When I first started collecting photobooks, one of my first was Spomenik by Jan Kempenaers. It wasn’t so much the photographs that drew me in, it was the brutal and futuristic structures in the photographs. Amazingly, you can see the whole book here. At the time,I didn’t know what or where they were and the book was quite enigmatic. I eventually learnt that the term is Serbo-Croatian/Slovenian for *monument* and that they are all located in the former Yugoslavia.

The book then sat on the shelf for a bit, as they do. Biding its time. Fast forward a few years and I was browsing for a film (movie) to watch on the BFI site, sort of scrolling through the sci-fi list when I came across one titled Last and First Men. I stopped because I knew the book. And if you’re a sci-fi aficionado you’ll probably know it too. It’s quite a book. Written by Olaf Stapledon in 1930 (I kid you not) it tells the story of humanity across the next two billion years. The film I stumbled across was a posthumously released interpretation from 2020 by Icelandic director Jóhann Jóhannsson (1969 ‑ 2018). When I started watching the film, I instantly recognised the structures that the film used to tell the story as Spomeniks: the mesmerising, brutal, stark monolithic entities I knew from the photobook. A magical and serendipitously circular link had been made in me.

The whole subject then came back to me when my wife and I started planning a trip to the Balkans. It dawned on me that where we were going was the home of the Spomeniks. I dug the book out and mapped all the documented monuments onto Google maps. Many were in countries we were not going to visit (Serbia, Montenegro…) but quite a few were. We agreed that we would visit as many as many as were practical given that we were in a motorhome with a dog.

In the end, we visited eight. And this is the story of some of the photographs. Part 2 will follow shortly.

What exactly are Spomeniks and why do they look like they do?

These are big questions and the best way to learn more is to read the excellent, well-researched and informative articles on the Spomenik Database. But here’s an attempt to summarise the topic in a couple of paragraphs…

They are a legacy of the former Yogoslavia which had a huge desire after WW2 to establish an optimistic, forward looking and non-partisan series of monuments dedicated to WW2 battles and atrocities. They were very consciously designed to distance Yugoslavia from the Soviet figurative socialist-realist design imperative. Yugoslavia broke away from the USSR in 1949 and became an independent country. It then de-emphasised its Soviet links while emphasising those to the West, including its minimalist, abstract expressionist, and surreal art movements. This is why Spomeniks are abstract and not bronze figures holding hammers, sickles and rifles.

Spomeniks were frequently commissioned via open or closed competitions as a vision of a modernist and futuristic society of a ‘new tomorrow’. Traditionally, monuments were perceived as being invisible. Conversely, Spomeniks were conceived as a mechanism to initiate thought, engagement and looking forwards when being confronted with a monument to the past, they symbolised a vision of a future shaped by collective unity and universalism. This is why they are so bold, striking and large.

It’s also worth pointing out that while there are Spomeniks you might stumble across, the majority require seeking out. They’re not hidden, but they are often in somewhat obscure, but generally easily accessible, places.

Ilirska Bistrica, Slovenia

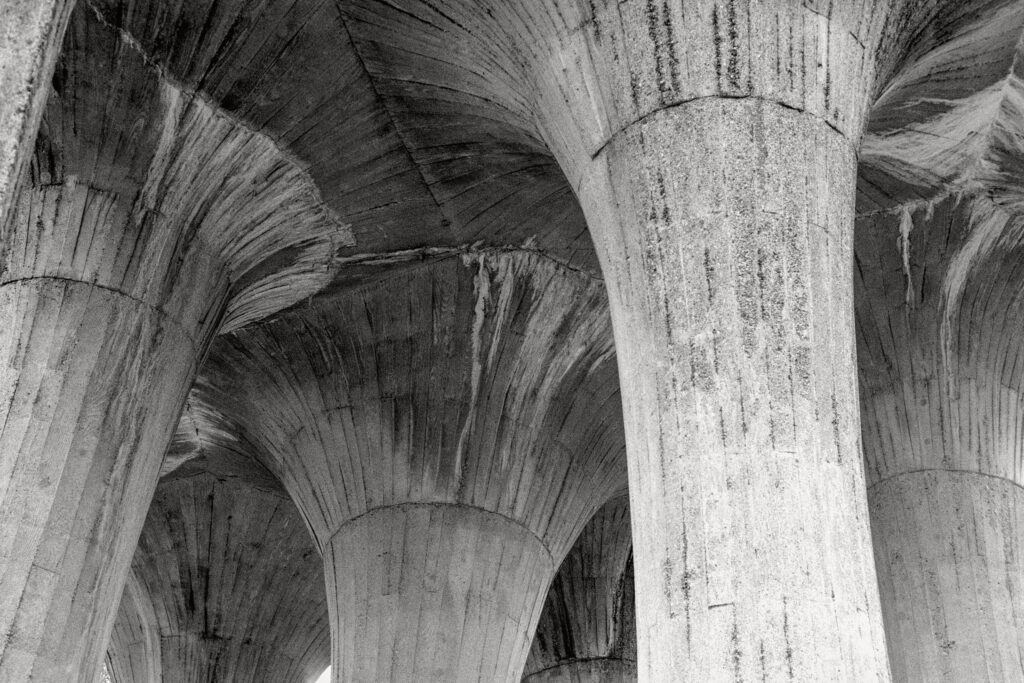

This is a small town, almost a village and the memorial is in a beautifully landscaped park right in the centre. We parked in a side street, walked into the park and saw the poured concrete structure emerge into view. It’s striking, beautiful, and breathtaking (as are many Spomeniks). Nothing prepares you for seeing such a modernist edifice in an unassuming park in a provincial town in Slovenia. Until, that is, you realise that the former Yugoslavia contains tens of thousands of such monuments.

The park was deserted save for the odd dog walker or two and the occasional shopper using the park as a short cut. As a structure, it was designed to reflect the limestone columns present in the nearby caves. What strikes you is the audacity, the vision, the desire to build something that would make people stop and think. I found it amazing that there was no information of any kind nearby as to what it was commemorating.

When you know though. When you know what this monument is about. When you stand and look and think and engage. And think. It’s a different experience. It’s actually an experience. It’s not like coming across an almost invisible bronze statue on a plinth; instantly forgettable and dull. This complicated, intricate and thoughtful monument stops you in your tracks.

I won’t try and explain the purpose of this monument. I encourage you to read this which includes beautiful period images relating to its construction and social history.

I’m not sure how this series will pan out – we visited eight Spomenik sites and I took many photographs. Many of the monuments have been vandalised or destroyed in or since the Balkan wars of the 1990s.

I’m on Insta and I have a website too.

Share this post:

Comments

Cem Eren on The Balkan Spomeniks – Monuments for a new tomorrow

Comment posted: 30/11/2024

Comment posted: 30/11/2024

Geoff Chaplin on The Balkan Spomeniks – Monuments for a new tomorrow

Comment posted: 30/11/2024

Great shots too!

Comment posted: 30/11/2024

Art Meripol on The Balkan Spomeniks – Monuments for a new tomorrow

Comment posted: 30/11/2024

Comment posted: 30/11/2024

Peter Roberts on The Balkan Spomeniks – Monuments for a new tomorrow

Comment posted: 30/11/2024

Comment posted: 30/11/2024

Jeffery Luhn on The Balkan Spomeniks – Monuments for a new tomorrow

Comment posted: 30/11/2024

Nice photos of interesting monuments that I knew nothing about. Cool!

Simon Foale on The Balkan Spomeniks – Monuments for a new tomorrow

Comment posted: 01/12/2024

Alexander Seidler on The Balkan Spomeniks – Monuments for a new tomorrow

Comment posted: 01/12/2024

Paul Quellin on The Balkan Spomeniks – Monuments for a new tomorrow

Comment posted: 03/12/2024