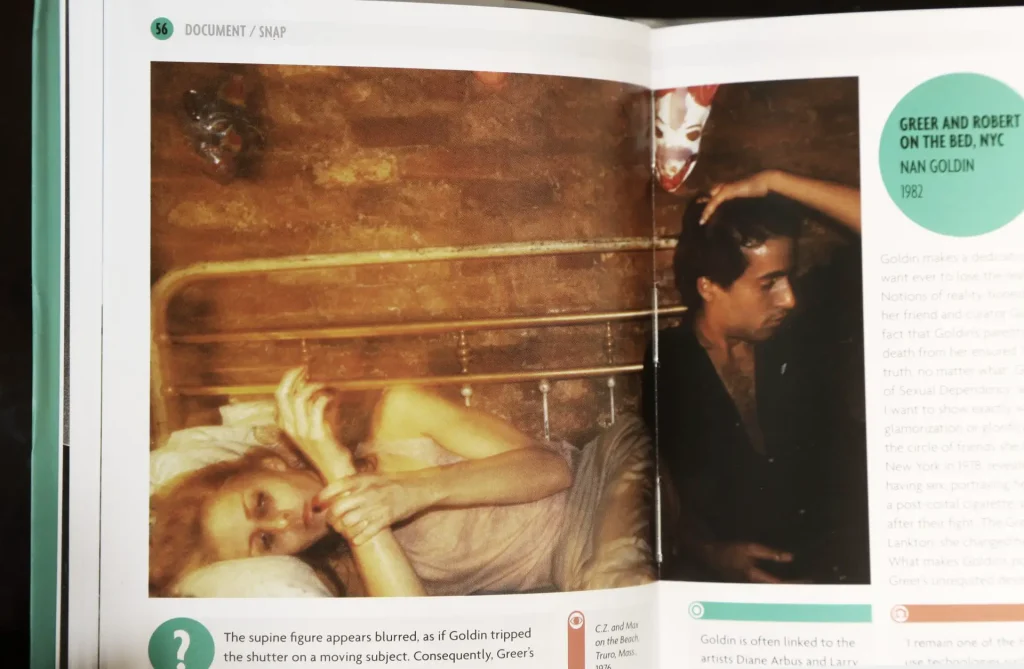

Some of the photos in the selection, like Uta Barth’s Ground #42 (featured on the cover, see above), are indeed out of focus. Others seem overexposed (Paul Graham’s American Night series), badly composed (John Baldessari, Wrong), damaged (Laurel Nakadate, Lucky Tiger #8) or simply banal (William Eggleston, Red Ceiling).

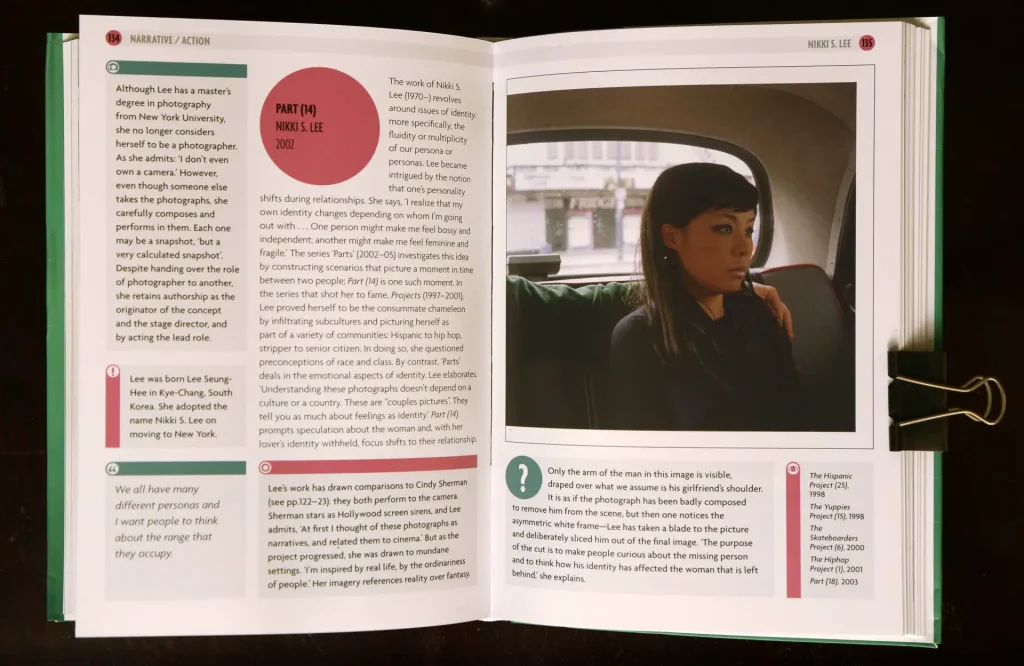

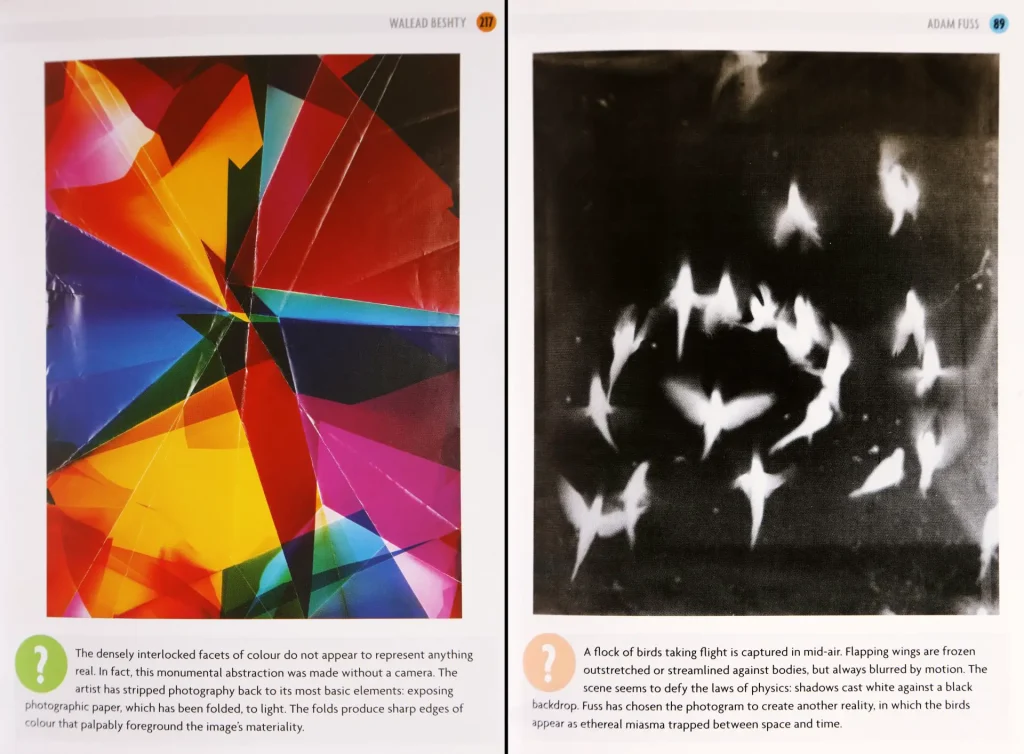

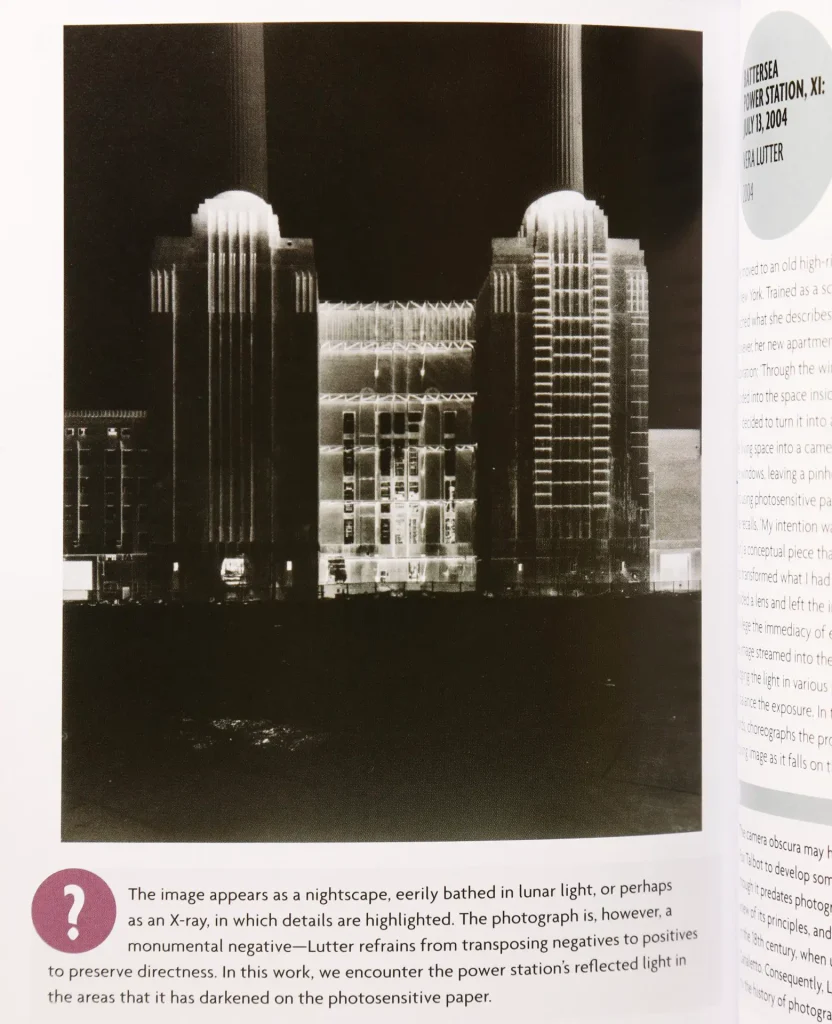

Each photo gets two pages. There is a reproduction of the photo itself, plus notes explaining why it is an important work of art as well as the artist’s philosophy and process, and other information.

As someone with no formal background in photography or art, I found the text really added my appreciation of the images. For example, in the photo by Lee (above), the asymmetric frame and its implications would have probably escaped my notice.

Sometimes, just sometimes, Higgins slips into art-crit jargon, like where she describes one artist as “perfectly placed to interrogate the ontological divide” between painting and photography. Fortunately, these lapses are rare; overall, the text is simple, illuminating and concise.

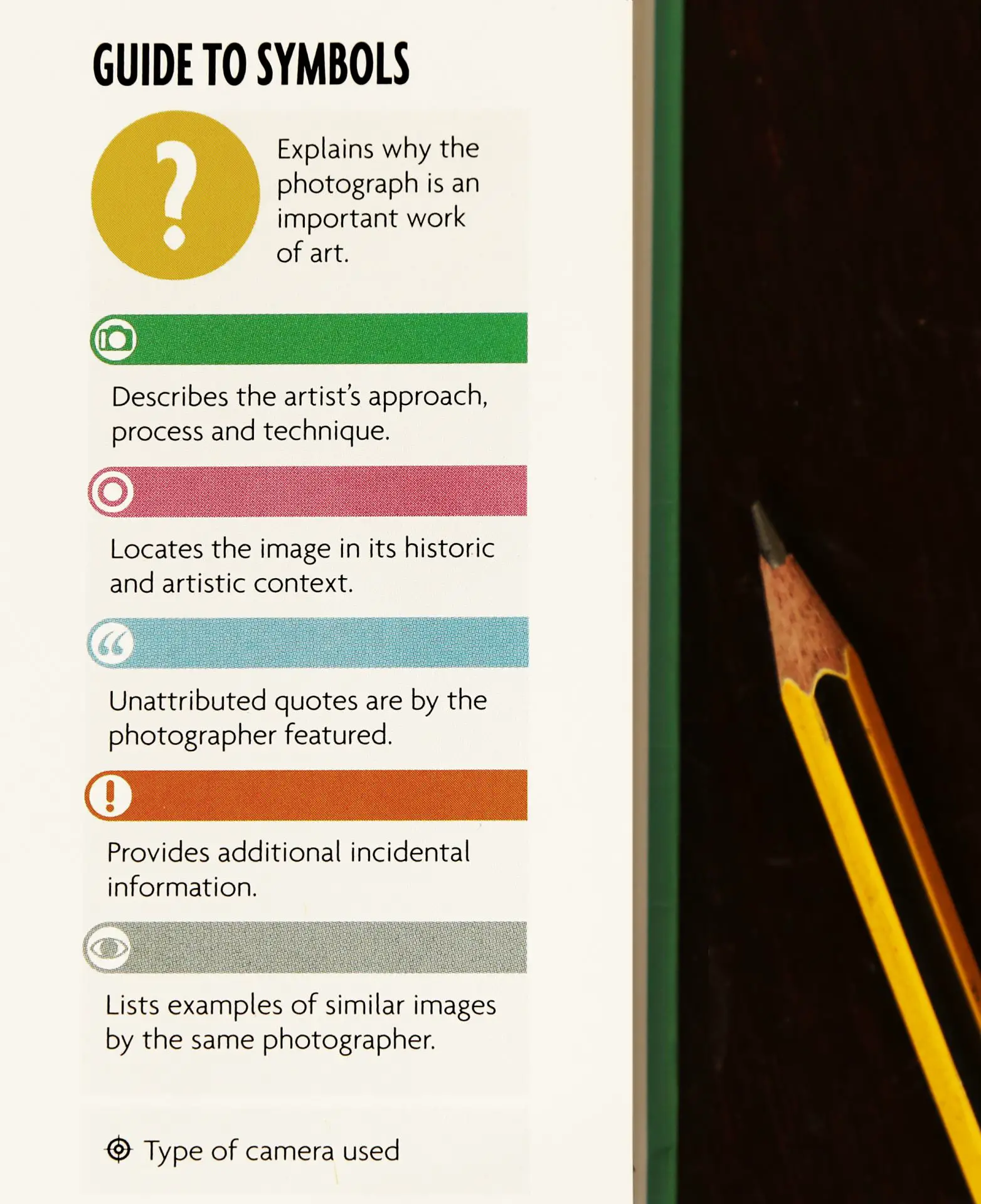

The information is organised under different sections (see the Guide to Symbols below). Personally, I would have preferred fewer sections, as the text sometimes feels a bit fractured. For instance, I think “approach, process and technique” and “historic and artistic context” could have been merged into the main text.

With the photos on the other hand, Higgins follows a “less is more” approach which works really well for me. Each two-page entry carries just one photo. It must have been tempting to include photos of some of the more interesting processes and cameras used to create the images, or other examples of the artist’s work, but ultimately that would have distracted from the main image.

And each artist gets just one entry, though there is a short list of other works for further exploration. The selection is sometimes iconic (like Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare) and sometimes surprising (Daido Moriyama’s uncharacteristically serene Love Motel). But this is not a criticism – Higgins is obviously neither trying nor claiming to represent an artist’s entire body of work through a single image.

The strength of the one-photo-per-artist approach is that it lets us sample the work of many different artists. There are some legends of 20th century photography – Lee Friedlander (Self-portrait) and Sally Mann (Amor Revealed), to name just two – as well as younger artists like Sohei Nishino (Diorama Map), and even some who are better known for their work with other artistic media, like Danish–Icelandic sculptor Olafur Eliasson (Jokla series) and Iranian film director Abbas Kiarostami (Rain).

The book is organised into six chapters: Portraits, Document, Still Lifes, Narrative, Landscapes and Abstracts. One reviewer called this categorisation “the most problematic part of the book” but it works for me. Of course, it means that artists who share similar philosophies or processes can get pigeonholed into different chapters: Walead Beshty’s Six Sided Picture and Adam Fuss’s Untitled are both cameraless photograms, but they appear under Abstracts and Still Lifes respectively. Personally, I don’t mind this at all – it’s fun to spot these unexpected connections and affinities, and a nice reminder that art can never truly be confined to the neat little boxes we devise for our convenience.

Within each chapter, photos are presented chronologically. The book’s subtitle is Modern Photography Explained, but it’s not quite clear where the line is drawn line between what’s modern and what is not. The newest photo in the book is Wolfgang Tillmans’ Freischwimmer 204 (2012), just one year older than the book itself, but the oldest is Cartier-Bresson’s Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare (1932) – and not everyone would classify 1932 as “modern”. On the other hand, if modernity is defined not by age but by innovation or pushing the boundaries of art, Eugène Atget’s photos of Paris from the early 1900s and Germaine Krull’s dizzying Métal studies from the 1920s (neither of which are in the book) are as modern as they come.

But that is a minor flaw – if it can be called a flaw at all. My only real criticism is to do with the overwhelming preponderance of artists from western Europe and North America (and to some extent, Japan). For instance, I don’t believe there is a single artist from Africa, South Asia or the post-Soviet states featured in the book. It’s not that contemporary photography is not practised in other parts of the world – consider the work of Fatoumata Diabate (Mali), Santu Mofokeng (South Africa), Sohrab Hura (India) or Uldus Bakhtiozina (Russia), to take just four examples. This, to me, is a surprising and disappointing omission, and the sort of thing which only serves to entrench the art world’s deep-seated western bias.

In other ways, the selection is admirably diverse – female artists are well represented, as are a variety of artistic processes and philosophies. And speaking of processes – since I’m ostensibly reviewing the book as part of my pinhole series, I would be remiss not to mention that pinhole photography is also represented (yes!) in the form of Gábor Ősz’s Travelling Landscapes and Vera Lutter’s Battersea Power Station.

These two pictures were made with the largest of large-format cameras: Ősz turned a moving train compartment(!) into a camera obscura, and Lutter (below) did the same with a shipping container.

On the whole, and despite some of my reservations about the selection, I would recommend this book if you’re interested in photography as art, or even contemporary art in general. It’s an inexpensive book, but with high production values. It has taught me a lot about the medium, and perhaps even made me look at photographs differently. It’s not the type of book I would read from cover to cover in a single sitting, but I keep it on my shelf to frequently dip into – and to be surprised, provoked and inspired.

Out of Focus

Out of Focus: Pinhole Cameras and their Pictures by Peter Olpe

Niggli Verlag, 2013, 432 pages (hardback)

“I like the idea of bartering” says Peter Olpe, Swiss graphic designer, photographer and illustrator, “because it creates a certain kind of intimacy … One has to remain open to the other person. In money transactions this is not necessary – or perhaps is even a nuisance.”

In the autumn of 2009, Olpe hit upon the idea of an “art barter”. He had been making cardboard pinhole cameras since the 1970s, and for a few years in the ’90s, even selling them. Now, he got the idea to send some of his cameras to friends, acquaintances and strangers. The deal was that they could keep the cameras, so long as they sent him at least three images which (if he liked) he could publish in a book.

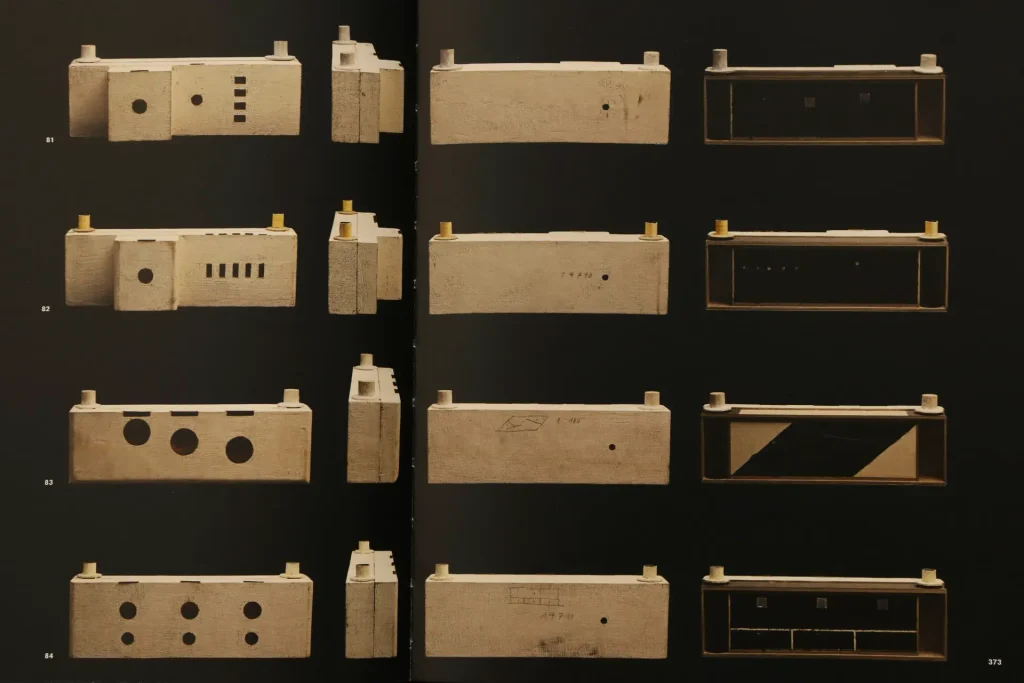

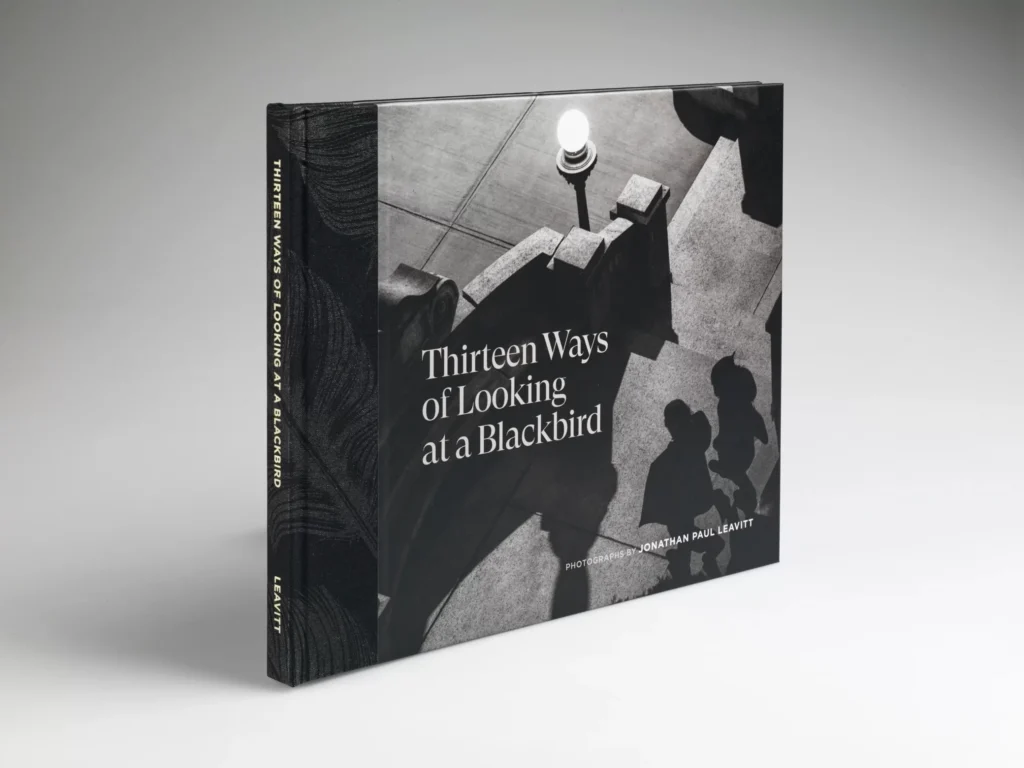

Out of Focus presents the work of 39 photographers, all made with Olpe’s cardboard cameras. These photographs comprise the book’s first part, titled “Viewpoints”. The second part, “Workshop”, documents Olpe’s background as graphic designer, illustrator, maker and user of pinhole cameras. The third and final part, “Archive” introduces 90 of his cameras which he donated to the Swiss Camera Museum in Vevey.

The book was originally designed as a catalogue for an exhibition hosted by the Camera Museum in 2012, to celebrate the addition of Olpe’s cameras to their collection. But with over 400 beautifully designed and printed pages, it feels much more substantial and lavish than a typical catalogue; in fact, it won a silver award at the 2013 Deutscher Fotobuchpreis (German Photo Book Prize).

Now I like both cardboard cameras and non-capitalist forms of exchange, so you’d think this book would be right down my alley. And I do like it… if not quite as much as I had hoped. Maybe I set my expectations too high!

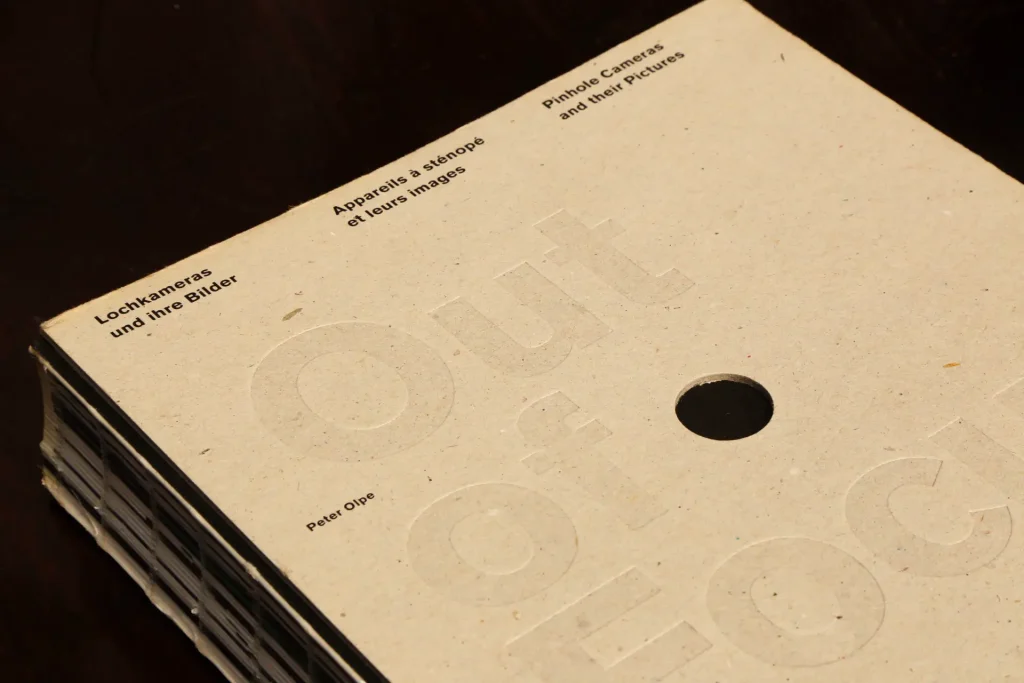

The book has a pinhole on the front cover, which is immediately endearing. And as you can see from the text at the top, it is trilingual. For the most part, German, French and English text appear side by side. Some of the longer passages of text, like the essays, appear first in German, with French and English translations at the end of the book.

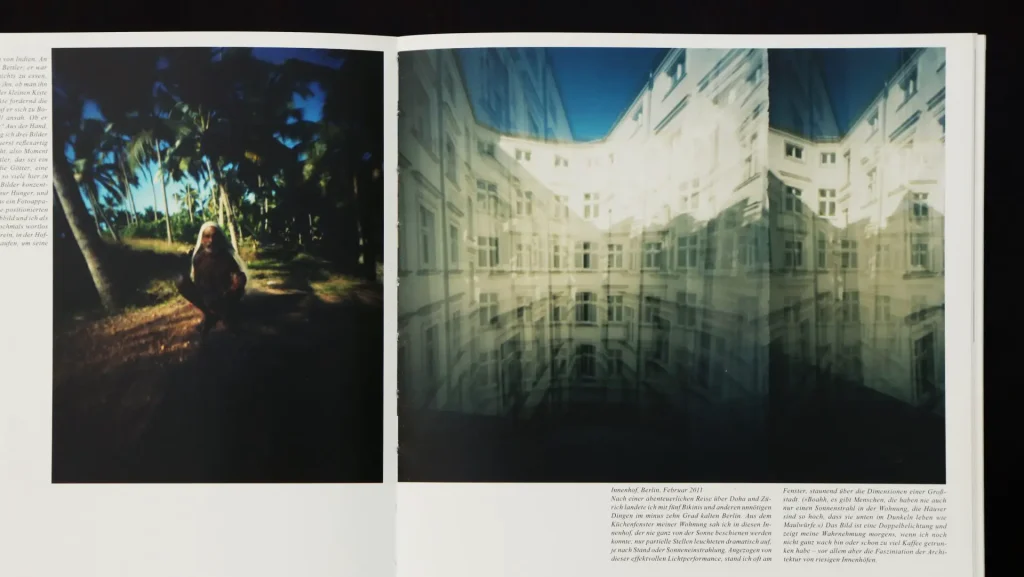

Part 1 (“Viewpoints”) features the work of 39 photographers who took part in Olpe’s art barter. Each of them gets at least two pages; some get as many as eight. Some of the photos are printed relatively small with pleasing use of negative space, while others get a full page, a double page or even, in one case, a foldout. Besides the photos, each entry has a brief artist bio, plus a small photo of the camera they used and its particulars (film format, focal length, f-stop and pinhole diameter). The layout is elegant and minimalist; Olpe is, after all, a graphic designer – and a Swiss one at that.

A few photographers also added their own reflections and anecdotes, and I found these quite charming, showing some of the traits I’ve come to associate with pinhole photographers everywhere: a capacity for wonder – “Look how the chandelier is burning way up there! Look how far beneath you the shining cobble stones lie!” (Clemens Klopfenstein) – and a sense of the absurd – “After an adventurous journey via Doha and Zurich I landed with five bikinis and other useless objects in Berlin, where it was minus ten degrees” (Ruth Erdt).

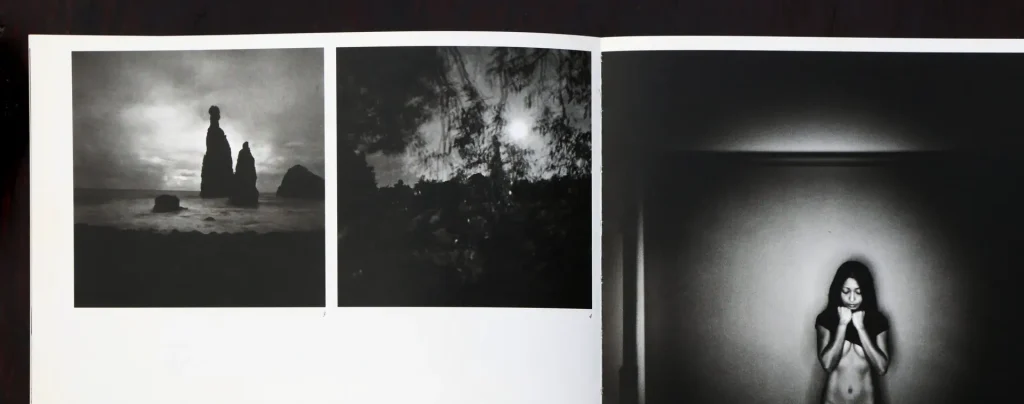

This part has some images which I really like, but I must say there were several others which did not really speak to me. Now this is just my opinion – I have no formal background in photography, and of course, art is subjective. But when I first discovered pinhole photography not that long ago, I was enamoured by the blurriness, the vignetting, the ultra-wide angles – everything looked amazing. Whereas now I find myself looking for images which, to me, offer something more than just the “pinhole aesthetic”.

I do get that elusive “something more” from some of the contributions. Ruth Erdt’s Berlin photo is at once light and sunny, but also disorientating and vaguely sinister. Christian Vogt (above) makes captivating monochromes of real landscapes and people. At the other extreme, Bethany de Forest (below) uses everyday objects to construct hyper-saturated fantasy landscapes and lifeforms, like Avatar on acid.

But several other photos, as I say, left me relatively unmoved. To be fair, I suppose the main point of this book is showcasing Olpe’s cameras, and photos taken with those cameras. Moreover, from the artists’ perspective, it’s a tall order to get a pinhole camera in the post and instantly start producing exceptional work. Most of Olpe’s collaborators were photographers or artists, but many had never used a pinhole camera before. And even if you have, it takes time to get used to a new camera and its “way of seeing”, especially since most pinhole cameras don’t even have a viewfinder.

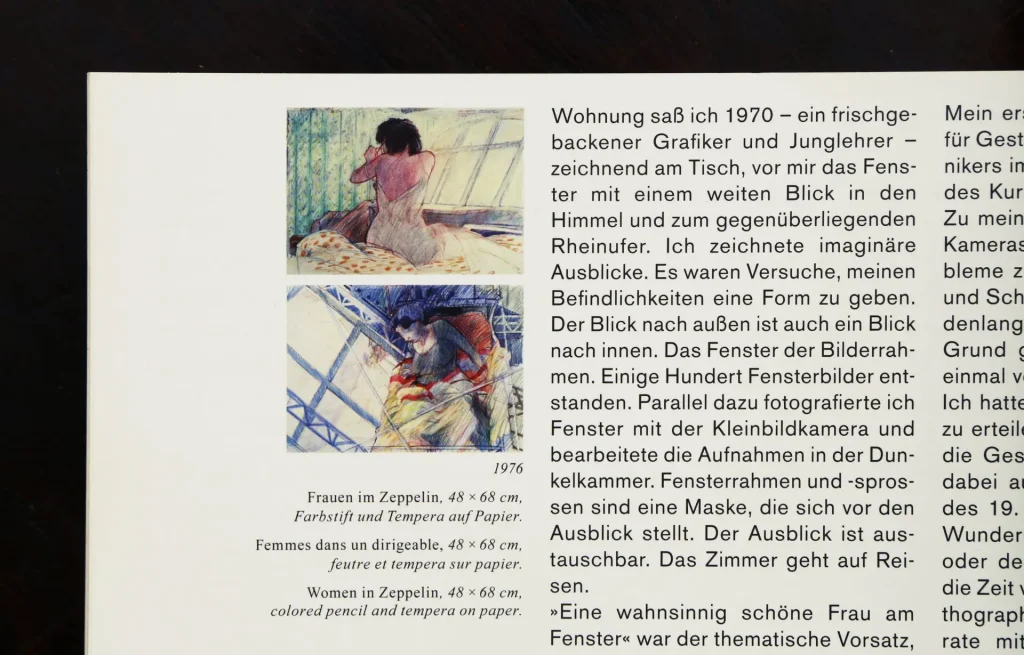

Part 2 (“Workshop”) is about Olpe’s work as designer, illustrator and teacher, and how he got into making and using pinhole cameras. It’s presented through an eclectic mix of essays, drawings and photographs.

Olpe writes engagingly, and with self-deprecating humour, on a variety of topics – his offbeat projects (he coupled a 16mm movie camera to a bicycle chain, which films the cyclist when they pedal), his funny superstitions (the front of a camera is painted “to attract pictures to it”) and what makes him tick (“I love creating things with my hands. This is the simple truth.”) The images which accompany the essays are pretty small, and I found myself wishing they were printed bigger – but this is only a minor complaint.

Part 3 (“Archive”) showcases the 90 cardboard cameras which Olpe donated to the Swiss Camera Museum. They have a similar design aesthetic – geometric, clean and minimalist (even when they are painted to resemble castles or Swiss cheese). The cameras are beautiful – the museum directors call them “these wondrous boxes of light” – but the laconic descriptions left me wanting to know more.

For example, the entry for Camera 82 (second from top) only gives the film format, focal length, pinhole diameter and f-stop. But the camera clearly has multiple apertures – what are they for? What kind of images does it take? Unfortunately, I can only guess. It would be nice, too, if Olpe included instructions for building a couple of his cameras. They are beautiful objects, as I say, but the way they are presented encourages us to see them only as objects.

Would I recommend this book? Maybe, if you’re into pinhole photography. It’s a relatively expensive book, and if you ask me whether it was it worth it, I would say yes… but not a resounding yes. Then again, I am me, and you are you. So who knows. Now if that’s not the most unhelpful book review conclusion ever, I don’t know what is.

Oh and before I end, thanks to my friends Jeff and María, from whom I learnt about these two books. Have you read either of them, or do you have any other photobook recommendations? Please let me know in the comments! And if you’re on Facebook, you’re also welcome to join our new group called Photography books and theory. Thanks for reading, and see you soon for the next instalment of Pinhole Adventures.

Share this post:

Comments

Kate on “Why It Does Not Have to Be in Focus” and “Out of Focus”: Pinhole Adventures Part 4 – by Sroyon

Comment posted: 30/11/2020

Comment posted: 30/11/2020