My photographic story’s a classic one, a cliché you might say. It all started when I was just 8 years old on the day my grandmother gave me my first camera, passed down to me from her mother.

It was a Kodak Instamatic — about as simple and fuss-free as you can get, and I remember feeling so excited by the new world opening up in front of me via that humble item. In those moments, I knew I wanted to be a photographer, so that’s what I became.

As I loaded each 126 film cassette — remember those? — I’d steadily get to grips with composing the scene through the parallax-riddled viewfinder before deciding whether or not the light levels warranted sunny, kinda sunny, white cloud or black cloud.

I had bucket loads to learn, of course, and a similar amount of pocket money to burn through (plus ça change) but I had spirit and ambition on my side, valuable traits that have never left me.

There was one crucial thing that I was learning without knowing it, though: how to make a photograph with limited means. Whether a landscape, close-up or portrait, I didn’t have a huge kitbag full of options. I just had my Instamatic and that was that.

Heading into my teenage years, I became lured by the glitz of gear. 35mm camera bodies and big lenses were particularly dazzling — anything that would make me look and feel like my perception of a pro.

I had worked my way through a flurry of hand-me-down Praktica bodies and lenses before spying a secondhand Nikon F3 HP in the window of my local London Camera Exchange — it even had the hallowed MD-4 motordrive bolted to the bottom!

My Dad snapped it up as a very generous 16th birthday present but he knew what it would mean to me. After all, I’d already been a photographer for 8 years and I’d done well in my GCSEs.

In my eyes, that camera was heavenly. The stuff of dreams. It served me well, too, and still sits on a bookshelf in my studio as a prized item, a memento of those early heady days of discovery.

Looking back at the period when I hankered after new pieces of equipment to bolster my arsenal, I had an awareness that I didn’t actually use much of it. More often than not, I found myself sticking to a 50mm prime lens or 35-70mm zoom.

The telephoto zooms would invariably stay in the bag and I’d feel strangely guilty about it. With a young head on my shoulders, I don’t think I’d worked out the simple reason behind it. However, fast forward (nearly) 30 years, I now feel very clear about the reasons.

You see, I wasn’t actually interested in the gear at all. I was interested in the story. In truth, I wanted to be as nimble as possible and reduce the equipment choices to a minimum so that I could simply get on with telling the story.

Like my spirit and ambition, and with an older head on my shoulders, I now realise that’s a facet of my working methods that has never left me either.

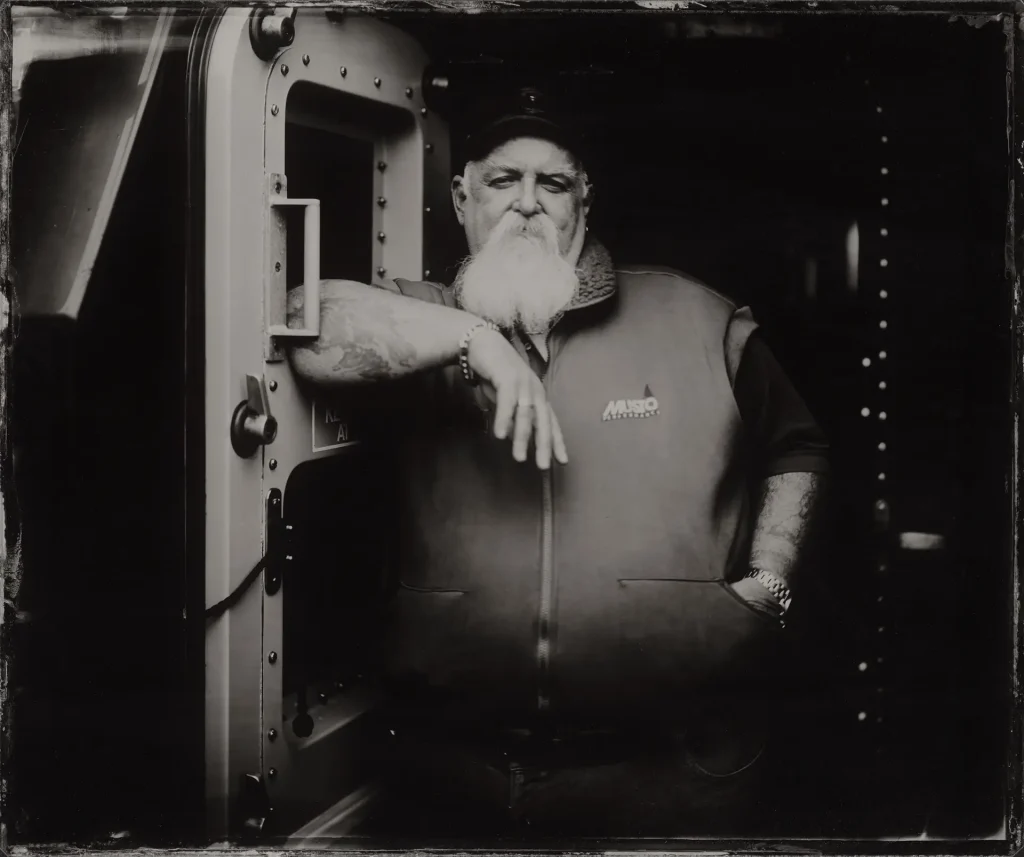

One camera, one lens — that’s all I’ve used to make some two thousand 12×10 inch glass plates on The Lifeboat Station Project over the last 5 years. Furthermore, it’s worth considering that the equipment is around 115 years old.

Have a scroll through the glass plates. Whether it’s a landscape or portrait, I’ve made everything work with the same camera and lens.

It’s a wonderfully simple discipline, one that frees the mind enabling me to see without being blinded by the kitbag. Moreover, in working with a streamlined inventory, you will see better too. You will become a better photographer.

I’d challenge anyone to try this, in fact I often suggest it during my talks to photographic clubs and societies: For a month at least, select one camera body and one lens — a prime not a zoom, of course! — and only use that kit. With the kit choices removed, I bet my bottom pound note that you’ll think more, look more, see better and, in turn, become an infinitely better photographer.

If the mood takes you, perhaps take it a step further: Travel several hundred miles to a special location with no more than the one camera body, one lens and a tripod. When you arrive, set up the equipment and make just one exposure. When you’ve done that, pack up and travel home.

If that sounds ridiculous, consider for a moment that it’s essentially how I’ve worked my way around the coast of the UK and Ireland for over five years. Nothing like a bit of jeopardy to focus the mind!

One camera, one lens, one month. It’s the perfect time to give it a go. Who knows, by the end of the month, you might never go back to your old ways. And if I’m wrong about you being a better photographer, feel free to keep that pound note!

If you’d like to learn more about The Lifeboat Station Project, head to the website where you can see all the photographs made so far, as well as listen to some of the audio recordings.

You can also sign up to receive the newsletter and learn about the many ways to become a supporter, including joining as a patron (as Hamish has done) from just £1 per month.

If you’d like to follow on social media, you can find me on Twitter.

See you there!

Thank you for reading,

Jack

Share this post:

Comments

Sciolist on One Camera, One Lens – A Methodology that Stuck – by Jack Lowe

Comment posted: 31/07/2020

Comment posted: 31/07/2020

Graham Spinks on One Camera, One Lens – A Methodology that Stuck – by Jack Lowe

Comment posted: 31/07/2020

Comment posted: 31/07/2020

Kevin Ortner on One Camera, One Lens – A Methodology that Stuck – by Jack Lowe

Comment posted: 31/07/2020

Comment posted: 31/07/2020

Markus Larjomaa on One Camera, One Lens – A Methodology that Stuck – by Jack Lowe

Comment posted: 01/08/2020

Comment posted: 01/08/2020

Daniel Castelli on One Camera, One Lens – A Methodology that Stuck – by Jack Lowe

Comment posted: 04/08/2020

I'm finally glad to "met" the photographer behind the lens (and film holder!) of the remarkable series of photos depicting the Life Boat Service. I read about your work and images in Black White Photography magazine. It's a great publication, the production values are second to none. It's the only photo mag I still get here in the US.

Your photos are remarkable, but they're more than what meets the eye. You've created photo artifacts; you've slowed down time and honor the subjects of your project by your working methods.

A few years ago, I shot an entire year with a 50mm lens mounted on my M2. My full kit included a Gossen (analog) Luna Pro, HP-5 film and anicillary bits and pieces. I can't say I fully enjoyed the self-imposed limitations, but I emerged understanding one thing; I 'see' with 35mm eyes, and since then I've pretty much stuck with the moderate wide-angle lens. That should be the point of such an exercise. It actually is liberating; you never second guess your lens selection. And, at my age (69) one could say the die is cast, and there isn't much time left to make major changes.

Finally, I'm awe struck by these remarkable volunteers who risk death on a regular basis Like the members of the international medical profession who have worked to create miracles during COVID-19, they truly deserve to be called heroes. Thank you for showing them to the world.

Keep healthy.

-Dan

flickr.com/photos/dcastelli9574/

Comment posted: 04/08/2020

Chris Rusbridge on One Camera, One Lens – A Methodology that Stuck – by Jack Lowe

Comment posted: 04/08/2020

Comment posted: 04/08/2020

Bernd Runde on One Camera, One Lens – A Methodology that Stuck – by Jack Lowe

Comment posted: 05/08/2020

-Bernhard (aka Cliff)

Comment posted: 05/08/2020

Soloman khan on One Camera, One Lens – A Methodology that Stuck – by Jack Lowe

Comment posted: 10/08/2020

Comment posted: 10/08/2020

Jack Lowe | Featured Photographer | On Landscape on One Camera, One Lens – A Methodology that Stuck – by Jack Lowe

Comment posted: 20/09/2020

Earl Goodson on One Camera, One Lens – A Methodology that Stuck – by Jack Lowe

Comment posted: 10/12/2020